Manching oppidum

The Manching oppidum was a large Celtic city-like settlement ( oppidum ) near today's Manching (not far from Ingolstadt ). The settlement was founded in the 3rd century BC. Founded and existed until 50–30 BC. In the late Latene period , in the second half of the 2nd century BC. BC, the oppidum reached its greatest population density and extent with an area of 380 hectares . At that time, 5,000 to 10,000 people lived within the city wall, which was around 7.2 kilometers long. The Manching oppidum was thus one of the largest settlements north of the Alps. The settlement, whose ancient name is not known, was probably the main town of the Celtic tribe of the Vindeliker .

Research history

The large ring wall near Manching, which survived the settlement as a distinctive ground monument , had already attracted attention in Roman times and was preserved as a landmark for centuries, for example as a municipality and diocese border. The first description was made by the Lyceal professor Joseph Andreas Buchner (1776-1854) in 1831, who believed to have found the Roman Vallatum . The first excavation was carried out in 1892/93 by Joseph Fink (1850–1929), but only Paul Reinecke recognized in 1903 that the Manching wall was a Celtic oppidum.

As part of the German military armament, the Luftwaffe built an airfield in Manching 1936–1938. Large parts of the oppidum were destroyed without giving the monument preservation an opportunity to examine the area. During this time only a few finds were recovered by the site management. In 1938 Karl-Heinz Wagner carried out an excavation on the north-eastern part of the ring wall. He discovered that the wall contains the remains of a wall and described it as Murus Gallicus . Because of the airfield, Manching was the target of numerous bomb attacks during the war years, which contributed to the further destruction of the findings.

1955–2015 the Roman-Germanic Commission of the German Archaeological Institute led the research and carried out extensive excavations in Manching together with the Bavarian State Office for Monument Preservation :

- 1955–1961 “Central Area” under Werner Krämer

- 1962–1963 "Osttor" under Rolf Gensen

- 1965–1973 “central area” and southern bypass under Franz Schubert

- 1984–1987 Northern bypass under Ferdinand Maier

- 1996–1999 “Altenfeld” under Susanne Sievers

- 1990–2008 Manching-Süd (EADS, DASA, StOV) by excavation companies and various employees of the RGK under the overall direction of Susanne Sievers

In 2018 an area of around 7.3 hectares (“Airbus”) in the south of the oppidum was examined by an excavation company.

By 1987 about 12 hectares of the settlement area had been examined. At the end of 2002, 26 hectares had already been recorded. Manching is therefore the best researched oppidum in Central Europe. With the exploration of ever larger parts of the settlement, the progressive destruction of the oppidum went hand in hand, since some of the investigations were carried out as rescue excavations in front of the development.

Finds from the Manching oppidum have been exhibited in the Celtic-Roman Museum in Manching since 2006 .

Settlement structure

The oppidum was strategically located at the intersection of two trade routes in north-south and east-west directions. In addition, there the couple flowed into the Danube at that time , and long-distance trade was also carried out via river shipping on the Danube. An oxbow river of the Danube was turned into a port in the northeast of the settlement. Manching was probably the most important trading and economic center of the late Latène period north of the Alps.

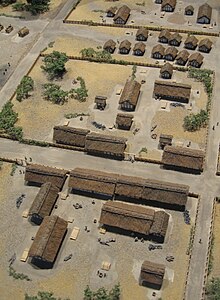

The settlement was laid out and constructed according to plan. Aligned with the cardinal points, it was divided into plots that were enclosed like a courtyard. The interpretation of these square structures is controversial. It could have been self-sufficient farmsteads that are reminiscent of Hallstatt- era mansions . This typical rural form of settlement does not seem to be confirmed by recent findings. Today it is more likely that the square layouts represent areas with specialized areas of life that included agriculture, handicrafts and cult. The excavations at the "Altenfeld" confirm this assumption, as a real handicraft quarter was excavated there.

A temple was found in the center of the settlement, which probably goes back to the founding time. This center was from the end of the 4th century BC. Until the 2nd and 1st centuries BC. Used. Depots of weapons, harness and boiler parts, a paved square and a large number of toddler and baby bones refer to the cultic use of the area. So far, three other complexes have been found that contain special structures that can be interpreted as a sanctuary.

Along the east-west street, which connected the east gate with a hypothetical west gate, there were small huts, the findings of which indicate points of sale of merchandise. A similar route probably led from the south gate to the north of the settlement.

The settlement was not consistently densely populated. The core area ("central area") formed the relatively dry alluvial land between the supposed west and east gates. The population density thins towards the edges. For an outer zone, a strip up to 500 m wide adjoining the wall, no development is discernible. These areas were likely used as arable land and pasture.

Single-room or multi- room post houses with a floor area between 40 m² and 100 m² have been proven for the development . Sometimes half-timbered houses are also assumed. Longhouses , pit houses , storage buildings on stilts, storage pits, workshops and wells complete the picture. Many floor plans are multiples of half a Celtic foot (15.45 cm). A rod interpreted as a yardstick with bronze rings of this length was excavated by Franz Schubert.

