Lower Rhine

Niederrheinisch is a comprehensive collective term for the dialects of the Lower Rhine . The Lower Franconian dialects originally spoken in today's administrative district of Düsseldorf are referred to as Niederrheinisch (or Niederrheinisches Platt) . These historical dialects are distinguished from the modern High German regiolects . The latter are referred to as "Lower Rhine German". The Lower Rhine dialects form (together with the West Munsterland dialect) both the smallest (geographical) and mostly heterogeneous (linguistic) clusters of the five main clusters within the German-speaking area.

Term Niederrhein

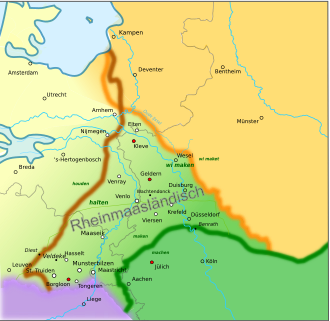

From a dialect point of view, the Lower Rhine refers to the region bordering the Netherlands in the west of North Rhine-Westphalia - for example between Emmerich / Kleve and Düsseldorf / Mönchengladbach / Heinsberg district - extending to the left and right of the Rhine.

The Lower Rhine region can best be described as the country whose inhabitants speak the Lower Franconian (Lower Rhine) dialects. Parts of the Lower Rhine overlap with today's Ruhr area , such as Duisburg, Oberhausen or Mülheim an der Ruhr, where, however, Lower Rhine-Lower Franconian dialects are also spoken. A "language wedge" also protrudes east of Düsseldorf into the Bergisches Land, so that the local dialects (the "Ostbergische") are also included in the Lower Rhine region. The region must be distinguished from the section of the Rhine , also known as the “Lower Rhine” , which begins further south-east at the mouth of the Sieg in the Ripuarian dialect .

history

Germanic tribes on the Lower Rhine formed in the 3rd century during the retreat of the Romans from the occupied part of Germania to one of the great tribes from which the Franks later emerged.

From the tribes that settled from the lower Lower Rhine to the Salland on the IJssel , the sub-tribe of the Salians , also called Salfranken , was formed. The tribes that settled from the greater Cologne area over the Middle Rhine to the Lahn were gradually absorbed into the Rhine Franconia and the Moselle Franconia descended from them . From the Lower Rhine, the Sal and Rhine Francs initially expanded spatially separated until they were united under the Merovingian Clovis I in the 5th century .

Franconian dialects

The Lower Franconian dialects in the Netherlands, Belgium and the German region of Lower Rhine (between Kleve and Düsseldorf) are traced back to dialects of Sal Franconian, with the southern Lower Franconian language area between the Uerdinger line and the Benrath line being considered the Lower Franconian-Ripuarian transition area.

The dialects spoken in the greater Cologne (Kölsch) / Bonn / Aachen ( Öcher Platt ) area are called Ripuarian . Together with the Moselle Franconian spoken in the Moselle region via Trier to Luxembourg, it is part of what is now called Middle Franconian . The dialects spoken further south in Hesse and Rhineland-Palatinate are known as Rheinfränkisch .

From "Frencisk" to "Diutisk" to "flat Duytsche"

The early Franks called their language "Frencisk" (or "Frencisg"). There are few written sources on the language of the early Franks. A Lower Franconian sentence from the Merovingian period comes from the Franconian popular law of the 6th century (the Latin Lex Salica ):

- maltho itho frio blito

- I say [,] I'll set you free [,] semi-free

- maltho friatho meotho

- I say [,] I set you free [,] servant

When the western part of the Franconian people (in what is now France and Wallonia) separated linguistically from the eastern part (in what is now the Benelux countries and Germany), conflicts arose with the name “Frencisk” ( Franconian ), because it is now an old French language speaking West Franconians claimed this term for their own "new" language. In the areas of what is now Germany and the Benelux countries, another term for the language prevailed: "Diutisk" ( German ). This term comes from an old Germanic term "Theodo" for people and appears in Latin scripts of the early Middle Ages as "theodisca lingua". Initially only referring to the “language” of the people, around the year 1000 the stem also got the meaning for the “people in themselves” - not only for the people of Franconian origin, but for all Germanic ethnic groups in the Franconian Empire. This also applied to Luxembourgers , Flemings and Dutch , who until the separation of the empire after the abdication of Emperor Charles V (1500 to 1558) also referred to themselves as “Germans” or “Low Germans” (see the term “Dutch” for “ Dutch ").

