Salar de Atacama

| Salar de Atacama | ||

|---|---|---|

|

||

| In the light of the setting sun, the glistening white that can be seen during the day changes into a splendid play of colors. | ||

| Geographical location | Atacama Desert , Antofagasta Region , Chile | |

| Tributaries | Río San Pedro (14 l / s), Río Aguas Blancas (4.4 l / s), Río Villama (4 l / s), Río Tilomonte (2.4 l / s), Río Honar (0.6 l / s) s), mountain streams of Jerez, Talabre, Camar, Peine, Tarajne and Tulán, precipitation rates : <3 - 50 mm / a |

|

| Drain | none, evaporation rates 1800 - 3200 mm / a |

|

| Places on the shore | San Pedro de Atacama | |

| Data | ||

| Coordinates | 23 ° 24 ′ S , 68 ° 15 ′ W | |

|

|

||

| Altitude above sea level | 2300 m | |

| surface | 3,051 km 2 of which 12.6 km 2 water level |

|

| length | 90 km | |

| width | 35 km | |

| Maximum depth | 1700 m | |

| Middle deep | 650 m | |

| Catchment area | 15,620 km² | |

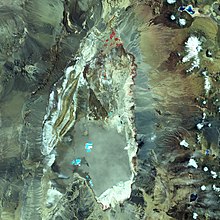

The Salar de Atacama ( Spanish salt point of Atacama) is the largest active evaporite basin in the Antofagasta district in northern Chile . The salar is located in the Atacama Desert , in a depression without drainage at the foot of the Andes Cordillera , surrounded by numerous populated oases. It consists of a hard, rough, white layer of salt contaminated with desert sand. Underneath is a brine containing lithium . Incoming water emerges in sporadic pools that form important biotopes .

geography

location

The Salar de Atacama belongs to the municipality of San Pedro de Atacama in the east of the Región de Antofagasta near the border with Bolivia . The region is part of the Atacama Desert , one of the driest and most lonely landscapes on earth. The salar lies in the depression of a 15,620 km 2 drainless water catchment area. The depression is a tectonic rift . In the west the salar is bounded by the Cordillera Domeyko , in the east by the Andes cordillera , in the south by the Cordón de Lila and in the north by the sediment deposits of the deltas of the Río San Pedro and Río Villama .

In the wider area of the salar there are thermal springs , geysers and volcanoes . The most famous volcano is the Licancabur with 5920 m height.

description

With an extension of 3,051 km 2 , it is the largest salar in Chile. It consists of two units, a core and an edge zone. The core has a surface area of 1100 km 2 , reaches a depth of 1.7 km and consists of 90% solid, porous sodium chloride permeated by brine . The brine has a very high density of 1.238 kg / l and is rich in lithium , potassium , magnesium and boron . The edge zone lies around the core. It consists of fine salty (mainly gypsum ), loamy sediments.

Where the few water tributaries reach the salar, there are a number of oases that have been inhabited since prehistoric times. The precipitation rates in the Salar are extremely low. The annual rates for rain vary from less than 3 mm / a to a maximum of 50 mm / a. The evaporation rates in the salar also reach extreme values, they vary from 1800 mm / a to 3200 mm / a.

Emergence

The salar consists of clastic sediments and evaporites left by a dry paleo lake. Due to climatic fluctuations, a lake has appeared at this point four times in the past hundred thousand years. The oldest lake was there 75,700 to 60,700 years ago, the last 6,200 to 3,500 years ago.

According to an estimate from 1996, the salar reaches 52 million cubic meters of water annually through above-ground and 90 million cubic meters through underground tributaries. Of this, 27 million cubic meters will be diverted for agricultural irrigation. In addition, there is an average of 30 million cubic meters of precipitation over the salar. Dissolved in the water, 335,000 tons of salts are brought into the salar every year, including 270 tons of lithium and 5,300 tons of potassium. Every year, 145 million cubic meters of water evaporate in the salar. The core of the salar receives 0.1 mm of new salt sediments per year.