The large variety of keys and locks in the large Celtic settlement is remarkable. The people obviously had possessions that were worth protecting, and because of the close coexistence of many people, they also had an increased need for security. Slide bolt locks and hook keys were used for doors and gates, drop bolt locks for rather smaller doors and spring locks for boxes and chests.

nutrition

There are several indications that agriculture was also practiced within the settlement. Fields may also have stood on the edge of the settlement. In its heyday, however, the oppidum was certainly dependent on food supplies from the surrounding area. Barley and spelled were predominant . In addition, was millet , einkorn , emmer , oats , wheat and rye grown. Also lentils , field beans , opium poppy , hazelnuts and pome fruit were on the menu.

A huge amount of animal bones is evidence of intensive cattle breeding, and Manching may also have been a supraregional cattle market. Primarily it was pigs and cattle (also as draft animals), followed by sheep (wool) and goats (milk and cheese). The chicken played no significant role. Horses and dogs were also eaten, but not bred for it.

The location of the settlement on streams and rivers suggests that fishing was practiced. This has also been proven in recent years through intensive investigations into pit backfilling. The rest of a Mediterranean fish sauce ( garum ) could also be discovered here.

economy

The settlement had an extensive iron industry, but its products were primarily intended for personal use. The iron ore was mined in the vicinity of the Danube and Feilenmoos . Among other things, numerous specialized tools were manufactured, which are evidence of a lively craft activity. Manching is also a production center for glass beads and glass arm rings. The focus was on the color blue. Pottery, jewelry making and textile processing were also carried out at a high level.

Finds such as amber from the Baltic Sea coast and wine amphorae from the Mediterranean area show that there was trade throughout Europe. There are also luxury crockery ( Campana ), bronze crockery and jewelry.

A separate system of coins was used for inner-city trade, which consisted of small silver coins and tuft quinars , as well as base bronze ( potin ). For long-distance trade, gold and from around the beginning of the 1st century BC were used. Silver coins were also used. The gold coins minted in Manching have a strong bowl-shaped curvature ( rainbow bowl ). Counterfeit money was also in circulation, for example bronze coins coated with gold. Fine scales were used to check the authenticity and value of the coins .

Attachment

The first city wall was built around 150 BC. Erected as Murus Gallicus . Why this wall was erected is unknown, but in addition to a possible threat to the settlement, reasons of prestige may have played a not insignificant role. This function is expressed in particular by the monumentality of the gate systems. From the settlement side, the wall was reinforced by a nine meter wide ramp. Around 104 BC The second city wall was built as a post slot wall , which was renewed in the same construction scheme when the third wall was built.

The Igelsbach coming from the southwest was diverted to the Paar along the city wall. Before the emergence of the oppidum, it ran across the settlement area in Riedelmoos. A moat was created in the southwest.

The east gate of the settlement has been particularly well researched and can be viewed as a reconstruction (albeit in the south of the ring wall) or as a ground monument. It is a pincer gate , but the actual appearance of the superstructure is unknown. This gate was made in 80 BC. Chr. Destroyed by fire, the rubble was left in place. This indicates that the path that led through the gate was no longer used.

Scrap metal recycling

In the "Altenfeld" excavation area, an intensive use of scrap metals could be demonstrated. Because metals were valuable because of the need for transport, it can be assumed that this was a common practice in pre-industrial times. The in the 1st century BC Finds from the last phase of settlement dated to the 3rd century BC could indicate that the decline of the settlement was already noticeable and that the recycling of raw materials was even more necessary.

Burials

Large amounts of human bones are distributed over the settlement area, which at the beginning of the exploration served as evidence of a violent demise of the settlement. Today forms of cult of the dead are suspected, but cannot yet be interpreted in more detail. The two-stage burial has been proven several times. Body parts were removed from the not yet fully skeletonized corpse (preferably long bones) and stored separately (as relics ?) Or deposited (for example in the form of skull nests). The amount of people in southern Germany between the 4th and 2nd centuries BC Burials found in BC are generally very small compared to the associated settlements. Only a small part of the population was buried in such a way that the graves can be uncovered using today's archaeological methods.

Burial grounds

The grave fields "Hundsrucken" and "Steinbichel", which were built at the end of the 4th century BC, are associated with the oppidum. And their most recent burials in the 2nd century BC. To be dated. The grave field "Hundsrucken" (22 graves) was located in the northeast within the later city wall and was probably given up due to the expansion of the settlement. “Steinbichel” (43 graves) lies beyond the couple. The graves of the two grave fields probably only housed the top of the society of that time, which is underlined by the high number of arms bearers and the rich equipment of the women's graves.

Significant finds

Among the numerous individual finds from the excavations, some pieces have achieved independent fame.

