Sudeten German Freikorps

The Sudeten German Free Corps ( SFK ), also Henlein Free Corps or Sudeten German Legion was one of Sudeten educated men paramilitary unit during the Nazi era under the command of Konrad Henlein , the leader of the Sudeten German Party (Sudeten). Adolf Hitler ordered the formation of the Freikorps on September 17, 1938 - at the height of the Sudeten crisis . The general command was located in Fantaisie Palace near Bayreuth .

Starting on September 19, 1938, members of the SFK carried out armed attacks on Czechoslovak institutions in the Sudetenland , starting from the German Reich , in order to destabilize Czechoslovakia . Officially, the SFK was supposed to protect the Sudeten Germans from alleged Czech attacks. The SFK consisted of up to 40,000 " irregulars ". As a result of the Munich Agreement , the Sudetenland was annexed to the German Reich on October 1, 1938 . The existence of the SFK was thus irrelevant. The SFK was formally dissolved on October 9, 1938, and many of the Freikorps members were taken over into the SS .

In total, SFK troops carried out more than 200 terrorist actions, killing over 100 people and kidnapping around 2000 victims into the German Reich. The "irregulars" destroyed numerous state facilities in Czechoslovakia by blowing up or setting fire to them and captured weapons, ammunition and vehicles. More than 50 of the Freikorps fighters were killed in the SFK's terrorist actions. Most of the members of the SFK were poorly equipped and poorly trained due to the hasty setup. Sometimes they acted in an undisciplined manner. The often uncoordinated terrorist actions of the SFK had little military value, but high political value. They served Hitler's plan to destabilize and eventually destroy Czechoslovakia.

prehistory

After the First World War , almost three million Sudeten Germans lived in the newly formed multiethnic state of Czechoslovakia. Overall, the German-speaking population made up almost a quarter of the total population of Czechoslovakia. Since the founding of the Czechoslovak state, there have been currents and organizations, especially in the Sudetenland, that demanded autonomy or the connection of the Sudeten German territories to the German Reich or Austria . At the political level, these were the German National Party (DNP) and the German National Socialist Workers' Party (DNSAP). These parties, increasingly influential in the Sudetenland, were officially banned on October 4, 1933. The DNSAP had already dissolved on October 3, 1933 due to the impending ban on political parties. The background to these party bans was the charge of subversive activity.

The Sudeten German Home Front (SHF) was founded on October 1, 1933 as a new rallying movement for advocates of autonomy among the Sudeten Germans, and renamed the Sudeten German Party (SdP) on May 2, 1935. In the parliamentary elections on May 19, 1935, the SdP was the strongest party in the parliament of Czechoslovakia with 44 out of 300 seats and was able to win more than two thirds of the Sudeten German votes. From the start , the party chairman was Konrad Henlein , who later became the leader of the SFK. As chairman of the Sudeten German Gymnastics Association, Henlein shaped the development of this organization into a nationally-oriented association from the beginning of the 1930s. Henlein, as an integrating figure of the German-nationally-minded Sudeten Germans, seemed ideal for building a new political gathering movement. Until the beginning of 1938, however, the policy of the SdP with regard to autonomy or annexation of the Sudeten areas was not clear.

The increasing radicalization and turning of many Sudeten Germans to the SdP was based on a great disappointment with the situation in the Sudetenland. Even after the establishment of Czechoslovakia, there were Sudeten German demonstrations for the autonomy of the Sudeten territories, which were forcibly disbanded by the Czech security forces. In the 1920s, as a result of the Czech policy of assimilation, the proportion of Czech civil servants in relation to the proportion of the Czech population in the Sudetenland rose sharply. The reason for this was the language law passed in 1926, which required state employees to master the Czech language within six months. Those civil servants who failed to do so were dismissed. Overall, the proportion of the Czech population in the Sudetenland also increased steadily. In addition, the global economic crisis of 1929 had a particularly strong impact on the Sudeten German areas. The proportion of unemployed in the Sudeten German population was twice as high as in the Czech population.

Soon after the " annexation of Austria " to the German Reich on March 12, 1938, the bourgeois parties in Czechoslovakia, the German Christian Social People's Party and the Federation of Farmers themselves, dissolved. Most of its members then joined the SdP. From this point on, only the Sudeten German Social Democrats and the Communists were essentially in opposition to the SdP.

At Hitler's invitation, Henlein and his deputy Karl Hermann Frank met with the Reich Chancellor on March 28, 1938 . As a common target it was agreed to demand the autonomy of the Sudeten areas and reparations for economic losses from Czechoslovakia. In the negotiations with Czechoslovak government representatives, the SdP should make unacceptable demands. These demands were announced to party functionaries on April 24, 1938 by the Karlovy Vary program at the party congress of the SdP.

On May 30, 1938, Hitler updated his plan to militarily destroy Czechoslovakia under the code name Grün . This arrangement was to be flanked by a propaganda war . The measures defined were to support national minorities in Czechoslovakia, to exert influence on neutral states in line with German Sudeten policy and to wear down Czechoslovakia's resilience.

As the “ fifth column ” of the German Reich, the SdP subordinated itself more and more to the requirements of the Green case from the spring of 1938 , and thus contributed significantly to the worsening of the Sudeten crisis. For example, the Voluntary German Protection Service (FS) was formed in the Sudetenland in May 1938 , which had emerged from the security service of the SdP. The members of this militia-like organization, which was structurally based on the Sturmabteilung (SA) in the German Reich, were mainly active as auxiliary police officers. Members of the FS were sometimes also trained conspiratorially to carry out acts of sabotage and terrorism against Czechoslovak institutions.

The hope of the Czechoslovak government under President Edvard Beneš for Allied support was not fulfilled. From the summer of 1938, the governments of Great Britain and France became increasingly involved in the Sudeten crisis at the diplomatic level. In addition, under Lord Runciman , a delegation was sent to Czechoslovakia on August 3, 1938 , to gain an overall picture of the crisis situation during a stay of several weeks. In the end, several bilateral consultations between France and Great Britain did not result in an assurance of military support. Contrary to what was expected, France and Great Britain showed a certain understanding of the Sudeten German demands. The British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain met Hitler twice in the German Reich in September 1938 to prevent the threatening war. At these meetings, however, Hitler insisted on the cession of Czechoslovakia and, if these demands were not met, announced a war.