Wetlands in the Salar

The main water tributaries from the north bring two rivers. The Río San Pedro forms a dry delta. The Río Villama seeps south of San Pedro and provides underground contributions for the water bodies that occur sporadically there. From the Andes to the east there are contributions from groundwater and the mountain streams of Jerez, Talabre, Camar, Peine, Tarajne and Tulán. Where the water comes to the surface, small ponds and shallow lakes are created that contain high concentrations of salt that few higher organisms can tolerate. These include saltwater crabs , some copepods, and some macrophytes . The water level of these lakes is 12.6 km 2 in total .

Artemia franciscana lives in the pools of the Salar.

The following wetlands are distinguished:

( Map with all coordinates: OSM | WikiMap )

![]()

- Northern salar:

- Laguna Baltinache ( 23 ° 2 ′ S , 68 ° 14 ′ W )

- Laguna Cejas ( 23 ° 3 ′ S , 68 ° 13 ′ W ) (bathing lake: surface 3 ha, average water depth 10 m)

- Laguna Piedra ( 23 ° 4 ′ S , 68 ° 13 ′ W ) (swimming lake)

- Laguna Tebinquiche ( 23 ° 8 ′ S , 68 ° 15 ′ W ) (One of the two largest salt lakes in the Salar)

- Ojos de Tebinquiche ( 23 ° 8 ′ S , 68 ° 14 ′ W )

- Laguna Llona

- Lagunas Gemela Este and Gemela Oeste (In the Tebenquiche plain, surface <1 km 2 , maximum depth 7 m, distance between the two 100 m)

- Eastern salar:

- Sector Soncor (61 km south of San Pedro. Area of the protected area 50.16 km 2. Three permanent lakes and a canal)

- Laguna Puilar ( 23 ° 18 ′ S , 68 ° 9 ′ W )

- Laguna Chaxa ( 23 ° 17 ′ S , 68 ° 11 ′ W ) (surface 13 km 2 , most important body of water in the salar. Salinity (TDS value) 86 g / l, pH 7.6)

- Estación Chaxa, Puente San Luis ( 23 ° 20 ′ S , 68 ° 10 ′ W ) (visitor area of the Laguna Chaxa)

- Laguna Barros Negros ( 23 ° 21 ′ S , 68 ° 9 ′ W )

- Canal or Río Burro Muerto (Comes from the river delta, connects Laguna Puilar and Laguna Chaxa and flows into Laguna Barros Negros)

- Sector Aguas de Quelana (72 km south of San Pedro. Area of the reserve 41.35 km 2 )

- Laguna Burro Muerto ( 23 ° 28 ′ S , 68 ° 6 ′ W ) (accumulation of small ponds of shallow depth, characterized by seasonal flooding)

- Sector Soncor (61 km south of San Pedro. Area of the protected area 50.16 km 2. Three permanent lakes and a canal)

- South Salar:

- Sector Aguas de Peine (three permanent lakes)

- Laguna Salada ( 23 ° 41 ′ S , 68 ° 8 ′ W )

- Laguna Saladita ( 23 ° 41 ′ S , 68 ° 9 ′ W )

- Laguna Interna ( 23 ° 40 ′ S , 68 ° 9 ′ W )

- Laguna (no name) ( 23 ° 40 ′ S , 68 ° 9 ′ W )

- Sector Aguas de Tilopozo

- Laguna La Punta ( 23 ° 43 ′ S , 68 ° 14 ′ W )

- Laguna Brava ( 23 ° 44 ′ S , 68 ° 15 ′ W )

- Sector Aguas de Peine (three permanent lakes)

economy

The Salar de Atacama is used for non-metal mining and tourism.

Mining

The salar houses about 27% of the world's lithium reserves, as well as borax and potassium salts . For extraction , water with the dissolved salts is pumped up and fed into shallow basins, where it evaporates. Potassium chloride and potassium sulfate precipitate, while lithium and boron remain dissolved in the supernatant. This brine is pumped through pipes for further processing.

Due to the high water consumption for the extraction of metals and salts, the water level in the central lagoon has already sunk, which will lead to a long-term problem for the flamingos nesting there. Already now (May 2019) more and more carob trees are drying up , actually robust desert plants that dig their roots deep.

