Valley festival

| Valley festival in hieroglyphics | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Middle realm |

Heb-en-inet-neb-hapet-Re Ḥb-n-jnt-nb-ḥ3pt-Rˁ Festival of the Valley of Mentuhotep II. (Neb-hapet-Re) |

|||||||||

| New kingdom |

Heb-en-inet Ḥb-n-jnt festival of the valley |

|||||||||

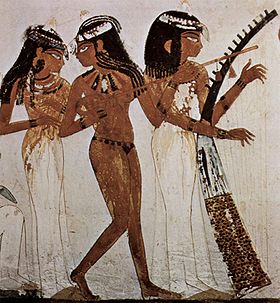

| Musicians at the festival ( grave of the night ) | ||||||||||

The valley festival (also “ Beautiful festival of the desert valley ”, “ rowing trip of the west ”) was one of the Theban sky festivals in ancient Egypt and fell annually in the ancient Egyptian season of Schemu . During the first ascent under Mentuhotep II , the valley festival was celebrated in September during the Nile flood , which was drawing to a close . As a necropolis festival , it was directly related to the cult of the dead . In the New Kingdom , the valley festival, alluding to the goddesses Hathor , Sachmet and Bastet, was also understood as the “ festival of drunkenness ”, as the “Soothing of Sekhmet” festival took place in Esna at the same time. The Theban population did not take directly at the procession and the boat crossing of Amun in part, but committed suicide in equating the "Day of noise Trunks " as " hard in the grave "

Processes of the valley festival, as they were celebrated by the population, are documented for the first time at the beginning of the 18th dynasty . Images of the sacrificial rituals and the procession, on the other hand, only appear in the temples of the kings, since those ordinances were not accessible to the "simple Egyptian". The pictorial program of the royal temples and the tombs complemented each other and thus included the entire framework of the valley festival. The tomb paintings therefore concentrated on the one hand on the holy Amun barque, which stopped at the mortuary temples of the deceased kings on arrival in Thebes , and finally on the sanctuary of the reigning ruler, and on the other hand on the ceremonial rites of the grave owner.

At the time of Hatshepsut, the festival “ Train to Chemmis ” was integrated into the processions to celebrate the annual rebirth of the king as Horus . In this respect, the valley festival consisted of several small festivals that gradually supplemented the festival calendar.

History of the valley festival

The occasion and content of the Talfest celebrations changed considerably in the course of Egyptian history. In the early 18th dynasty, old traditions were in the foreground, such as dedications during ritual sacrifices , transfigurations at the feast and visits to the temple guards and harem ladies of the goddess Hathor. In the further course of the event, different sections of the population were given the opportunity to travel to the land of the dead . The former union of Amun and Hathor, which had the character of a rebirth festival, combined with the innovations without changing old rites. Only the sequence of the framework activities was changed from the middle of the 18th dynasty at the latest and adapted to the new needs.

Only after large parts of the population were able to take part in the festivities did the valley festival turn into a jubilee celebration, to which the priesthood welcomed visitors to the graves with flowers. The homage to the deity Amun-Re and the accompanying ceremonies of the dance were supplemented by intoxicating drinking bouts. After the Amarna period , the “old spirit of the valley festival” revived in the 19th dynasty . The cultural decline of the 20th Dynasty replaced joyful activities with sad rites . Pictorial representations of the earlier carelessness were reduced from this point on in order to later disappear completely.

origin

The valley festival is still unknown in the festival lists of the Old Kingdom . After the fall of the Egyptian Empire at the end of the Old Kingdom, the kings of the ninth and tenth dynasties chose Herakleopolis Magna as their residence , which was later conquered by Mentuhotep II . The Amun Temple in Karnak was first mentioned in history during this period . Under Mentuhotep II, the unification of the empire could only be accomplished by taking into account the King and Horus ideology of the Old Kingdom, which is also visible in the structural elements used in the mortuary temple of Mentuhotep II since the unification of the empire.