In 1999 a gold coin depot was discovered near the port . It comprises 483 Boische mussel staters and a 217 g gold nugget. Three little bronze rings indicate the closure of an organic container.

In 1984 a golden cult tree was recovered during the excavation " Northern bypass" . Bronze leaves (ivy), gold-plated buds and fruits (acorns) are inserted into a wooden trunk covered with gold leaf, which also has a side branch. The cult tree is interpreted as an oak shoot entwined with ivy. The piece is from the 3rd century BC. Dated. The tree was in a wooden box also decorated with gold leaf.

A horse sculpture from the 2nd century BC interpreted as a cult image . In contrast to comparable horse representations, it is not made of bronze, but of sheet iron . Only the head (without ears) and remains of the legs were found.

The end of the oppidum

For a long time it was assumed that the Roman invasion led to the destruction of the settlement. Complete conquest or destruction is now considered unlikely. The march of the Cimbri and Teutons around 120 BC could Have led to a warlike conflict. However, the end of Manching was triggered by the collapse of the economic systems that accompanied the Caesarian conquests in Gaul. A steadily decreasing population led to the desolation of the settlement and the decline of the city wall, which could no longer be maintained. When the Romans arrived in 15 BC Only the remains of an imposing city wall remained of the once flourishing city.

Later, the Romans built a road station at almost the same location, which is entered in Roman itineraries as Vallatum . In addition, they used the limestone of the wall for their own raw material extraction, which is proven by found lime kilns. In the middle of the 1st century AD, however, the nearby Oberstimm was chosen as the building site for a fort , which is probably due to the fact that the old Celtic settlement had meanwhile lost its connection to the Danube.

literature

The good state of research is reflected in numerous publications, which can only be considered here in extracts:

- The German Archaeological Institute has so far published 21 publications in its Die Ausgrabungen in Manching series (as of October 2019).

- Susanne Sievers : Manching: The Celtic city . Theiss, Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-8062-1765-3 ( http://www.dainst.org/spuren/index_3354_de.html ( Memento from September 29, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) ).

- Sabine Rieckhoff : The fall of the cities. The collapse of the Celtic economic and social system . In: C. Dobiat, S. Sievers, Th. Stöllner (eds.): Dürrnberg and Manching. Economic archeology in the East Celtic region . Files from the international colloquium in Hallein 1998, Bonn 2002 [2003], ISBN 3-7749-3027-9 , pp. 359–379.

- Hermann Dannheimer, Gebhard Rupert (Ed.): The Celtic Millennium . Exhibition catalog Prehistoric State Collection Munich, Museum of Prehistory and Early History. Zabern, Mainz 1993, ISBN 3-8053-1514-7 .

- Michèle Eller, Susanne Sievers , Holger Wendling, Katja Winger: Centralization and urbanization - Manching's development into a late Celtic city . In: S. Sievers, M. Schönfelder (Ed.): La question de la proto-urbanization á l'âge du Fer. The question of protourbanization in the Iron Age. Files from the 34th AFEAF International Colloquium from 13-16 May 2010 in Aschaffenburg (Coll. Pre and Morning 16). Bonn 2012, ISBN 978-3-7749-3785-7 , pp. 303-318.

- Holger Wendling: Manching Reconsidered. New Perspectives on Settlement Dynamics and Urbanization in Iron Age Central Europe . European Journal of Archeology 16 (3), 2013, pp. 459-490.

- Holger Wendling, Katja Winger: Aspects of Iron Age Urbanity and Urbanism at Manching . In: M. Fernandez-Götz / H. Wendling / K. Winger (Ed.), Paths to complexity - Centralization and Urbanization in Iron Age Europe. Oxford 2014 ISBN 978-1-78297-723-0 , pp. 132-139.

Web links

- Celtic-Roman Museum Manching

- DAI brief description of the oppidum

- DAI reconstruction drawing of the east gate ( Memento from September 21, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- "50 years of excavations in the oppidum of Manching 1955-2005" , DAI internet magazine " Traces of the Millennia" , No. 3, 2005 (very comprehensive, many images)

- Coins from Manching

- Archaeological finds from the Oppidum Manching in the culture portal bavarikon

- Rainbow bowl - the coins of the Celts from Manching: collection in bavarikon

Individual evidence

- ^ Annual meeting of the Roman-Germanic Commission. DAI, accessed April 5, 2016 .

- ^ The Archaeological Year in Bavaria . Born in 2001. “New findings on the development of the cultural landscape in the Ingolstadt-Manching area during the Bronze and Iron Ages” p. 68ff.

- ^ Sievers: Manching - the Celtic city . P. 109ff.

- ^ Archeology in Germany . Issue 2/2006. “Dual system at the end of the Iron Age” p. 6 ff.

- ^ Results for excavations in Manching. ZENON DAI (literature research at the Humboldt University of Berlin), accessed on February 19, 2016 .

Coordinates: 48 ° 43 ′ 0 ″ N , 11 ° 31 ′ 0 ″ E