Worsening of the Sudeten Crisis (September 10-15)

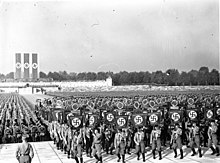

At the beginning of September 1938 the Sudeten crisis came to a head. At the Nuremberg Rally of the Nazi Party (NSDAP), of from 5 to 12 September in Nuremberg took place, the leadership of the Sudeten participated. On September 12, Hitler said in his closing speech: “The Germans in Czechoslovakia are neither defenseless, nor are they abandoned. One should take note of that. ”On September 10, SdP functionaries who remained in the Sudetenland had received instructions from the deputy chairman of the SdP Karl Hermann Frank to organize violent clashes between Sudeten German demonstrators and Czechoslovak law enforcement officers. From September 10th, there were violent actions of the FS in many Sudeten German cities in the protection of stimulating anti-Czech rallies. Thousands of Sudeten German demonstrators had vehemently demanded the autonomy of their homeland. Hitler's closing speech at the Nazi Party Congress on September 12th was broadcast on German radio and could also be received in the Sudetenland. The situation then escalated.

Armed members of the FS carried out acts of terrorism and sabotage against Czechoslovak institutions such as police stations, customs offices and barracks. The aim of these mostly uncoordinated actions was the forcible appropriation of weapons, the seizure of power in the Sudetenland and the overall destabilization of the Czechoslovak state. In West Bohemia , which was particularly hard hit , the Czechoslovak government then proclaimed martial law on September 13 . Czechoslovak security forces finally took action against the partly armed insurgents. However, the staged popular uprising was not fully supported by the Sudeten German population. In addition, Sudeten German anti-fascists , mainly social democrats and communists, entered into the clashes with the FS members. In particular, the paramilitary Republican Defense , consisting of Sudeten German Social Democrats, resisted the attacks by the FS.

By September 17, the mass demonstrations subsided. However, the FS continued to sabotage Czechoslovak institutions. A total of 27 people died in the clashes, including eleven Sudeten Germans. The SdP leadership had planned this in order to increase the pressure on the government of Czechoslovakia. From then on, thousands of Czechs, Jews and Sudeten German anti-fascists from the Sudetenland fled to Central Bohemia for fear of attacks.

On September 13, the leadership of the SdP returned to the Sudetenland. Due to the chaotic conditions there, the SdP leadership was no longer able to work in an organized manner. On the evening of September 13th, Frank issued an ultimatum to the Czechoslovak government, in which the withdrawal of the Czechoslovak security forces from the crisis area and the return of police power to the Sudeten German mayor was demanded. Since the ultimatum did not have the desired effect, the party headquarters of the SdP in Prague was disbanded on September 14, and negotiations with the Czechoslovak government were suspended. The leadership of the SdP finally moved to the German Reich via Asch . On September 15, Henlein broadcast the slogan “ We want to go home to the Reich! " out. In this radio address he called for the dissolution of the Czechoslovak state, referring to the alleged "irreconcilable will to annihilate" the Czechs against the Sudeten Germans. As a result, the FS was banned in Czechoslovakia on September 15, and the SdP a day later.

Thousands of Sudeten Germans, especially members of the FS and SdP functionaries, fled across the border into the German Reich from mid-September. The reasons lay partly in the standing rights imposed and in the summoning of Sudeten Germans to the Czechoslovak army . The refugees were housed in assembly camps near the border with Czechoslovakia and looked after by SA and the National Socialist People's Welfare (NSV).

Formation of the SFK (September 16-18, 1938)

On September 16, 1938, the deputy chairman of the SdP, Karl Hermann Frank, successfully asked Adolf Hitler for permission to set up a Sudeten German Freikorps. On the morning of September 17, Hitler ordered the formation of the SFK under the direction of Konrad Henlein. Frank became deputy commander of the Freikorps under Henlein. On the same day, the High Command of the Wehrmacht (OKW) and the High Command of the Army (OKH) were informed of the establishment of the SFK by telex. Lieutenant Colonel Friedrich Köchling was then appointed liaison officer of the OKW to the SFK as its military advisor. On the evening of September 17, Köchling was given far-reaching powers after a personal interview with Hitler. However , Köchling was unable to enforce the requirements of his superiors to submit the Sudeten Germans capable of military service to the Wehrmacht . Immediately after the decision to form the SFK, Henlein turned to the Sudeten Germans on the German radio on September 17, calling on the smashing of Czechoslovakia and the Sudeten Germans to argue. The Sudeten German Freikorps was also called Freikorps Henlein or Sudeten German Legion after its leader .

Konrad Henlein

(1898–1945)

Commander of the SFKKarl Hermann Frank

(1898–1946)

deputy commander of the SFKAnton Pfrogner

(1886–1961)

Chief of Staff at the SFKMax Jüttner

(1888–1963)

liaison officer of the SA to the SFKGottlob Berger

(1896–1975)

liaison officer of the SS to the SFK

On September 17th, the staff of the SFK moved into its headquarters in Donndorf Castle near Bayreuth . The public was left in the dark, as it was suggested by radio and the press that the top of the SdP politicians would operate from the Sudeten German Asch. Besides Koechling as a liaison officer of the OKW the staff of SFK yet liaison officers were the SA , SS and the National Socialist Motor Corps (NSKK) provides beige been for the direct exchange between the staff of the SFK and their respective leadership. In addition, the head of the OKW defense , Admiral Wilhelm Canaris , was in constant contact with Henlein.

Hitler personally announced the purpose of the SFK in a telex to the OKH on September 18: "Protection of the Sudeten Germans and maintenance of further unrest and clashes". The SFK should in consultation with the High Command conspiratorial care in small raiding parties from the German Reich from the Sudetenland by terrorism for permanent unrest. The members of the SFK were to be deployed in their home districts, where they had local knowledge, according to "compatriot points of view". Furthermore, Hitler gave the order to set up the SFK immediately in the German Reich and to equip it exclusively with Austrian weapons. In addition, Köchling later stated that the organizational structure of the SFK should be based on the structure of the SA. Only Sudeten German men of military age were allowed to be recruited for the SFK, entry of Reich Germans into the SFK was prohibited. Nevertheless, members of the SA and the NSKK were also Reich Germans in the SFK, as they were needed for leadership positions in the SFK commandos.

