Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy

The percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy ( PEG ) is an endoscopically created artificial access from the outside through the abdominal wall into the stomach or - in the case of a percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy ( PEJ ) - into the small intestine . An elastic plastic tube can be placed through this access . However, the abbreviations PEG or PEJ regularly designate the probe guided through the respective access. The PEG probe is mainly used to supply the patient with food and fluids, but it can also be used to drain secretions or to administer medication, which must be suitable for this type of application .

The other nutritional methods should be considered when deciding on a PEG. Since the application of a PEG, one of the most common medical interventions in Germany, is a surgical procedure , legal and ethical aspects must be observed and taken into account.

term

The term “percutaneous” is derived from Latin and can be translated as “through the skin”. Gastrostomy is made up of the two Greek parts of the word gaster for stomach or abdomen and stoma for mouth or opening.

history

The first PEG was on 12 June 1979 at Rainbow Babies & Children's Hospital, University Hospitals of Cleveland (USA) by Michael WL Gauderer, pediatric surgeon , Jeffrey Ponsky, endoscopy doctor , and James Bekeny ( Surgery - Medical Assistant old at a 4.5 months) Child with insufficient oral food intake. The inventors, Michael WL Gauderer and Jeffrey Ponsky, published this technique in 1980, details of the development of the method were published by the author in 2001.

In Germany, the first such interventions were carried out in Cologne in 1984 by Vestweber and by Michael Keymling in 1986 in the Bad Hersfeld district hospital.

task

The PEG tube bypasses the nasopharynx, esophagus and stomach entrance. This PEG tube is therefore used for partial or complete enteral nutrition when oral feeding is not possible or only inadequately possible. However, it can also be used as a drainage option if vomiting persists , for example in the case of an intestinal obstruction .

A direct puncture of the jejunum is known as a percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy (PEJ probe). A dual lumen probe, each with a leg in the stomach and - via the pylorus ( pylorus ) and the duodenum ( the duodenum ) addition - in the uppermost section of the small intestine, the jejunum ( jejunum ), a JET-PEG . A PEJ or JET-PEG can be useful in cases of narrowing ( stenosis ) of the stomach outlet and other diseases.

Indications

General indications

If a long-term nutritional therapy intervention is planned (longer than four weeks), the insertion of a percutaneous tube may be indicated. It is suitable for patients who cannot or cannot swallow easily, so:

- In the case of mechanically caused swallowing disorders (diseases of the mouth, throat, esophagus and stomach entrance, e.g. tumors, scarring after chemical burns; injuries or operations in the face and head area).

- in neurogenic swallowing disorders (neurogenic dysphagia ) with a risk of aspiration , for example in neurological diseases such as stroke , brain tumor and apallic syndrome .

- with impaired consciousness ( vigilance disorder ).

- in certain forms of severe malnutrition , e.g. B. caused by cancer (especially a catabolic metabolic situation in the context of radiation and / or chemotherapy) that cannot be remedied otherwise, or in the case of short bowel syndrome

- if there is a risk of swallowing disorders accompanying the treatment or disease of the mouth, throat, esophagus and stomach entrance, e.g. B. ( stenosing ) tumors.

- if there is a narrowing ( stenosis ) of the gastric outlet (PEJ probe).

Indications in the terminal phase of life

In this area a clear change in the indication can be seen. Decreasing your intake of food and fluids is part of the natural process of dying. The tube feeding of this group of patients was based on the intuitive assumption that this would preserve and increase the physical and emotional well-being of the patient and thereby increase life expectancy. In the meantime, this theory has been refuted by numerous studies. Apart from that, it must be taken into account that the probe installation is not a nursing but a therapeutic intervention and therefore requires consent or must be in accordance with the presumed patient's wishes.

In the event of persistent severe vomiting or miseries due to inoperable gastroduodenal occlusion - e.g. B. in pronounced peritoneal carcinosis - a PEG can be applied to drain the secretions. This is useful, for example, if drug treatment fails, the patient will probably need the probe for more than two weeks and their likely life expectancy is also several weeks.

