Richard III (England)

Richard III (* October 2, 1452 at Fotheringhay Castle , Northamptonshire ; † August 22, 1485 at Market Bosworth , Leicestershire ) was King of England from 1483 until his death in the Battle of Bosworth . He was the last English ruler from the House of Plantagenet and at the same time the last to fall on a battlefield. With his death, the era of the so-called Wars of the Roses ended , in which two branches of the Plantagenets, the houses York and Lancaster, fought a decades-long power struggle against each other.

In 1597 Shakespeare wrote the drama The Tragedy of King Richard III. , which has partly influenced Richard's image negatively to this day. During a targeted excavation in Leicester in September 2012, bones were found which, with the help of DNA analyzes, were unequivocally identified as the Richards III in February 2013. could be identified.

Life

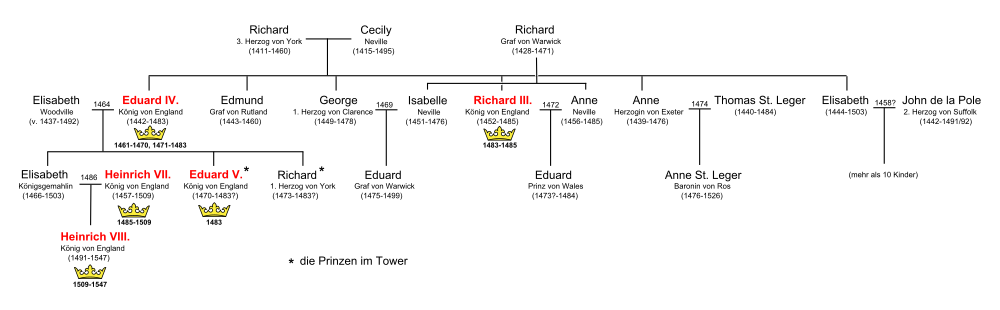

Richard was born at Fotheringhay Castle as the youngest of eight sons (four of whom survived) of Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York , and his wife Cecily Neville . As a member of the Plantagenet dynasty, which had ruled for 300 years, his father had weighty claims to the English throne, which at that time was King Henry VI. from the House of Lancaster, another line of the House of Plantagenet.

Richard's father and older brother Edmund, Earl of Rutland , died at the Battle of Wakefield during the Wars of the Roses when Richard was a boy. Richard was placed under the care of Richard Neville , the Earl of Warwick . Warwick is known in English historiography as a "kingmaker" because he exerted considerable influence on the progress of the Wars of the Roses. In 1461 he helped Heinrich VI. overthrow and replace him with Richard's eldest brother Edward IV .

Ascent in the shadow of Edward IV.

During Edward's reign, Richard proved his loyalty as the Duke of Gloucester . Especially in the late phase of the Wars of the Roses, he showed great abilities as a military leader. When Henry VI. briefly came back to the throne, Richard fled in October 1470 together with Eduard into exile in Bruges in Flanders . The middle brother of the two, George Plantagenet, 1st Duke of Clarence , allied with Warwick, who had meanwhile switched to the side of the Lancasters. On March 14, 1471 Richard returned to England in the entourage of Edward IV. On the march on London they met with George, who found Edward's forgiveness and rejoined the York house. Shortly thereafter, Edward finally struck the Lancaster house. The imprisoned and mentally unstable Heinrich VI. was murdered.

Immediately new arguments began, this time between the brothers George of Clarence and Richard of Gloucester. George, husband of Isabella Neville , daughter of the Earl of Warwick, was entitled to half of the extensive Neville estates that had been confiscated from the Crown. Since he had killed his brother-in-law Edward, the son of Henry VI., Who had been married to the younger Neville daughter Anne , he claimed the entire inheritance. Here, however, the then nineteen year old Richard, who wanted to marry Anne Neville, started. George could not completely ignore Richard's claims, but made his approval of the marriage in February 1472 dependent on the massive allocation of political offices and Neville lands by Edward IV. Richard was finally allowed to marry Anne, but was given relatively modest estates and the offices of Constable of England and Warden of the Forests North of the Tenth . Above all, the latter office enabled Richard to build a stable power base in the north of England in the years that followed. Above all, it achieved great popularity in the former Lancaster city of York . In addition, all sources indicate that his marriage to Anne was extremely harmonious. Richard and Anne had a son, Edward of Middleham (1473–1484), who died shortly after he was appointed heir to the throne . Anne also died before Richard.

