Valentin submarine bunker

The submarine bunker Valentin , often also called the submarine bunker Farge , is a building in what is now the Bremer district of Rekum - at that time Farge -Rekum - on the Weser , which was used during the Second World War from 1943 to March 1945 Forced laborers , killing thousands. In the submarine bunker , type XXI submarines were to be built in section construction. It was the largest armaments project in the Navy . The bunker was about 95 percent complete; Due to the course of the war, the planned construction of the Type XXI boats could no longer be started.

Measured in terms of its area (35,375 m²), the bunker is the largest free-standing bunker in Germany and the second largest in Europe after the submarine repair yard Brest in France . One million tons of gravel and sand , 132,000 tons of cement and 20,000 tons of steel were used .

A part of the bunker was used by the German Armed Forces from 1960 to the end of 2010 as a part of the Wilhelmshaven marine material depot 2. Between May 2011 and November 2015 this part was converted into a memorial with a visitor center. To this end, the federal government and the state of Bremen each invested 1.9 million euros. On November 8, 2015, the memorial was opened as the Bunker Valentin memorial site . The part of the bunker that was used by the German Navy as a depot is accessible . The destroyed part of the bunker has been visible in a tunnel since the end of the renovation work. The rest of the ruin is closed for security reasons.

planning

Project

When the bombing raids on German shipyards increased and the production of submarines was severely restricted as a result, bomb-proof shipyards in bunkers were planned. A meter-thick shell layer (in the Valentin bunker in the form of a seven-meter prestressed concrete ceiling) was supposed to ensure that production could not be disrupted by Allied air raids.

Towards the end of 1942, Albert Speer , Minister of Armaments since February 1942, published the plan for one of the largest bunker shipyards. Bremen- Farge was chosen as the location because of the favorable infrastructure connection to the Weser and the enormous production capacities of the nearby Bremen shipyards. The bunker should after completion of the shipyard Bremer Vulkan for final assembly in sectional construction pipelined constructed of type XXI submarines be used. Another bunker construction called " Hornisse " was started in the port of Bremen for the AG Weser in order to manufacture submarine sections there. Other sections were to be produced in the " Wespe " bunker in Wilhelmshaven and then taken by ship to the Valentin bunker for final assembly.

The name was based on the initial letters of the locations: " V alentin" comes from V egesack , the location of the Vulkan shipyard. The submarine pen in Hamburg- F sink werder called " F ink II ," the bunker W aspen stand in W ilhelmshaven in K iel there was the submarine pen K ilian .

In anticipation of the imminent completion of the bunker, Grand Admiral Dönitz visited the construction site on April 22, 1944 and Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels on November 24, 1944. Goebbels came from Deschimag AG Weser shipyard in Gröpelingen by speedboat for a one-hour flying visit.

Production method

After completion, a submarine was to be launched in the bunker every 56 hours , which would have resulted in a monthly production of 14 boats. Plans from the end of 1944 envisaged that after the start of production in April 1945, three boats a month would initially be completed and from August 1945 the (preliminary) maximum capacity of 14 boats would be reached.

The sections of the boats were to be prefabricated in other factories - mainly in the Blohm & Voss , Deschimag AG Weser and Deschimag Seebeck AG shipyards - and assembled and fully equipped on an assembly line under the direction of Bremer Vulkan in the "Valentin" bunker . 13 assembly stations were planned, whereby station 13 was an approximately 8 m deep water basin with a subsequent exit to the Weser. Stations 12 and 13 were separated from the rest of the area by walls and sluice gates and could be flooded up to a height of 14 m.

After the boat floated up in station 12, it was moved sideways to station 13. After reaching the maximum water level of 14 m, stationary leak and function tests up to a depth of 22 m (keel of the boat) would have been possible in station 13.

Valentine 2

Since there was not enough space in the Valentin shipyard bunker with its 13 clock stations for equipping the submarines, the planning order for the "Valentin 2" bunker was placed in November 1944. The earthworks began in February 1945 and ended at the end of March 1945.

construction

The construction was planned and supervised by the Todt Organization . Since the start of construction in the spring of 1943, construction management has been carried out by the Agatz & Bock consortium , while Erich Lackner and Deschimag AG Weser were responsible for on-site management . For the delivery of the building materials, quays were created on the Weser and a branch line of the Farge – Schwanewede marine railway was built. 50 companies in two working groups were busy with the construction. The construction work took place practically under the eyes of the Allies, as numerous English and American aerial photographs show.

Between 10,000 and 12,000 forced laborers were brought in from the occupied territories and the Neuengamme concentration camp . They had to build the bunker in ten hour shifts. It is believed that 2,000 to 6,000 people were killed in the construction work, but more precise figures are difficult to determine. 1,700 deaths are registered. The names of the Polish and Russian dead were not taken into account. Many slave laborers died of malnutrition or physical exhaustion.