The "irregulars" remained citizens of Czechoslovakia in order to be able to legally enter the Sudetenland again. Many of them belonged to the FS or were previously reservists or conscripts in the Czechoslovak army before they fled .

On September 18, Henlein published the "Command of the Sudeten German Freikorps No. 1":

“Konrad Henlein ordered the Sudeten German Freikorps to be set up in order to give the Sudeten Germans capable of arms who had to flee across the border pursued by the Czech rulers the opportunity to fight for the freedom of our homeland. Entry into the Freikorps is voluntary. [...] The maximum age limit for the team is set at the age of 50 for weapons service. There is no age limit for officers and NCOs. Likewise, volunteers over 50 years of age can, at their own request, be used for relief services without weapons in the volunteer corps. Each of those reporting must provide two guarantors who stand up for his honorable disposition and manly demeanor. "

Establishment and structure of the SFK (September 18-20, 1938)

Candidates should report to the refugee accommodation to enter the SFK. The volunteers were assigned to the central assembly point of the SA via the lines of the refugee accommodation. After the volunteers were accepted into the Freikorps, they were sworn in on Adolf Hitler and, as Czechoslovak citizens, committed treason . The SA in the border area to the Sudetenland was to organize the equipment, food and accommodation of the "irregulars". With regard to clothing, the following was ordered:

"The clothing of the 'Sudeten German Freikorps' will consist of: 1. Black flat cap with a white protrusion with a swastika made of white metal, black-red-black cockade on the ribbon , 2. Gray skirt (blouse) in SA (SS) cut, black red-black mirror, 3. black booties and marching boots, 4. gray or brown shirt with black tie, 5. black belt with shoulder strap, pistol or cartridge pouch, 6. gray windbreaker, 7. swastika armband on the left upper arm (but is only out of action to wear)."

The volunteer corps was equipped with carbines , submachine guns , machine guns , hand grenades and larger-caliber pistols. Initially, the entire Freikorps had 7,780 carbines, 62 machine guns and 1,050 hand grenades. Almost half of the "irregulars" were not equipped with weapons due to the lack of weapons until the SFK was dissolved. Although the Freikorps was under Henlein's sole command, the Wehrmacht advised the SFK leadership on operational issues and regulated the arming of the Freikorps formations.

The financing of the SFK was largely guaranteed by the Wehrmacht, but also partly by the SS, the Volksdeutsche Mittelstelle and other NSDAP organizations .

From September 18, a group of SFK was set up along the German-Czech border in Silesia, Saxony, Bavaria and Austria, which were directly subordinate to Henlein's staff. At the end of September the groups in Silesia and Austria were split up again, so that later there were a total of six groups. Each group consisted of at least five battalions. Each battalion consisted of at least four companies , the companies in turn consisted of 150 to 300 men. Each company consisted of three to five platoons. Each platoon consisted of three to five flocks, each flock consisting of ten to fifteen men. The companies were in the near German border regions to the Sudetenland, the battalion headquarters in cities further away from the German-Czechoslovak border.

Each group had its own staff. In addition to the commanding officer, supported by an adjutant , the management staff of each group also included a chief of staff , an organizational leader, an orderly , a professional officer, an administrative officer and a chief doctor. There was also a Wehrmacht liaison officer in each of the group headquarters.

On September 18, there were between 10,000 and 15,000 men in the SFK. In the first days of the SFK's existence, thousands of volunteers registered for the SFK, so that on September 19, Henlein ordered that the SFK be limited to 40,000 people. According to a report by the SFK on September 22nd, this number was to be increased to 80,000 by order of Hitler. At that time, however, only about 26,000 people belonged to the SFK. Especially after September 23, the date of the general mobilization of the Czechoslovak Army, the SFK received considerable inflow again. On October 1, the SFK comprised 34,500 or, according to other information, 40,884 men.

| group | number | Rod | Strength | commitment | commander | image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silesia, then Hirschberg and Breslau | I, later V and VI | Wroclaw | 6,851 men in eleven battalions (as of September 27, 1938) | Ratibor to Zittau | Fritz Köllner (1904–1986) | |

| Saxony | II, later IV | Dresden | 13,264 men in 14 battalions with 71 companies (as of October 1, 1938), from September 25, 1938 sections Schirgiswalde , Freiberg and Eibenstock | Zittau to Asch | Franz May (1903-1969) | |

| Bavarian Ostmark | III | Bayreuth | 5,999 men in 7 battalions with 28 companies (as of September 27, 1938) | Asch to Bayerisch Eisenstein | Willi Brandner (1909–1944) | |

| Alpenland / Danube, then Vienna and Linz | IV, later I and II | Vienna | 7,798 men in 9 battalions with 41 companies (as of September 27, 1938) | Bayerisch Eisenstein to Poysdorf | Friedrich Bürger (1899–1972) |

From September 19, a Sudeten German Air Corps was also affiliated to the SFK, which was located in Alt-Lönnewitz. The workforce amounted to two pilots and 42 men on the ground. In addition, 28 pilots were still in preparatory measures.

Intelligence service of the SFK

The SFK also had an intelligence service based in Selb , which was headed by Richard Lammel . On the one hand, the SFK's intelligence service had the task of coordinating and evaluating acts of terrorism and sabotage by the SFK. On the other hand, the intelligence service of the SFK should cooperate with the intelligence services of the German Reich in order to incorporate its findings into the military planning in the event of a potential German attack on Czechoslovakia. Lammel's order on September 19 to set up the SFK's intelligence service read as follows:

"Purpose and task: 1. If possible, to get in touch with the organizational offices in the Č.SR yourself. 2. To collect the statements and reports of the refugees and messengers for control and processing to the authorities of the Reich and the press. Implementation: For this purpose, the following will be set up: a) Establishment of a 'central office' in Selb, b) One 'office' each in Hof, Waldsassen and Dresden, c) Further offices will still be set up. "

For each group of the SFK, by order of September 20, news points were set up by Henlein's command, which were to be managed by intelligence officers. The intelligence offices were responsible for monitoring and exploring the military and political situation in the Sudetenland and the Czech Republic and for passing on relevant information to the SFK's headquarters.

