Imperial Fleet

The first all-German navy in German naval history is called the Reichsflotte . It was founded on June 14, 1848 by the National Assembly in Frankfurt am Main . As a German naval force, it was intended to protect German merchant ships in general and specifically to serve in the Schleswig-Holstein war against Denmark . The German central authority worked closely with the German coastal states and the Provisional Government of Schleswig-Holstein . Prince Adalbert of Prussia , who was considered a naval expert and also advised Prussia , was involved in the plans .

In the short period of 1848/1849 it was possible to buy and convert a small number of ships. In the war against Denmark, however, the imperial fleet was hardly used at all. After the suppression of the German Revolution, the Reichsflotte was transferred to the restored German Confederation by way of the Federal Central Commission .

There were plans to continue and expand the fleet as a federal fleet, but ultimately neither the German federal government nor a member state wanted to bear the costs. In addition to the question of costs, the reason for this was the end of the war between Germany and Denmark: A German fleet was no longer needed immediately. In 1852/53, Federal Commissioner Laurenz Hannibal Fischer sold the ships.

Later the North German Confederation built its own naval forces, which became the basis of today's German Navy . In memory of the fleet resolution in the Frankfurt National Assembly in 1848, this celebrates June 14th as the day of its foundation.

Designations

Several names were used for the German Navy as an overall organization and the fleet as a summary of the naval warfare of that time. The decision of the National Assembly of June 14, 1848 speaks simply of the " German Navy ". Navy Minister Arnold Duckwitz wrote a report in 1849 about "the establishment of the German Navy ". The certificate of appointment for Admiral Bromme again reads " Reichs-Marine ". The protocols of the Reich Ministry (the government) alternately use the terms Reichsflotte and Reichsmarine , but neither the Kriegsmarine nor the Federal Navy or the Federal Fleet . Article 19 of the Imperial Constitution says “Navy”.

The term Reichsflotte has become common in historical science . This distinguishes them from the Imperial Navy of the Weimar Republic (1919–1933). The terms Bundesmarine and Bundesflotte , which one finds in the later literature in places, are rather unsuitable . At least when it was founded, it was not the Navy of the German Confederation . In addition, in 1865 there was an Austro-Prussian plan for a “ federal fleet ”.

Starting position

Nationalism and liberalism shaped not only the debates in the Frankfurt National Assembly, but also those in other countries. The Frankfurt navalism, on the other hand, was of its own kind: It came from the pain that the German territories had to endure the battles of foreign powers for centuries; The resulting desire for national power led, in a strange way, to enthusiasm for the fleet, according to Wolfgang Petter. This may have been due to the liberals' aversion to the land military, which supported absolutism and then the conservatives.

In practice, German traders and travelers experienced that the Mediterranean and the Central Atlantic were very dangerous for ships flying a German flag. For example, barbarian states in northwest Africa waged a pirate war against the Christian world. States without a powerful navy should pay, which made trade from insurance costs very expensive. Even if the danger was largely a thing of the past in the 1840s, partly because of the conquest of Algeria by France in 1830, the memory of "the great time of piracy only from the helpless Germans" lived long afterwards. A newspaper article complained that the German merchant ships were lying "defenseless and unarmed like fat carp under sharp-toothed pike and sharks" because the German people had failed to forge a trident for the German Neptune.

But also regular fleets of other powers endangered German merchant ships; When Prussia annexed Hanover in 1805, England captured almost the entire Prussian merchant fleet. German traders were also a thorn in the side of the Danish sound tariff that had to be paid to get from the North Sea to the Baltic Sea and vice versa. Great Britain tolerated this, among other things because it indirectly earned from it itself (the duty was partly pledged to London bankers). The German liberal Friedrich List, for example, evoked a far-reaching positive response when he proposed a tariff war against the “northern predatory state” Denmark.

Fleets of German states before 1848

The founding acts and treaties of the German Confederation knew no navy. Although there were important ports in Hamburg, Bremen and Lübeck and also in Prussia, the German merchant fleets were without military protection from a sea power. It was partly believed that foreign federal members could provide protection: Until 1837 Hanover was linked to Great Britain in a personal union. In 1845, the Prussian king even proposed (unsuccessfully) his Danish colleague to become Germany's Grand Admiral . Of the German states, only Austria, which had once taken over from the Republic of Venice , had a significant, albeit second-rate, fleet .

