Battle of Breitenfeld (1631)

Frankfurt (Oder) - Werben - Breitenfeld - Rain - Wiesloch - Zirndorf - Lützen - Hessisch Oldendorf - Regensburg - Nördlingen

| date | September 17, 1631 |

|---|---|

| place | Breitenfeld , a few kilometers north of Leipzig |

| output | All-out victory for the Swedes |

| consequences | Sweden becomes a major military power |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

|

Catholic League |

Sweden, Saxony |

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| 32,000, 30 guns | 42,000, 70 guns |

| losses | |

|

12,000 dead, |

4,000 dead |

The battle at Breitenfeld of 1631 between a Swedish-Saxon army and the army of the Catholic League took place on September 18, 1631, one year after Sweden intervened in the Thirty Years War and only a few days after the conclusion of an alliance between Sweden and the Electorate Saxony. The site of the battle is north of Leipzig between the villages of Breitenfeld and Seehausen . The army of the Catholic League suffered a heavy defeat.

course

Developments before the battle

The army of the Catholic League, under which there was League Army Leader Tilly , had conquered the Pleißenburg fortress on September 14th , then extensively plundered it in the city of Leipzig and made great booty. As a camp for the army, Tilly chose an elevated area near the city, which offered the guarantee that it could not be attacked there. While exploring the area, the deputy of Tilly and leader of the league cavalry Pappenheim discovered the field camp of the Swedish army with his cavalry troops on September 16 and was involved in a battle from which he could not escape safely. Pappenheim, who tended to spontaneous, rash actions and considered Tilly hesitant, incompetent and senile, asked Tilly with a messenger to support him and his cavalry troops wherever he stood against the enemy. But Tilly had followed a different schedule and was expecting the reinforcement of his army by Johann von Aldringen's corps returning from Mantua . Tilly, who was very angry about Pappenheim's arbitrariness, decided nevertheless to follow Pappenheim's request. He moved with the army to the desired location near the village of Breitenfeld, 6 km north of Leipzig, had the League army with 40,000 men camped there and took an advantageous, slightly elevated position on an elongated open plain.

Lineup

In the early morning of September 8th jul. / September 18, 1631 greg. When the united Swedish- Saxon army approached, it met the League Army that had already been formed and began with the formation. The army was led by King Gustav Adolf of Sweden and Elector Johann Georg and, with around 47,000 men, was clearly superior to the League Army by around 10,000 men and in terms of artillery.

The formation of the league army was carried out in the tradition of the conventional orderly (battle order) and had resulted in a front about 4 km long, with sun and the wind in the back, so that the Swedish-Saxon troops were disadvantaged with the prevailing high temperature .

- Foot troops in the center (approx. 25,000 men) formed in approx. 15 violent piles (30 rows in a row of 50 men, pikemen and musketeers)

- Cavalry massed, with 5,000 men on each wing.

The formation of the Swedish-Saxon army was approx. 5 km long and not uniform because of the different traditions of the two armies.

- The Saxon cavalry headed by Elector Johann Georg was massed on the left wing and formed a splendid sight with their beautiful uniforms.

- In the middle, Saxon infantry joined the Swedish infantry.

According to the battle rules adopted by Gustav Adolf , the Swedes relied on a mobile battle, which required a completely new type of organization and a wide range of troops. Because of improved weapon technology, a close, well-coordinated interaction of various weapons had become an essential part of the new order of battle among the Swedes. The number of pikemen had been reduced to a third in favor of the musketeers , which meant that hand-to-hand combat had lost its importance in favor of the musketeers' gunfight. In order to achieve a faster rate of fire, the Musketeers were set up in squadrons only six men deep with the first row kneeling so that the two front rows could fire at the same time and then switch to the rear at the same time to reload when moving forward again. This gave the musketeers a decisive role in the battle and therefore the procedures and reloading were practiced by the mercenaries through enormous drills. The firepower of the Swedish infantry proved to be three times more effective than the League troops and was further increased by lightweight portable companion guns, in addition to balls and grapeshot fired to smash enemy on shortest distance formations.

- Instead of massing the Swedish cavalry on the right wing, small groups of riders were formed with freedom of movement on all sides.