Meanwhile, George sank ever further in the favor of his brother Edward IV. After the death of his wife Isabella in 1476 he tried to arrange a marriage with Maria , the heiress of Burgundy , which Edward forbade him. Shortly afterwards, when he put undue pressure on the courts in several trials, Eduard initiated a high treason case against his brother. On February 18, 1478, George's death was announced. According to a legend, he was drowned in a barrel of Malvasia wine after he was allowed to choose the way of death himself through a last act of grace by his brother.

Struggle for power

On April 9, 1483, Edward IV died surprisingly after a one-week illness. He left the kingdom to his eldest son, the twelve-year-old Edward V. He also appointed his brother Richard to be the guardian of Edward's nine-year-old brother Richard of Shrewsbury, 1st Duke of York . Together with the Privy Council , Richard was to rule the country during the minority of the heir to the throne.

The Privy Council, however, consisted of various contending parties, among them the Richards and the Queen widow Elizabeth Woodville . In April 1483 there were turbulent scenes when the factions of the throne council tried to win as many allies as possible in order to gain control over the underage heir to the throne, the state treasure and the fleet.

At the end of April Elizabeth Woodville was in possession of the treasury and the fleet, while Richard had won over the rich and militarily strong Lord Chancellor William Hastings, 1st Baron Hastings , and Henry Stafford , the Duke of Buckingham , both members of the Council of Thrones. Young Edward was with a strong bodyguard in Stony Stratford, near Nottingham . Richard met him there on April 30, 1483. He informed his nephew that his mother had obviously disregarded the last will of Edward IV and tried to prevent Richard's appointment as protector. Eduard then went into Richard's care, whether forced or voluntary. His court, including Earl Rivers , the commander of Edward's bodyguard and brother of the Queen, her second son Richard Gray and Edward's chamberlain Sir Thomas Vaughan were imprisoned. The Woodville faction in London reacted with panic. Elisabeth went with her children to Westminster Abbey , where they were granted asylum . Her brother left the country with the fleet. The rest of the Council of Thrones, on the other hand, approved Richard's move, who announced that he would be coming to London with his nephew for his coronation, where they moved in on May 4th.

Richard and the Duke of Buckingham became the dominant figures in the Privy Council. Parliament and a synod of the Church of England were convened to prepare for Edward's coronation. At Buckingham's instigation, the future king was to expect this time in the Tower of London , which at that time was a suitable place to live as a castle. Meanwhile, Lord Chancellor Hastings felt neglected by the rise of Buckingham. Together with other council members he took up contact with the Woodville faction, which was soon exposed: On June 13, 1483 Richard Hastings was accused of treason and immediately sentenced to death without trial. After confession, he was beheaded on a piece of lumber on Tower Green . Richard III used this. to take action against other members of the Woodville family. Earl Rivers, Richard Gray and Thomas Vaughan, who had been in Richard's captivity since April 30, were also executed. Jane Shore , a mistress of King Edward IV, his stepson Thomas Gray (who evaded prosecution by also seeking asylum in Westminster Abbey with his mother), and finally the new Lord Hastings, were penalized for minor offenses and publicly sentenced to brief imprisonment.

In the meantime, Robert Stillington , the Bishop of Bath and Wells , had begun to proclaim in London that the children of Elizabeth Woodville and Edward IV were illegitimate because the king, before marrying Elizabeth, had married Eleanor Butler , the Count's daughter, who had since died of Shrewsbury, got engaged. This allegation could not be proven, but it quickly spread in London. The logical conclusion was that Richard had to be considered the legitimate heir to the throne: the older Richard brothers were dead. The sons of George Plantagenet were out of the question, as they were unworthy of the throne by their father's plot. Whether Richard really believed Stillington's accusations, or whether he saw them simply as an opportunity to usurp the throne, can no longer be clarified today. On June 23, Buckingham represented Richard's claim to the throne at a meeting of nobility. On June 25, the English parliament declared Richard the rightful heir to the throne. It explained its actions a few months later in a document entitled Titulus Regius , of which only one copy has survived.

Richard as king

One day after the parliamentary decision, on June 26, 1483, Richard III. as the last king from the House of Plantagenet , to which the House of York belonged as a branch line, to his rule. The coronation took place on July 6th. The princes Eduard and Richard stayed in the tower ( see: Princes in the Tower ).