The Austrian Navy was stationed in the Mediterranean ports of Venice and Trieste . Most of their crews were of Italian origin and defected to the enemy in the course of the independence struggle in Veneto in 1848, with some ships also being transferred. The ships that remained in Austrian hands were needed for naval warfare in the Adriatic . Despite the war against Denmark, the search for a suitable commander for the rebuilding of the navy did not hesitate to select the Danish commodore Hans Birch Dahlerup for this position. Against this background, the Austrian Navy was not available for the war against Denmark.

Shortly before the March Revolution, Prussia had already endeavored to persuade other German North Sea residents to adopt a common trade policy; a war fleet was one of the ideas. The Prussian Prince Adalbert had proposed a “sea defense” consisting of row cannon boats. However, he met with great resistance, because a fleet was associated with high costs. It was not seen as necessary for actual national defense, and the Prussian king would have had to set up the long-promised constitution with parliament (national representation) for the necessary government loan.

To protect its growing maritime trade , Prussia relied on the other federal princes with their naval forces. Since the mid-1830s there have been various initiatives to build up our own naval forces , which until 1848 only led to the equipping of a single school corvette, the Amazon . In addition, the ships of the state shipping company Prussian Sea Handling were armed and carried the Prussian naval flag.

Outbreak of the revolution and war with Denmark in 1848

The Danish king was duke of both the German-speaking Holstein, which was also a member of the German Confederation, and the mixed-language Schleswig. In the spring of 1848 there was a conflict between German-speaking and Danish national movements. In the uprising of the German movement against Denmark , a provisional government and Schleswig-Holstein's own army were formed . Individual German states supported the German Schleswig-Holsteiners militarily against the Danish army . The German Confederation declared the Federal War against Denmark.

However, the war made it abundantly clear how vulnerable German merchant ships and German coastal ports were. On April 14, 1848, Denmark confiscated Prussian ships in large numbers for the first time. Austria remained de facto neutral and could not have intervened at all: many of its Mediterranean ships were stranded in the blocked port of Trieste, or their crews had defected to the Italians. In almost all the larger German cities, naval associations and committees were formed that collected money for a German fleet.

After the outbreak of the March Revolution in 1848, the pre-parliament first dealt with the problem. This meeting of German state parliamentarians called on the Bundestag, the coastal states and the German people to form a navy. On April 15, 1848, the Bundestag's Committee of Seventeen called on the Bundestag to initiate appropriate measures. Three days later the Bundestag set up a naval committee consisting of the envoys from Prussia, Hanover, Mecklenburg, Oldenburg, Hamburg, Bremen and Lübeck.

The Fifties Committee of the Pre-Parliament asked the Bundestag to purchase warships and build defensive structures on the coasts. The Bundestag accepted the request, while the coastal states were already improving their coastal defense. Numerous private initiatives in Germany passionately joined the call for a German naval power and began to raise money. On May 31, 1848, the German Naval Congress in Hamburg asked the National Assembly to establish a naval ministry for the purpose of establishing the fleet.

National naval forces from 1848

In a first reaction, the northern German coastal states agreed to arm merchant ships and to upgrade them to warships under the leadership of the so-called Hamburg Committee . In addition, were gunboats built. The British naval officer Hammel Ingold Strutt was recruited as commander and set in the rank of frigate captain . On June 23, 1848, the Hamburg Admiralty bought these ships, which were financed from donations, for the imperial fleet that was to be built up. This flotilla , under Hamburg leadership , thus became the foundation of the imperial fleet.

At the same time, the establishment of its own small navy began with all the components of a naval force in Schleswig-Holstein. This Schleswig-Holstein Navy , which at times had 16 ships and vehicles, fought in the North and Baltic Seas against the superior Danish Navy . The Schleswig-Holstein Navy only formally submitted to the Reichsflotte, but its ships carried its black, red and gold flag.

Prussia not only saw itself exposed to threats to its merchant shipping, but also feared that Russia might join the war on the Danish side. Therefore, the considerations to build up your own navy were accelerated. As a first measure, 40 rowing cannon boats were built, which remained in service until 1870.