Activities of the SFK (September 19 to October 1, 1938)

Individual SFK troops infiltrated over the border into the Sudetenland on the night of September 19 and, among other things, carried out an attack on the financial guard in Asch. From September 19, all groups of the SFK were ready for action. From this point on , members of the SFK infiltrated the Sudetenland every night along the entire German-Czechoslovak border. As a rule, the SFK commandos consisted of only a few dozen men due to their inadequate armament; at some border sections, however, troops of up to 300 "rioters" were deployed. With increasing intensity they carried out arson attacks and assaults on police, border and customs stations as well as other state institutions. The SFK troops also shot at Czechoslovak border and police patrols. The Czechoslovak security forces were able to repel a few attacks, in some cases violent fighting resulted in deaths on both sides. The Czechoslovak security forces were supported in the fighting by Sudeten German anti-fascists. The Republican Defense in particular protected the Czech state border in the units of the SOS ( Stráž obrany státu - Guard for the Protection of the State).

The OKH rejected the massive nature of the uncoordinated SFK actions, as the “irregulars” did not adhere to mutual agreements and in some cases even hindered the deployment of the Wehrmacht on the German-Czechoslovak border. OKW and OKH then successfully intervened with Hitler, who on September 20 ordered a reduction in SFK actions. Only squads of a dozen men should now act against precisely defined goals. In addition, the activities of the SFK could no longer be kept secret and met with some international rejection. Nevertheless, France and Great Britain intervened with the Czechoslovak government in favor of the German Empire. On its own, the Czechoslovak government finally accepted the London recommendations on September 21, which provided for the cession of the Sudeten German territories to the German Reich without a referendum.

The Czechoslovak security forces and officials were taken by surprise by this new situation. In several Sudeten German cities and towns, members of the SdP and the FS regained control over state institutions and functions. The Czechoslovak military withdrew from areas that protruded into the German Reich to a strategically more favorable line of defense. With the support of the SFK, the FS succeeded in disarming the Czech police in the Ascher region on September 22nd. This process was then repeated in Eger and Franzensbad . There and elsewhere, captured police officers and arrested Czech and Sudeten German anti-fascists were brought to the German Reich.

Despite the acceptance of the London recommendations by the Czechoslovak government, the SFK continued its terrorist actions from September 21st. In particular in the cleared Ascher Zipfel and in Schluckenau , irregulars were able to get stuck continuously from September 22nd. By September 23, the SFK's terrorist actions in the Sudetenland increased. In Warnsdorf , for example, members of the SFK were able to steal 18 million crowns from the state bank and divert a train to the German Reich in Eisenstein .

Due to considerable protests in Czechoslovakia against the acceptance of the London Agreement, there was a change of government on September 22nd. The new Czechoslovak government ordered general mobilization on September 23 . By September 28th, 1,250,000 soldiers of the Czechoslovak army were in action. After the general mobilization was announced, thousands of Sudeten Germans evaded conscription after a radio call from Henlein and fled across the border into the German Reich on the night of September 24 with the support of the SFK. There they mostly joined the SFK and strengthened it considerably. The Czechoslovak military immediately moved into the Sudetenland. In some cases, the SFK commandos were consistently attacked immediately after crossing the border. However, the SFK was not up to a well-trained and heavily armed army due to its inadequate training and armament. As of September 24th, the SFK's strategy changed. Instead of carrying out acts of sabotage and terrorism, the SFK shifted the focus of its activities to armed reconnaissance companies on behalf of the Wehrmacht. However, to a lesser extent, the SFK continued its terrorist actions and raids until October 1st.

On September 25, the Czech army withdrew from the Jauernig district for strategic military reasons . Members of the SFK then occupied this area. They received support from SS-Totenkopfverband , which strengthened the SFK in the Ascher Zipfel on the same day. There, an advance by the Czechoslovak army was successfully repulsed on September 25th.

From September 24th, OKW was the sole authority in the border area to the Sudetenland. From September 28, border crossings had to be reported to the local border guard leader and planned activities had to be discussed with him. In addition, on September 30, the OKW ordered the SFK to be subordinate to the Wehrmacht after the German troops marched into the Sudetenland. Upon intervention by the SS, Hitler withdrew the OKW's orders on the evening of September 30th and placed the SFK under the command of Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler . The background for this change in command was the plan that SFK members should perform police duties in the Sudetenland.

On October 1, 1938, the Munich Agreement , which had been negotiated in the meantime, entered into force, which stipulated the annexation of the Sudeten German territories to the German Reich. This made the existence of the SFK irrelevant. Köchling later recorded 164 "successful" and 75 "unsuccessful" actions by the SFK. SFK associations killed 110 people, wounded 50 and abducted them to Germany in 2029. For example, 142 Czechoslovaks were interned in Altenfurt on October 17, including 56 police officers, 52 customs officers, 16 gendarmes and 18 military personnel.

The casualties of the SFK were 52 dead, 65 wounded and 19 missing. In addition to ammunition and vehicles, 341 rifles, 61 pistols and 24 machine guns were also captured. Many Czech facilities had been destroyed mainly by arson or demolition.

Dissolution of the SFK (October 1 to 9, 1938)

The Wehrmacht advanced into the Sudetenland in stages between October 1 and October 10 without a fight. In the wake of the Wehrmacht, SFK units also came to the Sudetenland, which were initially no longer assigned any significant functions. On October 2nd there was an exploratory discussion between the SFK Pfrogner's chief of staff and Police General Kurt Daluege about the further use of former “irregulars”, but this did not produce any noteworthy results. Arbitrary arrests, looting, confiscations and house searches were now forbidden to the members of the SFK on Henlein's orders. However, this instruction had to be repeated on October 4th, also due to domestic and foreign complaints, as there were arbitrary acts and pogrom-like riots on the part of the "irregulars" in many places in the Sudetenland . Political opponents as well as Jews, including both Czechs and Sudeten Germans, had been terrorized from October 1st by "irregulars", SdP supporters and members of the FS. Only the Wehrmacht was able to stop further excesses. In the wake of the Wehrmacht, the security police also came to the Sudetenland to arrest opponents of the Nazi regime in an organized manner. Around 2,000 Sudeten German anti-fascists , mainly Social Democrats and Communists, were arrested and sent to the Dachau concentration camp . As of December 3, 1938, the Czech Interior Ministry stated that a total of 151,997 Czechs, Jews and Sudeten German opponents of the Nazi regime fled the Sudetenland into the interior of Czechoslovakia.

