Battle of Cold Harbor

| date | May 31 - December 12 June 1864 |

|---|---|

| place | Hanover County , Virginia, USA |

| output | Confederation victory |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

|

Ulysses S. Grant

George G. Meade |

Robert E. Lee

|

| Troop strength | |

|

109,000108,000

|

59,00062,000

|

| losses | |

|

12,73813,000 killed

: 1,845 wounded: 9,077 missing / captured: 1,816 |

5,000

|

Wilderness - Spotsylvania CH - Yellow Tavern - Wilsons Wharf - Haws Shop - North Anna - Totopotomoy Creek - Old Church - Cold Harbor - Trevilian Station - Saint Marys Church

The Battle of Cold Harbor took place from May 31 to June 12, 1864 at a major intersection 15 kilometers northeast of Richmond , Virginia , during the American Civil War . In the same area, Confederate General Robert E. Lee had fought the Battle of Gaines Mill two years earlier during the seven-day battle against the Potomac Army , which he faced here again. The battle is therefore also called the Second Battle of Cold Harbor .

After heavy attacks on both sides in the first few days, Lee's Northern Virginia Army dug itself in, except for the cavalry, for defense and inflicted a heavy defeat on the outnumbered Potomac Army under Major General George Gordon Meade . The battle was the last major victory by a Southern Army during the war.

prehistory

Despite the Union's victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg , there was no progress in the eastern theater of war. President Abraham Lincoln still lacked an army leader who could end the war against the south as quickly as possible. In March 1864, for lack of other suitable generals, Lincoln appointed Major General Ulysses S. Grant, who had previously been successful in the Western theater of war, as Commander-in-Chief of the Army . Grant immediately began attacking the Confederation from all directions. He himself supervised the Potomac Army Major General Meade and James Army Major General Benjamin Franklin Butler on site, he Army Northern Virginia General Richmond immediately set against the Lees and the lines connecting the Confederate south in March. His goal was no longer the conquest of Richmond, as before, but the destruction of the opposing army.

“Lee's army will be your objective point. Wherever Lee goes, there you will go also. "

“Lee's army is your target. Wherever Lee goes, you will follow him there! "

he said to his generals.

The goal of the overland campaign

For the first time during the Civil War, Union warfare was in one hand. Grant commissioned Major General Sherman to advance into the deep south of the Confederation, while he himself wanted to bind and destroy Lee's Northern Virginia Army in Virginia. The annihilation of this army would lead to the fall of Richmond and ultimately to the collapse of the entire Confederation.

Grant intended to wage a war of attrition . In the battles to come, the superior Union armies would bleed Lee's Northern Virginia army to death. To achieve this goal, Grant attacked the Northern Virginia Army head-on in the Wilderness and Spotsylvania . Because he failed with this tactic, he tried to outflank Lee's army first at North Anna, then at Cold Harbor and finally at Petersburg.

On the eve of the battle - from Yellow Tavern to North Anna

After the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House on May 8, Lee intended to cut off Grant's path on his eastward march. To do this, he had his army in position on May 23 at North Anna so that Grant had to split his troops in order to attack.

Meanwhile, on May 9, Major General Sheridan and three cavalry divisions attacked the Northern Virginia Army depot at Beaver Dam Station and destroyed a locomotive and several wagons. On May 11, his advance was stopped by two cavalry brigades under Major General J. E. B. Stuart at Yellow Tavern . Stuart was fatally wounded during that engagement and Lee's nephew, Maj. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee, assumed command of the Northern Virginia Army cavalry. After four hours of fighting, Sheridan broke off the engagement and marched to the James to secure the left flank of the Potomac Army.

On May 24, Fitzhugh Lee marched with his cavalrymen on the left flank of the Potomac Army and attacked a Union depot at Wilson's Wharf, but was repulsed by colored regiments.

Grant divided the Potomac Army as Lee had foreseen; Lee missed the opportunity to beat Grant's corps individually and one by one for various reasons. On May 26, Grant began another attempt to outflank the Northern Virginia Army in the east.

The battle

Prelude - Am Totopotomoy

The Potomac Army crossed the Pamunkey at Hanovertown on May 28, under the protection of Sheridan's cavalry. Lee attempted to occupy a suitable position on Totopotomoy Creek in response to the movement of the Potomac Army. Lee sent one of his cavalry divisions for a violent reconnaissance of the Union Army. At Haw's Shop there was a seven-hour cavalry battle, both mounted and dismounted, which Lee used to dig himself into Totopotomoy Creek.

