Lavender

| Lavender | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Lappet vulture ( Torgos tracheliotos ) |

||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| Scientific name of the genus | ||||||||||

| Torgos | ||||||||||

| Kaup , 1828 | ||||||||||

| Scientific name of the species | ||||||||||

| Torgos tracheliotos | ||||||||||

| ( Forster , 1791) |

The lappet vulture ( Torgos tracheliotos , Syn .: Aegypius tracheliotus ) is a very large representative of the Old World vulture (Aegypiinae). He inhabits large parts of Africa and parts of the Arabian Peninsula . Due to the continuing decline in the population, the IUCN classifies the species as endangered ("vulnerable") worldwide.

description

With a body length of 95–115 cm and a wingspan of 250–290 cm, this huge and very sturdy vulture is one of the largest Old World vultures and one of the largest birds of prey. The weight of birds from East Africa was 5.4–9.2 kg, with an average of 6.2 kg.

Lappet vultures of the nominate form are almost monochrome blackish dark brown. Back and upper wing-coverts are dark brown, wings and control feathers are a little darker black-brown on top. The chest and belly are streaked with strong brown on a white background, the basic white color is due to the downy plumage, the brown streaking is due to the loosely standing brown cover feathers. The lower wing coverts are just as dark as the wings, on the lower wing a narrow white band is formed due to the lack of covers. The cover feathers are missing on the sides of the neck and the legs, the exposed downs are also white.

The head, like the front of the upper neck, is featherless, wrinkled and colored pale pink. When excited, the bare head and neck areas turn more intense red. A brown and white ruff is indicated. The very large and strong bill is light yellowish horn-colored or greenish brown, the upper bill is very dark on the ridge. The wax skin is bluish; the featherless part of the legs and the toes are pale blue to gray. The iris is dark brown.

Fledglings are all brown, including the leg plumage, while the white areas on the chest and under wings of adult birds are covered by thicker cover plumage. The bare neck and head are pale pink, the bill is blackish horn-colored to yellowish gray. The legs are gray-brown. The coloring of the adult birds is achieved after six or seven years.

distribution and habitat

The distribution area of the lumpy vulture, which is split up into numerous individual occurrences, includes large parts of Africa and parts of the Arabian Peninsula.

The species inhabits dry landscapes hardly or not at all inhabited by humans, especially dry savannas with little or no grass cover on the ground, but also deserts and semi-deserts with trees and mountain slopes limited to wadis . When searching for food, areas with denser vegetation and areas more heavily used by humans, such as roadsides, are also sought out. The species occurs regularly up to an altitude of 3000 m, locally up to an altitude of 4500 m.

Systematics

In addition to the nominate form , another subspecies is recognized:

- T. t. tracheliotus ; Africa

- T. t. negevensis ; Arabian Peninsula; overall browner than the nominate form and the legs are also feathered brown. The head is more or less covered with gray-white dunes . In juveniles, the head and neck are grayish-white with at most a slight shade of pink.

nutrition

The food consists mainly of carrion , with large mammals as well as smaller mammals, birds and reptiles such as monitor lizards and other lizards are eaten. The nestling food consists mainly of smaller vertebrates . The animals also eat afterbirths and eggs from birds and turtles. It is assumed that lesser vultures also hunt prey from other birds of prey or that they hunt smaller vertebrates themselves, but it has been proven that they hunt adult and nest-young flamingos in colonies.

Like other vultures, lesser vultures search for food in a circling search flight at a higher altitude, but presumably also in a low search flight and possibly also from the hide when hunting for live prey. At least some of the foraging flights take place over long distances; in Israel, lappet vultures have been observed more than 150 km north of their breeding grounds. Carrion is found mainly through one's own search, less through observing other vultures; the species therefore often arrives first on the carcass. Lared vultures are the only African vultures capable of ripping the skin of large mammals. However, they apparently rarely do this and rarely eat pure meat. Although they are dominant compared to other vultures on the carrion, they usually stay on the edge of larger vultures and then mainly eat bits of skin, sinews and other coarse remains. Even on larger carcasses there are often only one or two or a maximum of 10 individuals; where the species is frequent, however, 25–50 animals can also be gathered.

Reproduction

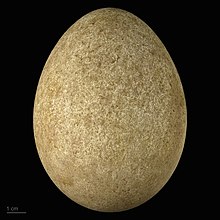

The species breeds singly in pairs. The breeding season varies depending on the geographical distribution, it falls in northern Africa and on the Arabian Peninsula in the period from November to July or until September, in parts of East Africa it is incubated all year round and in southern Africa from May to January. The nest, up to 2.2 m wide and 0.3–0.7 m high, is built at a height of 3 to 15 m on the crown of an acacia or other small tree. It consists of branches and is padded with scraps of fur, hair and dry grass. The one or two white eggs with brown spots are incubated for 54–56 days, normally only one young bird fledges.

Due to the strong sunlight, the young bird has to be shaded almost continuously by its parents up to an age of around 30 days. After that, the shading is less complete; however, it is only stopped when the nestling has developed the dorsal feathers at the age of 65 to 78 days and is sufficiently capable of regulating its body temperature. As with many vultures, the returning adult chokes the food on the edge of the nest. The young bird is fed by an adult bird until it is 30 days old, after which it can eat independently from the edge of the nest. At the age of 55 to 68 days, he begins to beg for food by aggressively chopping the beak of the adult birds. At the beginning of this phase, an adult bird no longer sleeps on the nest, but on a neighboring tree. The young bird begins flying exercises at around 90 days, and leaves the nest between 125 and 135 days. The young birds then remain dependent on their parents for four to six months.

Existence and endangerment

The population development varies greatly from region to region, but overall the population has decreased significantly over the last 80 years or so. The lumpy vulture has been extinct in Algeria and Tunisia since the 1930s, in Western Sahara in the 1950s and in Morocco in the early 1970s, and only small populations have survived in southern Egypt and possibly also in Mauritania . In Saudi Arabia at least 500 ears vultures with increasing tendency live. The population in Nigeria has plummeted since the late 1970s and today the species there may have become extinct, and the species is no longer a breeding bird in Israel . The population in the whole of southern Africa is slowly declining. The IUCN estimates the total population in Africa to be at least 8,000 birds.

The main causes of the decline are poisoning by poison bait as well as direct persecution, since the species is assumed to have captured domestic animals. Other factors that endanger the survival are disturbances in the nest, declining food and habitat destruction. Due to the continuing decline in the population, the IUCN classifies the species as endangered ("vulnerable") worldwide.

swell

literature

- M. Shobrak: Parental Investment of Lapped-faced Vultures Torgos tracheliotos during breeding at the Mahazat as-Sayd Protected Area, Saudi Arabia. In: RD Chancellor and B.-U. Meyburg (eds.): Raptors worldwide. World Working Group on Birds of Prey, Berlin and MME-BirdLife Hungary, Budapest 2004, ISBN 963-86418-1-9 : pp. 111–125.

- James Ferguson-Lees , David A. Christie: Raptors of the World. Christopher Helm, London 2001, ISBN 0-7136-8026-1 , pp. 124-125 and 439-442.

Web links

- Torgos tracheliotos in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2008. Posted by: BirdLife International, 2008. Accessed October 15 of 2008.

- Videos, photos and sound recordings of Torgos tracheliotus in the Internet Bird Collection