The Wehrmacht finally stopped supporting the SFK. As a result, the SS was unable to adequately supply the members of the Freikorps. So the SFK gradually disintegrated in the first days of October and many “irregulars” settled in their hometowns. On October 9, 1938, the SFK was officially dissolved by Henlein's appeal. Former members of the SFK later received the medal in memory of October 1, 1938 .

After the formal end of the SFK, the debts and damage that had been caused by SFK members were still outstanding. The supply of the "irregulars" was done by local traders who, in the belief that they would later be compensated by the Wehrmacht's Imperial Services Act, made advance payments. Corresponding claims for damages could be made at the settlement center in Reichenberg . However, the outstanding debts were never paid.

Members of the SFK received compensation for physical damage. Those who suffered physical damage during their deployment between 20 and 30 September were entitled to compensation in accordance with the Wehrmacht Welfare and Supply Act. This regulation also applied to the surviving dependents of fallen “free rioters”.

Integration of former members of the SFK into the National Socialist power apparatus

Even when the SFK was in the process of being dissolved, the SS recruited high-ranking SFK members in particular for their organization. This led to clashes with the SA, which the SFK members also wanted to win over. Gottlob Berger later said that he should select suitable “irregulars” from the SFK for the SS or the SS disposable troops. Many of the former volunteer corps members joined the NSDAP, SA, SS and other National Socialist organizations after the Sudeten region was incorporated. Members of the leadership of the SFK were given high ranks after joining the SA and SS. After the Sudeten German elections to the National Socialist Reichstag on December 4, 1938, former leading members of the SFK became members of the Reichstag . Among them were Henlein, Frank, Pfrogner, Lammel, Köllner, Brandner, Bürger and May.

After the dissolution of the SFK, Henlein became an honorary group leader in the SS and in June 1943 achieved the rank of Obergruppenführer in this organization. From the end of October 1938 until the end of the war, Henlein was Reichskommissar and Gauleiter for the Sudetenland in Reichenberg . On May 10, 1945, Henlein committed suicide while an American prisoner of war.

Frank became a member of the SS in November 1938 as an SS Brigade Leader. In this organization he later achieved the rank of Obergruppenführer. At the end of October 1938 he became deputy Gauleiter for the Sudetenland under Henlein. He held this position until March 15, 1939. From mid-March 1939 until the summer of 1943 Frank was State Secretary to the Reich Protector of Bohemia and Moravia . He then moved to the Hitler cabinet as Minister of State with the rank of Reich Minister for Bohemia and Moravia until the end of the war . From April 1939 until the end of the war, Frank was also in personal union Higher SS and Police Leader (HSSPF) in Bohemia and Moravia. Frank eventually became the most influential Nazi functionary in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia . After the end of the war, Frank went into American captivity near Pilsen . From there he was extradited to Czechoslovakia, sentenced to death in Prague and hanged on May 22, 1946.

Lammel, former head of the SFK's intelligence service, was promoted to SS-Standartenführer at the end of January 1939. After the dissolution of the SFK, he became Gaustabsamtsleiter under Henlein.

The former SFK leader of the Bayrische Ostmark Brandner group became a member of the SS with the rank of Oberführer. In this function, he led SS-Section XXXVII (Reichenberg). In the SS he rose to SS-Brigadführer in 1943. Brandner later became the deputy of HSSPF Croatia Konstantin Kammerhofer and at the same time was deployed as police area leader in Croatia. Brandner died on December 29, 1944 as a result of being shot in the head after a partisan attack.

Three other commanders of the SFK became members of the SA. As an SA standard leader, Bürger built the SA Brigade North Moravia-Silesia. He also became an adjutant to Gauleiter Henlein. From 1939 Bürger was head of the district organization and from 1940 in the Sudetenland NSDAP district leader. Köllner achieved the rank of brigade leader in the SA, became head of the Gau organization and, from the end of March 1939, was Frank's successor under Henlein, Deputy Gau Leader of the Sudetenland. Köllner held this position until the beginning of March 1940. May was accepted as a group leader in the SA and commissioned with the establishment of the SA group Sudetenland.

Pfrogner, former chief of staff of the SFK, led the building staff of the Reich Labor Service (RAD) in the Sudetenland, where he achieved the rank of general labor leader .

Valuations and effects

The flight of high-ranking SdP functionaries to the German Reich after the failed attempt at insurrection in mid-September 1938 was no secret among the Sudeten Germans. The German propaganda, on the other hand, knowingly spread the false report that the SdP leadership would operate from the Sudeten German Asch. The resulting insecure supporters of the SdP felt abandoned by their leadership and the initially inactive Wehrmacht. In some places even the Sudeten German Social Democrats were able to regain influence. With the formation of the SFK, the leadership of the SdP intended to regain the confidence of the Sudeten German population. Hitler intended to destabilize Czechoslovakia through the unrest-causing activities of the SFK and to smash it as a state through the intervention of the Wehrmacht. The Grün case envisaged the Wehrmacht's invasion of Czechoslovakia in October 1938. In addition, Hitler hoped that the terrorist actions of the SFK would give him a better starting position for international negotiations. Because of this motivation, the SFK was created, with the SdP leadership subordinating itself to Hitler's guidelines.

The actions of the SFK were "primarily of a political-terrorist, not of a military nature". The motivation of many Sudeten Germans to join the SFK was, however, to protect Sudeten German interests. This attitude was already served by the name Sudeten German Freikorps, which was supposed to act as an independent force to defend Sudeten German interests. The terrorist actions of the SFK after the London Agreement, which laid down the cession of the Sudeten German territories to the German Reich, only served the goal of smashing the renamed Czecho-Slovakia as a state as a whole. After the London Agreement, the Munich Agreement was a further step towards this goal. With the annexation of the Czech Republic by the German Reich on March 15, 1939 and the independence of Slovakia , Green's instructions were implemented.

