Somnium scipionis

The Somnium Scipionis ( Latin 'Scipio's dream') is a story from the sixth book of Cicero 's De re publica (written from 54 to 52 BC), which she forms, largely separately passed down in a commentary by Macrobius . Its content is based on the year 129 BC. Fictional story of Scipio Aemilianus to be used . He told eight listeners about a dream that he had twenty years earlier while visiting King Masinissa of Numidia . His adoptive grandfather Scipio Africanus and his biological father Paullus appear, rapture him from the earth and show him a cosmological scenario that only men who have taken on political responsibility are allowed to see and experience after their death as a reward for their deeds. Cicero receives Plato, who in the 10th book of the Politeia Socrates tells the "myth of He".

construction

| Chapter in 'De re publica' | Chapter in isolated edition | content |

|---|---|---|

| 6.9-10 | 1.1-4 | Framework: Reception by Masinissa; Dream apparition of Scipio Africanus maior. |

| 6.11-12 | 2.1-3 | Scipio Africanus maior predicts the future for the adoptive grandson Scipio Africanus minor. |

| 6.13 | 3.1 | He proclaims eternal bliss as a reward for deserving statesmen. |

| 6.14 | 3.2 | Scipio Africanus maior makes Scipio's biological father Aemilianus appear. |

| 6.15-16 | 3.3-4 | Aemilianus forbids Scipio to want to die immediately out of longing for this bliss and urges him to lead a virtuous life. |

| 6.17-19 | 3.5-5.3 | Africanus maior again: vision of the celestial spheres and the music of the spheres from the Milky Way . |

| 6.20-22 | 6th | Division of the earth; the habitable zone of the earth locally limits earthly glory. |

| 6.23-25 | 7th | The great year and the cyclical return limit earthly fame in time. |

| 6.26-29 | 8-9 | The human soul is immortal and after separation from the body, if it deserves it, it reaches heaven. |

content

| chapter | Table of contents |

|---|---|

| 6.9-10 | Scipio Africanus Minor arrives in Africa to take the position of a military tribune with the consul Manius Manlius. He visits King Masinissa, with whom he is extremely friendly for a whole day and then deep into the night. When Scipio goes to sleep, his dream begins: his grandfather, Africanus maior, appears to him and asks him to look down on the earth. |

| 6.11-12 | Africanus maior predicts his future: Scipio minor will destroy Carthage as consul, will visit Egypt, Syria, Greece and Asia as ambassador and will be elected consul for the second time. He will destroy Numantia and end the war in Spain. His cousin Tiberius Gracchus will, however, seek his life. |

| 6.13-14 | A safe place in heaven is prepared for all who have saved and supported the fatherland. Africanus Minor asks if his father Paullus and Africanus Maior live themselves. With tears, Scipio sees his father approaching. |

| 6.15-16 | However, Scipio is only allowed to pass away after he has completed his task. The grandfather advises him to always be fair. The Roman Empire is only a tiny point in the cosmos. |

| 6.17-18 | Africanus Maior explains to him that seven planets move in a circular orbit around the earth. The various circular paths generate tones that combine to form harmonies. The outermost planets produce the highest notes and the innermost the deepest. |

| 6.19-20 | The human ear has become numb to these sounds, which would overwhelm it anyway. Scipio looks at the earth. Africanus shows him how small it is and that only individual places are inhabited by people. |

| 6.21-23 | He also explains to him that the earth is divided into different climate zones. Fame is local. It is impossible to have fame forever. |

| 6.24-26 | After a Platonic year , when all heavenly bodies have reached exactly the same position again, he will be forgotten. Earthly fame is therefore of little value, it dies with the individual. Scipio Minor is impressed and promises to follow the advice. |

| 6.27-29 | Only what always moves by itself is eternal. When the movement ends, life is inevitably over as well. Everything that has to be driven from outside is inanimate. But those who lived wickedly will only return to their place in heaven after they have hovered around the earth for centuries.

The grandfather disappears; Scipio wakes up. |

cosmology

In the dream Scipio is transferred to his grandfather Scipio Africanus, who, according to the teachings of the Pythagoreans, stays on the Milky Way as the residence of the souls released from their physicality, and overlooks the entire cosmos from above. The spherical earth rests in the center and is surrounded by seven planetary spheres and the sphere of the fixed stars , on which Scipio himself is now. The whole sky circles from east to west, the sphere of the fixed stars the fastest, while the spherical spheres below have their own movement in the opposite direction and therefore rotate (slightly) more slowly from east to west. The moon has the strongest proper motion , followed by Mercury , Venus , Sun , Mars , Jupiter and Saturn .