On the East Franconian (German) side there was a designation "Walhisc" ( Welsch , originally for a tribe of the Gauls) for the Gallo-Roman population in the West Franconian Empire, including the now Romanized West Franconia (see also Kauderwelsch and Rotwelsch ). On the West Franconian (French) side there was a distinction from the inhabitants of the East Franconian Empire to the name "Allemant" (for the Germans , derived from the Germanic tribe of the "Alamannen").

From the time of the linguistic separation of the (now French ) West Franks from the (now German / Dutch / Flemish ) Franks in the Eastern Empire, there is an important language testimony: the Strasbourg oaths of the year 842. They sealed the alliance between two grandchildren of Charlemagne ( Karl der Kahle and Ludwig the German ) against their brother Lothar. Because the entourage did not ( or no longer) understood the language of the other side, the oaths were taken in two languages - a forerunner of Old French (the language of Charles ) and Old Franconian (the language of Ludwig ). The old Franconian oath read:

- In godes minna ind in thes christanes folches ind our bedhero salary fon thesemo dage frammordes so fram so mir got geuuizci indi mahd furgibit so haldih thesan minan bruodher soso man with rehtu sinan bruodher scali in thiu thaz he mig no sama duo indi thing ne gango the minan uillon imo ce scadhen uuerdhen.

- Translation: For the love of God and the Christian people and our salvation, from this day on, as far as God gives me knowledge and ability, I will support my brother Karl, both in helping and in every other matter, just like his Brother should stand by so that he will do the same to me, and I will never make an agreement with Lothar that willingly harm my brother Karl.

A "famous" sentence is dated to the 12th century and is considered to be the most important Old Lower Franconian written document - Hebban olla vogala - an almost poetic rhyme:

- Hebban olla vogala nestas hagunnan hinase hic enda thu uuat unbidan uue nu

- Have all the birds started nests out, me and you, what do we not offer now

- Basically: Have all the birds started nests except me and you, what are we waiting for?

Rhine Maasland on the Lower Rhine

Only the written documents from the 14th to the 16th century are more understandable for today's readers. In the German-Dutch Rhine-Maas triangle, a written and chancellery language had developed that replaced Latin, which had previously been used primarily for written decrees: Rhine-Maasland .

Here is an example from this period, a "weather report" recorded in 1517 by the Duisburg Johanniterkaplan Johann Wassenberch:

- In the selven jair op den XVden (15th) dach yn April, end was doe des goedesdachs (Wodans day = Wednesday) nae Paischen (Passover, Paschah = Easter), van den goedesdach op den donredach (Donars day = Thursday) yn der night, wastz soe calt, dat alle vruchten van allen boemen, van eyckelen, van noethen, van kyrssen, van proemen (plums), van appelen etc. neyt uytgescheyden (nothing except) vervroren end verdorven (frozen and spoiled), want sy stoenden yn oeren voellen blomen (full bloom). Item (all the while) all the vynstocken froze up end withered, off (or) sy burned were. End (and) dair schach great ruinous pity.

The above excerpt shows a certain "closeness" of the "Rheinmaasland" to today's Dutch as well as to the Niederrheinischen Platt spoken on the German Lower Rhine.

In the 16th century, independent written languages developed in Germany and the Netherlands and Rheinmaasland lost its importance. For a longer period of time, German and Dutch coexisted in some cities (including Geldern, Kleve, Wesel, Krefeld, Duisburg) and decrees were issued in both written languages.

