Norwegian monetary system

Norwegian Monetary System covers the history of money from the beginning to the end of the Scandinavian Coin Union (SMU) in 1924.

At the beginning of Norway's trading history is the currency of the goods. Some of it lasted until the 16th century. Certain goods had an (imperfect) monetary function . They were a means of payment and also a unit of account for comparing values, but had no store of value function. Such goods (natural produce) were essentially cows (cow value), butter, hides and grain. The term 'money' is the generic term for natural products and coins or paper money .

A distinction must be made between the sovereignty of coins, which determines the value, weight and appearance of the coin, and the subordinate right to mint , which only includes the production of the coins, sometimes also the right to determine the appearance of the coin. The archbishops of Nidaros had such a right to mint from 1222 to 1281 and from 1483 to 1537, Håkon Magnusson from 1284/1285 to 1299 when he was still a duke, and possibly Jarl Skule Bårdsson from 1217 to 1222. The indigenous coinage was under Harald Hardråde (reigned 1047-1066) Subject of state control and administration, which extended to the minting of coins and the determination of the monetary value. In Norway, commodity money and coins were used side by side for a long time.

Until 1873, the silver coinage was used in Norway.

The beginnings

Commodity money

It all started with goods money in Norway. It was not checked for quality and value by an authority. The relevant regulations were only guidelines as to which properties the commodity money had to have in order to be recognized at its full value. Since the goods were ultimately put to use even if they were exchanged several times, one cannot speak of goods in circulation.

“One should pay in grain and bulls and stable cows, as penances and rings. You have to pay in gold or burned silver in case of penance, if you have it. With horses. Not with mares, with a stallion and not with a gelding. With a horse whose bowel does not emerge, has a penis fungus or a weak bladder or a glass eye or other damage that makes it unsaleable. You can pay with sheep, but not with goats. You can pay with Odelsland, but not with purchased land. You can pay with a ship if it is not in need of repair or is so old that the first oarlocks are already worn out. Not even one with broken stems. Not even one with pieces of wood inserted, unless they have been inserted on the slipway. Nothing worth less than an Øre can be used to pay for. Unless the penance is less. Then he [the penitent] should accept the payment, unless the penance increases to an Øre. And he should accept a security deposit. One can also pay with a sword that is in use. Safe and hard. And unbroken. He must not offer the sword with which [the blow to be atoned] was wielded. Nor may one offer a sword that [only] counts as moveable property, unless it is decorated with gold. Or with silver. You can pay with Vadmal and with new linen. And with new uncut fabric. Unless he wants new cut fabric. You can only pay with fabrics for men's clothes, not those for women's clothes. New and not old. You can pay with new and uncut pelts. You can pay with black sheepskin and fine fabric. New and uncut. One can pay with servants who have been raised at home. With anyone not younger than 15 winters old, unless the other accepts him. In the case of penalties, one may not pay with maids. "

For the payment when redeeming an Odelsgut, the Gulathingslov prescribes:

"Half of the payment should be made in gold and silver, half in local slaves, no older than 40 winters, no younger than 15 winters."

In Frostathingslov, silver is set as the assessment basis for penalties under canon law.

Coinage

The coin finds are to be used as an archaeological source. For the period from 1000 to 1630 in Trondheim alone, around 1952 coins were found in excavations between 1843 and 2005.

In general, it was assumed in research that coins initially played no economic role in Norway. But this has been decidedly contradicted in the latest research.

The first known Norwegian coin was minted around 1000. It is a penny that is attributed to Olav Tryggvason (King 995–1000). But also his opponent, the archer jarl Erik Håkonsson , had his own coins minted. He felt that he was equal to the king in his domain.

Two square silver pennies from Olav the Saint (King 1015-1028) were also found. In chapter five of the Fóstbræðra saga, which takes place in the time of Olav, Sigrfljóð pours three hundred silver vermouth into the lap as a manslaughter. That doesn't seem to have been hacked silver; because it is not weighed and Vermund is satisfied. But final certainty cannot be gained, as it is said: “The silver was good”, which would hardly have been mentioned in the case of minted silver.

The Danish kings Sven Gabelbart and Canute the Great did not have any coins minted for Norway during their rule over Norway. No coins from them were found in Norway either.

Magnus the Good (King 1035-1047) had coins minted in Lund and Denmark. In 1047 there was a condominium with Harald Hardråde. After that, Harald continued his rule alone and over time deteriorated his coins up to the "Haraldslatten", a coin that only contained 50% or less silver.

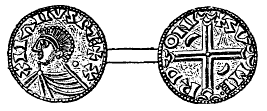

Coin from Magnus the Good .

For a long time, the penny was the only coin. In Erik Magnusson's time, one pfennig was worth 1 1 ⁄ 2 marks by weight of butter (= about 320 g) or 1 Ask (= 10.8 l) of lamp oil.

Coin as the state currency

There are three phases in the use of coins: Before 1060, almost exclusively foreign coins were found in the treasure trove. Between 1060 and 1320, almost exclusively Norwegian coins can be found. After 1320, the proportion of foreign coins continued to grow.

Coins of kings

When the throne was changed, the new ruler minted new coins and declared the previous coins to be invalid ( disreputable ) so that several different types of money were not in circulation. What was to be done with the old coins, whether and how they could be exchanged, is not known. But from the end of the 13th century, the sources dealing with monetary payments made more and more frequent mention of the fact that it must be circulating money (usualis monete; ganghs peningha). Nevertheless, the commodity money was still recognized. In 1303, for example, a piece of land in Bergen was sold for "nine Laup Butter or the equivalent amount in circulating money". The changing silver content of the coins was in some cases compensated for by sliding clauses. An ordinance of 1282 on the price of goods in Bergen states that all other goods should be paid for as it has always been, and so much less as the money is now better than before. The ordinance is puzzling, however, as the coins continued to deteriorate and is seen as confidence-building propaganda announcing a better currency.

Harald Hardråde

Harald Hardråde (king from 1047-1066) introduced the state coinage. He determined the right to mint as a royal privilege and shelf . He gave the coins a different appearance from the foreign and former Norwegian coins. For the weight of the coins the old Norwegian weight system Mark, Øre and Ertog was used. These were Triquetra coins, named after their stamped mark. The silver content varies between 96.7% and 16.0%. The treasure finds from the last decade of his reign already show around 60% Norwegian coins. It was a central concern of his monetary policy to exclude the foreign coins from the currency in order to secure control over the currency in order to get profit from his coin shelf. During this process, the silver content of his coins steadily decreased. He was the first in Scandinavia to use coin reduction as a source of income on a large scale. The Danish King Sven Estridsen followed him a short time later.