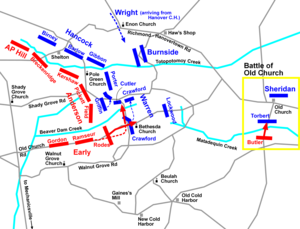

Grant let the cavalry evade and went on May 29th without reconnaissance against the position of the Northern Virginia Army from the east and north. Major General Hancock's II Corps attacked the Confederate positions, and the corps dug into it. By May 30th, Meade intended to outstrip Lee on both sides. This plan failed because Major General Wrights VI. Corps did not find the left end of the Northern Virginia Army and Maj . Gen. Warrens V and Maj . Burnsides IX. Corps did not attack with the necessary momentum.

Lee realized that two opposing corps south of the Totopotomoy Creek were isolated, and ordered Early's II Corps to attack and defeat the U.S. V Corps at Bethesda Church. Early asked Lieutenant General Anderson to support him with his 1st Corps. This support failed to materialize and the attack achieved little success.

Both armies faced each other in a stalemate. Grant therefore had his cavalry scouted south and east. At Old Church there was a mostly dismounted cavalry battle on Matadequin Creek, which the Northerners won because of their superior armament. The night ended the fighting; the Northern cavalry was within 2 km of the Cold Harbor junction.

Lee had reported to the War Department that afternoon that Maj. Smiths XVIII. Corps could threaten his right flank and rear after disembarking, and therefore asked for reinforcements by dawn of May 31st because of the withdrawal of the XVIII. Corps forces released by the James Army.

May 31st to June 2nd

Cold Harbor, not a port, but a rest house where only cold dishes were served, was located at a junction from which well-developed roads made it possible to move troops in all directions. Sheridan's Corps cavalry entered the intersection on May 31. During the day, Fitzhugh Lee, and later the infantry division arriving from James, tried to recapture Cold Harbor and got Sheridan in serious trouble. He therefore asked Grant to be allowed to evade, which he forbade him “ Hold on at all hazards ” (German: “Hold at any price”) and promised reinforcement by infantry for the next day.

The reinforcement requested by Lee arrived early in the morning and was deployed west of Cold Harbor. Lee then picked up the II., V. and IX. Corps on the right wing of the Potomac Army to force Grant to withdraw forces from Cold Harbor or prevent him from reinforcing there. The Union troops repelled all attacks by Early's II Corps. In the afternoon Grant therefore ordered II Corps to move to the left wing for the next morning. The VI was already on the march to Cold Harbor. and the XVIII. Corps.

During Lee's attacks on the right wing of the Potomac Army, VI reached the station on June 1 at around 9:00 a.m. Corps Cold Harbor, when Sheridan repelled the second Confederate attack by using his superior firepower. At around 2 p.m. the XVIII. Corps after a mad march and went right of the VI. Corps in position. Both should attack as quickly as possible. Due to the exhaustion of the troops, it was not until around 6:00 p.m. before the attack began.

Lee had responded to the movements of the Potomac Army and moved Anderson's I Corps to his right wing. The attack of the Union troops met buried infantry; they managed to break into the security line, but all attacks failed on the main line of battle . The Union troops now fortified the former enemy security line and held it against repeated night attacks by the Confederates.

Grant hadn't been able to win, but the paths to the crossings over the Chickahominy and to the James were in his hand. For June 2, Grant intended to attack with all five corps simultaneously and, depending on the success, roll up the Northern Virginia Army from either its left or right wing. The attack was initially planned for 5:00 p.m. However, the soldiers were so exhausted by previous fighting and the marches in heat and dust that the start of the attack was set for June 3 at 4:30 a.m.

The divisions on both sides began, if they had not already done so, to dig in. These positions no longer consisted of parapets, but were continuous zigzag-shaped trenches that stretched over a length of 7 km. In addition, connecting trenches were created in the depths of the positions, through which, on the one hand, the supply of those fighting in front was ensured and, on the other hand, units of the troops for counterattacks could be brought forward quickly and safely. Due to the shape, flanking fire on an attacker was possible at any time. The trenches were covered with wood to protect them from fire by the artillery and direct storming. Lee, his commanding generals, and the division commanders personally supervised the expansion of the field fortifications .

Grant's attack on June 3rd

On June 2nd and the night of the 3rd no one on the Union side had bothered to clarify the position and depth of the Confederate positions. The reason for this was a misunderstanding: Meade believed the corps had scouted and the corps believed the army had scouted. The soldiers of the Union were, however, well aware of what was in store for them in the frontal attack ordered. Many wrote their names on pieces of paper that they sewed into their uniforms so that they could be more easily identified in the event of death.