The speeds of the rotating spheres depend on the spaces between them. According to the Pythagorean doctrine, the circling of the eight spheres produces certain tones that can no longer be heard by people who have already got used to it in the womb. However, each sphere produces a sound, the pitch increasing with distance from the earth. There are seven different tones due to the pitch, because the outermost sphere of the moon and the fixed stars together form an octave. The difference between the lunar and Mercury spheres is half a tone, that between Venus and the sun one and a half tones, between the sun and Mars, Mars and Jupiter, Jupiter and Saturn half a tone and finally between Saturn and the firmament another one and a half tone. Scipio is looking at a cosmos whose harmonious construction - the so-called music of the spheres - is musically perceptible.

geography

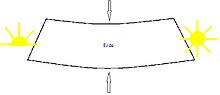

Cicero has Scipio Africanus maior sketch an earth on which the emerging Roman Empire is only a small patch. Between these individual inhabited "spots" lie vast wastelands, and the people are sometimes so far apart that they are already living in the next "hemisphere" (north, south, west, east) and thus they are opposing residents, secondary residents and antipodes .

Cultures are not only limited by the seas, but also by the climatic zones : there are two poles, both of which are surrounded by the most distant belts. All these parts are frozen in frost. The middle belt is the largest and withered in the glow of the sun. There are only two habitable belts. The southern one is unknown to the northern one, and viewed from the north, people stand on their heads. Because the earth narrows at the poles and becomes wider at the sides. Overall, it represents a small island around which the ocean flows.

Reception in ancient times

Cicero's work de re publica was evidently received widely in antiquity.

Virgil's Aeneid (Visit to the Underworld)

The sixth book of the Aeneid contains Anchises' prophecy to Aeneas and is considered the climax of the story. The whole thing takes place in the underworld. Virgil commentator Maurus Servius Honoratius (4th century AD) claims that Aeneas dreamed of the underworld and was not actually there. Cicero also tells of a dream, but in contrast to Virgil's Aeneid it takes place on heights.

Macrobius' commentary

helped the final part of the soon-to-be-lost work de re publica Macrobius to survive beyond antiquity with a commentary that was many times longer than the commented passage, namely two books that Macrobius divided. In the tradition of the Neoplatonic school, Macrobius saw this commentary as a substitute teacher who was supposed to explain the philosophically demanding text to his pupils; so the two books are addressed to Macrobius son Eustathius. Macrobius does not comment on all passages of the original (he quotes around 60% of them and leaves the framework story uncommented in particular), but he treats the cited in the order given in the original.

| Chapter in 'De re publica', book 6 | Topic with Macrobius and chapter specification |

|---|---|

| Introduction: Somnium Scipionis and Plato myth about the Er (1.1–5.1) | |

| 5.2 | Meaning of the numbers 7 and 8 (1.5.3–6.83) |

| 8.12 | The virtues and the abode of the soul (1.8.1–9) |

| 10.1-8 | The body as the prison of the soul and its descent into the body (1.10.9-12) |

| 13.1-4 | The prohibition of suicide (1.13.5-20) |

| 14.1 | The essence of the soul (1.14.1-20) |

| 16.1-2, 17.1-5 | Position and orbits of the stars (1.14.21–22.13) |

| 18th | Music of the Spheres (2.1–4) |

| 20th | Structure of the earth (2.5–9) |

| 23 | Outline of time (2.10) |

| 24 | The great year after which all the stars are in the same position again (2.11) |

| 26th | Immortality of the soul (also with the inclusion of Plato and Plotinus) (2.12) |

| 27 | The soul as a moving force (2.13–16) |

| 29 | Conclusion (2.17) |

Macrobius not only quotes Cicero, but also Plato (428 / 427-348 / 347 BC) and Plotinus (205-270 AD) as well as Porphyrios (234 to the early 4th century AD). His work was quoted a lot up to the 10th century, so it was probably widely read and then rediscovered by Petrarch. Maps of the earth were also attached to the work, one of which Columbus even studied.

Reception and appreciation in modern times

- The Italian humanist Francesco Petrarca wrote a commentary on the Somnium Scipionis .

- Johannes Kepler's Somnium , published posthumously in 1634, has strong references to Cicero's work. In it, the first-person narrator dreams of a book in which a ghost tells the protagonist of scripture and his mother about the moon and in doing so unfolds the lunar inhabitants' perspective of space and earth. Kepler bases the presentation on his own astronomical knowledge as well as that of Galileo and Copernicus.