From the 18th century, the linguistic separation between the (German) Lower Rhine and the (Dutch) Maas area was finally completed. The respective high-level and written languages went their separate ways. Platt as the spoken dialect of the Lower Rhine has outlasted the new borders and has persisted into modern times.

Niederrheinisches Platt

The term Platt used in the north and west of Germany for one's own dialect is not derived from the fact that it is spoken in the “flat land”; rather, the Lower Franconian “plat” meant “flat”, but also something like “clear and distinct”.

In a Delft bible from 1524 there is talk of the "platten duytsche". In the Lower Rhine there are idioms to say something “flat vür dä Kopp” to someone (to say unequivocally to the face). Since there were also differences in the old Franconian language area between the “polished” expression of the upper classes and the “language of common vokes”, in this sense “speaking flatly” meant something like “speaking plain text”. Plain text that every farmer and craftsman understood. Thus, flat was the language of the common people.

structure

Individual dialects can be distinguished within the Lower Rhine region. The name "Niederfränkisch" for the dialects on the Lower Rhine is no longer used by the population themselves. The locals also rarely say that they speak “Niederrheinisch”, but rather “Platt” in connection with their place name.

Three large dialect areas on the Lower Rhine can be spatially delimited:

- North Lower Franconian (also called " Kleverländisch "):

- the Lower Rhine ( Kleve , Wesel ), in the Rhenish Ruhr area ( Duisburg ) - see Duisburg Platt , parts of Viersen (in Kempen ), in the northern district of sleeve of the city Krefeld - (see Hölsch Plott )

- South Lower Franconian (also called "Limburgisch"):

- in Mönchengladbach , the district of Viersen (with the exception of Kempen and northwest of it, where North Lower Franconian is spoken), Grefrather Platt in Grefrath ; then Heinsberg , as well as in the northern Rhine district of Neuss , in the district of Mettmann , in the greater part of Düsseldorf - see Düsseldorfer Platt , in Solingen , Remscheid and in Krefeld ( Krieewelsch ) - with the peculiarity that the northern district of Hüls beyond the Uerdinger line in North Lower Franconian lies. In Hüls one does not speak Krieewelsch, but Hölsch Plott and says z. B. ek or ec 'ich', in the rest of Krefeld esch or isch .

- in Mülheim an der Ruhr Mölmsch , Essen-Werden , Velbert-Langenberg and in the eastern parts of the old Duchy of Berg

Assignment

Northern Lower Franconian (Kleverländisch) and Ostbergisch can be clearly classified as Lower Franconian dialects. They are separated from the South Lower Franconian (Limburg) by the Uerdinger line . Due to their linguistic character, they are particularly close to Dutch . The Benrath line separates the southern Lower Franconian dialects from central German Ripuarian . They are therefore called transitional mouth species. The Ostberg dialects are spoken in Mülheim an der Ruhr, Velbert-Langenberg , Kettwig , Wuppertal - Elberfeld , Gummersbach and Bergneustadt . They are considered to be a transition dialect between Lower Franconian and Westphalian. The unit plural line weakening to the north serves as the border to the Westphalian . If the pronunciation intervals of the German dialects are considered, the Lower Rhine dialect area is geographically and numerically the smallest of the five clusters within Germany.

From dialect to regiolect

The Lower Rhine dialects of Lower Franconia , which differed greatly from the standard German language and were related to Dutch, were more and more displaced by High German after the Second World War, which experienced a special Lower Rhine characteristic.

Words and pronunciation peculiarities of the Middle Franconian (Ripuarian) dialects, to which the Cologne city dialect belongs, have penetrated the Lower Rhine dialect area over time, mainly due to the proximity to the city of Cologne and due to the high level of awareness of the Cologne dialect Groups like BAP , Brings , Höhner and Bläck Fööss .