Camp for workers and prisoners

In the Bremen- Farge region with the villages of Schwanewede and Neuenkirchen , which are now in Lower Saxony , there were seven prisoner camps on an area of 6 by 2 km.

In 1937, the Gottlieb Tesch company from Berlin set up a residence camp for company employees on Waldweg (today An de Deelen ) in Lüssum . In addition, 300 “foreign workers” were initially added. As early as 1938, these were used in the construction of 78 underground bunkers for the gigantic fuel tank farm of the front company Wifo in Farge (Farge tank farm). In the vicinity of this construction site, on today's concrete road, the "Community Camp Tesch" was built in 1938, with barracks to accommodate around 2000 employees. Around 1941 there were around 400 forced laborers (prisoners of war).

In October 1940 , the Gestapo Bremen set up the first so-called work education camp , the AEL-Farge , in the “Community camp Tesch” on the construction site of the Wifo tank farm in Farge . The Gestapo rented the prisoners to the construction companies for forced labor. a. also on the construction site of the submarine bunker. In order to meet the excessive demand for labor (when there was a lack of construction machinery) for the construction of the submarine bunker, the Farge labor camp was established in 1943 as the third largest satellite camp of the Neuengamme concentration camp . Over 2,500 prisoners were brutally forced to do heavy labor on the construction site as SS work slaves . Many of them were housed in an unused oil tank of the marine oil tank farm, built in 1940, after its construction had ceased on July 3, 1941. There they were without daylight, malnourished and cramped in an inhuman way in a confined space under unbearable hygienic conditions. Other concentration camp prisoners had to live in barracks on the site of the construction site of the marine oil tank farm.

A workers' housing complex built in 1939, the “Marine Community Camp” made of wooden and stone barracks (including the “Wilhelmine” barracks) was used in 1944 to accommodate around 1400 forced laborers.

On a field near the submarine bunker construction site, the “Farge-Rekumer Feldmark” camp with 24 barracks was built in 1943 for approx. 1500 forced laborers (Soviet prisoners of war and prisoners of the Gestapo “labor education camp”) and approx. 600 marines ( Marine-Landesschützenenzug Farge, to guard the prison camps and the construction sites).

In Schwanewede, two large forced labor camps were set up around 1943, Heidkamp I and Heidkamp II, with a total of 36 barracks for around 2800 so-called "Eastern workers" and for Italian prisoners of war.

Bombing and end of construction

In early 1943, the area bombing of Bremen and the Deschimag AG Weser and Bremer Vulkan shipyards began. The bunker was not bombed, although the progress of construction was known to the Allies through aerial reconnaissance. Presumably it was more important to them that the construction site tied up material and manpower, which was withdrawn from other armaments projects. It was only shortly before commissioning, when the bunker was around 90% complete, that three air raids were carried out on it in 1945.

The first attack took place on February 9, 1945. The second on March 27, 1945, 18 specially equipped Lancaster B Mk.I (Special) bombers of the Royal Air Force flew four tall boys with 13 Grand Slams (10 t each) (5.4 t each) and twelve 454 kg bombs were armed. Two hits were recorded, two Grand Slams penetrated about 2 m deep into the 4.5 m thick ceiling, which is in the first stage of expansion. Both tore a hole about 8 m in diameter in the bunker ceiling, one of which can be seen in the picture opposite with armor hanging out, popularly known today as the “dead man” because of its shape. The construction work was then stopped. The majority of the victims of the bombing were French civil workers from the Service du travail obligatoire (STO). On March 30, 1945, an attack by the US Army Air Force took place , whose 2.5-ton bombs could not harm the bunker, but destroyed the surrounding unprotected infrastructure and sank the dredger , which was supposed to clear the breakthrough to the Weser. Construction did not resume and even post-attack cleanup was canceled a week later.

Building data

With a length of 419 meters, it is the longest building in Bremen; the second longest building is Speicher XI , located in the Überseestadt district of Bremen , at 403 meters.