Contraindications

There are reasons that speak against a PEG tube. These are listed below:

- In an enlightened, mentally conscious state, the patient has refused to be fed artificially or by means of a tube or has objected to the installation of a tube or PEG (free choice of doctor and treatment).

- The patient can eat and drink in sufficient quantities.

- He is very restless and not reliably oriented towards the situation, so that he could injure himself by pulling on the probe.

- There is a disorder in the intake of food in the stomach ( malassimilation ).

- There is a passage disruption in the intestine .

- There is massive ascites .

- The patient is very obese .

- The patient suffers from inflammation of the peritoneum ( peritonitis ).

- There is a catheter in the peritoneum for peritoneal dialysis .

- The coagulation disorders are too severe.

- There is inflammation of the pancreas ( pancreatitis ).

- There is no endoscopic approach.

- There is a shock or an acute metabolic imbalance.

- There is a perforation of the gastrointestinal tract.

Selection of the appropriate probe shape

When deciding which type of probe to use for the individual patient, the following aspects must be considered:

- the treatment goal, the time horizon of application and the question of whether palliative care or temporary care is intended or necessary

- the resilience (physical, mental, psychological) of the patient

- the quality of life perceived by the patient

- The possibilities for implementation, in particular the availability of the methods and probes, set limits.

- The maintenance and care of the selected probe must be guaranteed.

- The likely form of treatment for the patient, be it inpatient, outpatient or changing, must be considered.

Nasogastric tube

The nasogastric tube is mainly suitable for short-term use in a stationary environment. It is suitable for short-term, rapid use, as no surgical intervention or gastroscopy is necessary. A probe that runs through the mouth or nose can be aesthetically pleasing, irritate the nasopharynx and lead to pressure necrosis and inflammation.

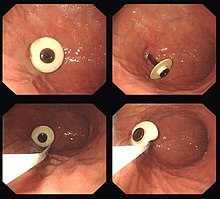

PEG

The PEG is suitable for medium and long-term use. The shape of the button probe is suitable for a medium period of time (6 months of use). Compared to the nasogastric tube, the PEG has the advantage that it can be left as long as it is needed or is likely to be needed.

The risk of aspiration is reduced. The act of swallowing is also not impaired, so that the patient can continue to ingest food and liquid through the mouth - if there are no other reasons that speak against it. A PEG thus enables enteral nutrition , i.e. nutrition via the gastrointestinal tract , which is fundamentally preferable to parenteral nutrition , i.e. nutrition through infusions.

The PEG is aesthetically less disruptive because the outer tube opening is not fixed on the face but on the abdominal wall. Although percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy is a low-risk procedure, the risk of which is equivalent to that of a gastroscopy , the patient's resilience and contraindications for an operation must be checked.

A PEG can also be used in the context of palliative medical symptom treatment to relieve the intestine in the case of intestinal obstruction .

Witz Fistula

Compared to the creation of a Witzelfistula , the PEG is a less stressful surgical procedure.

Possible problems

- The PEG tube requires supervision and maintenance. Some patients are mentally or physically unable to do this.

- Proper use is time-consuming.

- The elimination of the incentives to eat , such as the taste and smell of a normal meal, can lead to loss of appetite and subsequently to malnutrition .

Probe with holding plate and balloon probe

A balloon probe requires maintenance of the balloon filling in addition to maintenance when in use. The balloon probe is easily exchangeable and can be used to replace a probe with a retaining plate.