German Empire 1848/1849

Like the Bundestag, the National Assembly also founded a naval committee on May 26, 1848. It included the Austrian Karl Ludwig von Bruck , the Prussian general Joseph von Radowitz and the Hamburg shipowner and businessman Edgar Roß, who was later replaced by Ernst Merck . As early as June 8th, Radowitz from the extreme right presented a report from the committee. The committee should define the functions of the fleet and, after an analysis, present a step-by-step plan for the construction of ships. The committee demanded six million thalers for an immediate first construction phase. The German fleet will be an internal and external sign of German unification:

“The first German warship that appears and lies in front of the mouth of the Rio de la Plata shows the numerous Germans there that they no longer depend exclusively on the arbitrariness of a tyrant, but that behind them there is a people of forty million. (Continuing Bravo) […] The creation of the fleet is not just a military question, a commercial question, but to the highest degree a national question. "

Despite some reservations about deciding on something concrete without fully developed plans and burdening the population financially after the previous economic crisis, the National Assembly accepted the proposals of the Navy Committee on June 14th. Both left, center and right were almost unanimously behind the decision. The delegates spoke of the elimination of the Sundzolls, the war over Schleswig and Holstein, the possibilities of a colonial policy, the promotion of overseas trade and the economy and, in general, of national honor; some also presented special local interests.

Six million thalers should be made available for the fleet. However, at that time there was still no all-German executive. This only received its legal basis on June 28, 1848, with the Reich Law on Provisional Central Authority . It was the task of the central authority with its Reich administrator and the Reich ministers to ensure the "security and welfare of the German federal state".

Following the considerations of the time, the Reichsmarine should act on the high seas and protect Prussia the coasts. According to Prince Adalbert, there were three types of fleets: one for the defense of coasts, one for offensive defense and the protection of trade, and an "independent sea power". These became the guiding principles of the imperial fleet policy; In realizing the first stages, the last one should be kept in mind, including the risk that other powers intervened in the meantime. It was now expected that the implementation would take much longer than in previous plans, although the armistice with Denmark would soon expire.

State support

But on September 29, Reich Finance Minister Hermann von Beckerath reported to the MPs that there was no money for big plans. In June Parliament had decided on a sum to be collected from the individual states, but this had not yet happened; the received donations of 73,000 guilders were invested to earn interest; There were still no worthwhile projects. A month later, Reich Minister of Commerce Arnold Duckwitz , who was now also responsible for the Navy, had to start all over again.

In the first half of the year, the German Confederation had reserved 520,000 guilders for the fleet, which were actually intended for the fortresses in Rastatt and Ulm. For the year 1848, the individual states usually paid the federal and then the Reich registers for joint military expenditures; Bavaria , Saxony , Kurhessen and Luxembourg - Limburg were partly behind . By the end of 1849, naval expenditures had risen to three times the original 520,000 guilders, and by March 1, 1850, nearly 1.8 million guilders were missing from state naval contributions. Only Prussia , Hanover , Holstein , Lauenburg , Mecklenburg-Schwerin , Nassau , Oldenburg , Anhalt-Dessau , Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt , Waldeck and the four Free Cities had paid in full . The Federal Central Commission had accepted that Austria paid less because of its expenses for the Mediterranean fleet.

Otherwise Prussia, including the king, helped build the imperial fleet; for example, the king approved the leave of Prince Adalbert. Prussian officers supervised a gun foundry in Hanover that had delivered poor quality. Like Prussia, Hanover also had the material for the Imperial Fleet transported free of charge and without a transit toll across its territory.

Cooperation with the USA

In October 1848 the central authority asked the USA for a naval officer to be in command of the imperial fleet. President James K. Polk replied that he would have to ask Congress for approval, but he could give leave to someone to look into the matter. In December Commodore Foxhall A. Parker then traveled to Europe and inspected docks in Bremen, among other things. At the time of his trip, however, the counter-revolution had already started; he did not find a real fleet either. He decided not to take up German service and advised other American officers against it.

In the meantime, the German envoy in Washington, Friedrich von Rönne , made copies of American naval laws and regulations and sent them to Frankfurt with all sorts of other information that could be useful for building up the fleet. In February 1849, he asked the American Secretary of State that the central government could buy a steamer frigate in the United States. This should be equipped under the supervision of an American officer and transferred to Germany.

The Secretary of State appointed Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry and directed the Brooklyn Navy Yard to provide any assistance. A parcel boat was then bought and made ready. But soon afterwards, the new President Zachary Taylor withdrew support because he was concerned about American neutrality. Denmark had protested, so Germany had to promise the US that it would not use the ship against Denmark. The Malmo Treaty was, after all , just a truce, not a peace treaty.