- Between the groups of riders there were square groups of musketeers and pikemen with only 6 rows in a row of 50 men.

The checkerboard type of formation made the Swedish army much more stable against attacks from different sides. This was already evident in the first phase of the battle, when the league cavalry under Pappenheim tried to circumvent the Swedish army on the right wing and attack the reserve troops in the rear. This cavalry attack could be repulsed by Swedish horsemen, reinforced by accompanying musketeers, who were immediately on the spot and preferred to shoot enemy horses.

The heavy artillery remained with the reserve for massive fire summaries.

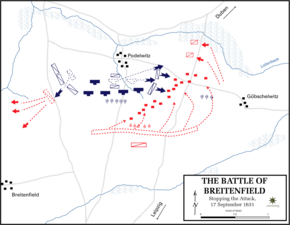

The battle took place in three phases: the attack of the League troops, their advance to the northeast and their encirclement and destruction by the Swedes.

Course of the battle

1st phase

Even at the beginning of the battle, the artillery and muskets fighting that lasted several hours until the early afternoon proved the superiority of the Swedish gunners and musketeers, who responded to a volley of the league troops with three to five volleys from their barrels. In the early afternoon, starting from the left wing of the league, after extensive bypassing, a cavalry attack from Pappenheim on the right wing of the Swedes, which initially appeared to be successful. There the attack met the combined defense of musketeers, infantry and cavalry, with the Swedish musketeers mainly concentrating on shooting down the attackers' horses and then retreating into the protection of pikemen. The engagement spread to the west in a mutual attempt to outflank the enemy. At the end of his advance, the Pappenheim riders found themselves surrounded and only escaped with difficulty.

2nd phase

In view of the fierce fighting that had developed from Tilly's point of view on the left flank between the league cavalry troops under Pappenheim and Swedish troops, Tilly seized the chance, at the time when the Swedes were bound in full battle, with four Tercios at the same time also to attack the other wing of the opposing troops where the Saxon regiments and the Saxon artillery were set up under the command of Arnim and Klitzing . The recently recruited and inexperienced Saxon mercenaries had bravely withstood the bombardment for the past few hours, but then came under such heavy fire during the attack by the Tercios that a bloodbath was wreaked in the first row and the next rows wavered. The wavering gradually turned into an escape movement when the Croatian cavalry of the league troops, led by Palant and Holck , led the final attack with a deafening noise and a cloud of dust. The Saxon gunners were the first to flee. Their cannons were taken over by the attackers and aimed at the Saxon cavalry. Elector Johann Georg, as leader of the cavalry, took this as an opportunity to turn his horse and flee from the battlefield to Eilenburg, 20 km away . Even the commander of the Saxon army Arnim could not stop the escape of the Saxon cavalry and the foot troops after the elector's flight. The fugitives did not fail to loot the Swedish supply wagons when they passed the rear area.

Tilly used the escape of the Saxon troops and set the league infantry on the march diagonally to the front line in the direction of the wavering, partly already disbanded opposing wing. There the advancing imperial cavalry was even able to penetrate into the rear of the Swedish troops at times, and the victory of the league troops, which had become unlikely after the first phase, was now within reach. For the Swedish army began a decisive phase in which it - now outnumbered - had to withstand the concentrated force of the attacks of the league army. However, the Pappenheim League cuirassiers and their horses were severely decimated and quite exhausted after the initial fighting on the Swedish right wing, as they had not been supported by musketeers there. In contrast, the Swedish equestrian musketeer squares were stable like rocks between which the league riders were exposed to the musketeers' fire.

In addition, Gustav Adolf had arranged so-called second meetings according to the meeting tactics anchored in the Orange Army Reform . These were troops committed to supporting the first meeting and now able to intervene. These troop units now intervening were the freshest units on the field and were supported by external conditions that had changed in the evening. The low sun, which had previously blinded the Swedish attackers, had disappeared. The wind had turned and the dust, the biggest evil of the day, was no longer blown in the faces of the Swedes, but of the League troops. The following troops were now deployed:

- General Banér and his light cavalry (Finns and West Goths) as well as his heavy cavalry (Smalanders and East Goths) counterattacked and scattered the remains of the Pappenheim cuirassiers in the direction of Halle (Saale) .