On September 8, Richard III. Son Edward of Middleham invested in York as the Prince of Wales . He thus carried the traditional title of the English heir to the throne. Sir James Tyrell, one of Richard's henchmen, was commissioned these days to bring regalia from the Tower of London and festive attire for the royal squires to York for the occasion. This errand is repeatedly associated with the disappearance of young Eduard and his brother Richard. Perhaps Richard III. Tyrell hires to murder his nephews. However, the (shortly afterwards treacherous) Duke of Buckingham - who was a connoisseur of England and as such had access to the Tower at all times - was in London at the time of the presumed death of the children. The children were also an obstacle to the throne for Heinrich Tudor, who would later become Henry VII , who was supported by the duke . Ultimately, however, their fate could never be finally determined. They disappeared in the late summer of 1483. They were presumably murdered, but even that is not clearly proven, despite later finds of children's skeletons in the Tower.

Richard III immediately after he came to power, began removing Woodville officials from important positions in the kingdom. In October 1483 he had his former ally Henry Stafford, the 2nd Duke of Buckingham, proclaimed a traitor. Buckingham had contacted Henry of the Welsh House of Tudor and encouraged him to invade England. Heinrich was a descendant of the widow of Henry V and, through his mother, a descendant of John of Gaunt and thus the last heir to the House of Lancaster. On November 2nd, the Duke of Buckingham was executed. In early April 1484, the heir to the throne Edward , Queen Anne, died on March 16, 1485. There are rumors that Richard then tried to get married to his niece Elizabeth of York , daughter of Edward IV , at the church . In fact, negotiations about a marriage between Richard and Joan of Portugal and, at the same time, Elizabeth with the Portuguese heir to the throne, Manuel, took place at this time.

Defeat and death

On August 7, 1485, Heinrich Tudor finally landed in England. In Milford Haven , he went ashore with Welsh and French troops and a mercenary contingent. Without encountering significant resistance, he was able to reach Lichfield in an urgent march . Richard went to meet him, and on August 22nd at Market Bosworth there was a contest for the crown of England.

At first, Richard III. to keep the upper hand with his numerically superior army; However, when he tried to attack the passively acting Heinrich Tudor directly, Richard's ally Sir William Stanley , a brother of Heinrich's stepfather, switched sides. For Richard this meant the death sentence. It is said that he was slain with a battle ax by the Welsh nobleman Rhys ap Thomas .

Burial and succession

Richard's body was desecrated, exhibited naked in The New Wake tavern in Leicester , also to prove to his followers that the Yorkists' cause was lost, and finally buried in Greyfriars Church in the Franciscan monastery there.

With Richard's successor, Henry VII, the era of the Tudor kingdom began . Heinrich Tudor had all doubts about his claim to the title of king removed by parliament in November 1485. This quickly established that he was the rightful King of England, since he actually held the throne. In addition, the beginning of Henry's reign was dated back to the eve of Bosworth, so that Richard III. and could declare 28 of his main supporters high traitors.

In 1495 Henry VII provided 50 pounds (equivalent to 40,000 pounds today) for a marble sarcophagus and an alabaster monument. However, knowledge of the exact location of the burial site was lost in the following centuries. It was alleged that Richard's body was thrown into the nearby River Soar during the dissolution of the English monasteries .

Marriage and offspring

Richard III married Lady Anne Neville , daughter of Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick , and widow of Edward of Lancaster , around 1472 . Only the son Edward of Middleham (* around 1474/76; † 1484) emerged from the marriage.

Richard also recognized two illegitimate children:

- John of Gloucester (also John of Pontefract ); he was made Captain of Calais in March 1485 and received an annual salary of £ 20 under Henry VII from the Kingston Lacy estate in Dorset , which had belonged to his father. His later career is unknown. The illegitimate son of Richard, who died in the Tower at the time of the Warbeck-Warwick conspiracy, is believed to have been this John.

- Katherine; she was betrothed to William Herbert, Earl of Huntingdon , in February 1484 . The marriage should be concluded before November 29th. At the coronation of Elizabeth of York on November 25, 1487, however, Herbert is called a widower. As a result, either Katherine had died or Herbert had broken the promise of marriage.