Since 1996, lithium chloride solution has been obtained from the Salar de Atacama as a by-product of potassium chloride extraction. There are currently three large plants in the Salar that produce potassium chloride, potassium sulfate, boric acid and lithium brine. The lithium chloride is brought to a plant in Salar del Carmen near Antofagasta, where it is processed into lithium carbonate and lithium hydroxide. In 2012, SQM Salar SA produced 45,700 tons of lithium (calculated as lithium carbonate) valued at USD 222.2 million. That corresponded to 35% of the lithium traded worldwide in the same year. The rights to the exploitation of raw materials are regularly the subject of violent legal and political disputes.

tourism

The Salar de Atacama is one of the main attractions in the region. 70,000 tourists come to the Salar every year.

A small part of the east of the Salar belongs to the Los Flamencos National Reserve . The reserve owes its name to the large populations of flamingos . In addition to the flamingos, many other birds live in these wetlands of the Salar. B. Darwin's rheas , geese and ducks . In the areas bordering the Salar to the east, llamas , guanacos , vicuñas and alpacas can also be found in large numbers.

Web link

supporting documents

- ^ A b c Francois Risacher, Hugo Alonso, Carlos Salazar: Geoquimica de aguas en cuencas cerradas: I, II, y III Regiones - Chile . Estudio de cuencas de la II Región. Vol III. Santiago de Chile January 1999, Salar de Atacama, p. 57–75 (Spanish, 295 p., Uantof.cl ( Memento from March 5, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) [PDF; 960 kB ]).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h CADE-IDEPE Consultores en Ingenería: Cuenca de Salar de Atacama . In: Gobierno de Chile Ministerio de Obras Públicas Direccón General de Aguas (ed.): Diagnostico y clasificación de los cursos y cuerpos de agua según objetivos de calidad . Santiago de Chile December 2005 (Spanish, sinia.cl [PDF; 887 kB ; accessed on April 21, 2013]). sinia.cl ( Memento of the original from April 17, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b c d e f Vera Thiel, Marcus Tank, Sven C. Neulinger, Linda Gehrmann, Cristina Dorador, Johannes F. Imhoff: Unique communities of anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria in saline lakes of Salar de Atacama (Chile): evidence for a new phylogenetic lineage of phototrophic Gammaproteobacteria from pufLM gene analyzes . In: FEMS Microbiology Ecology . tape 74 , no. 3 , December 2010, p. 510-522 , doi : 10.1111 / j.1574-6941.2010.00966.x ( onlinelibrary.wiley.com [accessed June 7, 2013]).

- ↑ a b c d Salar de Atacama, Chile . Sheet SF 19-15. In: US National Imagery and Mapping Agency (Ed.): Series 1501 (= Latin America, Joint Operations Graphic 1: 250,000 [Not for navigational use] ). Defense Mapping Agency Topographic Center ( lib.utexas.edu [accessed March 14, 2013]).

- ↑ a b c Claudia González Muzzio: Actualización Plan Regulador Comunal de San Pedro de Atacama . Memoria explicativa. Ed .: Ilustre Municipalidad de San Pedro de Atacama. March 2010 (Spanish, e-seia.cl [PDF; 2.4 MB ; accessed on March 13, 2013]).

- ↑ a b c SQM Salar SA (ed.): Declaración de impacto ambientalproyecto “Ampliación Planta SOP” . Anexo I. Characterization of the area of influence. 2010 ( e-seia.cl [PDF; 5.7 MB ; accessed on June 10, 2013]).

- ↑ Cf. Diccionario de la lengua española , Real Academía Española

- ↑ a b T. Boschetti, G. Cortecci, M. Barbieri, Margherita Mussi : New and past geochemical data on fresh to brine waters of the Salar de Atacama and Andean Altiplano, northern Chile . In: Geofluids . tape 7 , 2007, p. 33–50 , doi : 10.1111 / j.1468-8123.2006.00159.x ( researchgate.net [PDF; 2.1 MB ; accessed on June 9, 2013]).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h J. Salas, J. Guimerà, O. Cornellà, R. Aravena, E. Guzmán, C. Tore, W. von Igel, R. Moreno: Hidrogeología del sistema lagunar del margen este del Salar de Atacama (Chile) . In: Boletín Geológico y Minero . tape 121 , no. 4 , 2010, ISSN 0366-0176 , p. 357–372 ( igme.es [PDF; 703 kB ; accessed on June 9, 2013]).