Punctually at 4:30 a.m., the II., VI. and XVIII. US Corps with a total of 31,000 men. The Confederates behaved in a disciplined manner and only opened fire with all weapons when the attackers were within range. The II Corps managed to break into the main Confederate line. This success was not exploited - either because the reserves were not there in time to stabilize what had been achieved, or because they were already being fought by Confederate units as they approached. The divisions of the II Corps had to evade and faced the Confederates in their former security line up to 40 meters away. The attack of the VI. Corps did not reach the main Confederate line. The gain in terrain brought their positions closer to those of the southerners. The XVIII. Corps quickly took the security line. All attempts to attack the main Confederate line failed, and the corps took up positions along the former enemy security line.

The attack by the three corps lasted less than half an hour and resulted in about 7,000 losses on the Union's part. One Union soldier recalled that members of his company went down and that he threw himself down too, believing there had been an order to do so. And his company commander was surprised because only a few rose again to comply with his attack command.

Each corps had attacked on its own responsibility. The attacks were not coordinated, and when the commanding general of the XVIII. Corps started his attack with the commanding general of the VI. Corps wanted to agree, this replied: "I'll just hit it!"

Grant realized around 7:00 a.m. that Confederate positions were stronger than expected and gave Meade the freedom to stop the attack where and then where it no longer seemed possible to succeed. Meade initially ordered the attacks to continue. Hancock refused to pass the order; Smith refused to obey. Wright's staff passed the order, repeated three times, without comment down to regimental level. Captain Thomas E. Barker, commander of the 12th New Hampshire Infantry Regiment (the regiment had already lost 164 of its 300 men in the first attack), said on receiving the order: “ I will not take my regiment in another such charge if Jesus Christ himself should order it! ”(German:“ I will not lead my regiment into another such attack, even if Jesus Christ should personally command it! ”). Many carried out the order to open fire on the Confederates from their positions but not to move towards the enemy.

On the right wing of the Potomac Army attacked the V and IX. Corps arrives punctually at 4:30 a.m. They managed to take the security line and break into the main Confederate line. Since artillery had to be brought forward for the further attack on the left wing of the Northern Virginia Army, the continuation of the attack was set at 1:00 p.m.

Around noon, Grant forbade any further attacks and ordered the Potomac Army corps to prepare for a siege. The soldiers dug themselves in, if they had not already done so, and improved their positions. That did not mean the end of the fighting - the artillery and sniper fire continued all day, causing further casualties.

That evening Grant admitted to his staff:

"I regret this assault more than any one I have ever ordered."

"I regret this attack more than any other I've ever ordered!"

Lee had used his advantage of the inner line on June 2nd and on the night of June 3rd to move troops and develop his position system. He had positions set up in the depths and distributed reserves so that they could quickly reinforce at all points of the front. He knew he would only have this chance to defeat the Potomac Army before it reached the James. As soon as there was a siege afterwards, the defeat of the Confederation was only a matter of time. Lee's losses in repelling the attack amounted to approximately 1,500 soldiers.

After the attack

On June 5, Grant asked Lee to agree to the rescue of the wounded and dead on both sides. Lee insisted on a ceasefire request because the Confederates had no wounded in front of their lines - Lee had no objection to local white flag salvages. It was only when Grant admitted defeat and asked for a ceasefire that Lee agreed to the rescue on June 6th. When the ceasefire came into force on the evening of June 7th, almost all the dead remained to be salvaged.

From June 4th to June 12th the armies faced each other. Due to constant mortar raids , raiding troops , sniper operations and night attacks, the number of casualties almost doubled on both sides.

On June 6, Grant ordered a second line of trenches to be dug to cover up the withdrawal of the Potomac Army to the James.

On June 7th, Lee sent a brigade from Cold Harbor to the Shenandoah Valley to evict Union forces from the southern valley. The next day he sent his cavalry after Sheridan, who he feared should reinforce the Union forces in the southern Shenandoah Valley. On June 12, he ordered Lieutenant General Early with his II Corps to take the Shenandoah Valley, cross the Potomac and threaten Washington .

In the meantime, the James Army's attack on Petersburg on June 8th had failed. On the night of June 13th, Grant began withdrawing the XVIII. and IX. Corps. Under the protection of his returning cavalry, he built a 2,200 m long pontoon bridge over the James, over which his corps reached the south bank on June 13 and 14. The Confederates had noticed Grant's withdrawal, only for an entire day Lee had no idea what Grant was up to.