Afterlife

Reception in the Tudor period

William Shakespeare wrote the tragedy of King Richard III around 1593 . She portrays the king as an unscrupulous power man who is driven from one crime to the next in order to gain power and to secure it. Shakespeare lets Richard III. appear in the first scene of the first act with the following words (translation by August Wilhelm Schlegel ):

- I, shortened by this beautiful proportion,

wrongly cheated out of education by nature,

distorted, neglected, sent ahead of time

into this world of breathing, half barely finished

, and so lame and unseemly

that dogs bark, I limp wherever over -

[…]

And because I cannot, as a lover,

shorten these eloquently eloquent days,

Am I willing to become a villain

And hostile to the vain joys of these days.

In this image of Richard as the villain on the English throne little has changed in the general consciousness up to the present day. The rulers of the House of Tudor, including Elizabeth I , during whose time Shakespeare wrote his drama, were very interested in making the opponent of the founder of their dynasty appear in an unfavorable light.

Later literary adaptations of his character contributed to the bad press for Richard. As in Shakespeare, he is often portrayed as a cripple, which at the time was considered evidence of a malicious character. A well-known image showing him with his humpback was in all probability manipulated as early as the Tudor period. The few contemporary descriptions describe him rather as a slight, albeit very wiry and battle-hardened man. The latest scientific research using 3D printing has shown that he did not suffer from a hump , but from scoliosis . A fight on the battlefield would probably not have been possible with such physical impairments, especially because of the heavy armor and weapons.

The historical material about Richard III. was processed into dramas again and again after Shakespeare, for example by Hans Henny Jahnn , who wrote the play The Coronation of Richard III in 1921 .

Today's reception

Today's historians view the dubious reputation that Richard has enjoyed since his death primarily as a result of the unclear historical tradition in the Tudor era. More recently, it turned out that he could not have committed most of the crimes reported to him. It is not yet clear whether he was actually responsible for the deaths of his two nephews, the princes in the Tower .

In 2002 by the British television channel BBC broadcast program 100 Greatest Britons Richard III was. voted 82nd on the list in a non-representative telephone vote. Approximately 450,000 UK citizens took part in the vote.

On February 5, 2013, scientists in London presented a three-dimensional head model of Richard III. made under the direction of Caroline Wilkinson, Professor of Craniofacial Identification at the University of Dundee in Scotland, using the skull found in 2012. The Richard III Society, which financed the reconstruction, hopes that this will change the Shakespearean image of Richard III. as an unscrupulous ruler.

In 2016, Shakespear's play was newly filmed by the BBC as a conclusion to their series The hollow crown .

Rediscovery and examination of the bones

excavation

On August 25, 2012, excavation work began in a parking lot in the central English city of Leicester . Researchers from the University of Leicester and the Richard III Society suspected Richard's grave on the site, the only undeveloped part of a former Franciscan monastery. The parking lot was exactly where the "Greyfriars church" used to be.

At the beginning of September 2012, a human skeleton was found during the excavations. The unambiguous identification of the bones as the Richards III. was announced at a press conference at the University of Leicester on February 4, 2013.

Anatomical findings and isotope research

The skeleton is that of a man of medium stature, about 30 years old, who died between 1455 and 1540 according to radiocarbon dating . The bones show a total of ten injuries, eight of them on the head, all of which were caused near the time of death. According to another evaluation, there are a total of eleven injuries, nine of them on the head. The cause of death was probably two severe blows to the skull, which were probably caused by a halberd and a sword . Other bone damage was probably caused later, including a serious injury to the hip, as it was actually protected by the armor that was common at the time. The scientists assume that Richard III. had taken off his helmet in the battle of Bosworth Field or lost it in battle. He might have got off the horse because it got stuck in the mud.

The bones also show a pronounced misalignment of the spine ( scoliosis ), which probably developed from the age of ten. This misalignment is considered by several biographers as a physical characteristic of Richard III. handed down.

Using isotope analysis of a tooth, a thigh bone and a rib, it was also possible to prove that Richard lived in Wales as a child and that in the last years of his life he consumed a lot of wild birds and wine, as served at royal banquets.