Navy of the German Empire

Reich Ministry of the Navy

The Reich Ministry of the Interior was initially responsible for setting up a navy in the central government. In the Council of Ministers, Interior Minister Anton von Schmerling handled the naval issues. The establishment of an independent naval ministry was considered at an early stage, but made dependent on the existence of a suitable manager. According to the minutes of the Council of Ministers of August 29, 1848, the minister of war Eduard von Peucker resisted the task of and personal responsibility for the Reichsflotte, depending on the personality of the minister or the undersecretary or technical director in an existing ministry .

By the beginning of November, the entire Reich Ministry (the government) agreed to set up a “provisional central authority for the German Navy”, which the Reich Administrator carried out by decree on November 15, 1848. The new authority consisted of a "Department for the Navy Administration" and a "Technical Marine Commission". It was affiliated to the Reich Ministry of Commerce, which was already entrusted with questions of civil shipping. Trade Minister Arnold Duckwitz reported in his memoirs that no minister wanted to take over the navy during the October deliberations: nobody understood anything about it. In the end Duckwitz complied because, in the opinion of the other ministers, he knew more about maritime affairs than they did. The naval ministry was subordinate to three naval authorities: the high command, the naval master's office and the general manager. There was also a court martial known as a naval auditor.

After the end of the Frankfurt National Assembly in May 1849, the Austrian Lieutenant Field Marshal and Reich Foreign Minister August von Jochmus became Minister of the Navy. The navy was given its own ministry. In fact, it was headed by the Reich Finance Minister Ernst Merck for the last six months, who increased the number of ships.

Prince Adalbert of Prussia was in Frankfurt from 1848 to February 1849 the Technical Naval Commission in the naval department. The commission dealt with the acquisition, construction and conversion of warships, their arming and stationing. The question of a canal between the North Sea and the Baltic Sea was also considered. She was also responsible for human resources and budget matters. After Adalbert's recall by the King of Prussia, the then frigate captain Karl Rudolf Bromme , known as Brommy , took over this task.

Supreme command and staff

According to the Reich constitution, all German naval forces should have been subordinate to the Reich Ministry of the Navy. However, that happened neither for the Prussian Navy, which was being established, nor for the Austrian Navy. Although the Schleswig-Holstein Navy was formally subordinated to the Reichsflotte on April 26, 1849, it operated independently of it. Only the ships of the Hamburg Flotilla were taken over by the Reichsflotte and incorporated into its inventory. These included the steam corvettes Bremen , Hamburg , Lübeck and the sailing corvette Franklin .

The British frigate captain Strutt was initially charged with the supreme command. He had been taken over from the Hamburg service. On April 5, 1849, Brommy took over the job. Supreme command, naval shipbuilding, command and administration were united on this occasion, with headquarters, armed forces, shipyards and arsenals in Bremerhaven . Brommy received the title of Commander-in-Chief of the North Sea Fleet and Sea Master for the North Sea and was promoted to Captain of the Sea . In the same capacity he was promoted to commodore on August 19 and to rear admiral on November 23, 1849 .

Because the German states had hardly any naval forces of their own, the personnel had to be recruited from foreign navies and merchant shipping. Leading German officers like Brommy and Donner had served in foreign navies. There were also foreign officers, mainly from Belgium and Great Britain.

In the summer of 1850 the Reichsflotte had about 1000 active members, including 60 naval officers, 48 officer cadets, 8 doctors, 30 officers from the naval master craftsman's office and paymaster's office, 30 machinists, 700 non-commissioned officers and sailors and 100 marines. To train the officer candidates, the frigate Germany served as a training ship and naval school. The Reichsflotte also included a marine infantry , the Reichs-Marinier-Corps , which were intended for service on warships and for guard duties on land. His strength should not have exceeded that of a company .

Ships and land facilities

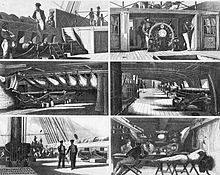

Without the forces under the sovereignty of the states, the fleet consisted of two sailing frigates, three steam frigates, six steam corvettes and over two dozen row-cannon boats until 1852 . Only the frigate Eckernförde was built as a warship. This Danish frigate Gefion fell into German hands in the battle near Eckernförde in 1849. All other ships were converted merchant ships. The flagship for Admiral Brommy was initially the wheel frigate Hansa , which had been bought in America, and later the Barbarossa .

Contrary to popular belief, according to Walther Hubatsch, Great Britain was not fundamentally against a German fleet. Although the British government had not formally recognized the German, it allowed Prince Adalbert to visit British shipyards and naval facilities for the central authority in November 1848. Half of the German ships had been bought in Great Britain; they were first-class, modern ships.