The valley of Mentuhotep II was under the sign of Hathor , who was venerated as the sky goddess and mother of Horus in a chapel above the mortuary temple in her manifestations as a holy cow and as the mistress of the papyrus thicket . The valley festival is mentioned for the first time on a rock graffito for Neb-hepet-Re (Mentuhotep II), which was attached by a priest above his mortuary temple:

"( First month of the season Schemu , the new moon brings it): The priest Neferibed: Praise Amun, kiss the earth to the lord of the gods, at his first festivals of the season Schemu, when he lights up on the day of the journey to the valley Neb-hepet-Res on the part of the Amun priest Neferibed. "

Later corner stone tablets mention the names of Mentuhotep II and Hathor. The procession of the then valley festival could be dated to the last third of the reign of Mentuhotep II. At the beginning of the festivities, the priesthood transported a statue of Amun-Re from the temple of Karnak to the divine royal boat in order to reach the valley of Mentuhotep II. The inscription of a priest from el-Qurna on the name of the valley festival has been preserved on a grave stone from the Middle Kingdom : "May you receive breads of sacrifice from Amun on his beautiful feast of the rowing trip ".

Similar phrases were used later in the New Kingdom. So also on a memorial stone of Amenhotep III. : "His father Amun, who takes the rowing trip into the valley to see the gods of the west." From other different names of the valley festival as "Coming of the god Amun from Karnak" or "his beautiful festival from the desert valley" it becomes evident that the name of the valley festival was derived from the destination of the Amun journey. The special Hathor cult in the valley of Mentuhotep II probably caused Queen Hatshepsut to have her mortuary temple built there as well.

New kingdom

From the 18th dynasty , Amun-Re in its special form as "King of the Gods" changed the date of the festival, which the Egyptians now celebrated in the second Schemu month under the name "Beautiful festival of the valley of Amun-Re" and for two days extended. Around 1500 BC Because of the dependence on the new moon, the beginning of the valley festival fell between mid- May and mid- June . The Amun's journey was intended for the "goddess Harthor, whom Amun visited on the west side of Thebes to stay the night with her". The boat crossing therefore of Amun was up to the 19th dynasty traditionally held even without the company of other gods.

The symbolic "train to Chemmis" association Hatshepsut with the celebrations of the Talfestes. After her ritually performed “birth” the procession went to the mortuary temple of Hatshepsut . There Hatshepsut united with the cult image in the Hathor shrine to be later elevated to Hathor. Since she could not be the "Horus boy" as queen, Hatshepsut probably referred to himself as the "(female) child of Hathor" for this reason.

The "valley festival" was one of the calendar-based "renewal festivals" that were organized for the respective kings in order to confirm the king's function as representative of the deity "Amun-Re". As part of the celebration of the valley festival, a processional trip to Deir el-Bahari took place. Thutmose III. moved the festival during his reign to his mortuary temple, which was between the facilities of Mentuhotep II and Hatshepsut.

After his death, the celebrations were mostly held in the area of the mortuary temple of Hatshepsut. With the beginning of the accession to the throne by Amenhotep IV, the celebrations were suspended during his reign until his successor Tutankhamun . From the grave inscriptions of Neferhotep it emerges that under Eje II at the latest the mortuary temple of Thutmose III. Was the focus of the processions.

In the Tomb of the Night , an official of the 18th Dynasty, the private festivities within the framework of the festival are impressively reproduced and have been preserved to this day.

Valley festival dates

The dependence of the valley festival on the Sothis lunar calendar could lead to overlaps with the main festival dates, which were linked to the administrative calendar with a fixed date . Due to the fact that the date had been changed since the New Kingdom, the earliest possible date of the valley festival in the administrative calendar fell on the 26th Schemu I ( 26th Pachon ); the last possible start on the 26th Schemu II ( 26th Payni ). In the event of overlapping dates, the younger party was postponed to another date. Ramses III. noted in his festival calendar two reserved holidays for the valley festival:

“What is sacrificed to Amun-Re, the king of the gods, as a festival service for his festival of the valley, which falls in the second month of the Schemu season. The new moon day brings it. On this day and the next (after the new moon) this glorious God rests in the house of millions of years of King Ramses III. in the district of Amun. "

The table below lists the dates that have been preserved on papyri and that could be assigned to the respective kings. The note from Tausret is striking : 28. Schemu II, as Amun-Re rested in the mortuary temple of Sat-Ra-meri (t) -en-Amun, king of Upper and Lower Egypt , in the temple of Amun in the west of Thebes . Since the 28th Schemu II could not possibly mark the normal beginning of the valley festival, it had to be either a third holiday or a postponed date of the valley festival. The exact whereabouts of Amun-Re also remains unclear, as the mortuary temple of Tausret in West Thebes between the complexes of Thutmose IV and Merenptah could not be completed due to the short reign.