"The rather miserable end of the Freikorps, compared to the pathos of the call for Sudeten German self-defense at its beginning (September 17), symbolizes the degradation of Sudeten German interests and fates, as can be seen in the history of the Freikorps, into disruptive and unrest means of Hitler's crisis policy", so the conclusion of Martin Broszat . The Czech government in exile announced in a note dated February 28, 1944 that it had been at war with the German Reich since September 19, 1938. On September 19, the SFK's terrorist action began in the Sudetenland. They were also the outcome of Henlein's “Heim ins Reich” address of September 15, in which he stated that the Sudeten Germans could no longer live in one state with the Czechs. In another speech two days later, Henlein called for the smashing of Czechoslovakia and the entry of the Sudeten Germans into the SFK. The expulsion of Sudeten Germans from their homeland after the end of the Second World War was also a late consequence of terrorist activities. According to the "circular of the Ministry of the Interior of the Czechoslovak Republic of August 24, 1945 on the regulation of Czechoslovak citizenship according to the decree of August 2, 1945", former members of the SFK were also among those persons who were automatically deprived of their Czech citizenship. In addition to members of Nazi organizations and war criminals , former “free-rioters” had to answer before Czechoslovak special courts because they belonged to the SFK. In addition to imprisonment, the loss of civil rights and forced labor could be ordered. Death sentences were also passed in particularly serious cases . The SFK was also the subject of negotiations at the Nuremberg trial against the main war criminals .

Despite the now passable source situation, the SFK and its terrorist activities are partly unmentioned or downplayed in the "Historiography of the Sudeten German Landsmannschaft ".

literature

- Rudolf Absolon: The Wehrmacht in the Third Reich. Structure, structure, law, administration. Volume IV: February 8, 1938 to August 31, 1939. Oldenbourg, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-486-41739-8 .

- Zdeněk Beneš, Václav Kural (ed.): Understanding History - The Development of German - Czech Relations in the Bohemian Lands 1848–1948. gallery, Prague 2002, ISBN 80-86010-66-X (pdf; 4.2 MB) ( Memento from January 11, 2012 in the Internet Archive ).

- Detlef Brandes : The way to expulsion 1938-1945. Plans and decisions to “transfer” Germans from Czechoslovakia and Poland. Oldenbourg, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-486-56520-6 (2nd revised and expanded edition: Oldenbourg, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-486-56731-4 ).

- Martin Broszat : The Sudeten German Freikorps. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte . 9th year, issue 1, 1961, ISSN 0042-5702 , pp. 30-49 (PDF; 1 MB) .

- Ralf Gebel: “Heim ins Reich!” Konrad Henlein and the Reichsgau Sudetenland (1938–1945) (= publications of the Collegium Carolinum. Volume 83). Oldenbourg, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-486-56391-2 (2nd edition: Oldenbourg, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-486-56468-4 urn : nbn: de: bvb: 12-bsb00092896-5 ).

- Emil Hruška: Sudeten German Chapter - Study on the Origin and Development of the Sudeten German Union Movement ( Memento from May 9, 2009 in the Internet Archive ). In: German-Czech news. Dossier No. 2 , Munich 2003.

- Andreas Luh: The German Gymnastics Federation in the First Czechoslovak Republic. From national association to popular political movement (= publications of the Collegium Carolinum. Volume 62). Oldenbourg, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-486-54431-4 ( urn : nbn: de: bvb: 12-bsb00042083-2 ; 2nd edition: Oldenbourg, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-486-58135-X ).

- Jörg Osterloh: National Socialist Persecution of Jews in the Reichsgau Sudetenland 1938–1945. Oldenbourg, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-486-57980-0 ( urn : nbn: de: bvb: 12-bsb00092914-7 ).

- Werner Röhr : The "Green Case" and the Sudeten German Freikorps. In: Hans-Henning Hahn (Ed.): Hundred Years of Sudeten German History - A Völkisch Movement in Three States. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main et al. 2007, ISBN 978-3-631-55372-5 , pp. 241-256 (PDF; 134 kB) .

- Werner Röhr: September 1938: the Sudeten German Party and its Freikorps (= Bulletin for Research on Fascism and World War II. Supplement 7). Edition Organon, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-931034-06-1 .

- Heiner Timmermann u. a. (Ed.): The Benes Decrees. Post-war order or ethnic cleansing - can Europe provide an answer? LIT, Münster 2005, ISBN 3-8258-8494-5 .

- Reiner Zilkenat : “Volkstumsppolitik”, fascist secret services and the politics of the Sudeten German Party - On the prehistory of the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia in 1938. In: Circular 1 + 2/2008 of the AG Right-Wing Extremism / Antifascism at the federal executive of the party DIE LINKE (PDF; 1.6 MB ) .

Web links

- Národní archiv: Web exhibition: German anti-fascists from Czechoslovakia in archival documents (1933–1948) - edition of the project “Documentation of the fates of active Nazi opponents” based on government resolution No. 1081 of August 24, 2005, which was published after the end of the Second World War by the in Measures carried out by Czechoslovakia against the so-called enemy population were affected.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Bernd Mayer : Bayreuth in the twentieth century . Nordbayerischer Kurier , Bayreuth 1999, p. 71 .

- ↑ Reiner Zilkenat: “Volkstumsppolitik”, fascist secret services and the politics of the Sudeten German Party - On the prehistory of the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia in 1938. In: Circular 1 + 2/2008 of the AG Right-Wing Extremism / Antifascism at the federal executive of the party DIE LINKE , p. 18.

- ^ Emil Hruška: Sudeten German Chapter - Study on the origin and development of the Sudeten German union movement. German-Czech news dossier No. 2, Munich 2003, p. 7.

- ↑ a b c Reiner Zilkenat: “Volkstumsppolitik”, fascist secret services and the politics of the Sudeten German Party - On the prehistory of the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia in 1938. In: Circular 1 + 2/2008 of the AG Right-Wing Extremism / Antifascism at the Federal Executive Committee of the DIE LINKE party , p. 24f.

- ^ Emil Hruška: Sudeten German Chapter - Study on the origin and development of the Sudeten German union movement. German-Czech news dossier No. 2, Munich 2003, p. 50.

