Nosseni epitaph

The Nosseni epitaph is the partially preserved grave monument for the Swiss sculptor Giovanni Maria Nosseni . It was made in 1616 before Nosseni's death and stood in the Sophienkirche until it was severely damaged during the air raids on Dresden in 1945 . Parts of the epitaph are currently being presented to the public at various locations in Dresden .

history

Around 1600 Nosseni was considered to be “the most important artistic personality for Dresden”. He was a teacher for numerous later important Dresden sculptors and since his settlement in Dresden in 1575 he had made the sculpture of the Italian Renaissance known in the Electorate of Saxony . As a Saxon court sculptor and foreign artist, he enjoyed a high reputation. He designed works and supervised the execution, but was rarely active as a sculptor himself.

As a court sculptor, Nosseni was able to afford a burial in the Sophienkirche, which was designed as a burial church, which was only possible for the upper classes of the city due to the burial costs of 50 thalers. Nosseni was also connected to the Sophienkirche, as he had created the main altar of the church in 1606 on behalf of Electress Sophie .

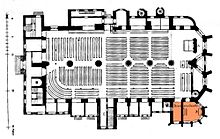

Four years before his death, Nosseni had his own grave monument erected. It was designed so that it could stand on one of the octagonal pillars of the Sophienkirche and therefore had a broken floor plan that formed three sides of an octagon. Nosseni's most important assistants Sebastian Walther and Zacharias Hegewald are considered to be the sculptors of the epitaph .

After Nosseni's death in 1620 the epitaph was attached to the westernmost fifth pillar of the church. When the interior of the Sophienkirche was rebuilt in 1875, the epitaph was moved "inconveniently in the Busmann's Chapel " and placed in a corner. At this point in time, the structure of the epitaph with a representation of the Last Judgment was lost. Instead, the epitaph was closed with a cranked entablature . Only during a second interior renovation of the church in 1910 was the epitaph "set up again in a preferred location in the church worthy of the master"; it was now on the first pillar next to the Nosseni altar.

In 1910, the epitaph consisted of two side reliefs with consoles and a crown, as well as a central niche, in front of which the sculpture of Ecce homo stood in the center. At the beginning of the Second World War , the sculpture was stored in the cellar of the Dresden Frauenkirche , which was considered bomb-proof. While the epitaph was badly damaged in the destruction of the Sophienkirche and the partially preserved reliefs are now in the Dresden City Museum , the Ecce homo was considered a war loss. The sculpture was only rediscovered in the collapsed western main vault of the church on April 7, 1994 while the Frauenkirche was being cleared. The figure was broken, but the details were so well preserved that it could be restored. It has been located in the Dresden Kreuzkirche since 1998 . Other fragments of the epitaph, including pieces of the crown, are stored in the State Office for the Preservation of Monuments in Saxony in the Dresden State House .

The design of the Busmannkapelle von Gustavs und Lungwitz memorial, a memorial for the Sophienkirche, also provides for the reconstruction of the Nosseni epitaph. It is to be built in the center of the stylized choir of the chapel on the site of the earlier altar. It is planned to use the chapel space for events and devotions, whereby visitors will usually look at the Ecce homo des Epitaphs, which “represents the suffering of the city, but also promises redemption”.

description

Left side

On the left side of the Ecce homo a kneeling male figure could be seen as an alabaster relief , which Nosseni himself depicted. The bearded man with short, sparse hair wears clothes typical of the time and kneels with his left knee on a pillow while the right knee is slightly raised. There is a coat over his shoulder and two foam coins adorn his chest . The fingers on both the right and left hand had already broken off around 1900; the left hand originally held a sword, but it was also missing around 1900.