| Valley festival | ||||

| king | source | Egypt. calendar | date | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ramses ii | Graffito DB 32 | 20. Schemu II | April 8, 1268 BC Chr. | Government year 12 |

| Thaw | Graffito DB 3 | 26. Schemu II | March 27, 1191 BC Chr. | Government year 7 |

| 19th dynasty | Ostraca Cairo 25538 | 23. Schemu II | ? | Return of Amun 25th Schemu II |

Festival character until the Amarna period

"Nice festival of the valley of Amun-Re"

The celebrations for the "beautiful festival of the valley of Amun-Re" were a special event of the year in addition to the Opet festival introduced in the New Kingdom , the procession of which made an impressive spectacle with participants from the king's family, the priests and officials must and, above all, had a very lasting effect on contemporaries.

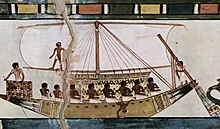

Priests in their white robes carried a barge with the statue of Amun, which stood in a closed wooden shrine on a pedestal, from the Karnak temple in the procession on carrying poles ; the priesthood pulled the boat with the hull moored on a sledge to pull it across desert sand . The king, dressed in a gala apron and double crown , led the procession and accompanied the imperial god Amun on his annual trip with the statues of the deceased kings. On the way to the bank of the Nile stood the divine station stamps, in which places were built for the worship of the kings for the cult of the dead. Only during the valley festival celebrations did Amun return to those innermost rooms of the station temple on “his feast day in the city of the dead”.

After completing these visits, the procession made its way to the landing site on the Nile, where the Amun statue was loaded onto the divine “Barque Userhat Amun ”. In tow of the royal ship, the Userhat Amun set off for the west bank, surrounded by a convoy consisting of several boats. With the beginning of the 19th dynasty, images of the crossing to Westtoben appear in the graves for the first time. The accompanying barges of the deities Mut , Chons and Amaunet are also only attested from the 19th dynasty. On channels of the procession finally reached the location at the edge of the desert land site located in the immediate vicinity of a royal mortuary temple was located. None of these magnificent barques have survived, but they are known from representations. They were made of fine wood and decorated with gold and silver. After the Amun statue had been reloaded from the boat onto the carrying bars, the priesthood solemnly transported the image of God to the temple.

From the festival calendar of Medinet Habu it is known that the statue of Amun only rested on the nights of the two-day festival between burning torches in the holy of holies of the royal mortuary temple. The torches were firmly anchored in four artificial stone ponds. After the vigil, the priesthood ritually extinguished the torches with freshly milked milk. From there the first way led in a solemn procession into the valley basin of Deir el-Bahari to those royal mortuary temples for which a cult was still performed . There the king and the priesthood made sacrifices to the deceased kings, queens, royal mothers, high temple officials and the spirits of the dead of the cemetery .

At the time of Ramses II , the procession made its way to the Ramesseum . Here the statues were brought into the sanctuary of the temple. The gods of protection of the dead, especially the deified King Amenhotep I , were worshiped here. He was the god of the necropolis workers who lived on the west side in Deir el-Medina . According to the Egyptians' imagination, not only the living came, even the dead are said to have rushed to the festival to see Amun-Re. Animals, frankincense , myrrh and huge bouquets of lotus , papyrus and other flowers were sacrificed .

"Fest im Grabe" as a dance and drinking festival

The "Fest im Grabe" was a supplement to the Talfest festivities, but had no direct reference to the Talfest itself. The typical character traits of a dance and drinking festival, which were only shown during the 18th dynasty, corresponded to customs that were also part of other drunkenness festivals , such as the New Year festival . The “feast in the grave” began in the morning and lasted through the following night until the symbolic morning greeting to Amun at sunrise on the next feast day. It ended shortly afterwards when the priesthoods began to leave and returned to the Karnak temple with the statue of Amun.