- ^ A b Hugo Alonso, Francois Risacher: Geoquimica del Salar de Atacama . Part 1: origen de los componentes y balance salino. In: Revista Geológica de Chile . tape 23 , no. 2 , December 1996, p. 113–122 ( andeangeology.equipu.cl [accessed June 7, 2013]).

- ^ Lautaro Núñez, Martin Grosjean, Isabel Cartajena: Human Occupations and Climate Change in the Puna de Atacama, Chile . In: Science . tape 298 , 2002, ISSN 1095-9203 , pp. 821–824 ( [1] [PDF; accessed June 4, 2013]).

- ^ Andrew L Bobst, Tim K Lowenstein, Teresa E Jordan, Linda V Godfrey, Teh-Lung Ku, Shangde Luo: A 106 ka paleoclimate record from drill core of the Salar de Atacama, northern Chile . In: Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology . tape 173 , no. 1–2 , September 1, 2001, pp. 21–42 , doi : 10.1016 / j.bbr.2011.03.031 ( sciencedirect.com [accessed June 9, 2013]).

- ↑ a b Gonzalo M. Gajardo, John A. Beardmore: Electrophoretic evidence Suggests did the brine shrimp found in the Salar de Atacama, Chile, is A. franciscana Kellogg . In: Hydrobiologia . tape 2 , no. 257 , April 1993, p. 65-71 ( link.springer.com [accessed June 10, 2013]).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p coordinates determined with GoogleEarth, June 2013

- ↑ Cecilia Demergasso, Lorena Escudero, Emilio O. Casamayor, Guillermo Chong, Vanessa Balagué, Carlos Pedrós-Alío: Novelty and spatio-temporal heterogeneity in the bacterial diversity of hypersaline Lake Tebenquiche (Salar de Atacama) . In: Extremophiles . tape 12 . Springer, March 18, 2008, p. 491–504 , doi : 10.1007 / s00792-008-0153-y ( zjubiolab.zju.edu.cn [PDF; 516 kB ; accessed on June 7, 2013]).

- ^ Carlos Guerra Correa, Alejandra Malinarich Rodriguez: Bioversidad de la zona de desierto y tropical de altura en la II Región de Antofagasta . 2004 ( de.scribd.com [accessed June 7, 2013]).

- ↑ De los Ríos-Escalante: Morphological variations in Boeckella poopoensis (Marsh, 1906) (Copepoda, Calanoida) in two shallow saline ponds (Chile) and potential relation to salinity gradient . In: International Journal of Aquatic Science . tape 2 , no. 1 , 2011, ISSN 2008-8019 , p. 80-87 ( aquaticscience.e-journalsdirect.com [PDF; 556 kB ; accessed on June 10, 2013]). aquaticscience.e-journalsdirect.com ( Memento of the original from July 11, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b c d Hernán Torres Santibáñez, Marcela Torres Cerda: Los Parques Nacionales de Chile . A guide to the visit. Editorial Universitaria, 2004, ISBN 956-11-1701-0 , p. 161 ( books.google.de [accessed June 10, 2013]).

- ↑ a b c d e f Gestión Ambiental Consultores: EIA Modificaciones y Mejoramiento del Sistema de Pozas de Evaporación Solar en el Salar de Atacama . Anexo 8 Comportamiento Histórico Variables Asociadas Sistema Lagunar Peine y La Punta y La Brava. Ed .: Sociedad Chilena de Litio Ltda. 2009 ( e-seia.cl [PDF; 2.7 MB ; accessed on June 7, 2013]).

- ^ The Saudi Arabia of Lithium.

- ↑ zdf.de of September 9, 2018, E-Autos: An apparently clean business, especially the section "Problem Lithium", accessed on May 4, 2019.

- ↑ tagesspiegel.de of May 21, 2019, overexploitation for e-cars? , (in particular section The environment suffers too ), accessed on May 28, 2019.

- ^ Sociedad Química y Minera de Chile SA (ed.): DOS MIL DOCE SQM MEMORIA ANUAL . Santiago de Chile 2013 (Spanish, ir.sqm.com [PDF; accessed July 14, 2013]).

- ↑ cambio21.cl ( Memento of the original from August 12, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Ficha Informativa CONAF (PDF; 249 kB)