The inscription gave the dates of Nosseni's life and his activities:

“JOHANNES MARIA NOSENIUS / Luganensis Italus natus / Aō. C. MDXLV. M. Maii / Sereniss. Augusti. Christi / ani primi. Christiani II. Et / Johannis Georgi electorū / Saxon. architectus. Fragi / litatis humanæ memor in / spem beatae resurrectionis / vivens sibi e tribus uxoribus. ”

“Johannes Maria Nosenius, from Lugano in the month of May, born Italian in the year 1545, the most serene and sublime Christian I, Christian II and Johann Georg, Elector of Saxony, architect. Mindful of human frailty in the hope of a blessed resurrection for himself and his three wives during their lifetime. "

In 1912 Robert Bruck found it remarkable that Nosseni was named in the inscription as an architect (“architectus”), but not as a sculptor. Only the relief of the left side of the epitaph has been preserved, with parts of the right foot missing. The bench with cushion on which the figure was kneeling has also not survived.

The Nossenis relief is considered "a masterpiece of elegant characteristics".

Middle page

The middle side showed a flat niche , which was bordered by Corinthian marble columns standing over corners . In front of the niche stood the 165 centimeter high stone sculpture on a four-sided plinth , which was called Ecce homo on the plinth . By 1900 the sculpture had already been painted over with gray oil paint.

Christ is represented with a crown of thorns , the left hip is pushed out from the viewer and the trunk is tilted to the right. The head - "the facial expression is painful, but without distortion" - is turned to the left and the hands are placed on top of each other to the right. A robe lies over the back and loin. The central sculpture is considered to be "one of the rare monumental free statues created by Germans at the time" and its posture shows clear, if exaggerated echoes of Michelangelo's sculpture The Risen Christ in Santa Maria Sopra Minerva in Rome .

The pedestal on which the Ecce homo stood contained verses from the Bible on three sides.

|

Left |

Middle |

Right |

right side

On the right side of Ecce homo, Nosseni's three wives kneeling are depicted on a relief. On the left, the first wife Elisabeth Unruh, who died in 1579, is shown in profile. She wears a death veil and looks up, her hands clasped in prayer.

In the center is Nosseni's second wife, Christiane Hanitsch, who died in 1606. On the outside, she is shown younger than Elisabeth and looks ahead. The right hand is open while the left hand is holding a prayer book . The figure is also wearing a death veil and seems to be deep in conversation with the woman behind her.

The woman shown on the right is Nosseni's third wife, Anna Maria von Rehen, whom he married in 1609 and who survived him. It was like Christiane shown more youthful, however, does not wear a veil dead, but a neck brace , a cap and a fur coat with grace chain.

All three women kneel on pillows and were composed in a small space next to each other. The alabaster relief is therefore, also with regard to the Nossenis relief, a “less successful group”.

The inscription under the relief gave the life dates of the wives:

“Elisabethæ. . . . na. XVII. Jul. / Aō. CMDLVII. defunctæ / February XIV. Aō. C MDXCI / Christina. na. XV. Decem. / Aō. CMDLXXV denatae / XXX. Nov. Aō. C MDCVI / Annae Maria superstitina / III. February Aō. C MDLXXXIX / Hoc / Monumen. poni cura / vit M. Sep. Aō. CMDC.XVI. "

“Elisabeth .... born July 17th, 1557, died February 14th, 1591; Christine. born December 15, 1575, died November 30, 1606; Anna Maria, still alive, (born) February 3rd anno 1589. He had this tomb erected in September anno 1616. "

As early as 1900, the fingers of the left and middle female figure were missing. The relief was preserved, but the substructure with the inscription was destroyed.

Executing sculptor

The exact assignment of individual parts of the epitaph to the sculptors who were to be executed is difficult. As early as the late 17th century, “the famous sculptors Walther and Hegewald” were named as executing sculptors. Her work on the epitaph was partly related to the Ecce homo by Gottlob Oettrich, for example, and in other cases to the entire epitaph.

In 1900 Cornelius Gurlitt referred to Gottlob Oettrich and, like him, assigned the Ecce homo to Sebastian Walther and Zacharias Hegewald. The lateral relief of Nosseni, on the other hand, is "of extraordinary mastery and can be traced back to Nosseni himself."