- Length: 419 m (sometimes 426 m are also given)

- Width (east): 67 m

- Width (west): 97 m

- External height: 20–22 m

- External height with a raised ceiling: 30–33 m

- Interior height: 18 m

- Base area: 35,375 m²

- secured enclosed space: 520,000 m³

- Installed concrete: almost 500,000 m³

- Concrete thickness (ceiling, first expansion stage): 4.5 m

- Concrete thickness (ceiling, second expansion stage): 7 m

- Concrete thickness (outer walls): 4.5 m

Use after the war

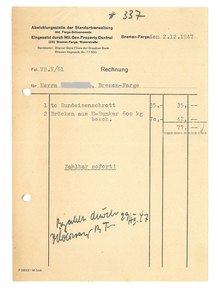

After approval by the Allies at the end of May 1945, workers from the construction companies involved began to dismantle the facilities. The construction site was handled in an orderly manner until 1949, with the administration office of the Farge-Schwanewede department, deployed by the US Military Government Property Control based in Farge, Weserstraße (today Unterm Berg), selling the remaining building materials and scrap metal to interested customers. When the management and administration of imperial assets, including armed forces assets, had passed into the hands of the Bremen Regional Finance Directorate in 1947, they also sold real estate from the bunker construction site to Farger business people (at Reichsmark prices), e.g. B. the "pump house" on the banks of the Weser to an electrician (demolished in 1998) and the building of the construction management (today Rekumerstr. 70) to a grocer. Between 1946 and 1949 the bunker was used by the RAF and the USAF for tests with special concrete-breaking bombs. The complete demolition was discussed several times, but never implemented, which failed mainly due to the contradiction of the new port director and former construction manager for the bunker, Arnold Agatz . In addition, the possible damage in the area would have become too great. It was assumed that the large collapsing masses would create an artificial earthquake , as a result of which the district of Rekum would be largely destroyed and the nearby Farge power station severely damaged. As a result, only smaller parts of the bunker, the plunge pool and the exit pool were blown up by the English.

In 1948, the Senator for Civil Engineering planned to convert the bunker into a large hill using rubble and earthworks to use it as a parkland. Around 800,000 m³ of material would have been required for the complete leveling of the site. Due to the resulting costs of around one million marks, the Senate finally dropped the project. Instead, the Weser side of the bunker area developed completely independently into a popular swimming, fishing and camping site.

In the 1950s, the bunker received public attention again, although it was referred to as a “miracle” or “eighth wonder of the world” in terms of technical performance and its size. Even a corpse found in the foundation of the bunker on June 28, 1957, which was obviously a deceased slave laborer, did not lead to any further discussion of the negative aspects of the bunker construction. The focus was on a further pragmatic use of the gigantic building. The bunker building was to be used as a large cold store or converted into a nuclear reactor (1957). Both ideas, however, as well as the plan to build a leisure facility, were abandoned for cost reasons. After the rearmament , it was intended as a depot for American nuclear weapons, which was also never implemented.

In October 1960 the Bundeswehr decided to use the bunker as a naval material depot . Four years later, the repair work began on around 40% of the bunker, which was converted into a naval depot for the Bundeswehr. Spare parts, on-board equipment and nautical accessories of various types of ships have been stored here since October 1, 1966, and materials from various on-board helicopters were added later. As a tank training area, the area of the former satellite camp had been part of the military garrison training area since the late 1950s. This partial depot of the Wilhelmshaven marine material depot 2 was abandoned in 2010.

The foundations of the bunker are based on Lauenburg clay , which is characterized by high strength and stability. Therefore, instead of a complete foundation plate, only foundation strips were sufficient for the foundation. These are between 6.50 and 15 meters deep and between 11 and 12 meters wide. Even today, measurements are made of the subsidence of the structure in the ground in order to gain unique empirical values for the improvement of static calculations.

Memorial

After the bunker had long been forgotten due to secrecy and military cordoning off, the history of the forced laborers has gradually been dealt with since the 1980s. In 1975, the Bremen administrative officer Rainer Habel found a major request to the Senate for mass graves in Farger Heide in old parliamentary protocols. From his research, the radio production "Nobody leaves the camp alive" for Radio Bremen was created in 1981 , which brought the fate of the forced laborers back into the consciousness of a broader public.

Habel founded the “Flowers for Farge” initiative, which maintained contact with former prisoners such as Lucien Hirth (1923–2008) and André Migdal , who had been taking regular commemorative trips (Pélérinagen) to the bunker for many years. The initiative increasingly campaigned for the creation of a memorial for the former forced laborers of the bunker construction site.

memorial

After lengthy discussions, a memorial for the victims of the bunker building was inaugurated on September 17, 1983, a concrete sculpture by the Bremen artist Fritz Stein with the name Destruction through Labor . It stands on the former route of the Farge-Schwanewede naval railway outside the bunker area fenced in by the Bundeswehr, right next to the entrance gate to the military facilities.

Initiatives arose to inform the public and the Bundeswehr began to abandon military secrecy and shielding in favor of limited public relations. After protests, she had an information board put up on the blasted round bunker in which concentration camp prisoners were housed in 1985, and in April 1995 the senior officer of the Bundeswehr Schwanewede had a boulder erected to commemorate the dead of the subcamp on the 50th anniversary of the end of the war. It was replaced by a newer one in 2008. Since 1990, some site managers have allowed civilian visitors to visit the bunker and assigned an employee from the depot for tours.