At the beginning of the official celebrations, all people who had buried relatives in Westthebear were already standing at the graves of their ancestors to make sacrifices and celebrate there. On the mountain slopes, however, the population only assumed an observing position of the ritual celebration of the valley festival, which also explains why images of temple rites and the processional procession are missing in the grave representations. After the Amun's boat trip, delegations of priests climbed the mountainside, accompanied by the choirs who had previously sung about Amun's crossing of the Nile. Together they went through the city of tombs and greeted those present and presented bouquets of flowers as a token of love, thanks and favor of the deity Amun.

The large bouquets of flowers, some as tall as a man, were already eye-catching during the procession. They were considered the epitome of life that was carried into the city of the dead in this way. In the meantime, the grave owners had their servants brewing the festive drinks or having various wine mixes made. Around the same time, hired musicians arrived, who now played to dance. The festival participants saw this one-day ceremony as "something that is done for the deity". This meant Amun in particular, as can be seen from a sacrificial prayer:

“For him (Amun) one brews on the feast day and stays awake in the beauty of the night. His name circles on the roofs. He owns the singing at night when it's dark. "

The celebration showed clear characteristics of a drinking binge . The drunkenness associated with the festival was a natural part of it. The Egyptians repeatedly filled the wine into smaller jugs from the barrels provided , from which it was continuously poured into cups and bowls. The guests of the grave can be seen in pictures either sipping the drink or drinking to the full. The uninhibited drinking pleasures ended mostly in the final intoxicated unconsciousness, which was also contents of the grave representations.

The mythological background was the idea of increasing joie de vivre and enjoyment to the limit of the possible in the realm of the dead. This form of celebration was not possible without noise, dance and exuberance. The motto was accordingly: "Drink and celebrate the beautiful day". A typical example of the joy of drinking is the saying of a daughter of the tomb lord on a shrine , whereby the Egyptians understood the tomb on the day of the valley festival as the "house of joy in the heart" of the living and the dead:

“Your Ka , drink the nice binge, celebrate a nice day with what your Lord (Amun-Re) has given you, the God who loves you. Great one who loves the wine, which is praised for myrrh , you do not stop to refresh your heart in your beautiful house. "

The fixed component of drunkenness is mainly due to the traits of the goddess Hathor, as she was regarded as the "mistress of the desert mountains" and "mistress of drunkenness". In the “Myth of the Celestial Cow”, the destruction of mankind by Hathor as the eye of Re could only be prevented by the ruse of “appeasing by administering a mixed drink”. For Thebes , the month of the valley festival is expressly stated for this occasion. In the calendar of the entrance area of the Temple of Mut in Karnak it says: "You are flooded with the red beer at the time of the valley festival [...] to appease your heart in your resentment". Presumably similar rites were performed in the temples to celebrate Amun's visit to Hathor and the joys of the drinking party that followed.

From the grave of Menna , which was laid out under Thutmose IV in Sheikh Abd el-Qurna , an offering prayer to Amun-Re has been preserved in an inscription from the entrance area for the valley festival :

“Let me see you at your beautiful party, at your rowing trip from Djeser-djeseru . Your wonderful light on my body. Then I praise you, your beauty before my face. May you let me rest in the house (grave) that I built for myself through the favor of the good God (Thutmose IV.); may you let me be among your entourage, happy with the bread you give, as it happens to the righteous on earth. "

"Train to Chemmis"

In the pyramid texts , Chemmis is mentioned as the birthplace of Horus. With reference to the deceased king you can read: "Your mother Isis gave birth to you in Chemmis, you receive your hands, which belong to the north wind". Further reports can be found in the coffin texts : “Oh people, see this king, the son of Isis. He was conceived in Buto and born in Chemmis ”. The background was the mythological idea that the young Horus stayed at the secret place Chemmis in order to grow into a man hidden from Seth of Isis .

Hatshepsut sees himself as a "Hathor child" who was protected by Isis: "I went through the swamps and settled in Chemmis as protection." About the cult act performed by Hatshepsut can be read: "Hathor, she has the birth repeated. They arranged (probably the king) that Hatshepsut settled in her mortuary temple ”. Once there, the cult image in the Hathor shrine was animated by sacrifices. Hathor was thus able to perform the acts of protection and suckling as Mother of God after the birth of the Horus boy in Chemmis. In this respect, the procession of the "Chemmiszug" connects the birth and the chemmis actions.