At the time of Harald and also with his successors, the currency was structured as follows:

1 Mark = 8 Øre = 24 Ertog = 240 Pfennig with an average weight of 0.88 g. Mark, Øre and Ertog were actually weight units. Since the silver coins were mixed with copper to varying degrees, a distinction must be made between money marks and weight marks (pure silver). This led to a conflict: In Frostathingslov it was stipulated that church fines were to be paid to the bishop in "silver", which was understood to be the silver coins common at the time. The silver content decreased steadily, which led to a noticeable decrease in church income. Archbishop Øystein now enforced that all penalties in his diocese should be measured in pure weighted silver, which led to an actual doubling. This provision was repealed under King Erik II .

While coins from Harald's time are provided with trial scratches, with which one ascertained the quality of the silver used, this custom ceased in the course of his reign, although the quality deteriorated. This is interpreted to mean that the silver content was no longer important later, so that the coin was no longer valued according to the silver value, but was recognized as a means of payment whose value was above the material value. These bad coins were called "Haraldslatten". The king ensured that the value of the coins remained the same as that of the old coins and, for example, paid out the wages in the same amount as before. Based on the preserved dies and their wear and tear, the number of coins minted under Harald is estimated at 500,000 coins.

The coins of kings Harald Hardråde and Olav Kyrre († 1093) were minted in Odense and transported to Norway. Foreign coins almost completely disappeared under Olav Kyrre. He also had coins with the silver content minted by Harald Hardråde. It is estimated that 2,500,000 coins were minted during its time.

The finds of the single coins from the 11th century are found in the context of craft and trade buildings, so that they are interpreted as a means of payment in local trade at the time of emerging urbanization.

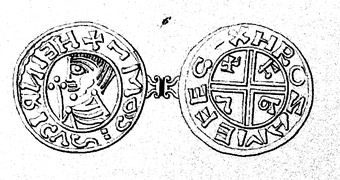

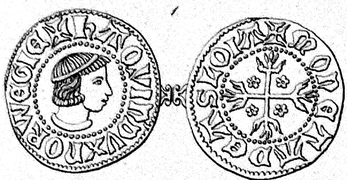

Penny coin from the condominium of Magnus the Good and Harald Hardråde.

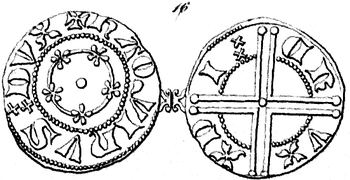

Triquetra coin by Harald hardråde .

Magnus Berrføtt and his sons

Magnus Bærrføt (King 1093–1103) carried out a coin reform, where he introduced half-heavy pennies (half pennies) with a high silver content, so that 480 pfennigs went to 1 mark. This measure is due to the growing resistance among the people to the bad coins of its predecessors. Halving the weight while maintaining the value was intended to secure the income he needed for his campaigns. The retention of the value could obviously not be maintained.

Under his sons, the kings Olav Magnusson (King 1103–1115), Øystein Magnusson (King from 1103–1123) and Sigurd Jórsalafari , bracteates were mainly produced because the blanks were so thin that only one-sided embossing was possible. The bracteates dominated Norwegian coinage until the end of the 13th century. Their weights were halved and quartered again so that half pennies and quarter pennies were minted. They were also usually underweight. It is no longer possible to determine what monetary value these bracteates actually had.

In the middle of the 11th century the territorial unification of Norway was complete, and a period of internal consolidation followed. A number of medieval state functions have their origins in the decades of transition from the Viking Age to the Norwegian Middle Ages .

Civil war time

Nothing is known about the monetary system during the civil war (first half of the 12th century). The coins of the first kings assigned to this time from the context of the find have no inscription that allows a clear assignment. The same applies to the coinage of the church. It was not until Magnus III. Erlingsson had coins minted that can be clearly assigned to him. The currency stabilized under King Sverre , who ultimately prevailed in the civil war. The coins consistently had a high silver content, but different weights for the same monetary value. A coin treasure from Vevey in Switzerland from around 1150, which was probably lost by a traveler to Rome, shows above-average weights for the Norwegian coin portion. This means that the population has withdrawn the heavier coins from circulation. A classic coin renewal like the one used by the earlier kings could not be implemented during a civil war. Therefore, many of the coins issued are very similar (only a few examples are shown here; there are countless similar variants of each coin shown). In the case of a coin renewal, the new coins must be clearly distinguishable from the invalid ones. Towards the end of King Sverre's reign, the silver content was halved without this being indicated in the appearance of the coin. Obviously King Sverre wanted to keep the value of the coin when the silver content was lower.

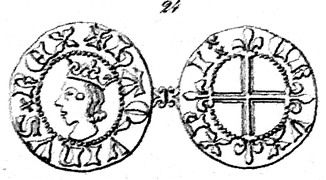

Coin from the time of Håkon III. Sverresons.

Time of the Bagler Wars

The first half of the 13th century was marked by the clashes between Birkebeiners and Baglers , the Bagler Wars. The coins had a high silver content, but were often produced as half-pennies or quarter-pennies. The quarter pfennigs in particular were extremely thin and unsightly, so that they weren't really suitable for circulation. In addition to the kings, the archbishops and Jarl Skule Bårdsson also had coins struck. But no clearly identifiable coins have survived. They can only be assigned to certain time periods based on the context of the find.

Bracteate from the time of King Inge Bårdsson

Quarter-penny bracteate from the time of Inges II. Or Håkon Håkonsson

Håkon Håkonsson and the bishops

Håkon Håkonsson (King 1217–1263) gave Archbishop Guttorm 1222 the coin rack for himself and his successors, in which the Archbishop could determine the silver content subject to the approval of the King. In doing so he legalized a practice that had apparently already been practiced. From this time and from Magnus lagabætir (King 1263–1280), Erik Magnusson (King 1280–1299. He revoked the archbishops' right to mint in 1281 in the dispute with Archbishop Jon Raude ) have survived. However, they cannot be clearly classified. Rather, the time of their production can only be inferred from the context of the find and from models from contemporary foreign countries. The coin with the lion can almost certainly be attributed to King Håkon, as he used the lion as a heraldic animal. According to Chapter 10 No. 13 (12) Frostathingslov of King Håkon Håkonsson, 18 Øre in coins corresponded to 12 Øre in silver weight.

More copper was now added again, so that 1 pfennig of pure silver corresponded to 3 courant pfennig.