The subsequent movements of both armies ended the overland campaign and led to the siege of Petersburg.

Special duties of the armies

enlightenment

The main burden of the reconnaissance still lay with the cavalry. As long as the armies were not yet buried, the reconnaissance was often an armed reconnaissance, which also had the task of acting as an advance division to reach important parts of the terrain in front of the enemy and to hold them until the main forces arrived. The Union cavalry was particularly suitable for this, as it was equipped with the superior Sharps carbine . This shows the occupation of the Cold Harbor intersection on May 31st. As soon as the armies were buried, raiding parties were increasingly used to determine the strength of the enemy. This freed the cavalry to raid supply depots and lines. During the battle, balloons were also used for reconnaissance purposes, by observing them the course of the field fortifications and reinforcements brought in from the hinterland could be recognized at an early stage.

connection

Because of the short distances within the corps of the armies, telegraphy was of little importance. The connections were kept by couriers, since almost all orders and messages were given or were drafted in writing. These were officers who brought the written orders during the battle with the verbal explanations of the commanding officer and were often able to exert considerable influence on the recipient of the order. Only particularly capable and reliable officers were used for this purpose.

care

In contrast to the Atlanta campaign , the railroad played a subordinate role in supplying the armies during the battle, as the supply bases were very close to the positions for the Potomac Army at Pamunkey - accessible by water - and for Northern Virginia -Army in Richmond, the terminus and crossing point of many southern railways. From these supply bases, supplies were brought to the divisions in wagons and ox carts pulled by mules.

medical corps

The medical service during the battle was no different from that of the entire civil war. The doctor's most important aid was the saw, limb amputations were the rule, the soldiers were usually anesthetized with chloroform and ether . The general shortage of these narcotics in both armies, especially in the Northern Virginia Army, meant that soldiers were made less sensitive to pain with whiskey or even had to bite a bullet. Although the art of amputation was valued very highly, many soldiers died during convalescence because of the indescribably poor sanitary conditions of epidemics and secondary diseases such as pneumonia or gangrene. A famous example of this was Lieutenant General Jackson in 1863 .

Immediate impact and importance

After the Battle of Cold Harbor, the Union War Department was unable to send Grant replacements for the fallen soldiers. That would only be possible when the next class was called up. The great blood toll of the battle strengthened the opponents of the war in the Union and gave the Democrats a boost in the upcoming election campaign.

For General Lee, the end of the overland campaign and the Battle of Cold Harbor, despite the tactical victory achieved, meant the end of the Northern Virginia Army's strategic offensive capabilities, which led to the surrender at Appomattox Court House after a nine-month siege of Petersburg by the Union armies .

Grant's leadership skills during the campaign and especially the battle later became controversial. Critics called him the "butcher", for others he was the glorious winner. The spokesman for the critics was Brevet Major General Martin T. McMahon. He claimed to speak for the majority of the participants in the battle. He accused Grant that the battle should never have been fought and that there was no military need for it. And it joins the previous, bloody and unnecessary battles of the overland campaign. This point of view must be seen from the perspective of the upcoming presidential elections. McMahon was a supporter of McClellan, President Lincoln's Democratic rival candidate. In the same allegation, McMahon claimed that if General McClellan had received the same support from Washington two years earlier as Grant later, the war would have been ended by McClellan by then.

More reluctant critics included Potomac Army Commander-in-Chief, Maj. General Meade, who wrote in a letter to his wife on June 5:

"I think Grant has had his eyes opened, and is willing to admit now Virginia and Lee's army is not Tennessee and Bragg's army."

"I think Grant's eyes have now been opened and he's ready to accept that Virginia and Lee's armies are not comparable to Tennessee and Bragg's armies."

Grant's decision to launch the frontal attack was based on self-delusion. He was convinced that the soldiers of the Northern Virginia Army were already defeated by the constant attacks during the campaign and that it would only take one last determined effort to defeat them once and for all, and that his soldiers had a better morale. In addition there was the success of the frontal attacks at Spotsylvania. He overestimated Lee's losses and underestimated that the Northern Virginia Army still consisted of many battle-hardened veterans while the Potomac Army had made up its losses with nearly 40,000 inexperienced soldiers. Meade gave the second attack order, which was not carried out, because the first attack had almost reached the goal of breaking into the Confederate positions and it was now a matter of vigorously pursuing it, and because the losses reported to him were not so significant that the attack would have been stopped have to.