- Because of the threatening situation on his left flank, Gustav Adolf ordered the leader of the 2nd meeting, General Horn , to swing his infantry troops at a right angle to the east and thereby separate the league cavalry from the foot troops.

- Lennart Torstenson, commander of the Swedish artillery, took fire from the flank of the league infantry advancing in clumsy Tercio formation to pursue the fleeing Saxons. Pressed by the Swedish artillery fire and continuous cavalry attacks, the Tercio formations had to break off the attack and go over to their own defense.

3rd phase

With the advance of the Swedish infantry to the northeast, the Saxon cannons were recaptured and the center of the imperial troops with its artillery positions increasingly weakened. Gustav Adolf therefore regrouped the Swedish cavalry: the Hakkapeliitta , the Finnish light cavalry, stormed the central artillery positions of the enemy under the personal leadership of the king, followed by the heavy cavalry under General Banér and three infantry regiments. Tilly no longer succeeded in aligning the outmaneuvered Tercios on the new enemy and in addition the Swedes now directed the captured artillery on the imperial troops and took them under fire from several sides. Pursued by Swedish troops, the league troops began to flee. Tilly was wounded, fell from her horse, was able to get up again, but passed out after a second wound. Under cover of the falling darkness he was rescued and reached Halle the next morning with only 600 men . Pappenheim stayed behind on the battlefield, got into a difficult battle of retreat and tried to save the remains of the army. When it got dark he was able to repel his pursuers and initially reached Leipzig with four regiments. He could only stay there until the next morning and then moved on to Halle.

Military strategic consequences

The League Army, supported by the Emperor, and thus the Catholic side, had suffered their first major defeat in the 13-year war. The heavy losses of the Imperial League Army on the battlefield increased as the surviving remnants of the army flee. An innumerable number of fleeing and deserted mercenaries of the Catholic League Army were hunted down and slain by the Saxon population and groups of farmers. In this way the population took revenge for all the looting suffered by this army in the course of the previous years. Tilly, the most successful general on the Catholic side until then, had become a big loser. But despite the defeat and the losses, a few days later, 13,000 survivors gathered in Halberstadt, 100 km away, with whom Tilly immediately assembled a new army to protect Bavaria, which was now threatened by the Swedes.

For the Protestants, the great victory was a stroke of liberation and resulted in a flood of leaflets throughout the empire, which were intended to publicize the triumphant victory of the Protestants. The destruction of Magdeburg, which had triggered a protest storm by Protestants, had now been avenged and the edict of restitution threatening the Protestants had become worthless. The new tactics of a young Protestant king from Sweden had triumphed over the outdated tactics of an aged Catholic general. The captured 120 flags of the defeated regiments are still kept in Stockholm in the Riddarholm Church .

After the battle, the Swedish troops were numerically stronger than before, as 7,000 League mercenaries had moved as prisoners to the Swedish side. In the course of the following weeks, after the dukes of Mecklenburg, who were already allied with Gustav Adolf, many other imperial princes and imperial cities joined the Saxon-Swedish alliance. The influx of volunteers was so strong that seven Swedish armies with a total of 80,000 men could soon be formed, especially since France had promised the Swedes financial support.

On the other hand, the financial support of the imperial-Bavarian warfare was endangered by Spanish grants, because the supply of the Spanish troops on the Rhine had become insecure due to the Swedish control of the right bank of the Rhine. As a result of conflicts with Duke Charles IV (Lorraine) , an ally of the emperor, French troops had occupied Lorraine on the left bank of the Rhine without a declaration of war and were threatened by Spanish troops stationed there. The situation became especially precarious for the emperor when the two electoral principalities of Kurköln and Kurtrier refused to allow Spanish troops to march through and wanted to place themselves under the protection of France in order not to be occupied by the Protestant troops of the Swedish King Gustav Adolf.