DNA examinations

The assumption that the remains found are the bones of Richard III. was confirmed after DNA analysis in February 2013. The mitochondrial DNA found in the bones was compared with that of a direct descendant of Richard's sister Anne of York in the 17th generation, the London-based Canadian Michael Ibsen. This is related to Richard through his mother Cecily Neville in a purely maternal line. To confirm the result, the mitochondrial DNA of another - previously anonymous - descendant of Cecily Neville was compared in the maternal line, which also matched. It took historian John Ashton-Hill three years to track down the descendants who were unaware of their royal ancestry. With them, the line dies out, so that a DNA comparison at a later point in time would probably have been impracticable.

When comparing the Y-chromosomal DNA Richards III. with five anonymous living male descendants of Henry Somerset, 5th Duke of Beaufort , from the last flowering bastard line of the Plantagenets, four of the subjects showed a match, but none with the Y-chromosome type of the skeleton. Perhaps it happened in the 19th generation between Richard III. and Henry Somerset on false paternity. Whether in the York or Beaufort houses could not be determined exactly.

Reburial

On March 22, 2015, the bones of Richard III. transferred to Leicester in a plain oak coffin with military honors. The coffin was on display for three days and viewed by 20,000 visitors, who placed thousands of white roses (the symbol of the House of York) there. Richard's bones were reburied in a lead coffin in Leicester Cathedral on March 26, 2015 after a week-long celebrations in several Leicestershire locations linked to his life story . The Richard III Society had donated 10,000 pounds for a corresponding tomb . Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby presided over the funeral service.

The choice of burial site had caused controversy; it has been criticized that Richard III. was not buried in York.

literature

Specialist literature

- John Ashton-Hill: Last Days of Richard III and the Fate of His DNA. History Press, Stroud 2013, ISBN 9780752492056

- Michael Hicks: Richard III. Tempus Publishing Limited, Stroud 2000, ISBN 0-7524-2589-7 .

- Paul M. Kendall: Richard III. Callwey, Munich 1980, ISBN 3-7667-0520-2 .

- AJ Pollard: Richard III and the Princes in the Tower. Bramley Books, Godalming 1997, ISBN 1-85833-772-0 .

- Charles Ross: Richard III. Methuen, London 1981 (several NDe).

Fiction representations

- Sharon Kay Penman: The Sunne in Splendor. Ballantine Books, New York 1982, ISBN 0-345-36313-2 .

- Rosemary Hawley-Jarman: The York Sun. (Translated from the English by Manfred Vogel) Molden, Munich 1972, ISBN 3-217-00427-2 .

- Charlotte Kaufmann: The Rose of York. Richard III and Ann Neville. Munich 1989.

- Anne Easter Smith: The Rose of England. (historical Roman. Orig. A Rose for a Crown . German 2006)

- Josephine Tey : Alibi for a King. (German 1959 under the title: Richard the Verleumdete), ISBN 3-7254-0184-5 .

- Elizabeth George : I, Richard. Bantam Books, New York 2002, ISBN 0-553-80258-5 .

Web links

- Literature about Richard III. in the catalog of the German National Library

- Andreas Kalckhoff, Richard III. - Brief information: [2] , [3]

- Andreas Kalckhoff, Richard III. - Reviews

- Exact description of the state of research regarding the whereabouts of Richard's remains

- Richard III Society (English)

- The Richard III Foundation, Inc. (English)

- University of Leicester : The Greyfriars Project - full page on the university's excavations

- University of Leicester: University website on the skeleton find and examinations

- University of Leicester: University website for the press conference on February 4, 2013

- Nine blows to the head: King Richard III. died in agony , Der Spiegel Online from September 17, 2014.

Individual evidence

- ↑ According to the statement of the chief archaeologist Richard Buckley: "... convinced beyond reasonable doubt ..."

- ^ J RA Griffiths: Rhys, Sir, ap Thomas (1448 / 9-1525). In: Henry Colin Gray Matthew, Brian Harrison (Eds.): Oxford Dictionary of National Biography , from the earliest times to the year 2000 (ODNB). Oxford University Press, Oxford 2004, ISBN 0-19-861411-X , ( oxforddnb.com license required ), as of 2004

- ^ Llandeilo through the ages: Sir Rhys ap Thomas. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on July 4, 2008 ; Retrieved August 21, 2013 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Photo gallery - image 6 - Find in Leicester: lead coffin discovered next to royal tomb. In: Spiegel Online photo gallery. July 29, 2013, accessed June 9, 2018 .

- ↑ David Baldwin: King Richard's Grave in Leicester . Transactions (Leicester: Leicester Archaeological and Historical Society) 60: 21-22. 1986 ( online version (PDF; 560 kB) ).