Despite this tactical victory, Lee, one of the last in the Northern Virginia Army, did not change the predicament of the Confederation, which was on the strategic defensive. In particular, the short-term hope of influencing the outcome of the presidential campaign in their favor was dashed by the Union's successful Atlanta campaign. Grant had achieved the goal of the overland campaign and the Union remained on the strategic offensive despite the defeat.

The importance of the Battle of Cold Harbor beyond that is also controversial. The battle is considered to be the first modern battle and thus defined as the end of Napoleonic warfare .

The Battle of Cold Harbor showed a new dimension to the war. There were frontal attacks against field fortifications, mortar attacks, raiding troops and night attacks before, but never at such a simultaneity. The weapons technology had not changed compared to Gettysburg. What subjectively increased the weapon effect so extremely for the individual soldier was the concentration of fire as many different weapons as possible in a certain space and at a certain time. This was made possible in particular by the zigzag shape of the field fortifications. The battle was the end of the block and row approach to attack.

It was further concluded that the attack by infantry against infantry in field fortifications must be unsuccessful and would only require great sacrifices, especially in view of the ever increasing efficiency of the weapons. A way out of this strategic military situation was not found and in the First World War obviously led to the war of attrition.

The Napoleonic warfare was not over. The wars of German unification were waged under this auspices, the western campaign and the battle for East Prussia during the First World War are examples of such wars. It was only when the war of movement froze and the generals couldn't think of anything better to resort to tactics that had already been tried out in Cold Harbor regardless of the losses.

The Battle of Cold Harbor showed was how the war of the future look like, and looked ahead to the trench warfare of the First World War.

literature

- United States War Dept .: The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Govt. Print. Off., Washington 1880-1901.

- Dierk Walter: In no man's land. Cold Harbor, May 31 to June 3, 1864. In: Stig Förster et al. a. (Ed.): Battles of world history. 2004, pp. 200-215, ISBN 3-423-34083-5 .

- Gordon C. Rhea: Cold Harbor: Grant and Lee, May 26-June 3, 1864. Baton Rouge Louisiana State University Press, 2002, ISBN 0-8071-2803-1 .

- James M. McPherson (Ed.): The Atlas of the Civil War. Philadelphia 2005, ISBN 0-7624-2356-0 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e Battle Detail Cold Harbor. US Department of the Interior - National Park Service, August 17, 2016, accessed July 30, 2020 (English, brief description of the battle).

- ↑ a b James M. McPherson: Battle Cry of Freedom . 1st edition. Oxford University Press, New York 1988, ISBN 0-19-516895-X , pp. 733 .

- ^ Union losses. Cornell University Library, 2020, accessed July 8, 2020 (Official Records, Vol. 36, Part 1, p. 188).

- ↑ The War of the Rebellion. Series I, Volume XXXIII, p. 827 f .: Primary goal of the campaign

- ↑ Terry Conners: Battle History : Hold at Any Price ( February 4, 2012 memento in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ General Horace Porter: Campaigning with Grant. P. 174: Sew in Grant's name badges

- ↑ General Horace Porter: Campaigning with Grant. P. 176 f .: Further attacks only if there is a prospect of success

- ^ Greg Goebel: The American Civil War. S. [71.2]: [1]

- ↑ General Horace Porter: Campaigning with Grant. P. 179: Grant's Regret for the Attack

- ↑ The War of the Rebellion. Series I, Volume XXXVI, Part III, pp. 600, 638 f., 666 f .: Exchange of notes Grant - Lee

- ↑ James McPherson: Battle Cry of Freedom . P. 487

- ↑ The Life and Letters of George Gordon Meade: Meade's letter to his wife

- ^ Paddy Griffith: Battle Tactics of the Civil War. Yale University Press, New Haven 1989, ISBN 0-300-04247-7 - The theses in this book are controversial.

Web links

- Cold Harbor. National Park Service, October 3, 2007, accessed April 1, 2016 (Battle description).

- Grant-Lee Correspondence on Burying the War Dead. VCDH - University of Virginia, 2002, accessed on December 4, 2010 (English, exchange of notes Grant - Lee on the rescue of the wounded (summary from the Official Records)).

- It Seemed Almost Like Murder To Fire On You. Greg Goebel, September 1, 2009, accessed December 4, 2010 (Reports on the Civil War).

- North Anna and Cold Harbor. civilwarhome.com, February 20, 2002, accessed December 4, 2010 (English, detailed description of the battle).

- Cold Harbor. Ohio State University, 2010, accessed December 4, 2010 (illustration by Major General Martin T. McMahons).

- "Nobody could stand upright and survive for a second"