- In 1772, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart composed Il sogno di Scipione , an opera inspired by Somnium Scipionis .

- Richard Harder describes Cicero's Somnium Scipionis as a top philosophical achievement that has influenced many other works up to the present day.

Work editions

- see De re publica

Audio book:

- Somnium Scipionis a Cicerone scriptum, read by Nikolaus Groß, published by LEO LATINUS, without a year. ISBN 978-3-938905-17-3

literature

- Mireille Armisen-Marchetti: Macrobe. Commentaire au Songe de Scipion. Volume 1. Les belles Lettres, Paris 2001, ISBN 2-251-01420-3 , pp. XXIV – XXXVI.

- Karl Büchner : Somnium Scipionis. Source - shape - meaning. Karl Steiner Verlag, Wiesbaden 1976, ISBN 3-515-02306-2 (Hermes. Journal for Classical Philology, individual publications, issue 36).

- Richard Harder : About Ciceros Somnium Scipionis. In: Writings of the Königsberger Gelehrten Gesellschaft, Geisteswissenschaftliche Klasse , 6th year, 1929, Issue 3. Niemeyer, Halle 1929. Reprinted in: ders .: Kleine Schriften , edited by Walter Marg. Beck, Munich 1960, pp. 354–395.

- Karlheinz Töchterle : Cicero's Staatsschrift in the classroom: a historical and systematic analysis of its treatment in the schools of Austria and Germany 1978, page 55 ff.

Web links

- Website of the TU Berlin: German and Latin text each as a unit

- Private website: Latin and German text translated in sections, with numerous content references

- Latin Library: Latin text

- Ancient History: English translation with commentary

- Edition Alpha et Omega: German text based on the translation by GH Moser, Stuttgart (1828)

Individual evidence

- ↑ The conversation itself is historical: The senator and historian Publius Rutilius Rufus , who took part, lived since 92 BC. Banished in Smyrna and was 78 BC. Visited there by Cicero. Cic. de re publica 1,8: [...] disputatio repetenda memoria est, quae mihi tibique quondam adulescentulo est a P. Rutilio Rufo, Zmyrnae cum simul essemus compluris dies, exposita [...] ; "[...] I have to remember a conversation that was told to me and you [meaning Cicero's brother Quintus] as a young man by Publius Rutilius Rufus, when we were in Smyrna for several days [...]"

- ↑ partly after Mireille Armisen-Marchetti: Macrobe. Commentaire au Songe de Scipion. Volume 1. Paris, Les belles Lettres, 2001. pp. XXVIIf.

- ↑ In various fragments of Pythagorean writings, however, there are different information about the tone intervals between the spheres.

- ↑ Ad Atticum 5.12.2 and (Caelius) ad Familiares 8.1.4, also the counter-writing of Didymus peri tes Kikeronis politeias ( Carl Hosius ; History of Roman Literature up to the Legislative Work of Emperor Justinian , Part 1. Munich, 4th edition 1966 . 496)

- ↑ Georgius Thilo , Hermannus Hagen (ed.): Servii Grammatici qui feruntur in Vergilii carmina commentarii . Leipzig 1884. 122f. This declaration is rejected in modern discussion except by L. Highbarger: The Gates of Dreams. Baltimore 1940

- ↑ Mireille Armisen-Marchetti: Macrobe. Commentaire au Songe de Scipion. Volume 1. Paris, Les belles Lettres, 2001. pp. XIXf.

- ↑ or Eustachius: Mireille Armisen-Marchetti: Macrobe. Commentaire au Songe de Scipion. Volume 1. Paris, Les belles Lettres, 2001. pp. XIV-XVI.

- ↑ Mireille Armisen-Marchetti: Macrobe. Commentaire au Songe de Scipion. Volume 1. Paris, Les belles Lettres, 2001. S. XXXIV.

- ↑ Mireille Armisen-Marchetti: Macrobe. Commentaire au Songe de Scipion. Volume 1. Paris, Les belles Lettres, 2001. S. LXVI-LXXI.

- ^ A. Hüttig: Macrobius in the Middle Ages. A contribution to the history of the reception of the Commentarii in Somnium Scipionis. Frankfurt / M., Bern ,. New York Paris 1990, p. 170; Images in the English language Wikipedia sv Macrobius

- ↑ Richard Harder: About Ciceros Somnium Scipionis . Halle (Saale) 1929