After Hatshepsut's appointment, the mythological term “ Horus in Chemmis ” is often used in royal inscriptions as the legitimacy of the government's claim to the “Horus throne of the living”: “His majesty was still a boy like the child Horus in Chemmis, in that his beauty was like his who protects his father ”.

Amarna and the time after

Under Akhenaten his ended by introducing Aton - cult celebrations of Talfestes until his death. The Amarna period had a direct influence on the later festival character. However, it should be emphasized that the teachings of Akhenaten did not bring any ideological changes for the valley festivals after the Amarna period, but only affected the external appearance.

Amarna time

With the elevation of Aton as the only life-giving deity, the notion of a life after death in the duat came to an abrupt end. Akhenaten's theology was unable to give an answer to what happens to the dead after death. This break with previous beliefs marked the hour of birth of the “new harpist songs ”, the content of which was based on the Middle Kingdom and at that time embellished isolated thoughts about death in a new poetic framework.

The harper song of the Antef is considered a classic model for all later harp song versions, which, as variations of this song, found central entry into the belief in the dead. The harper song of the Antef comes from the Amarna grave of Pa-Atonemheb and refers to the meaning of life:

“Those who built houses there, their place is no more. What happened to them? I have heard the words of Imhotep and Hordjedef , whose sayings are on everyone's lips. Where are their places? Their walls have crumbled, they no longer have a place as if they had never been. Nobody comes from there to report on their progress and to calm our hearts. But you delight your heart. It is good for you to follow your heart. Dress in white linen and increase your beauty, do not let your heart get tired of it. Don't hurt your heart until the day of the mourning comes. Celebrate the beautiful day, don't get tired of it. Refrain : Remember, nobody takes with them what they are attached to; no one returns who has gone once. "

The time after Amarna

The renaissance of the valley festival took place under Haremhab and the kings of the 19th dynasty . Even if the Aton cult disappeared, its message of openness and the "showing of reality" remained in the minds of the Egyptians. Before Akhenaten, it was customary in the Amun Re cult to only think about death in personal dialogues. In the valley festival, however, the Osirism myth determined the content. The Amarna period caused a reversal of the earlier conditions: Horus and Osiris took a back seat, while Isis , Hathor and Nephthys, as "mourning mothers for the dead", gave the valley festival a rather sad mood. The formerly lived "carelessness of Horus" gave way to the "Isis Lament".

In the graves of the time after Ramses IV , the representations show that the character of the valley festival changed noticeably. The decline and the associated chaos of the expiring 20th dynasty ensured that the "Isis Lament" was overemphasized. The Egyptians believed that they could restore the former stability of their country with particular piety . Instead of depictions of life, only scenes of sacrifice , transfigurations and books from the underworld adorned the walls. Earlier pictures of naked dancers in older graves were mostly painted over or made illegible. The "Isis Lament" was now followed by the "victim attitude in the hope of better times".

The valley festival was still celebrated during the reign of the first Roman emperor Augustus (27 BC – 14 AD). Augustus had on September 2, 31 BC The forces of Mark Antony and Cleopatra VII were defeated in the 2nd century BC and Alexandria was taken in the following year , whereby Egypt lost its independence and was annexed as a new Roman province . On the occasion of the valley festival, the Roman emperor formulated his wishes for the dead:

“May you come out and enter the necropolis of Thebes without your step being hindered in its cemetery. May you stand in the area to the west of Thebes on that day of the water voyage. May you see the riverboat Userhat with its jewelry. The God of gods is alone in him. May you hear the shouting of the king's rivermen when the king's ship goes down the river. May you see in him the King of Upper Egypt as pilot , the King of Lower Egypt in driving his helm . May you see the King of the Gods in his great mystery, the Father of the Gods in his glorious form. May you go to the Lord of the Gods in the temple among the blessed at the valley festival. "

Death of Ramses III.

A papyrus from the time of Ramses IV describes in detail a trial that involved a palace intrigue against Ramses III. went. The retrospective reports on the palace intrigue are undated, contrary to normal practice. The connection between palace intrigue and the death of Ramses III. In the 32nd year of government, Egyptology is the subject of controversial discussions. The date of death 15th Schemu III (April 7th) 1156 BC. Chr. Is to be regarded as safe, since it is documented several times. It fell on the first holiday of the festival of sacrifice for the deities Amun-Re and Hapi. The occasion of the ceremony, which was celebrated near his mortuary temple , left Ramses III. write on a stele : May Amun-Re and Hapi see to it that the Nile does not lack water to hide the glories of the Duat . Some Egyptologists nevertheless suspected the celebrations of the valley festival as the time of the attack, since it was the last recorded festival in contemporary sources.