Magnus lagabætir

A number of coins were struck under Magnus lagabætir , which can be clearly assigned to him on the basis of the text on them. The text on the reverse side “BENEDICTVS DE (us)” or “BENEDICT (um) SIT NOMEN D (omini)” is the Gros Tournois of Ludwig IX. borrowed from France, where the reverse text is "B (e) N (e) DICTV (m) SIT NOME (n) D (omi) NI N (ost) RI DEI IH (e) SV XP (Christ) I". Magnus changed the coins fundamentally by saying goodbye to the wafer-thin silver bracteates and by adding copper to mint heavy coins that were better suited for circulation. From a weight mark of this material 160 courant pennies were struck. The usual division of the weight mark was 240 weight pennies. The high amount of copper made the money unusable for external payments, so that Pope Nicholas III. In a letter to Archbishop Jon Raude von Nidaros from 1279, he refused to accept this money as a crusade tithing and asked him to buy goods at home that could be resold abroad. 1 penny by weight (0.893 g) of the coin material contained only 0.0625 g of pure silver = 70 ‰.

Counterfeiting was a problem even then. Magnus lagabætir felt compelled to enter into his land law chap. 4, 4, 2 to determine that no penalty was payable for killing a forger. Although there is no contemporary written evidence of a case of forgery, the discovery of Kalfarlien, a district of Bergen, with 1,800 exclusively counterfeit coins of the type that Erik Magnusson had issued between 1290 and around 1295 shows that forgeries were commonplace; because there are other finds of counterfeit coins from this time. Despite the findings of counterfeit coins, it can be assumed that the proportion of counterfeit coins in Norway was marginal.

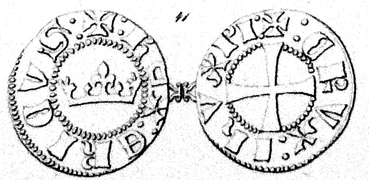

Erik II and Håkon V. Magnusson

Shortly after his accession to the throne, King Erik II (king from 1280–1299) stipulated that the coins of his predecessor Magnus lagabætir should remain in force. His successor Magnus Eriksson made the same determination before he became King of Sweden. The coins minted by Erik were therefore very similar to those of Magnus. But around 1285 he introduced a new coinage which, unlike the previous coins, did not have a king's head on the obverse, but the Norwegian heraldic lion with ax on a heraldic shield. On the back was a cross with four heraldic lilies in the four fields. They had the same standard of coinage and the same value. But they replaced the coins with the king's head in the treasure trove. The financing of his war against Denmark led to a further deterioration of the coin in 1290. These coins, called 'black crowns', were the coins with the lowest silver content in medieval Norwegian coin history. The population's trust in royal coins disappeared. In 1295, with the introduction of the Albi rosati , the silver content increased again.

During the reign of Erik II, his brother Håkon Magnusson was Duke of Norway. After Erik's death in 1299 he became King Håkon V. Erik had granted him the right to mint on the condition that he adhere to the same mint standard as the royal coins.

The first coinage under Håkons as king shows him with a crown, but in the legend it was forgotten to change the word DVX to REX. He immediately increased the silver content of the coins.

Magnus Eriksson and Håkon VI. Magnusson

So far, so few coins have been found from the time of King Magnus Eriksson that it cannot be decided whether they were minted in Norway or Sweden. The few treasure finds from this period contained exclusively foreign coins, usually sterling from England. This shows a weakening of the royal power towards foreign, especially the Hanseatic merchants. This influence of foreign merchants even led to the fact that the king himself used foreign currencies in his pricing legislation. There are written sources, sales contracts, lists of papal nuncios about tithing, and similar reports. The compilation of the collected Peterspfennig by Abbot Arnulv from the monastery Hovedøya near Oslo is informative. In it he reports the exchange rate for foreign coins and the ratio of the weight marks of pure silver to the current coin marks. After that, the coins had been renewed shortly before, and the previous copper coins were now worthless. These copper coins were called "Gunnarspenning", named after Gunnar Toraldeson, treasurer in Bergen, who proposed the reduction of the silver content to 1 ⁄ 5 of the weight of the coin and was approved by the king. Unfortunately Magnus Eriksson did not have his name immortalized on the coins, so that a clear assignment is impossible. After the personal union with Sweden in 1319, Swedish coins were also recognized as a means of payment in Norway, because the king, as the mint owner, guaranteed the coins that they were minted in Norway or Sweden. They were not foreign, but the king's coins.

Håkon VI. introduced new coins after the dissolution of the personal union with Sweden in 1363. They were bracteates with a crowned h . Around this time there was also a change in the use of coins: Up until now, coins have been weighed or used as a weighted unit of account, even if they may have been actually counted. In many regulations prior to the 14th century, information was given in both weighed and counted money. In the case of weighed money, the silver content mattered. After that they were just counted. Weighing was also required as there were no units indicated on the coins. The course of the counted coin compared to the weighed coin was determined depending on the silver content.

In the 13th century, Bergen developed into Norway's largest trading city. Foreign trade, especially in dried fish, increased by leaps and bounds. For this you needed foreign currencies. This included the local currency of the twin city for local purchases for daily needs and an internationally recognized currency for the actual wholesale business. These were the English sterling , in the 14th century also the English noble , the French turnose , the German witte , the Italian ducats , the florin and the guilder . These currencies were also used as a pure unit of account.

Summary of development

The development of coinage in the Middle Ages of Norway can be roughly described as follows: At the beginning of his reign, every king initially endeavored to issue coins that at least corresponded to the standard of his predecessor or, if possible, were more valuable. Since the coin represented the king, this was a means of making him appear as a good sovereign who looked after the well-being of his subjects. Neither Olav Kyrre, Erik Magnusson nor Håkon V. reduced the silver content of the coins at the beginning of their reign, but continued the standard of their predecessor. Magnus berrføtt, Håkon Håkonsson and Magnus lagabætir even began their reigns with a coin improvement. In the course of the reign, however, they did not maintain this attitude and worsened the standard of coins. This applies in particular to Harald Hardråde, Sverre Sigurdsson, Håkon Håkonsson, Erik Magnusson and Håkon V. Erik Magnusson is an exception, although he lowered the standard of coins to the notorious 'black crowns' because of his war, but did so at the end of his reign which Albi rosati regained the standard of its beginning. In general, the coin deteriorations run parallel to military campaigns.

End of Norwegian coin production

Norwegian coin production ended under Olav IV . This is attributed on the one hand to the economic aftermath of the plague , on the other hand to the lack of interest of the ruling dynasty of Folkung in Norway and, thirdly, to the general decline in silver deposits in Europe. This constant shortage of silver persisted until the Reformation. For the time after that, coins from Malmø and Germany can be found. The direct exchange of goods spread. Even the price regulations used natural produce. Travel reports from the beginning of the 15th century unanimously describe a coinless period in Norway. Only John I (King of Norway 1483–1513) apparently minted coins again.