- ↑ The expulsion of the Germans from Eastern Europe using the example of Czechoslovakia - A Marxist position on a left taboo ( Memento of the original from November 4, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b Národní archive: Web exhibition: German anti-fascists from Czechoslovakia in archive documents (1933–1948) ( Memento of the original from November 28, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b Reiner Zilkenat: "Volkstumsppolitik", fascist secret services and the politics of the Sudeten German Party - On the prehistory of the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia in 1938. In: Circular 1 + 2/2008 of the AG Right-Wing Extremism / Antifascism at the federal executive board of the DIE LINKE party , p. 29f .

- ↑ Ralf Gebel: "Heim ins Reich!": Konrad Henlein and the Reichsgau Sudetenland (1938–1945). Munich 1999, p. 56.

- ↑ Werner Röhr: The "Fall Grün" and the Sudeten German Freikorps. 2007, p. 244.

- ^ Andreas Luh: The German Gymnastics Federation in the First Czechoslovak Republic. From folk club operations to popular political movement. Munich 2006, p. 417f.

- ↑ Martin Broszat: The Sudeten German Freikorps. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte , 9th year, issue 1, 1961, pp. 33f, 44f.

- ↑ a b Werner Röhr: The "Fall Grün" and the Sudeten German Freikorps. 2007, pp. 245f.

- ↑ Quoted in: Max Domarus: Hitler - Reden und Proklamationen 1932–1945 , Würzburg 1962, Volume 1, p. 905.

- ↑ a b Werner Röhr: The "Fall Grün" and the Sudeten German Freikorps. 2007, p. 246f.

- ↑ Martin Broszat: The Sudeten German Freikorps. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte , 9th year, issue 1, 1961, p. 32.

- ↑ a b Werner Röhr: The "Fall Grün" and the Sudeten German Freikorps. 2007, p. 247.

- ↑ a b Václav Kural, Václav Pavlíček: The so-called Second Republic. In: Zdeněk Beneš, Václav Kural (ed.): Understanding History - The Development of German - Czech Relations in the Bohemian Lands 1848–1948 , Prague 2002, p. 117.

- ↑ Martin Broszat: The Sudeten German Freikorps. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte , 9th year, issue 1, 1961, p. 35f.

- ↑ a b Martin Broszat: The Sudetendeutsche Freikorps. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte , 9th year, issue 1, 1961, p. 36f.

- ↑ a b Werner Röhr: The "Fall Grün" and the Sudeten German Freikorps. 2007, p. 249.

- ↑ a b Martin Broszat: The Sudetendeutsche Freikorps. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte , 9th year, issue 1, 1961, p. 47.

- ↑ Ralf Gebel: "Heim ins Reich!": Konrad Henlein and the Reichsgau Sudetenland (1938–1945). Munich 1999, p. 158.

- ↑ Martin Broszat: The Sudeten German Freikorps. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte , 9th year, issue 1, 1961, p. 39.

- ^ A b c Emil Hruška: Sudetendeutsche Kapitel - Study on the origin and development of the Sudeten German union movement. German-Czech news dossier No. 2, Munich 2003, p. 69.

- ↑ Adolf Hitler's telex from September 18, 1938, in: IMG, XXV, PS-388, p. 475, quoted from: Martin Broszat: Das Sudetendeutsche Freikorps. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte , 9th year, issue 1, 1961, p. 37.

- ↑ Martin Broszat: The Sudeten German Freikorps. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte , 9th year, issue 1, 1961, p. 37f.

- ↑ a b c Werner Röhr: The "Fall Grün" and the Sudeten German Freikorps. 2007, p. 250.

- ↑ Quoted in: Emil Hruška: Sudetendeutsche Kapitel - Study on the Origin and Development of the Sudeten German Union Movement , German-Czech News Dossier No. 2, Munich 2003, pp. 68f.

- ↑ Quoted in: Emil Hruška: Sudetendeutsche Kapitel - Study on the Origin and Development of the Sudeten German Union Movement , German-Czech News Dossier No. 2, Munich 2003, p. 69.

- ↑ Werner Röhr: The "Fall Grün" and the Sudeten German Freikorps. 2007, p. 252.

- ↑ Martin Broszat: The Sudeten German Freikorps. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte , 9th year, issue 1, 1961, p. 41f.

- ↑ Werner Röhr: The "Fall Grün" and the Sudeten German Freikorps. 2007, p. 251.

- ↑ Werner Röhr: The "Fall Grün" and the Sudeten German Freikorps. 2007, p. 250ff.

- ^ Emil Hruška: Sudeten German Chapter - Study on the origin and development of the Sudeten German union movement. German-Czech news dossier No. 2, Munich 2003, p. 70.

- ^ Jörg Osterloh: National Socialist Persecution of Jews in the Reichsgau Sudetenland 1938–1945. Munich 2006, p. 177.

- ^ Emil Hruška: Sudeten German Chapter - Study on the origin and development of the Sudeten German union movement. German-Czech news dossier No. 2, Munich 2003, p. 71.

- ↑ Tabular information from: Werner Röhr: Der "Fall Grün" and the Sudetendeutsche Freikorps , 2007, pp. 251f.

- ↑ a b c Emil Hruška: Sudeten German chapter. Study on the origin and development of the Sudeten German union movement. German-Czech news dossier No. 2, Munich 2003, pp. 70f.

- ↑ Quoted in: Emil Hruška: Sudetendeutsche Kapitel - Study on the Origin and Development of the Sudeten German Union Movement , German-Czech News Dossier No. 2, Munich 2003, p. 71.

- ↑ Werner Röhr: The "Fall Grün" and the Sudeten German Freikorps. 2007, pp. 252f.

- ↑ Martin Broszat: The Sudeten German Freikorps. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte , 9th year, issue 1, 1961, p. 42f.

- ↑ a b Werner Röhr: The "Fall Grün" and the Sudeten German Freikorps. 2007, p. 253.

- ↑ Werner Röhr: The "Fall Grün" and the Sudeten German Freikorps. 2007, pp. 253f.

- ↑ a b Werner Röhr: The "Fall Grün" and the Sudeten German Freikorps. 2007, p. 254.