In order to be able to establish a connection to the valley festival, James H. Breasted and Hans Goedicke drafted the speculative thesis that Ramses III. the palace intrigue survived seriously injured for 21 days. Accordingly, the attack would be on 23/24. Schemu II happens, which requires a valley festival date around the 21st Schemu II. Neither Breasted nor Goedicke could give evidence or evidence for this assumption. Erik Hornung and Wolfgang Helck refuse due to the long period between the beginning of the festival and the death of Ramses III. and because of the lack of evidence, the theory of a Talfest palace intrigue in the 32nd year of government.

Rolf Krauss , who also dealt with the various assumptions, sees the possibility of a Talfest context only if the Minfest , which took place a month before, was postponed together with the Talfest. Like the Talfest, the Minfest was also tied to the lunar calendar , which is why a postponement can be excluded under these circumstances. Rolf Krauss also refers to the content of a graffiti from the seventh year of Ramses III's reign. with the there for the 9th Schemu III. documented offerings to Amun-Re. Since the lunar dates in the ancient Egyptian lunar calendar are repeated every 25 years, in the 32nd year of Ramses III's reign, contrary to the assumption of Breasted and Goedicke, the 9th Schemu III. again as a holiday in connection with the deity Amun-Re part of a ceremony.

Rolf Krauss comments on the above-mentioned offering of the 9th Schemu III that the valley festival is not mentioned in the information about the seventh year of the reign and that it could be a different festival. Siegfried Schott sees in the 9th Schemu III ( 9th Epiphi ) the date of the coronation feast of Amenophis I in Deir el-Medina , the 1181 BC. BC and 1156 BC BC also began on this day.

| Valley festival dates in the lunar calendar at the time of Ramses III. | ||||

| year | source | Egypt. calendar | date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 31st year of government | Civil lunar calendar | 21. Schemu II | March 14, 1157 BC Chr. | |

| 32nd year of government | Civil lunar calendar | 9. Schemu II | March 2, 1156 BC Chr. | |

See also

literature

- Jan Assmann : Death and the afterlife in ancient Egypt. Special edition. Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-49707-1 .

- Erhart Graefe : Valley Festival. In: Wolfgang Helck : Lexicon of Egyptology. Volume 6: Stele - Cypress. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1986, ISBN 3-447-02663-4 , pp. 187-189.

- Erik Hornung : Studies on the chronology and history of the New Kingdom (= Egyptological treatises. (ÄA). Vol. 11, ISSN 1614-6379 ). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1964.

- Rolf Krauss : Sothis and moon dates. Studies on the astronomical and technical chronology of ancient Egypt (= Hildesheimer Egyptological contributions. (HÄB). Volume 20). Gerstenberg, Hildesheim 1985, ISBN 3-8067-8086-X .

- Siegfried Schott : The beautiful festival of the desert valley. Festive customs of a city of the dead (= Academy of Sciences and Literature. Treatises of the Humanities and Social Sciences Class 1952, Volume 11, ISSN 0002-2977 ). Publishing house of the Academy of Sciences and Literature, Mainz 1953.

- Siegfried Schott: Altägyptische Festdaten (= Academy of Sciences and Literature. Treatises of the humanities and social science class. (AM-GS). 1950, Volume 10). Publishing house of the Academy of Sciences and Literature a. a., Mainz u. a. 1950.

- Abdel Ghaffar Shedid , Matthias Seidel : The grave of the night. Art and history of an official grave of the 18th Dynasty in Thebes-West. von Zabern, Mainz 1991, ISBN 3-8053-1332-2 , pp. 17, 27.

- Magdalena Stoof : The hundred-goal Thebes (= accent. Volume 80). Urania, Leipzig / Jena / Berlin 1986, ISBN 3-332-00066-7 , pp. 77-79.

- Martina Ullmann: Thebes. Origins of a Ritual Landscape. In: Peter F. Dorman: Sacred space and sacred function in ancient Thebes (= Studies in ancient oriental Civilization. Volume 61). Occasional proceedings of the Theban workshop. Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, Chicago IL 2007, ISBN 978-1-885923-46-2 , pp. 3-25.