Creation of a PEG

Procedure

The creation of a PEG is carried out as part of a gastroscopy . Most often this is done with the so-called thread pull-through method. First, the patient's stomach is inflated by blowing in air. A favorable position for the probe is sought in the darkened room by means of diaphanoscopy . After applying a local anesthetic and appropriate disinfection, an incision a few millimeters long is made in the abdominal skin. A steel cannula is inserted through this incision into the stomach. A plastic tube is slipped over the steel cannula, which creates a connection through the skin into the stomach when the steel cannula is withdrawn. A thread is now pushed through this tube, which is grasped in the stomach with small forceps pushed through the endoscope . The endoscope is now withdrawn until the thread passes through the abdominal wall, stomach, and esophagus and protrudes out of the patient's mouth. The probe is then tied to this end and finally pulled outwards through the mouth, the esophagus and the stomach by pulling the end of the thread protruding from the abdomen. A plastic plate (inner retaining plate) is attached to the inner end of the probe, which prevents the probe from slipping outwards. The probe is fixed from the outside by a counter plate, also known as the outer holding plate. The counterplate should be pulled gently over night, but with a relatively firm pull for the first three days after the tube placement, so that the pierced layers of the abdominal wall and stomach grow together and a tight channel is formed.

Possible complications with the installation

The complication rate of PEG placement is quite low (estimated rate of severe complications <1%), as most endoscopic departments have already performed it in large numbers and are familiar with the method. Even so, there can be some typical complications.

- When applying the PEG, abdominal organs can be injured, e.g. B. a loop of intestine that comes to lie in front of the stomach during the puncture. This is very rare. Injuries to other organs (aorta, pancreas, liver, gallbladder, spleen, heart, etc.) are in principle conceivable in extreme cases.

- The small hole in the stomach through which the probe passes can possibly cause a leak through which stomach contents can enter the abdominal cavity. When this happens, peritonitis (inflammation of the peritoneum) can develop, which can become threatening to the patient and require surgery.

maintenance

Probe mobilization and dressing changes

Three days after application, the outer retaining plate should be loosened and the probe should be carefully pushed 3–4 cm into the stoma canal and then gently withdrawn until there is resistance (inner retaining plate hits the stomach wall). This mobilization of the probe prevents the inner retaining plate from growing into the stomach wall ( buried bumper syndrome ) and the PEG from possibly no longer having to be removed endoscopically, but only surgically. The probe should then be fixed on a slit compress with a margin of half a centimeter to one centimeter in the outer holding plate. A daily dressing change under aseptic conditions is indicated for the first ten days , then - if the stoma is free from irritation - two to three times a week. When the ostomy canal has healed completely and has no irritation after about two to four weeks, no more bandages are needed. The probe mobilization must nevertheless take place regularly.

Use of the PEG

handling

The artificial feeding can start about a day after the application.

- Feeding

Tube feeding, fluids, and medication suitable for this mode of administration

- with syringes by hand or

- by gravity flow with the food container above the access, or

- placed in the stomach with special feeding pumps.

Possible complications in use

- If too large amounts of fluid are accidentally passed into the stomach in too short a time, vomiting can occur. In the case of a helpless patient, there is a great risk of aspiration ; H. inhaling vomit. This can cause life-threatening pneumonia (aspiration pneumonia). According to individual studies, the probability of this complication in geriatric patients is just under 50%. The risk of aspiration can be reduced by elevating the upper body during administration. In addition, only small amounts should be administered in each case or, if a feeding pump is used, the delivery frequency should be set to a rather low level.

- Because of the risk of the holding plate growing into the stomach wall and abdominal wall (so-called buried bumper syndrome ), the PEG should be mobilized the first time the dressing is changed after it is applied - and from then on regularly every two to three days. The German Society for Nutritional Medicine has guidelines for the various reasons for use (indications) and application situations.

- Blockage of the tube by thickened food or unsuitable drugs, e.g. B. ground- release or other film-coated tablets. Numerous tips are given for eliminating this complication.

- Accompanying that is oral care to protect against thrush or periodontitis necessary if no oral food or drink is done more.

- People who are not situationally oriented can experience severe restlessness, which makes it difficult or impossible to properly supply food. Nursing staff may then react with impermissible deprivation of liberty measures in order to be able to ensure the administration of food.