Gustav Winkler from Halberstadt proposed to the Prussian government that they design a submarine. It was supposed to attack and sink enemy ships underwater without being noticed. On September 11, 1848, the offer was before the Naval Committee of the National Assembly. The six-meter-long boat would have been powered by a steam engine and would have attached an explosive device to the bottom of the enemy ship, which was supposed to be detonated by wire. Due to a lack of money, not even an experimental building was built. With private funds, the engineer Wilhelm Bauer then built another submarine, the fire diver . This sank to the bottom of the Kiel Fjord during a training run in 1851.

The imperial fleet relied primarily on ports in the Weser region. This included the so-called Seezeugmeisterei in Bremerhaven , where the command and administrative authorities of the navy were located. Several states competed to build naval ports, including Bremen, Hanover, Oldenburg and Prussia. Oldenburg offered to build a permanent base and winter port on the Jade , where Wilhelmshaven was later established as the main base for German navies on the North Sea. However, Brommy preferred Brake as a temporary further base. From 1848, dock facilities were built there to support and repair the fleet. The fleet spent the winter of 1848/49 divided between Brake and Bremerhaven.

During the war against Denmark, numerous coastal batteries were set up along the North Sea coast, which also belonged to the area of responsibility of the Reich Ministry of the Navy. However, they were often under the command of the respective German individual states.

commitment

The Reichsflotte came to its first and only combat mission in the naval battle off Heligoland on June 4, 1849, the only naval battle under the black, red and gold flag to date . The flagship on this mission was the steam frigate SMS Barbarossa under Brommy, who was chasing a Danish ship coming from the Weser. Before Heligoland , the Germans got into British territorial waters. The British did not recognize the German flag and gave a warning shot, and another Danish ship was added. Brommy feared more ships would arrive, so he withdrew.

The "well trained and fully operational" naval forces of the Reichsflotte, according to Walther Hubatsch, were largely forced to inactive because Great Britain and Russia protected Denmark in order to preserve the status quo at the Baltic Sea exits. The German Bundestag (which had adopted black, red and gold on March 9, 1848) and then the central power had failed to formally display the new flag abroad. With some justification, Great Britain used this formal oversight as a pretext to warn that ships flying an unknown flag were unprotected under international law. In 1849/1850 the Federal Central Commission caught up on the complaint.

But Great Britain and Russia still did not recognize the German colors and thus prevented the imperial fleet from being transferred from the Weser to the bases in Wismar and Swinoujscie. Hanover and the central authority negotiated until the contract was ready for Hanover to take over the fleet as the largest North Sea state. But on September 17, 1849, the King of Hanover backed down because the end of central power in its former form was foreseeable, and Hanover was afraid of having to pay for the maintenance costs of a considerable fleet alone. After all, Denmark was no longer at war and the blockade was lifted.

The fleet after the end of the revolution

Course of the year 1849

Prince Adalbert left Frankfurt in February 1849 and took over the supreme command of the Prussian Navy in May 1849. He urged the Kingdom of Prussia (ruled from 1840 to 1861 by Friedrich Wilhelm IV. ) To take on the role of German naval power itself. On March 28, 1849, the National Assembly put the Frankfurt Constitution into effect. Because of the sometimes violent resistance of the large individual states, this constitution was not effective. In Article III § 19 it dealt extensively with the fleet:

- [1] Sea power is the exclusive responsibility of the empire. No state is permitted to keep warships for itself or to issue letters of piracy.

- [2] The manning of the navy forms part of the German Wehrmacht. It is independent of land power.

- [3] The team that is provided for the navy from a single state is to be deducted from the number of land troops to be held by the same. The details about this, as well as about the equalization of costs between the Reich and the individual states, are determined by a Reich law.

- [4] The appointment of the officers and officials of the sea power comes from the Reich alone.

- [5] The imperial power is responsible for the equipment, training and maintenance of the navy and the establishment, equipment and maintenance of war ports and sea arsenals.

- [6] The imperial laws to be enacted determine the expropriations necessary for the establishment of war ports and naval establishments, as well as the powers of the imperial authorities to be employed.

Despite the end of the National Assembly in May 1849, the plans of the Navy Ministry, under Reich Foreign Minister Jochmus , continued, as more than 670 ship drawings and plans in the Navy Ministry show. The Federal Central Commission of Austria and Prussia, which assumed the tasks of central power, set up a naval department. Since January 31, 1850, this institution has been under the command of the Navy and the Naval Inspectorate with a subordinate naval directorate.