- Silvia Wiebach: The meeting of the living and the dead as part of the Theban Valley Festival. In: Studies on Ancient Egyptian Culture. (SAK). Volume 13, 1986, ISSN 0340-2215 , pp. 263-291.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Martina Ullmann: Thebes. Origins of a Ritual Landscape. Chicago IL 2007, pp. 7-8.

- ^ A b Adolf Erman , Hermann Grapow (Ed.): Dictionary of the Egyptian language. Volume 1. Hinrichs, Leipzig 1926, pp. 93, 9.

- ↑ a b c Siegfried Schott: The beautiful festival of the desert valley. Mainz 1953, pp. 76-77.

- ^ A b Siegfried Schott: The beautiful festival of the desert valley. Mainz 1953, p. 125.

- ^ Siegfried Schott: Ancient Egyptian festival dates . Mainz et al. 1950, p. 71.

- ^ A b c d e Rolf Gundlach, Matthias Rochholz (ed.): Egyptian temples - structure, function and program (= Hildesheimer Egyptological contributions. Vol. 37). (Files from the Egyptological temple conferences in Gosen in 1990 and in Mainz in 1992). Gerstenberg, Hildesheim 1994, ISBN 3-8067-8131-1 , pp. 67-68 and 75.

- ^ A b Siegfried Schott: The beautiful festival of the desert valley. Mainz 1953, p. 85.

- ^ A b W. Helck : History of Ancient Egypt (= Handbook of Oriental Studies . Department 1: The Near and Middle East. Volume 1: Egyptology. Section 3). Brill, Leiden u. a. 1968, pp. 198-199.

- ^ W. Helck: History of Ancient Egypt (= Handbook of Oriental Studies. Division 1: The Near and Middle East. Volume 1: Egyptology. Section 3). Brill, Leiden u. a. 1968, pp. 93-97.

- ^ HE Winlock : The rise and fall of the middle kingdom in Thebes. Macmillan, New York NY et al. a. 1947, Figure 40, I. and P. 79ff .; German translation: Siegfried Schott: The beautiful festival of the desert valley. Mainz 1953, p. 94.

- ↑ Siegfried Schott: The beautiful festival of the desert valley. Mainz 1953, p. 94.

- ↑ a b c d Siegfried Schott: The beautiful festival of the desert valley. Mainz 1953, pp. 5-7.

- ^ Siegfried Schott: Ancient Egyptian festival dates. Mainz et al. 1950, p. 105.

- ↑ Abdel Ghaffar Shedid, Matthias Seidel: The grave of the night. Mainz 1991, p. 17.

- ^ Siegfried Schott: Ancient Egyptian festival dates. Mainz et al. 1950, p. 107.

- ↑ a b Conversion to today's Gregorian calendar .

- ↑ Siegfried Schott: The beautiful festival of the desert valley. Mainz 1953, p. 8, valley festival ritual according to BM 10209.

- ↑ a b c Siegfried Schott: The beautiful festival of the desert valley. Mainz 1953, pp. 92-93.

- ↑ Siegfried Schott: The beautiful festival of the desert valley. Mainz 1953, p. 94.

- ^ A b Jan Assmann: Death and Beyond in Ancient Egypt. Munich 2003, pp. 193–194.

- ↑ Jan Assmann: Death and Beyond in Ancient Egypt. Munich 2003, pp. 195–196.

- ↑ Siegfried Schott: The beautiful festival of the desert valley. Mainz 1953, p. 96.

- ↑ a b c Rolf Krauss: Sothis and moon dates. Hildesheim 1985, p. 143.

- ^ Siegfried Schott: Ancient Egyptian festival dates. Mainz et al. 1950, p. 109.

- ^ W. Helck: History of Ancient Egypt (= Handbook of Oriental Studies. Division 1: The Near and Middle East. Volume 1: Egyptology. Section 3). Brill, Leiden u. a. 1968, pp. 200-201.

- ↑ a b Rolf Krauss: Sothis and moon dates. Hildesheim 1985, p. 138.

- ^ Siegfried Schott: Ancient Egyptian festival dates. Mainz et al. 1950, pp. 109-110.