Kalmar Union

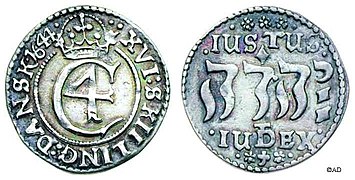

In 1458 Christian I confirmed the settlement of Tønsberg from 1277, which also renewed the archbishop's right to mint. Henrik Kalteisen , at that time still archbishop, was no longer in the country and therefore unable to make use of it. His successor probably did not make use of the privilege either. Coins are only known from Archbishop Gaute Ivarsson (term of office 1475–1510). Newly discovered silver deposits and the importation of silver from America to Europe made new coin production possible. The decisive turning point in Norway came under Christian IV, when silver deposits were discovered near Kongsberg in 1623.

In the electoral capitulation of King John I for Norway, which was made out on February 1, 1483 in Halmstad , it is stipulated that the duty to Sweden is to be paid exclusively in silver and that in Trondheim, in Bergen and in Oslo pfennigs after the Privilegium for the cathedral in Nidaros should be struck according to the needs of the empire, which had to be comparable with the Danish pfennigs. On this occasion, the Archbishop's right to mint was renewed.

Under King Johann and Archbishop Gaute Ivarsson, the Luebian coin system was adopted in 1513 and mainly Hvide = 4 Pfennig (German: Witten ) minted, as well as late medieval bracteates, which were called Hohlpfennig . In addition, a few shillings = 12 pfennigs and søslinge = 6 pennings (German: six of a kind ) came into circulation. Later the shillings dominated. Under Olav Engelbrektsson coins were even minted at 1 mark. In 1514 the Norwegian currency was assimilated to the Danish one. From then until the separation by the Peace of Kiel in 1814, both currencies were recognized as means of payment in both countries.

The word "mark" has two meanings: On the one hand, it is a unit of weight: It fluctuated from region to region between 186 and 280 g, but was mostly 219 g. After 1514 there was also the division into 16 Lodd (= Lot ) according to Cologne weight. This changed the weight of the Cologne mark to 214.4 g. This unit was in use until 1683. After that the Danish weight system was introduced and the weight mark was 1 ⁄ 4 kg. The measure of value was pure silver (Mark brent sølv or Mark rent sølv = 900–950 ‰). On the other hand, the mark denotes a unit of currency. Originally, the currency mark was supposed to contain one mark of fine silver, but in the Lübeck coin calculation, which included the Cologne weight unit for one mark of weight = 16 Lodd = 64 Kvintin. The Cologne weight mark in the 16th century was 233.85 g, 1 Lodd = 14.6 g, 1 Kvintin = 3.65 g and 1 Ort = 0.91 g. By reducing the silver content to 13: 1, 13 Luebian money marks had one Cologne weight mark of fine silver. The most common coins were pfennig, double-pfennig (Blaffert), three-pfennig (sterling or English), four-pfennig (Hvid), six-pfennig (half-schilling or Søsling), nine-pfennig (gros) and twelve-pfennig (shilling).

- 1 Rigsdaler = 3 Marks = 48 Schillings = 144 Hvide.

- 1 mark = 16 shillings = 48 hvides = 192 pennings.

Personal union with Denmark

During the personal union with Denmark (1521-1814), Danish coins were in circulation in Norway. But coins were also minted in Norway. From the time of King John I after the end of the Kalmar Union, when he was only king of Denmark and Norway (1501–1513), a shilling is known that was minted in Bergen . In addition, the Hvide was minted there during his reign.

During Christian II's attempt to retake Norway in 1532, many crisis coins, Klippinge, were struck up to 2 marks.

Christian III

Christian III, too . (1536–1559) issued coins in Norway. These were shillings, eight-shilling coins and 1 mark. In 1546 the Joachimstaler was added as silver guilders. The Daler was introduced into Denmark-Norway by decree of September 20, 1541. The values given on the thaler coin base were marks, 8 shillings, 4 shillings, shilling and hvide. The penny was excluded. In 1544 a mint was built in the former women's convent Gimsø near Skien , which obtained the silver from the recently opened Guldnæs mine in Telemarken . But the production facility burned down as early as 1546. Since the silver production was not worthwhile, the production was stopped and the silver sent to the mint in Copenhagen.

In 1546, coin production in Norway was interrupted for 28 years and only resumed by Frederick II (King 1559–1588) in 1574 , but stopped again between 1578 and 1628.

In the period between 1588 and 1625, coins were minted only in Denmark and Sweden, and then also circulated in Norway. This period was characterized by two factors: on the one hand, the increasing number of shillings for one thaler from 64 schillings to 96 schillings, which was mainly due to the importation of bad foreign small coins, and on the other hand, the minting of bad marks, later crowns that were issued at a higher special thaler value than the silver content justified. In the end, the Rigsdaler was set at 96 Schillings and the Krone at 2 ⁄ 3 Riksdaler.

The new mint

In 1628 Christian IV founded a mint in Christiania, today's Oslo . It was in Akershus Castle . She used silver from the mines and works in Kongsberg , which were built in 1624. In 1625 a new coinage order was issued, which set the value of the speciedaler anew. This ordinance was decisive until 1813. There were 2-speciedaler, speciedaler, ½-speciedaler, ¼-speciedaler and ⅛-speciedaler minted. The values were set as follows:

- 1 thaler = 6 money marks = 96 shillings

- 1 crown = 4 money marks = 64 shillings

- 1 money mark = 16 shillings

On April 28, 1628, when the mint master was appointed, it was determined that he should strike talers from “Brent Sølv” (90–95% silver) (see Blicksilber ) from the silver of the mine . Each weight mark of pure silver (fine silver) should contain 15 lod and 2 quintin = 15 ½ lod of pure silver. For each weight mark, 9 thalers or 18 half thalers or 36 Ortsdaler (= 1 ⁄ 4 Taler) or 72 half Ortsdaler should be struck. Although the production of fine silver was already quite possible, “Brent Sølv” was set at 15 ½ lod and thus “Brent Sølv” was identified with fine silver (over 95%). The gross weight of the specie was thus equal to the net weight of the rich thaler with 25,984 grams of fine silver. At that time, fine silver was only one unit of account: 1 weight mark of fine silver = 16 lodges. The net silver weight of a specie was therefore 1 ⁄ 9 weight marks “Brent Sølv”, i.e. only 25.172 g of fine silver. Therefore, these thalers of the king were not recognized when the lower net weight of fine silver was recognized. At the same time, the gross weight of the Specie, at 25.984 g, was lower than the usual thaler at 29.232 g.