Plans in the German Confederation

During the Dresden Conferences of 1850/1851, which finally led to the restoration of the German Confederation, no state wanted to take over the imperial fleet. It was expensive, considered a child of the revolution, and had hardly any military value. Because of its matriculation payments, Prussia considered itself the main creditor and wanted to see the ships sold quickly. When the Bundestag met again, Austria adopted a wait-and-see attitude. Prussia, however, complained that the federal government appropriated the fleet because, from the Prussian point of view, it was a German fleet, but never a federal fleet. It was also against the fact that a majority in the Bundestag approved 532,000 guilders for maintaining the fleet in the current year.

Austria presented that the Baltic Sea Fleet of Prussia, the Adriatic Fleet of Austria and the North Sea Fleet of a common navy of the medium-sized states could together form a federal fleet, analogous to the federal troops. The Austrian trade minister Freiherr von Bruck hoped to encourage the medium-sized states to adopt their own trade policy and thereby weaken Prussia's trade and customs union policy. When this was unsuccessful, Austria itself pushed for the liquidation of the fleet. In 1852 the German Federation auctioned the remaining ships.

Dissolution in 1852/1853

The Bundestag decided to dissolve the fleet and sell the ships if an association of states was not formed by March 31, 1852, which took over the fleet as the third contingent of a federal fleet. The basis for the actual resolution to dissolve on April 2 was the view that the fleet was only federal property, but not an “organic federal facility” (Article 7 of the Federal Act). That meant that a simple majority vote was enough. Hannover filed for legal custody because, in its opinion, the fleet was such an institution, so that the dissolution would have required a unanimous decision.

The background to the different views was the question of whether the German Empire of 1848/1849 was identical to the German Confederation. The German governments had initially been of this opinion in 1848 in order to steer the revolution in an orderly manner. Then the fleet, as a Reich institution, would also have been a federal institution. However, if the Reich was viewed as a new creation of the revolution, as the National Assembly did in 1848 (and, after the revolution was suppressed in 1849, so did the German governments that were again conservative), the imperial fleet had come to the Confederation as mere property.

“The eventual dissolution of a facility for which there was no longer any need was an act of economic reason that cannot be criticized,” says Walther Hubatsch. Laurenz Hannibal Fischer , formerly President of the Oldenburg government of the Principality of Birkenfeld , as Federal Commissioner had to sell the fleet and its facilities as well as accept the creditors and the crews. Before he came to Bremerhaven, he suspected that the ships there were “breeding grounds for radicalism”. Indeed, he found orderly, disciplined associations. As a supporter of the naval endeavors, he was reluctant to dissolve it, but it was correct and timely, for which the Bundestag thanked him in March 1853.

outlook

Prussia took over Eckernförde and Barbarossa from the Reichsflotte and has been expanding its fleet since the 1860s. The German Confederation still had no naval forces. In the German-Danish War of 1864 Prussian and Austrian ships were used, but the two naval battles of the war were of little importance. In 1865 Austria and Prussia agreed to campaign for a fleet of the German Confederation . This did not happen because of the Austro-Prussian conflict and the dissolution of the German Confederation .

The North German Confederation of 1867 created its own navy , which, however, remained relatively small. In the naval war during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71 there were isolated encounters between North German and French ships. The decisive battles, however, took place in the countryside. It was not until the Imperial Navy (from 1871) that a large fleet built up over the years.

See also

literature

- Jörg Duppler : Germania on the sea. Pictures and documents on German naval history 1848–1998. Mittler, Hamburg et al. 1998, ISBN 3-8132-0564-9 (volume accompanying the exhibition "Pictures and documents on German naval history 1848–1998", Lüneburg 1998).

- Rolf Güth: From revolution to revolution. Developments and leadership problems of the German Navy 1848/1918. Mittler, Herford 1978, ISBN 3-8132-0009-4 .