- ^ Excavation in Leicester: Archaeologists discover mysterious casket in the casket; Richard III .: ( [1] ) Spiegel Online, July 29, 2013.

- ↑ Rosemary Horrox: Richard III. (1452-1485). In: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004.

- ^ Shakespeare Richard III, I1, in the translation by Schlegel (projekt-gutenberg.org), accessed on February 5, 2013.

- ↑ Text ( Memento of the original dated August 31, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ↑ geschichte-wissen.de: Richard III. - King of England

- ↑ The 100 Greatest Britons. Retrieved August 27, 2012 .

- ↑ Richard III. with a new face. FAZ , February 5, 2013, accessed on February 5, 2013 .

- ↑ imdb.com: Richard III

- ^ Richard Buckley1, Mathew Morris, Jo Appleby, Turi King, Deirdre O'Sullivan and Lin Foxhall : 'The king in the car park': new light on the death and burial of Richard III in the Gray Friars church, Leicester, in 1485 . (PDF; 5.6 MB) Antiquity Journal Volume: 87 Number: 336 Page: 519–538, June 2013, accessed on May 24, 2013 (English).

- ↑ Grave of Richard III may be under parking lot - Discovery News, August 24, 2012

- ^ The Queen asks: Was Richard III REALLY found buried under a car park? Article dated February 27, 2014 on mirror.co.uk

- ↑ Thomas Kielinger: Humiliation rituals, statuted on a naked corpse. Die Welt , February 4, 2013, accessed February 5, 2013 .

- ^ Search for Richard III: momentous day as University announces discovery. University of Leicester, February 4, 2013, accessed December 3, 2014 (video of the press conference).

- ↑ Richard III dig: DNA confirms bones are king's. BBC News, February 4, 2013, accessed February 4, 2013 .

- ↑ Richard III. died when he lost his helmet welt.de, September 17, 2014.

- ↑ Angelika Franz: Bones reveal the king's favorite food, Spiegel Online, August 19, 2014.

- ↑ Angela L. Lamb et al .: Multi-isotope analysis demonstrates significant lifestyle changes in King Richard III Journal of Archaeological Science, Vol. 50, October 2014, pp. 559-565.

- ^ Bones under the parking lot belong to King Richard III , Spiegel Online, February 4, 2013 (accessed February 6, 2013).

- ^ University of Leicester: Maternal Relationship between Richard III. and Michael Ibsen .

- ↑ a b University of Leicester: Genealogy of the descendants of Cecily Neville .

- ↑ Richard III dig: How search reached Leicester car park. BBC News, September 7, 2012, accessed February 6, 2013 .

- ↑ see Dr. John Ashton-Hill: Last Days of Richard III and the Fate of His DNA. History Press, 2013.

- ↑ And the kingdom? The horse? Who is digging them up? FAZ , February 4, 2013, accessed on February 6, 2013 .

- ^ Richard III - DNA results - University of Leicester. Retrieved February 17, 2020 .

- ^ Paul Rincon: Richard III's DNA throws up infidelity surprise. BBC News, December 3, 2014, accessed December 3, 2014 .

- ↑ Richard III: Leicester welcomes king's remains. BBC News, March 22, 2015, accessed March 22, 2015 .

- ^ Richard III: 20,000 visit coffin in Leicester Cathedral. BBC News, March 25, 2015, accessed March 26, 2015 .

- ↑ http://leicestercathedral.org/king-richard-iii-reinterred-march-2015-2/

- ↑ http://www.express.co.uk/news/history/496639/King-Richard-III-will-get-a-state-funeral-at-Leicester-Cathedral-next-month

- ↑ http://kingrichardinleicester.com/

- ^ Guardian.co.uk , accessed January 24, 2015.

- ↑ Richard III. solemnly buried , Deutsche Welle, March 26, 2015

- ↑ Richard III: Leicester Cathedral reburial service for king. March 26, 2015, accessed March 26, 2015 .

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Edward V. |

King of England Lord of Ireland 1483–1485 |

Henry VII |

| New title created |

Duke of Gloucester 1461-1483 |

Title merged with the crown |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Richard III |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | King of England (1483–1485) |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 2, 1452 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Fotheringhay Castle , Northamptonshire , England |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 22, 1485 |

| Place of death | at Market Bosworth , Leicestershire , England |