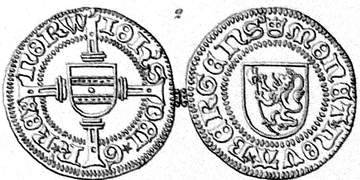

Speciedaler from 1628.

The Torstensson War in 1644 brought with it the issue of poorer war coins in order to finance the war. In addition, he took the Dutch thalers and the English silver crowns acquired through trading with Holland and melted them with additions to the poorer 2 money mark and 16 shilling pieces. These mintings were discontinued in 1647 and coins with a higher silver content were minted again under Frederick II, which were equivalent in value to Sweden's half-crown. In 1665 crowns and gold ducats were minted in addition to speciedalers. Queen Sophie Amalie's apanage of 12,000 Rigsdalers strained the mint in Kristiania to the limit of its capabilities. In 1665 they were paid out in 9,970 Rigsdalers in Specie, 150 Rigsdalers in Ducats and 1,880 Rigsdalers in Silver Crowns. In the years from 1668 onwards, one and two shilling coins were produced. The same coins minted in Copenhagen were lighter than those from Kristiania. It stayed like that for 20 years.

In 1670 Christian V ascended the Danish-Norwegian throne. Coin production continued as before.

Four marks from Christian V from 1671.

On March 31, 1686, the royal mint moved to Kongsberg , where it is still today under the name "Det Norske Myntverket" on Nybrofoss, and Henning Christopher Meyer became mint master. The mint in Kristiania remained. On January 16, 1687, Peter Grüner leased the mint. From 1686 to 1688 coins of 1, 2 and 4 marks were minted there. In 1695 the mint in Kristiania was closed and Grüner ended his activity in Kongsberg. "Det Norske Myntverket" was initially subordinate to the Ministry of Finance , since 1962 it has been subordinate to the "Norges Bank". “Speciedaler” and “Skilling” were coined. Coin production varied widely, in some years no coins were minted at all. The silver mine, the silver smelter and the mint had a common management, and the workers of the silver works were also employed in the mint. In addition to this mint, the kingdom of Denmark-Norway had coins minted in Copenhagen and Glückstadt. 1726 came under Christian VI. the 8-shilling coin, which was used to pay the miners in Kongsberg, and in 1734 the Rigsort, a 24-shilling coin that became the most widely used coin for a long time. Gradually, however, the technical problems increased in Kongsberg, apparently because the workers were insufficiently trained. Most of the coins were underweight, and in 1776 the die press broke into three pieces. Some of the dies were badly engraved, so they had to be re-manufactured in Copenhagen. In 1736, bank bonds on paper, the forerunner of paper money, appeared alongside coins.

In 1771 people tried to mint 1-Schilling copper coins, as they were already minted in Copenhagen and Altona . But not enough copper could be supplied from Copenhagen, so copper plates had to be obtained from Sweden. Then new equipment had to be procured. In addition, there was not enough staff, so production could not start until 1784.

Both Christian IV and Christian VII had piasters minted for the East India trade based on the Spanish model , Christian IV in Copenhagen, Christian VII also in Kongsberg. He had 1, ½, 2 ⁄ 3 , 1 ⁄ 5 and 1 ⁄ 15 speciedaler as well as 1, 2, 4, 8 and 24 schilling coins minted in Kongsberg .

The paper money had stepped aside the minted money.

In 1807 Copenhagen was bombed by the English navy. All ships in the port of Copenhagen were then brought to England as booty. There was also an effective sea blockade. Trading became almost impossible, resulting in a 152% rise in prices and hyperinflation in which money lost 60% of its value. By the end of 1812, the paper courant had lost 95% of its value. 1 760 Rigsdaler courant had to be paid for 100 silver special thalers.

In 1814 Norway was split off from Denmark in the Peace of Kiel and came under the Swedish Crown as an independent empire. The Norwegian state budget and currency remained divorced from Sweden. In 1816 the Norwegian currency was reorganized. The Rigsbankdaler , which had been common up until then , was replaced by the Speciedaler. A Cologne weight Mark fine silver came 9 1 / 4 Norwegian Speciedaler that in à 5 Rigsort or money market 24 Schilling were divided. Whole, half, fifth and fifteenth speciedaler, which were later exchanged for tenth speciedaler, were minted.

The bank bonds

Initially, bank bonds were issued.

The first banknotes were introduced in Norway in 1695. That was very early. Only Sweden and Great Britain had issued paper money earlier. King Christian V had allowed his friend, the merchant and shipowner Jørgen Thormølen from Bergen to issue bank notes that were to be valid from the southern tip of “Sønnafjelske Norge” in Åna-Sira to the north along the entire coast. In doing so, he supported Thormøhlen, who had run into a liquidity crisis while doing business in St. Thomas . They should be redeemed in coins after five years. But since nobody actually accepted these notes, Thormølen went bankrupt.

The bank as a state financial institution

The first central bank was founded in 1736 under the name “Den Københavnske Assignations-, Vexel- og Laanebanken”, also known as “Courantbanken” (after the currency “Rigsdaler Dansk Courant”). It was a stock company for which the king issued regulations. In addition to issuing banknotes with the silver cover valid at the time, it granted the state loans. Since no upper limit had been set for the issuance of banknotes, soon more banknotes were issued than silver coins were available for redemption. In 1745 she had to stop the redemption. As a result, the notes lost a large part of their value. In 1757 the obligation to pay was legally repealed and only reintroduced in 1842. In 1760 it became necessary to increase the share capital from 500,000 Reichstalers to 3,000,000 Reichstaler. In 1773 the state took over the bank to finance its budget.

In 1791 a new bank was founded to reorganize the monetary system, "Den Danske og Norske Speciebank". It had three branches in Norway. But again more banknotes were printed in Copenhagen than silver coins were available. But things looked different in Norway. Bernt Anker found that there were 30,000 Rigsdaler in circulation in Christiania, compared to a material value of 1,000,000 Rigsdaler. He therefore pleaded for an expansion of the money supply and for the establishment of a Norwegian bank through which the timber export should be handled. In 1799 "Deposito-Cassen" was founded.

- Before 1813, the old Danish-Norwegian monetary unit "Rigsdaler courant" (= 80% Rigsdaler specie) was in force in Norway.

- In 1813 the government in Copenhagen introduced the " Rigsbankdaler ". The exchange ratio was set at 6: 1, so for six old Rigsdaler courant (as a paper bank order) one received a Rigsbankdaler note.