- ↑ Martin Broszat: The Sudeten German Freikorps. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte , 9th year, issue 1, 1961, p. 46.

- ↑ Martin Broszat: The Sudeten German Freikorps. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte , 9th year, issue 1, 1961, p. 47f.

- ↑ a b Werner Röhr: The "Fall Grün" and the Sudeten German Freikorps. 2007, p. 256.

- ↑ Reiner Zilkenat: "Volkstumsppolitik", fascist secret services and the politics of the Sudeten German Party - On the prehistory of the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia in 1938. In: Circular 1 + 2/2008 of the AG Right-Wing Extremism / Antifascism at the federal executive board of the DIE LINKE party , p. 34.

- ↑ a b c Martin Broszat: The Sudetendeutsche Freikorps. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte , 9th year, issue 1, 1961, p. 49.

- ↑ a b c Werner Röhr: The "Fall Grün" and the Sudeten German Freikorps. 2007, p. 255.

- ^ Jörg Osterloh: National Socialist Persecution of Jews in the Reichsgau Sudetenland 1938–1945. Munich 2006, pp. 188f.

- ↑ Heiner Timmermann u. a. (Ed.): The Benes Decrees. Post-war order or ethnic cleansing - can Europe provide an answer? Münster 2005, p. 196.

- ^ Comité International de Dachau ; Barbara Distel , Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial (ed.): Dachau Concentration Camp 1933 to 1945 - Text and image documents for the exhibition , Munich 2005, p. 81.

- ^ Zdeněk Radvanovský (et al.): The Reichsgau Sudetenland. In: Zdeněk Beneš, Václav Kural (Hrsg.): Understanding History - The Development of German-Czech Relations in the Bohemian Countries 1848–1948 , Prague 2002, pp. 140f.

- ^ Rudolf Absolon: The Wehrmacht in the Third Reich. Structure, structure, law, administration. Volume IV: February 8, 1938 to August 31, 1939. Oldenbourg-Verlag, Munich 1998, p. 272.

- ↑ a b Life descriptions of the members of the Greater German Reichstag from the Sudeten German areas . In: The Greater German Reichstag 1938. Addendum . Berlin 1939, pp. 17–34.

- ^ René Küpper: Karl Hermann Frank (1898-1946). Political biography of a Sudeten German National Socialist. Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-486-59639-7 , p. 307.

- ^ Ernst Klee : Das Personenlexikon zum Third Reich , Frankfurt am Main 2007, p. 245.

- ^ René Küpper: Karl Hermann Frank (1898-1946). Political biography of a Sudeten German National Socialist. Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-486-59639-7 , pp. 116, 134f, 313ff.

- ^ Rudolf M. Wlaschek: Jews in Böhmen - Contributions to the history of European Jewry in the 19th and 20th centuries. Volume 66 of the Collegium Carolinum , Munich 1997, ISBN 3-486-56283-5 , p. 111.

- ^ Joachim Lilla , Martin Döring, Andreas Schulz: extras in uniform. the members of the Reichstag 1933–1945. A biographical manual. Including the national and national socialist members of the Reichstag from May 1924. Droste, Düsseldorf 2004, ISBN 3-7700-5254-4 , p. 360.

- ^ Joachim Lilla, Martin Döring, Andreas Schulz: extras in uniform. The members of the Reichstag 1933–1945. A biographical manual. Including the ethnic and National Socialist members of the Reichstag from May 1924. Droste, Düsseldorf 2004, ISBN 3-7700-5254-4 , p. 60.

- ^ Joachim Lilla, Martin Döring, Andreas Schulz: extras in uniform. the members of the Reichstag 1933–1945. A biographical manual. Including the ethnic and National Socialist members of the Reichstag from May 1924. Droste, Düsseldorf 2004, ISBN 3-7700-5254-4 , p. 72f.

- ^ Ernst Klee: The dictionary of persons on the Third Reich. Frankfurt am Main 2007, p. 324.

- ^ Joachim Lilla, Martin Döring, Andreas Schulz: extras in uniform. the members of the Reichstag 1933–1945. A biographical manual. Including the ethnic and National Socialist members of the Reichstag from May 1924. Droste, Düsseldorf 2004, ISBN 3-7700-5254-4 , p. 406.

- ^ Joachim Lilla, Martin Döring, Andreas Schulz: extras in uniform. the members of the Reichstag 1933–1945. A biographical manual. Including the ethnic and National Socialist members of the Reichstag from May 1924. Droste, Düsseldorf 2004, ISBN 3-7700-5254-4 , p. 466.

- ↑ Martin Broszat: The Sudeten German Freikorps. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte , 9th year, issue 1, 1961, p. 34f.

- ↑ Martin Broszat: The Sudeten German Freikorps. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte , 9th year, issue 1, 1961, p. 38 f.

- ↑ Martin Broszat: The Sudeten German Freikorps. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte , 9th year, issue 1, 1961, p. 38 f.

- ↑ Wolfgang Benz: History of the Third Reich, CH Beck, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-46765-2 , p. 162 f.

- ↑ Werner Röhr: The "Fall Grün" and the Sudeten German Freikorps. 2007, p. 242 f.

- ^ Circular decree of the Ministry of the Interior of the Czechoslovak Republic of August 24, 1945 on the regulation of Czechoslovak citizenship according to the decree of August 2, 1945 (PDF; 46 kB). In: Expulsion and expropriation laws, decrees and implementing provisions in Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, Yugoslavia between 1943 and 1949 , Hungarian Institute Munich , 2005. Quoted from: The expulsion of the German population from Czechoslovakia . Edited by the Federal Ministry for Displaced Persons, Bonn 1957, pp. 245-258.

- ↑ Heiner Timmermann u. a. (Ed.): The Benes Decrees. Post-war order or ethnic cleansing - can Europe provide an answer? Münster 2005, p. 275f.

- ↑ Property Index - Keyword Sudetendeutsches Freikorps , Source: Trial of the Major War Criminals before the International Court of Nuremberg. Nuremberg 1947, Vol. 23, pp. 137-142. , online at: www.zeno.org

- ^ Emil Hruška: Sudeten German Chapter - Study on the origin and development of the Sudeten German union movement. German-Czech news dossier No. 2, Munich 2003, p. 72.