- Walther Hubatsch , Hanswilly Bernartz , Klaus Friedland, Peter Galperin, Paul Heinsius, Arnold Kludas : The first German fleet 1848–1853 (= German Navy Academy. Series of publications. 1). Mittler, Herford et al. 1981, ISBN 3-8132-0124-4 . *

- Rolf Noeske / Claus P. Stefanski: The German Marines 1818-1918. Organization, uniforms, armament and equipment , 2 volumes, Vienna (Verlag Militaria) 2011. ISBN 978-3-902526-45-8

- Wolfgang Petter: Programmed downfall. The defective armament of the German fleet of 1848. In: Michael Salewski (Ed.): The Germans and the Revolution. 17 lectures for the Ranke Society. Muster-Schmidt, Göttingen et al. 1984, ISBN 3-7881-1738-9 , pp. 228-256, (as well as in: Military History Research Office (ed.): Military history. Problems - theses - ways (= contributions to military and war history. 25). Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1982, ISBN 3-421-06122-X , pp. 150-170).

- Michael Salewski : The "Reichsflotte" from 1848: Your place in history. In: sheets for German national history . 126, 1990, pp. 103-122, ( digitized version ).

- Guntram Schulze-Wegener : Germany at sea. Illustrated naval history from the beginning to the present day. Preface by Wolfgang Nolting, introduction by Heinrich Walle . 2nd, completely revised and expanded edition. Mittler, Hamburg 2007, ISBN 978-3-8132-0885-6 .

- Wolfgang Meironke: The history of the first German fleet under the colors black-red-gold (1848 to 1853). With special consideration of the life of Carl Rudolph Brommy (1804-1860), the first German admiral , Frankfurt / Main (RG Fischer Verlag) 2020. ISBN 978-3-8301-9653-2

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ On the question of the designation, see above all: Walther Hubatsch (Ed.): The first German fleet 1848–1853 . ES Mittler and Son, Herford / Bonn 1981, ISBN 3-8132-0124-4 ; there in particular the articles by Walther Hubatsch, Die deutsche Reichsflotte 1848 and der Deutsche Bund , pp. 29 ff .; Paul Heinsius, The First German Navy in Tradition and Reality , p. 73 ff. And Walther Hubatsch, Research Status and Results , p. 79 ff. (82 ff.).

- ^ Federal archive / military archive inventory DB 52 / 1-17, minutes of the Reichsministerrat meeting with enclosures .

- ↑ Wolfgang Petter: The overseas base policy of the Prussian-German navy 1859-1883 . Dissertation Freiburg i. Br. 1975, p. 13.

- ↑ Wolfgang Petter: The overseas base policy of the Prussian-German navy 1859-1883 . Dissertation Freiburg i. Br. 1975, pp. 14-16.

- ^ Günter Wollstein: The 'Greater Germany' of the Paulskirche. National goals in the bourgeois revolution of 1848/1849. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 256.

- ↑ Wolfgang Petter: The overseas base policy of the Prussian-German navy 1859-1883 . Dissertation Freiburg i. Br. 1975, pp. 16-18.

- ↑ Lawrence Sondhaus: Central Europe to sea? Austria and the German Navy Question 1848-52 . In: Central European History , Volume 20, No. 2 (June 1987), pp. 125-144, here pp. 126/127.

- ↑ Wolfgang Petter: The overseas base policy of the Prussian-German navy 1859-1883 . Dissertation Freiburg i. Br. 1975, pp. 19/20.

- ↑ Wolfgang Petter: The overseas base policy of the Prussian-German navy 1859-1883 . Dissertation Freiburg i. Br. 1975, pp. 21/22.

- ^ Günter Wollstein: The 'Greater Germany' of the Paulskirche. National goals in the bourgeois revolution of 1848/1849. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, pp. 258/259.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1960, pp. 656/657.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1960, p. 657.

- ↑ a b c d Lecture at the Maritime Museum Brake ( Memento of the original from September 17, 2004 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b Guntram Schulze-Wegener: Germany at sea. 150 years of naval history. Mittler, Hamburg 1998. ISBN 3-8132-0551-7

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [ua] 1960, p. 657.

- ^ Günter Wollstein: The 'Greater Germany' of the Paulskirche. National goals in the bourgeois revolution of 1848/1849. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, pp. 261/262.

- ^ Günter Wollstein: The 'Greater Germany' of the Paulskirche. National goals in the bourgeois revolution of 1848/1849. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, pp. 262/263.

- ↑ Wolfgang Petter: The overseas base policy of the Prussian-German navy 1859-1883 . Dissertation Freiburg i. Br. 1975, p. 21.

- ^ Günter Wollstein: The 'Greater Germany' of the Paulskirche. National goals in the bourgeois revolution of 1848/1849. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 265.

- ^ Günter Wollstein: The 'Greater Germany' of the Paulskirche. National goals in the bourgeois revolution of 1848/1849. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 264.