- In 1816 the Storting passed the Norwegian Bank and Monetary Act. The monetary unit "Speciedaler" was introduced as a bank transfer on paper. The exchange ratio was 10: 1, for ten old Rigsbankdaler you received a special thaler as a bank order.

The new beginning

As a result of the Peace of Kiel in 1814, Norway was forced into a personal union with Sweden, but retained the right to regulate its own internal affairs. In addition, the state coffers remained separate. From the period from 1807 to 1809, so-called “Assignation Sedler” and Reichsbanknotes of the Danish-Norwegian Reichsbank in the amount of 5,139,000 Riksbankdaler were in circulation. In addition, there were 3,000,000 Riksbankdaler that Prince Regent Christian Friedrich had issued in Norway at the beginning of 1814. This entire paper money and the other paper money that was required for the budgeted government expenditure and was estimated at 14 million Riksbankdalers, plus the Danish Riksdalers, which were still permitted as a means of payment, which were converted into Riksbankdalers in the course of 1814, led to the fact that in the course of In 1815 there were around 23 to 25 million Riksbankdaler notes in circulation. This led to inflation. The full oath guarantee should stabilize the monetary value. But the rate continued to fall, so that 1 Riksbankdaler, which according to the full oath guarantee should have a value of 32 Norwegian silver skillings, had dropped to 6 skillings in January 1816. The national bankruptcy had occurred because the bank bonds issued could no longer be redeemed in the guaranteed silver coins. The full oath guarantee was canceled in January. The paper currency was thus created by being exempted from the obligation to redeem it in silver and circulating independently as money.

At first they wanted to set up a Norwegian bank through voluntary subscription of shares. But the trust was so low that a compulsory silver tax had to be levied in order to receive the required two million speciedaler start-up capital. In 1816, two years after Denmark separated from the union with Sweden, Norges Bank was founded. It did not take up its function until 1818. For the paper money that has now been issued, the obligation to redeem it in coins has been postponed. In addition, an oppressive tax was levied to finance the new state. Part of the state budget was also financed by expensive government loans abroad. This restricted the need to print paper money for it. When Finance Minister Count Wedel-Jarlsberg ensured that everyone could pay their silver tax with old paper Rigsbankdalers at a rate of 25: 1 speciedaler, the rate soon stabilized at the previous level of 10: 1. In 1822 the Norwegian Bank began the strategy of gradually arriving at a par rate, that is, 100 special talers could be obtained for 100 special talers. This goal was not achieved until 1842. The law of April 29, 1842 reintroduced the bank's obligation to redeem paper money in silver coins of the same nominal value.

Before 1873, Scandinavian coins circulated within this area. One Norwegian speciedaler was two Danish Rigsdaler and four Swedish Riksdaler. The four Swedish riksdalers contained 25.5044 g of pure silver, the Norwegian speciedaler 25.2996 g and the two Danish Rigsdalers contained 25.2816 g. This led to a continued outflow of money from the Swedish central bank. In addition, the gold standard had prevailed in the non-Scandinavian mainland, so that the coins with the silver standard were no longer freely convertible. All of this led to the introduction of the gold standard and the metric coin system.

By law of June 4, 1873, the Storting decided that the terms crown and Øre could be used in parallel with thaler and daler . The established Nordic Coin Commission proposed the introduction of the gold standard. 10 and 20 gold crowns should be made from 90% gold and 10% copper. One kilo of pure gold was supposed to produce 124 pieces of 20 kroner coins or 248 10 kroner coins. The crown was divided into 100 Øre. "Øre" was an old Scandinavian coin name. The term "crown" was first used for the gold coin of Frederick II. It was not until Christian IV. Also called silver coins “crown”. The reason was the imprinted royal crown. While Denmark accepted this currency reform with a law of January 23, 1873, the Norwegian Storting initially rejected the currency reform. It was not until October 16, 1875 that Norway joined the Union of Coins. In the meantime, gold coins with denominations of crown and specie were minted.

The exchange ratio between gold and silver was 1: 15.5 and the currency ratio was 10 Swedish riksdalers = 1 gold ten-kroner piece, i.e. 1 Swedish riksdaler = 1 krone, 1 Danish rigsdaler = 2 kroner.

This enabled Norway to join the Scandinavian Coin Union. In 1875 it was decided that the krona would become the unit of currency in Norway, so that Norway could join the Scandinavian Coin Union on October 16, 1875 . During the First World War , the export of gold and silver was banned. During this time, the volume of the notes quadrupled. The crown was still valued. Inflation and a high volume of imports led to a crisis in 1920 and reduced confidence in the krona. On September 27, 1931, the gold standard was abolished. Norway and the other Nordic countries were determined to prevent harmful fluctuations. In 1945 a currency reform was carried out to prevent inflation. On May 24, 1985, a new Norges Bank and Monetary Act came into force (Central Bank Lov). The bank was no longer a limited liability company (GmbH), but became an independent legal entity owned by the state. On May 5, 1994 a guideline for the fluctuating krona exchange rates was drawn up. In 1998, the first complete replacement of a coin series since 1875 was completed. The law on payment systems came into force in 2000. The law regulates the responsibilities of Norges Bank and monitors the payment systems. In 2001 the new regulation on monetary policy was passed by the State Council.

Europe, 1872

The Scandinavian countries Sweden , Norway and Denmark were forced to change their currency policy as soon as possible , as their most important trading partners had a so-called gold standard. Germany had had the uniform gold mark since 1871, the successful gold sovereign had been circulating in Great Britain for a long time, and in most other southern and eastern European countries gold and silver coins have been minted according to the standards of the Latin Monetary Union (LMU) since 1865 . Without a single, secure currency, Scandinavia would be economically sidelined. Each country sets the value of its currency to gold in a so-called gold standard. Paper money can therefore be completely exchanged for gold at the central banks, since the value of the money is directly linked to the value of the gold. As it is today, gold was worth the same all over the world. Thus international capital transactions were possible through the gold standard. The gold standard has been in existence as the basis for international currency matters since 1870. Previous differences between the value of gold and silver were eliminated with the establishment of the Latin Monetary Union in 1865. This introduced a fixed exchange ratio between gold and silver coins.