In 1912, however, Bruck pointed out that Nosseni did not “create sculptural commissions himself, but instead commissioned other artists or assistants in his workshop to carry out his designs”. He also recognizes “that two different hands were working on the work, [...] because the Ecce homo differs stylistically sharply from the alabaster reliefs on both sides.” By comparing styles, he assigned the Ecce homo to Zacharias Hegewald and the side alabaster reliefs to Sebastian Walther .

Walter Hentschel suspected that Sebastian Walther was mainly working on the epitaph, since Hegewald was only 20 years old in 1616 and therefore comparatively less experienced in the craft.

literature

- Robert Bruck : The Sophienkirche in Dresden. Their history and their art treasures . Keller, Dresden 1912, pp. 49–54.

- Cornelius Gurlitt : Descriptive representation of the older architectural and art monuments of the Kingdom of Saxony. Volume 21: City of Dresden, Part 1 . CC Meinhold & Sons, Dresden 1900, pp. 102-104.

- Walter Hentschel : Dresden sculptor of the 16th and 17th centuries . Hermann Böhlaus successor, Weimar 1966, p. 77.

Individual evidence

- ^ Robert Bruck: The Sophienkirche in Dresden. Their history and their art treasures . Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 45.

- ^ Robert Bruck: The Sophienkirche in Dresden. Their history and their art treasures . Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 15.

- ↑ Gottlob Oettrich: Correct list of those who died, together with their monuments and epitaphs, which found their rest inside in local churches in St. Sophia . Dreßden 1710/1711, p. 117.

- ^ A b Robert Bruck: The Sophienkirche in Dresden. Their history and their art treasures . Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 51.

- ↑ a b Cornelius Gurlitt: Descriptive representation of the older architectural and art monuments of the Kingdom of Saxony. Volume 21: City of Dresden, Part 1 . CC Meinhold & Sons, Dresden 1900, p. 104.

- ^ Robert Bruck: The Sophienkirche in Dresden. Their history and their art treasures . Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 38.

- ↑ Wolfram Jäger: Report on the archaeological clearing 1993/94 . In: Society for the Promotion of the Reconstruction of the Frauenkirche Dresden eV (Hrsg.): The Dresden Frauenkirche. 1995 yearbook . Hermann Böhlaus successor, Weimar 1995, pp. 19-20.

- ^ Image of the sculpture "Ecce homo" in the Dresden Kreuzkirche ( Memento from September 28, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Gerhard Glaser: The Sophienkirche memorial. A place of mourning, a place against forgetting . In: Heinrich Magirius, Society for the Promotion of the Sophienkirche (Ed.): The Dresden Frauenkirche. Yearbook on their past and present . Volume 13. Schnell + Steiner, Regensburg 2009, pp. 198-200.

- ↑ a b c d Cornelius Gurlitt: Descriptive representation of the older architectural and art monuments of the Kingdom of Saxony. Volume 21: City of Dresden, Part 1 . CC Meinhold & Sons, Dresden 1900, p. 102.

- ^ Robert Bruck: The Sophienkirche in Dresden. Their history and their art treasures . Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 50.

- ^ Georg Dehio: Handbook of German Art Monuments. Volume 1: Central Germany . Wasmuth, Berlin 1914, p. 81.

- ^ A b c d Walter Hentschel: Dresden sculptors of the 16th and 17th centuries . Hermann Böhlaus successor, Weimar 1966, p. 77.

- ^ Georg Dehio: Handbook of German Art Monuments . Volume 1: Central Germany. Wasmuth, Berlin 1914, p. 81f.

- ↑ Cf. Gottlob Oettrich: Correct list of those who have died, together with their monuments and epitaphs, which have found their rest inside in local churches in St. Sophia . Dreßden 1710/1711.

- ^ Robert Bruck: The Sophienkirche in Dresden. Their history and their art treasures . Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 49.

- ^ Robert Bruck: The Sophienkirche in Dresden. Their history and their art treasures . Keller, Dresden 1912, p. 52.