Today Niederrheinisches Platt is only used as a colloquial language among older people in many places. The dialect is cultivated in associations and circles, it is taught in a few schools and on a voluntary basis.

In his book “Der Niederrhein und seine Deutsch”, the linguist and author Georg Cornelissen recorded the development that led more and more people from using the dialect to using the Lower Rhine German known as the Rheinischer Regiolekt . Hanns Dieter Hüsch , known as the “black sheep from the Lower Rhine”, has cultivated this “Lower Rhine German” in his plays and writings, even though he occasionally included “Grafschafter Platt” (the Moers dialect).

Typical for this Lower Rhine German is the use of certain sentence constructions that are reminiscent of Dutch, for example:

- It's about ... / it's about ... (Platt: et jeht sich dröm, dat ...)

- (Standard German: It's about ...)

- Who is that (Flat: wäm ös dat? Wäm hürt dat tu?)

- (Standard German: Who owns this? Whose business is it?)

The Lower Rhine German is also characterized by "simplifications" in pronunciation and "summarizing" words or word components to form new terms. The mix-up of “me and me” (and “you and you”) is also typical of the Lower Rhine region - this does not occur in “Cologne” Ripuarian. The “mix-up” is not a mistake for Plattspeakers, because the Niederrheinisches Platt only knows the standard form (like English and Dutch) - it would be wrong in standard German.

- he was with misch (instead of: he was with me)

- Platt: hä ös bej mesch jewäes

- she wrote me nisch (instead of: she did not write to me)

- Flat: Mech wouldn’t have yeschrieewe

Further examples of Regiolekt compared to Standard German and to Platt - whereby the sound level reproduced here corresponds roughly to Krefeld usage - it sounds a little different elsewhere on the Lower Rhine:

- Regiolekt: "Hate wat then bisse wat then can wat - look ma datte it will get you far!"

- (Typical Lower Rhine would also be: "... tumma (do) look datte with it, get far!")

- Standard German: "If you have something, then you are something, then you can do something - just see that you get far with it!"

- (In standard German it would be very inappropriate: "... just look ...")

- Platt: "Hate jet, then bad jet, then you can jet - kieck maar datte domöt how come!"

- (A platformer could also say: "... don maar ens kiecke ... / just look ...")

These examples show that the regional lecturer (who will never call himself such) orientates himself on the German standard language - but changes the words and the word combinations; in sentence structure and word order it largely follows the dialect. What cannot be seen in the above examples is the intonation (the "singsang") of the Regiolect, which subliminally follows the melody of the local dialect. The tone of voice in Kleve is different from that in Düsseldorf or Mönchengladbach. The more the Regiolekt speakers are informally "among themselves", the more pronounced the Regiolekt is used. If there are dialect speakers in the discussion, a mixture of regiolect and dialect will result. The more the speaker is in a "formal" environment or in a conversation with strangers, the less pronounced the Regiolect - Platt is avoided entirely, even if you could - and the Lower Rhine people involved in the conversation will use a language that they use even thinks of "cultivated High German" - Regiolekt or standard German.

See also

literature

- Georg Cornelissen : Small Lower Rhine Language History (1300-1900): a regional language history for the German-Dutch border area between Arnhem and Krefeld: met een Nederlandstalige inleiding . Stichting Historie Peel-Maas-Niersgebied, Geldern / Venray 2003, ISBN 90-807292-2-1 .

- Paul Eßer: Beyond the polluted willows. Language and literature on the Lower Rhine, Grupello Verlag, Düsseldorf 2002, ISBN 3-933749-83-2 .

- Kurt-Wilhelm Graf Laufs: Niederfränkisch-Niederrheinische grammar - for the country on the Rhine and Maas. Niederrheinisches Institut, Mönchengladbach, 1995, ISBN 3-9804360-1-2 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Introduction to Dialectology of German, by H. Niebaum, 2011, p. 98.

- ↑ Georg Cornelissen : The Lower Rhine and its German. Greven Verlag, Cologne 2007, ISBN 978-3-7743-0349-2 , pp. 11-14.