As early as 1862, Norway, Sweden and Denmark had been in negotiations about measures in the monetary system and about rapprochement with foreign currency systems. For Sweden the negotiations took too long. That's why they wanted to join the LMU. Between 1868 and 1872, Sweden minted gold coins with a face value of 10 francs or 1 carolin according to the guidelines of the LMU. Today this coin is in great demand as only around 81,000 copies were minted in a period of 5 years. The introduction of the gold standard in 1871 in the German Empire was the decisive factor for the final establishment of the Scandinavian Coin Union (SMU). On December 18, 1872, the founding contract for the SMU, also known as the Nordic Mint Association, was signed. At this point in time, the three Scandinavian states had not yet agreed on the treaty points. However, Norway only introduced an additional convention into the treaty in 1877 . Norway wanted to demonstrate a piece of independence from Sweden. Sweden was linked to Norway in a personal union since 1814 . Norway minted gold coins according to the standards of the SMU as early as 1874. These were minted with a double value in both crowns and “speciestaler”. Speciestaler was the currency in Norway since 1816.

Iceland , which had been in Danish possession since 1380 , also belonged to the Scandinavian Coin Union . It only became an independent kingdom in 1918 and introduced its first own coins from 1922.

The joint introduction of a gold currency with a decimal system was justified by the Union Treaty. The only difference between the coins is the national coinage. From then on, the Danish, Swedish and Norwegian kroner (Kroner) were swapped 1: 1: 1. There were three different gold coins for 5, 10 and 20 crowns as part of the SMU.

After the Scandinavian adaptation in 1879, Japan and the USA , 1892 Austria , 1897 Russia and 1900 other countries such as Argentina , Peru and Mexico adopted the gold standard for their currencies .

Already during the First World War from 1914 to 1918 there was exploitation of exchange rate differences between the individual countries. Norwegian and Danish banknotes flowed into Sweden. There they could be exchanged for gold at a profit. Since this imbalance in the flow of money could not go well in the long term, foreign coins were abolished as legal tender within a country of the SMU in 1924. This meant the de facto end of the SMU. However, the gold standard continued to exist until it was repealed in 1931 in favor of the introduction of a paper currency. The Scandinavian Coin Union, in which 13 different gold coin types from the three participating states were minted, existed for almost 50 years.

After the dissolution of the monetary union, all three countries decided to keep the "crown" as the name of their respective, now independent, national currencies.

literature

- Øyvind Eitrheim: Fra kaos til stabilitet i pengevesenet i norge etter napoleonskrigene

- Øyvind Eitrheim: Fra Peder Anker til stabilitet i pengevesenet. In: Øyvind Eitrheim, Jan F. Qvigstad (ed.): Tilbakeblikk på norsk pengehistorie. Conference June 7, 2005 at Bogstad gård. Oslo 2005, pp. 1-17.

- Svein H. Gullbekk: Pengevesenets Fremvekst og Fall i Norge i middelalderen. Copenhagen 2009.

- Hans Holst: Norges mynter til slutten av 16. århundrede. In: Nordisk culture. 29: Mønt, Stockholm 1936, pp. 93-138.

- Jon Petter Holter: Historisk produksjon and omløp of mynt from the congregational mynt. (PDF; 545 kB) In: Penger og kredit. 2000 No. 3.

- D. Isaachsen: Norge. Mønt, Maal and Vægt . In: Christian Blangstrup (Ed.): Salmonsens Konversationsleksikon . 2nd Edition. tape 18 : Nordlandsbaad – Perleøerne . JH Schultz Forlag, Copenhagen 1924, p. 122-124 (Danish, runeberg.org ).

- Brita Malmer: A contribution to the numismatic history of Norway during the eleventh century. Commentationes de nummis saeculorum IX-XI in Suecia repertis. Stockholm 1961, pp. 223-376.

- Jon Anders Risvaag: Mynt og by . Myntens roll in Trondheim by i periods approx. 1000–1630, belyst gjennom myntfunn og utmynting. Trondheim 2006.

- N. Rygg: Norges Banks history. First part. Kristiania. (1918)

- CI Schive: Norges Mynter i Middelalderen. Christiania 1865.

- Kolbjørn Skaare: Coins and Coinage in Viking-Age Norway. The establishment of a national coinage in Norway in the XI century. 1976.

- Kolbjørn Skaare: Norges Mynthistory. 2 volumes. Oslo 1995.

- P. Volz: Royal coinage sovereignty and coinage privilege in the Carolingian Empire and the development in the Saxon and Frankish times. I. The Carolingian period. In: Yearbook for Numismatics and Monetary History. Volume 21, Hamburg, pp. 157-186.

- Julius Wilcke: Møntvæsenet under Christian IV and Frederik III 1625-1670 . Copenhagen 1924.

- Julius Wilcke: Mønten paa Kongsberg. In: Julius Wilcke: Kurantmønten 1726–1788. Copenhagen 1927.

- Jacob Woxen: Møntfod. I Norge . In: Christian Blangstrup (Ed.): Salmonsens Konversationsleksikon . 2nd Edition. tape 17 : Mielck – Nordland . JH Schultz Forlag, Copenhagen 1924, p. 587-588 (Danish, runeberg.org ).

Individual evidence and explanations

- ↑ Risvaag p. 199 f.

- ↑ Gullbekk 2009, p. 22.

- ^ Gulathingslov § 223.

- ^ Gulathingslov § 266.

- ↑ Frostathingslov III, 2.

- ↑ Risvaag p. 14.

- ↑ So on the official website of Norges Bank in the section Norges Bank historie (English version History )

- ↑ So Svein H. Gullbekk on p. 374 of his unpublished doctoral thesis Pengevesenets Fremdvekst og fall i Norge i middelalderen . 2003, quoted in Risvaag p. 12: “... because the royal power was able to draw ever larger bills of exchange on the money-based relationships of society. The coinage and monetary system was an important tool of the royal power in the government and in state development. ”In her work, Risvaag discusses the more recent publications on Scandinavian coin finds and their interpretation in the section“ publikasjoner ”p. 52 ff.

- ↑ a b Hans Holst.

- ↑ Gullbekk 2009, p. 238 ff.

- ↑ Gullbekk 2009, p. 45.

- ↑ In the Diplomatarium Norwegicum vol. 1 no. 336 there is an account of the papal tithe handed over to the papal nuncio from 1353. There are listed "19 Marks in old abolished coins, for which no value can be set." A similar statement can be found in a receipt from the Nuncio to the Bishop of Stavanger from 1364 in the Diplomatarium Norvegicum vol. 4 no. 446.

- ↑ Gullbekk 2009, p. 61.

- ↑ Diplomatarium Norwegicum Vol. 1 No. 68.

- ↑ a b Gullbekk 2009, p. 131.

- ↑ Gullbekk 2009, p. 29.

- ↑ Gullbekk 2009, p. 32.

- ↑ Gullbekk 2009, p. 30.