After his overwhelming victory, the Swedish king began to drive out the Catholic bishops and to distribute the dioceses as gifts to his marshals on his incipient conquest. Thus it developed into a burden for Richelieu and for French politics, which was directed against the Habsburgs, but not against Catholicism and also not against Catholic Bavaria. In weeks of negotiations, French ambassadors tried in vain to set barriers to their ally, Gustav Adolf, to limit themselves to the occupation of northern Germany and to abandon the conquests on the Rhine and the planned advance into Bavaria. His two electoral allies in Saxony and Brandenburg also tried to make Gustav Adolf's peace negotiations palatable and to secure what had been achieved in the negotiations with compromises and not to jeopardize them. But his allies had also underestimated the Swedish king. Gustav Adolf wanted to continue the war and could even imagine running as a candidate in an imperial election. The fundamental differences in attitudes towards politics in the Holy Roman Empire meant that Gustav Adolf mistrusted both allies and the allies in turn soon dissolved their alliances with the Swedes after the death of Gustav Adolf (November 1632).

For Emperor Ferdinand II , the threatening development of the military situation after the defeat at Breitenfeld soon realized that a new army was needed and that could only be set up and led by Wallenstein , whom he had recently dismissed. After many letters of appeal from the emperor in November and December 1631, at the end of the year Wallenstein declared that he was ready to form a new army within three months. But he did not want to be responsible for the payment and receive further powers of attorney for himself.

Aftermath and commemoration

The overwhelming victory of the two allied Protestant armies of Sweden and Saxony was extremely important for the morale of the Protestant population and the Protestant imperial princes and imperial cities. In the course of the years after many defeats of Protestant armies, after the expulsion of the Danish king (1626) and the dukes of Mecklenburg by the Catholic armies of Tilly and Wallenstein, the Protestants had become the permanent losers. The imperial decree of the Edict of Restitution (1629) had put the crown on the development and with the permanent expropriation was supposed to fix the miserable situation of the Protestants.

Even the landing of the Swedish King Gustav Adolf with his army on the Baltic Sea coast (1630), which was celebrated by the Protestants, did not bring about the hoped-for rapid change in the situation, but initially the total destruction and depopulation of the arch-Lutheran city of Magdeburg . The city had immediately allied itself with the Swedes, but remained without comprehensive protection and was conquered and destroyed in May 1631 by troops of the Catholic League under Tilly. There was great indignation over the destruction and disappointment over the lack of help from the Swedes. The jubilation after the sweeping victory of the Swedes at Breitenfeld over the hated Tilly troops, which in the meantime had also begun to plunder Saxony, was all the greater three months later.

With the victory at Breitenfeld, Gustav Adolf acquired the reputation of the savior of German Protestantism . This call resulted in a broad movement in the veneration of Gustav-Adolf in the Reich. In eulogies and letters of praise, the character and achievements of this military leader were exclusively described positively, so that one can speak of a widespread Spanish rule . The designation of the king as a lion from midnight was widespread among the contemporary population and the fulfillment of a Paracelsian prophecy was assumed . In Erfurt, which was occupied by Sweden, Victory was celebrated on September 6 and 7, 1632 with a festival based on Jewish Purim , which corresponded to a Protestant interpretation that was widespread at the time. A commemorative thaler ( Purim thaler ) was also minted for the victory of the Swedish troops under Gustav Adolf and the reintroduction of Protestantism made possible by this. Maybe was Wilhelm Schickard 1634 derivation of the Christian Carnival of Joy Purim took place which also affected.

The saying "Freedom of belief for the world, saved by Breitenfeld, Gustav Adolf, Christ and Held" has been handed down in different versions . This saying was to be found on the monument erected in 1830 on the Breitenfeld battlefield. 200 years after the battle, the various anniversaries of the battle and the king were celebrated in Sweden and Germany. The cult of the king was broadly anchored. In Sweden, the bishop and poet Esaias Tegnér went so far as to describe Gustav Adolf Siege as a prerequisite for freedom of thought and science. The erection of the monument near Breitenfeld preceded the establishment of the Gustav-Adolf-Werk in Leipzig in 1832 . The battlefield near Lützen , where Gustav Adolf was killed, is only 25 km away in the Leipzig area. The strategic decisions made by Gustav Adolf at Breitenfeld were also widely discussed by the military, including Carl von Clausewitz .

swell

- anonymous: thorough and detailed report, like the king. Swedish, vnd Churf. Saxon. Army, with the Ligist or Tyllian Army, on Sept. 7th, anno 1631. at the Breitenfeld estate, a mile from Leipzig, met as it was everywhere with it, also like the Swedish and Saxons. Army received the Victoriam . Dresden 1631 ( digitized version )

literature

- Hans Delbrück : History of the art of war in the context of political history. Berlin 1920, part 4, pp. 232-240.