- ↑ Günther Drosdowski (Ed.): The dictionary of origin / Volume 7 - Etymology of the German language. Dudenverlag, Mannheim 1989, ISBN 3-411-20907-0 , p. 202.

- ↑ Erich Zöllner: History of the Franks up to the middle of the sixth century. CH Beck, Munich 1970, p. 109.

- ↑ Werner König: dtv-Atlas German language. Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-423-03025-9 , pp. 59-61.

- ^ Karl August Eckhardt (ed.): Lex Salica. Hahn, Hannover 1969, p. 76 (Lex salica, XXXVII § 1. and § 2.) and 235 (Glossary) ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica ; Leges; Leges nationum Germanicarum; 4, 2) ISBN 3-7752-5054-9 .

- ↑ Werner König: dtv-Atlas German language. Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-423-03025-9 , pp. 59-61.

- ↑ Werner König: dtv-Atlas German language. Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-423-03025-9 , pp. 59-61.

- ↑ Erwin Koller: On the vernacular of the Strasbourg oaths and their tradition. In: Rolf Bergmann, Heinrich Tiefenbach, Lothar Voetz (Ed.): Old High German. Volume 1. Winter, Heidelberg 1987, ISBN 3-533-03878-5 , pp. 828-838, EIDE.

- ↑ A. Quak, JM van der Horst: Inleiding Oudnederlands. Leuven 2002, ISBN 90-5867-207-7 .

- ↑ Irmgard Hantsche: Atlas for the history of the Lower Rhine. Series of publications of the Niederrhein Academy Volume 4, ISBN 3-89355-200-6 , p. 66.

- ↑ Georg Cornelissen: Little Lower Rhine Language History (1300 - 1900) , Verlag BOSS-Druck, Kleve, ISBN 90-807292-2-1 , p. 32.

- ^ Georg Cornelissen: Little Lower Rhine Language History (1300-1900 ) , Verlag BOSS-Druck, Kleve, ISBN 90-807292-2-1 , pp. 62-94.

- ↑ Irmgard Hantsche: Atlas for the history of the Lower Rhine , series of publications by the Niederrhein Academy Volume 4, ISBN 3-89355-200-6 , p. 66.

- ↑ Irmgard Hantsche: Atlas for the history of the Lower Rhine , series of publications by the Niederrhein Academy Volume 4, ISBN 3-89355-200-6 , p. 66.

- ↑ Dieter Heimböckel: Language and Literature on the Lower Rhine , Series of publications by the Niederrhein Academy Volume 3, ISBN 3-89355-185-9 , pp. 15–55.

- ↑ Georg Cornelissen: My grandma still speaks Platt. Greven Verlag, Cologne 2008, ISBN 978-3-7743-0417-8 , pp. 25-27.

- ↑ Georg Cornelissen: My grandma still speaks Platt. Greven Verlag, Cologne 2008, ISBN 978-3-7743-0417-8 , pp. 25-27.

- ↑ Georg Cornelissen: My grandma still speaks Platt. Greven Verlag, Cologne 2008, ISBN 978-3-7743-0417-8 , pp. 25-27.

- ↑ Hermann Niebaum, Jürgen Mache: Introduction to the Dialectology of German (= Germanist workbooks. Volume 37). De Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2011, p. 98.

- ↑ Introduction to Dialectology of German, by H. Niebaum, 2011, p. 98.

- ↑ Georg Cornelissen: The Lower Rhine and its German. Greven Verlag, Cologne 2007, ISBN 978-3-7743-0349-2 , p. 11 ff.

- ↑ Georg Cornelissen: The Lower Rhine and its German. Greven Verlag, Cologne 2007, ISBN 978-3-7743-0349-2 , p. 132.

- ↑ Georg Cornelissen: The Lower Rhine and its German. Greven Verlag, Cologne 2007, ISBN 978-3-7743-0349-2 , p. 126.