- PEG tube feeding can cause diarrhea in some cases. In this case, the type or amount of nutrition must be adjusted accordingly (e.g. lower fiber content).

- The skin around the PEG entry point can become inflamed.

- If there is a leak or if the tube outlet is displaced, the administered fluid will not flow into the stomach, which can lead to peritonitis.

Replacement probes

- Gastrotube : The probe has a blockable balloon inside and can therefore be exchanged without endoscopy. It can also be used as a replacement for a probe with a retaining plate.

- Button probe : The percutaneous exchange probe has a balloon or other device on the inside to carry out a change, and on the outside no tube, but only a button with a lid, which can be worn inconspicuously under clothing. A connector is connected for probing. A button is usually used after a PEG has already been created. In rare cases, however, a button is surgically created.

Removal of the PEG tube

If the patient can eat enough himself again, the PEG tube can be removed again. There are two ways to do this:

- Cut the probe off the outside of the skin of the abdomen, push the protruding end of the probe into the stomach and wait for the inner part of the probe to exit through the intestines.

- Carry out another gastroscopy and, after detaching the outer retaining plate, remove the probe via the esophagus using a grasping forceps with the gastroscope .

- When using a probe with a soft, collapsible inner holder, the probe can be pulled through the stoma.

So far it is not entirely clear which of the first two methods is better. With the first method, there is a higher risk of ileus due to the foreign material in the probe. The second method is more complex and requires a new gastroscopy as described.

The abdominal fistula usually closes within a few hours and usually does not cause any problems.

Probe dependence

In infants or small children, if the PEG is used for a long time, it can lead to a tube dependency or dependency. This is understood to mean the unintentional physical and emotional dependence on a probing originally planned as only temporarily in the absence of a medical indication. Permanent feeding through a tube results in a development deficit in the development of the child, which is why its removal often appears to be indispensable.

Legal and ethical aspects

The installation of a PEG tube and any form of artificial nutrition is a medical intervention in the integrity of the human body. The doctor therefore needs the consent of the patient or his authorized representative. Whether a PEG tube is still necessary or can be removed must be checked at regular intervals. Even if a PEG is often the only way to ensure a person's nutrition in the long term, the following should be considered:

- A PEG alone does not guarantee satisfactory nutrition. According to a study published by the medical service of the Hessian health insurance companies in 2003, almost 27% of the people who were cared for over the long term via the PEG were underweight.

- Even if the PEG diet is ongoing, all options should be exhausted to eat or drink naturally, provided there are no medical reasons to the contrary. Eating and drinking are important social acts and convey a crucial quality of life . Entering meals means caring for the patient and at the same time serves to train the natural intake of food again or not to unlearn it at all.

- . Placing a PEG tube in dying is a life-saving measure constitutes If a living will in which the patient "Life-prolonging measures" rejects before, may, after a decision by the Federal Court of 17 March 2003 (BGH, in New Legal Wochenschrift 2003 P. 1588 ff.) Life-prolonging measures are no longer taken, i.e. feeding tubes are not put on, nor can artificial feeding be started. On June 8, 2005, the Federal Court of Justice specified this assessment to the effect that artificial feeding carried out against the patient's will is an illegal act, the omission of which the patient must fail to comply with in accordance with Section 1004, Paragraph 1, Clause 2 of the German Civil Code (analogous) in conjunction with Section 823, Paragraph 1 BGB, which would also apply if the coveted omission would lead to the patient's death. If the patient's legal representative demands the cessation of artificial feeding that has already been carried out, the BGH has deemed a guardianship court approval to be necessary in the first-mentioned decision.

According to the basic principles of medical ethics (" informed consent ", sole status of the medical indication), it is not justified to put a PEG tube on a patient just to e.g. B. to speed up the time-consuming eating procedure.