- AA Evans, David Gibbson: Military History from Antiquity to Today.

- Walter Opitz: The battle at Breitenfeld on the 17th IX. 1631 . Leipzig 1892

- Ernst Wangerin: The Battle of Breitenfeld on September 7, 1631 - a source investigation . Hall / S. 1896

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e C. V. Wedgewood: The 30 Years War . Cormoran Verlag, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-517-09017-4 , pp. 259-265.

- ^ A b Christian Pantle: The Thirty Years' War. When Germany was on fire . Ullstein Buchverlage GmbH, Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-549-07443-5 , p. 104-110 f .

- ↑ cf. Fiedler, Siegfried: Tactics and Strategy of the Landsknechte, Bonn 1985, p. 217ff and Orenburg, Georg: Waffen der Landsknechte, Bonn 1984, p. 133ff

- ^ Christian Pantle: The Thirty Years' War. When Germany was on fire . Ullstein Buchverlage GmbH, Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-549-07443-5 , p. 113-116 .

- ↑ a b c C. V. Wedgewood: The 30 Years War . Cormoran Verlag, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-517-09017-4 , pp. 2265-275.

- ^ Gustav II. Adolf: Gustav-Adolf-Werk Württemberg (relevant representation at the GAW). In: www.gaw-wue.de. Retrieved September 30, 2015 .

- ↑ Thomas Kaufmann: God's Victory at Breitenfeld and Adoration of Gustav Adolf, in Thirty Years' War and Peace of Westphalia: Church history studies on the Lutheran confessional culture . Mohr Siebeck, 1998, ISBN 3-16-146933-X ( limited preview in Google book search).

- ^ A b Thomas Kaufmann: Thirty Years' War and the Peace of Westphalia: Church history studies on the Lutheran confessional culture . Mohr Siebeck, 1998, ISBN 3-16-146933-X ( limited preview in Google book search).

- ^ Tyll Kroha (1977) Lexicon article "Purimtaler" in Lexikon der Numismatik. Bertelsmann Lexikon-Verlag. P. 347

- ↑ Dominik Fugger: Inverted Worlds ?: Research on the motif of ritual inversion, quoted by Ulonska 1998 . Walter de Gruyter, 2013, ISBN 978-3-486-72767-8 , p. 24 ff . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ A b Carl Zimmermann: The Gustav-Adolf-Verein: A word from him and for him. (With 62 illustrations) . Leske, January 1, 1857 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ a b Rikke Petersson: Back when Sweden was a great power -: Country and people at the time of the Peace of Westphalia . LIT Verlag Münster, 2000, ISBN 3-8258-4575-3 ( limited preview in the Google book search).

- ↑ a b c Sverker Oredsson: Historiography and cult . Duncker & Humblot, 1994, ISBN 3-428-48040-6 ( limited preview in Google book search).

Remarks

- ↑ The Aldringen corps, which was actually approaching, came close to Leipzig on the day of the battle and then had to be hidden from the victorious Swedish troops after the battle of Aldringen in the Thuringian Forest, which had meanwhile ended.

- ↑ Tilly said, “ This fellow is robbing me of my honor and the emperor for his country and his army. "

- ↑ Due to the lowering of the graduation depth, the Musketeers were also exposed to enemy fire for much longer, but this did not play a major role at the time

- ↑ "Meetings" are tactically related units that form a common front. Depending on their distance from the enemy, they are addressed as the first, second, etc. meeting. The first meeting is directly opposite the enemy, the other meetings are behind it according to the sequence of numbers.

- ↑ The Dukes Wilhelm and Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar as allied military leaders, the Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel , as well as August the Younger of Braunschweig, the Duchy of Württemberg , the Margraves of Ansbach and Bayreuth, the city of Nuremberg. The dukes of Mecklenburg