- ↑ Harald Hardrådes saga in the version by Morginskinna: “When the eighth day of Christmas came, the men were paid their wages. This was called 'Haraldsschlag' (Harallz slatta). It was mostly made of copper. At best, half was silver. "

- ↑ After the Frostathingslov X.35 , 30 pennings = 1 Øre. ( s: no: Side: Norges gamle Love indtil 1387 Bd. 1 225.jpg ).

- ↑ Knut Helle in: Under Kirke og Kongemagt 1130-1350 . Oslo 1995, pp. 35, 207; Gullbekk p. 111.

- ↑ Gullbekk 2009, p. 40.

- ↑ In the Harald Hardrådes saga in the version of Morkinnskinna it is described that the Icelander Halldórr Snorrason refuses to go into battle with him because he does not accept the coins containing copper, so that the king finally pays with good silver. Morkinnskinna, 149-151, quoted in Risvaag, p. 194. But the other comrades-in-arms were paid the same amount with the bad coins. Gullbekk 2009, p. 132.

- ↑ a b Gullbekk 2009, p. 244 ff.

- ↑ Risvaag p. 133 f.

- ↑ Gullbekk 2009, p. 132.

- ↑ Gullbekk 2009, p. 67; Schive p. 39 f.

- ↑ Gullbekk 2009, p. 70.

- ↑ Diplomatarium Norvegicum III No. 1. It can be seen from an exchange of letters between Archbishop Pål Bårdsson and the Bishop of Bergen Håkon Erlingsson that the two agreed to reduce the silver content from 1 ⁄ 4 to 1 ⁄ 5, subject to the approval of the king . Diplomatarium Norvegicum VIII No. 128.

- ↑ Risvaag p. 141.

- ↑ Diplomatarium Norwegicum Vol. 2 No. 67.

- ↑ Schive p. 72.

- ↑ Gullbekk 2009, p. 56 f.

- ↑ Gullbekk 2009, p. 87 f.

- ↑ A contract between Mrs. Katharina Ivarsdatter and the bishop Arne von Bergen from 1306 stipulates that she should have free food and accommodation on the bishopric. For this he should receive 20 Månedsmatsbol from an estate belonging to her and other things more. He should reimburse her for any overpayment "in English money, butter or previously named goods, but Norwegian money or other goods not previously named may not be used for payment." Diplomatarium Norvegicum Vol. 2 No. 82.

- ↑ Gullbekk 2009, p. 168.

- ↑ Gullbekk 2009, p. 97.

- ↑ Gullbekk 2009, p. 165.

- ↑ Gullbekk 2009, p. 189 ff.

- ↑ Gullbekk 2009, p. 145 f.

- ↑ " La quarte monnoie voullent les seigneurs quant ont guerre, et peut donc a fair monnoie tant foible comme il veult pour avoir a despende et al paier a sa gent pour deffendre soi et sa terre. Corn a la fin de sa guerre, doit recouvrer la dicte monnoie. »(Guillome le Soterel, treasurer in Navarra around 1340 quoted in: Béatrice Leroy: Théorie monétaire et extraction minière en Navarre vers 1340. In: Revue Numismatique , 6th series XIV, 1972, p. 110., German:“ The fourth art money goes to the princes when they are at war, so they can spend as bad coins as they want to pay the soldiers to defend him, his people and his country. But when the war is over, he has to withdraw this money. ")

- ↑ Risvaag p. 308 f.

- ↑ Gullbekk 2009, p. 178.

- ↑ Gullbekk 2009, p. 179.

- ↑ Gullbekk 2009, p. 181.

- ↑ Kong Hans's norske og danske håndfestning (Halmstadrecessen) . In: Grethe Authén Blom (ed.): Norges gamle Love, Anden Rekke, 1388–1604. Volume 3 (1483-1513) I. Oslo 1966, pp. 3-35, 17, nos. 13 and 14.

- ↑ a b "Hvide" was a Scandinavian silver coin that weighed an average of 0.63 g in Norway. In Denmark and Sweden, the coin had different average weights. It was minted from 1483 to 1578. 1 hvide = 4 pennings. 3 Hvide = 1 Skilling. This corresponds to the Witte of the northern German states.

- ↑ The "Søsling" corresponded to the German " Sechsling ", a silver coin worth 6 pennings or ½ skilling.

- ↑ Woxen p. 587.

- ↑ Klippinge were square coins.

- ↑ Risvaag p. 198.

- ↑ Gimsø Mint

- ↑ Wilcke, pp. 151-156.

- ↑ “Of fine silver. The attempt to suppress bad things with good money. ” The window in the Kreissparkasse Cologne . Topic 168 (PDF; 4.2 MB). March 2006, p. 3.

- ↑ Wilcke, pp. 174-179.

- ↑ a b Wilcke pp. 186-198.

- ^ Mint in Christiania

- ↑ Wilcke introduction.

- ↑ Wilcke, “Otteskilling” in “Mønten paa Kongsberg”.

- ↑ Christian VII. With illustrations.

- ↑ a b c Eitrheim

- ↑ Eitrheim (2005) p. 12.

- ↑ Knut Mykland: Kampen om Norge 1784-1814 . Cappelens Forlag 1978. p. 34.

- ↑ Bernt Anker: Om Banker i Almindelighed med Hensyn til en local Bank i Christiania. Plan proposé for a banque locale à Christiania. In: Hermoder. Vol. 2, No. 6, Copenhagen 1796, pp. 1-36.

- ↑ "Assignationssedler" were a kind of government bonds that were to be redeemed later, that is, instructions on expected government revenue later. They were known from the time of the French Revolution. There they were supposed to be refinanced through the sale of the confiscated aristocratic and church property. But they should be circulable like money.

- ↑ "Riksbankdaler" was a currency that was newly introduced in the Danish Empire in 1813. It was valid until 1816. The exchange rate was 1 Riksbankdaler = 6 Riksdaler Kurant à 16 Skillings = 96 Danish Skillings. 1 Riksbankdaler = ½ Riksdaler species (= Mark Banco).

- ↑ Rygg p. 18.

- ↑ Eitrheim (2005) p. 13.

- ↑ Eitrheim (2005) p. 15.

- ↑ Michael Märcher: The Scandinavian flight fra sølvet .

- ↑ It was not until January 1, 1875 that 10 and 20 kroner coins could be used for payment, and it was only from this date that this system of coins was used.

- ^ Brief history of Norges Bank . (English, norges-bank.no [accessed June 28, 2018]).

- ^ The Scandinavian Coin Union (PDF; 469 kB), accessed on: May 16, 2010

- ↑ Norwegian Krone ( Memento of the original dated December 31, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.