It is questionable to what extent a patient who no longer has any desire to eat can speak of conscious refusal to eat or only of particularly severe loss of appetite. Where there is no need, one cannot speak of a refusal. The view that patients who “don't want to eat any more” signaled that they want to die, and that any artificial feeding violates the patient's will is just as problematic as force-feeding to extend life at any cost. A decision for or against the installation of a PEG can therefore only be made individually and depending on the situation.

See also

literature

- Anika Rosenbaum, Jürgen F. Riemann, Dieter Schilling: The percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG). In: German Medical Weekly 2015; 140 (14), Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart 2015, pp. 1072-1076. DOI: 10.1055 / s-0041-103316

- Wolfgang Hartig, Hans Konrad Biesalski, Wilfried Druml, Peter Fürst, Arved Weimann: Thieme Verlag (ed.): Nutritional and infusion therapy: standards for clinics, intensive care units and outpatient departments 2004, ISBN 3-13-130738-2 .

- Kabis Fresenius Germany: Freka PEG Set Instructions for use Ref. 7751532 .

- Susanne Liese: Comparison of the Freka PEXACT system and the thread pull-through method for creating a PEG with regard to inflammatory complications and metastasis in the gastrostomy fistula in patients with epithelial tumors of the upper gastrointestinal tract and larynx 2014. DNB 1059896354

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Claudia Bausewein , Susanne Roller, Raymond Voltz (eds.): Guide to Palliative Care. Palliative Medicine and Hospice Care Elsevier, Munich, 2015, p. 391

- ↑ What to watch out for with probes. Pharmaceutical Newspaper, March 9, 2009, accessed October 18, 2019 .

- ↑ Thomas Heinemann, Klaus Herz, Andrea Tokarski, Luise Scholand, Gerhard Robbers: Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) and jejunostomy (PEJ) - internal ethical guideline for the ctt . Ed .: Cusanus Trägergesellschaft. Trier ( ethikkomitee.de [PDF]): “The simple installation and maintenance of the PEG / PEJ tube as well as the enteral feeding can lead to a generous application of the procedure, which, on critical examination, raises questions about its justification. When deciding to use a PEG / PEJ probe, medical, nutritional, nursing, ethical and legal issues must be taken into account "

- ↑ a b Gauderer MW, Ponsky JL, Izant RJ: Gastrostomy without laparotomy: a percutaneous endoscopic technique . In: J. Pediatr. Surg. . 15, No. 6, 1980, pp. 872-5. doi : 10.1016 / S0022-3468 (80) 80296-X . PMID 6780678 . .

- ^ Gauderer MW: Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy - 20 years later: a historical perspective . In: J. Pediatr. Surg. . 36, No. 1, 2001, pp. 217-9. doi : 10.1053 / jpsu.2001.20058 . PMID 11150469 . .

- ↑ Keymling M., Schlee P., Wörner W .: The percutaneous endoscopically controlled gastrostomy . In: : German medical weekly . tape 112 (1987) , pp. 182-183 .

- ↑ D. Schwab, M. Steingräber: 14 probes: types and their indications (2014) . onkodin.de. Retrieved February 22, 2019.

- ↑ Michael de Ridder: Medicine at the end of life: tube feeding rarely increases the quality of life . In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt . tape 105 , no. 9 , 2008 ( aerzteblatt.de ).

- ^ J McCue: The naturalness of dying . In: JAMA . tape 273 , 1995.

- ↑ M Synofzik: PEG nutrition in advanced dementia . In: Neurologist . tape 78 , 2007.

- ↑ a b c Anika Rosenbaum, Jürgen F. Riemann, Dieter Schilling: The percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG). Dtsch med Wochenschr 2015; 140 (14): 1072-1076 ; accessed on February 22, 2019

- ^ A b Claudia Bausewein , Susanne Roller and Raymond Voltz (eds.): Guide to Palliative Care. Palliative Medicine and Hospice Care. Elsevier Munich, 5th edition 2015, p. 179

- ↑ Transnasal probes and accessories . Nutricia.