- ^ Walther Hubatsch: The German Reichsflotte 1848 and the German Confederation. In: ders. (Ed.): The first German fleet 1848–1853 , ES Mittler and Son, Herford / Bonn 1981, pp. 29–50, here pp. 37/38.

- ^ Walther Hubatsch: The German Reichsflotte 1848 and the German Confederation. In: ders. (Ed.): The first German fleet 1848–1853 , ES Mittler und Sohn, Herford / Bonn 1981, pp. 29–50, here p. 36.

- ^ Henry M. Adams: Prussian-American Relations, 1775-1871 . Press of Western Reserve University, Cleveland 1960, p. 62.

- ↑ Lawrence Sondhaus: Naval Warfare, 1815-1914. Routledge, London 2001, p. 49.

- ^ Henry M. Adams: Prussian-American Relations, 1775-1871 . Press of Western Reserve University, Cleveland 1960, p. 62.

- ^ Henry M. Adams: Prussian-American Relations, 1775-1871 . Press of Western Reserve University, Cleveland 1960, p. 62.

- ↑ John Gerow Gazley: American Opinion of German Unification, 1848-1871 . Diss. Columbia University, New York 1926, pp. 25/26.

- ^ Ralf Heikaus: The first months of the provisional central authority for Germany (July to December 1848). Dissertation Frankfurt am Main, Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main [a. a.] 1997, pp. 114/115, footnote 262.

- ^ Ralf Heikaus: The first months of the provisional central authority for Germany (July to December 1848). Diss. Frankfurt am Main, Peter Lang, Frankfurt a. M. [u. a.] 1997, p. 115, footnote 262.

- ^ Federal archive / military archive inventory DB 64 I, naval authorities .

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1960, p. 659.

- ↑ Transfer documents in the Federal Archives (holdings DB 59/121 and 59/122) ( Memento of the original from January 15, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ^ Walther Hubatsch: The German Reichsflotte 1848 and the German Confederation. In: ders. (Ed.): The first German fleet 1848–1853 , ES Mittler und Sohn, Herford / Bonn 1981, pp. 29–50, here p. 39.

- ↑ List of officers in the Federal Archives ( Memento of the original from October 18, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 55 kB)

- ^ Walther Hubatsch: Research status and result. In: ders. (Ed.): The first German fleet 1848–1853 , ES Mittler and Son, Herford / Bonn 1981, pp. 79–94, here pp. 88/89.

- ↑ Walther Hubatsch: The exchange ship - the first German submarine design . In: ders. (Ed.): The first German fleet 1848–1853 , ES Mittler und Sohn, Herford / Bonn 1981, p. 78.

- ^ Walther Hubatsch: Research status and result. In: ders. (Ed.): The first German fleet 1848–1853 , ES Mittler and Son, Herford / Bonn 1981, pp. 79–94, here pp. 86/87.

- ^ Walther Hubatsch: Research status and result. In: ders. (Ed.): The first German fleet 1848–1853 , ES Mittler and Son, Herford / Bonn 1981, pp. 79–94, here pp. 87/88.

- ↑ Lawrence Sondhaus: Naval Warfare, 1815-1914. Routledge, London 2001, p. 49.

- ↑ Wolfgang Petter: The overseas base policy of the Prussian-German navy 1859-1883 . Dissertation Freiburg i. Br. 1975, pp. 20/21.

- ^ Walther Hubatsch: Research status and result. In: ders. (Ed.): The first German fleet 1848–1853 , ES Mittler and Son, Herford / Bonn 1981, pp. 79–94, here pp. 84/85.

- ↑ Wolfgang Petter: The overseas base policy of the Prussian-German navy 1859-1883 . Dissertation Freiburg i. Br. 1975, pp. 23/24.

- ↑ Lawrence Sondhaus: Central Europe to sea? Austria and the German Navy Question 1848-52 . In: Central European History , Volume 20, No. 2 (June 1987), pp. 125-144, here p. 137.

- ↑ Wolfgang Petter: The overseas base policy of the Prussian-German navy 1859-1883 . Dissertation Freiburg i. Br. 1975, pp. 24/25.

- ^ Frank Lorenz Müller: The revolution of 1848/1849. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2002, p. 91.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, pp. 138-140.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, pp. 141-143.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 141.

- ^ Walther Hubatsch: Research status and result. In: ders. (Ed.): The first German fleet 1848–1853 , ES Mittler and Son, Herford / Bonn 1981, pp. 79–94, here pp. 90/91.