- ↑ Andrea Arnoldy: Percutaneous Endoscopic gastrostomy . Button - advantages and disadvantages compared to the classic PEG ( uk-essen.de [PDF]).

- ↑ Thomas Heinemann, Klaus Herz, Andrea Tokarski, Luise Scholand, Gerhard Robbers: Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) and jejunostomy (PEJ) - internal ethical guideline for the ctt . Ed .: Cusanus Trägergesellschaft. Trier ( ethikkomitee.de [PDF]): “The simple installation and maintenance of the PEG / PEJ tube as well as the enteral feeding can lead to a generous application of the procedure, which, on critical examination, raises questions about its justification. When deciding to use a PEG / PEJ probe, medical, nutritional, nursing, ethical and legal issues must be taken into account "

- ^ Daniela Müller-Gerbes: PEG probe - medical experts . ( leading-medicine-guide.de ): "Otherwise, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) is subject to the same risks as a gastroscopy."

- ↑ Tobias Stefan Finzel: Retrospective investigation of the laxative behavior of critically ill patients with acute cerebral damage .

- ↑ Tobias Stefan Finzel: The use of long-term tube feeding in people with dementia in inpatient long-term care .

- ↑ Tube feeding at home, company publication: Nutricia item number 9796010, as of 09.15

- ↑ Nina Fleischmann, Steve Strupeit: Norderstedt (Hrsg.): Bremen contributions to professional education, clinical nursing expertise and family and health care 2009, ISBN 9783837051452 . .

- ↑ a b Guideline for the care of a balloon tube after direct puncture . Fresenius Kabi.

- ↑ G. Fetzer-Mütz (endoscopy team, coordinator cancer center, health association district Konstanz): Supply of a PEG system - standard of care / patient information. Status: 2017 ; accessed on February 22, 2019

- ↑ Ciocon JO, Silverstone FA, Graver LM et al .: Tube feeding in elderly patients. Indications, benefits, and complications. Arch Intern Med 1988; 148: 429-33.

- ↑ DGEM guidelines . Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ↑ Constanze Schäfer (Ed.): Probe application of drugs. Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft, Stuttgart 2010, pp. 21–23

- ↑ a b Fresenius guideline drug administration via probe

- ↑ Vera Voigt and Thomas Reinbold: What to watch out for with probes - What to do if the probe is blocked? . Retrieved November 7, 2016.

- ↑ Dunitz-Scheer, M., Huber-Zyringer, A., Kaimbacher, P., Beckenbach, H., Kratky, E., Hauer, A. et al .: Tube weaning. In: Pädiatrie, 4 + 5, 2010, pp. 7–13.

- ↑ Thomas Reinehr: Pediatric nutritional medicine: Basics and practical application . Ed .: Georg Thieme Verlag. Stuttgart New York 2012, ISBN 3-7945-2794-1 .

- ↑ BGH: BGH Decision of June 8, 2005 Az. XII ZR 177/03 . In: New legal weekly . 2005, p. 2385 .

- ↑ F. Oehmichen et al .: Guideline of the German Society for Nutritional Medicine (DGEM). Ethical and legal aspects of artificial nutrition. In: Current Nutritional Medicine 2013; 38; P. 114 (4.2 Artificial nutrition can make care easier. ) ; accessed on February 22, 2019

other remarks

- ↑ With the balloon probe (medical technology) , a second tube is required to fill the holding balloon, which is guided in the main tube.

- ↑ 1,000 ml should be administered in 8 hours (Nutricia "Gut zu Wissen", p. 18)

- ↑ Basal metabolic rate of older people: 20–30 kcal / kg body weight, with underweight –38 kcal / kg body weight (Nutricia "Good to know", p. 12)

- ↑ The supply hose must always be rinsed after each use

- ↑ - determine the cause, - hose ?, - which substance last?

- ↑ Because of the potential for quick closure, however, if the removal was unintentional , quick action is required.