Cultural event

Readings by former prisoners were now allowed to take place in the unrenovated part of the bunker and this led to the fact that this cultural program was expanded. On May 7, 2000, 55 years after the end of the war and the liberation from the prisoner camps, André Migdal, for example, spoke in the Valentin submarine bunker: his Cantate pour la vie premiered there. Between 1999 and 2004 the play The Last Days of Mankind by Karl Kraus , directed by Johann Kresnik from Theater Bremen, was performed in the unused part of the ruin . Around 40,000 theater guests attended the performances.

In 1999, the Bundeswehr made a material barrack available for exhibition purposes. Since the beginning of 2002, distinctive places such as the former grounds of the satellite camp and the “Farge labor education camp” as well as graves as stations on a “history trail” have been marked with steles. Since 2005, the Blumenthal school center has been running a commemorative run at the end of April from the Weser dyke at the bunker across Lagerstraße to the former labor education camp. The “History Trail” association and the “Peace School Bremen” regularly organize guided tours through the bunker and the camp grounds. In 2005, Valentin was the first bunker in the state of Bremen to be listed as a historical monument . In view of the plans to sell the bunker, the Bremen Senate with Mayor Jens Böhrnsen and Mayor Karoline Linnert visited the “Valentin” bunker on April 15, 2008 together with Brigadier General Wolfgang Brüschke. The focus of the discussions was on an appropriate re-use of the building. The Senate spoke out in favor of erecting a memorial in the bunker for the forced laborers who died in the construction. In the same year a memorial seminar took place in Bremen, which addressed the bunker as a future memorial. On March 3, 2009, the Bremen Senate decided to provide 150,000 euros for the creation of a memorial concept. The Bremen State Center for Political Education was commissioned to prepare for the establishment of a central memorial and documentation center.

memorial

Bremen received 1.9 million euros from the federal government to build a memorial in the former submarine bunker Valentin from 2011 to 2015 and doubled this amount from state funds.

The renovation of the former depot began on May 8, 2011, and in November 2015 the “Bunker Valentin Bunker” memorial finally went into operation. Since then, a circular route with 26 information stations has led through and around the "Valentin" bunker. Part of the circular route is the new information center on the south side. A media table provides information about the development of the armaments landscape since 1932, and an exhibition provides additional information. A media guide can also be borrowed there. In addition, the regional center for political education offers seminars and tours for schoolchildren, students and adults. The aim is to "make this gigantic relic of the National Socialist regime accessible to future generations as a symbol of megalomania and inhuman ideology."

At the end of December 2011, a dispute arose between the BImA as the owner and the Bremen State Office for Monument Preservation. In order to cover the operating costs, the BImA would like to “rent space for storage in addition to a three-storey side section in the large hall”. The monument office contradicted this: That would destroy the character of the huge hall, “one could no longer perceive the dimension in its entirety. You have to be able to walk through it. "

The Denkort can be reached with the bus line 90 of the Bremer Straßenbahn AG . The closest stop is Rekumer Siel.

owner

On December 31, 2010, the Bundeswehr stopped using the bunker. Since then, the complex has been managed by the Federal Agency for Real Estate Tasks (BImA). This tries to use the front part of the bunker economically. When the bunker was put up for sale on the Internet, Mayor Jens Böhrnsen warned : “You can't put this monstrous monument on a sales list like any other property”. On January 10, 2011, Böhrnsen signed a usage agreement with the BImA for the shared use of the bunker.

The roof of the depot part of the bunker has been used for a photovoltaic system since 2012.

See also

- Documentation and learning location Barrack Wilhelmine

- Bremen bunker murder

- Bremen at the time of National Socialism

- Farge # Farge during National Socialism

literature

- Jan-Friedrich Heinemann, Ingo Hensing, Karin Puzicha, Klaus Schilder. The submarine bunker 'Valentin'. Contribution to the “German History” school competition for the Federal President's Prize (supervision: Klaus-Peter Zyweck). Photocopied typescript. School center Lehmhorster Straße Bremen-Blumenthal. 1983

- Michèle Callan: Forgotten Hero of Bunker Valentin. The story of Harry Callan. Edition Falkenberg: Rotenburg / Wümme 2018

- Peter-Michael Meiners: The camps of the “Valentin” submarine bunker construction site. Osterholz-Scharmbeck 2015, Reineke printing company

- Gerhard Koopmann: In the shadow of the bunker. epubli , Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-8442-7565-0 (collection of contemporary witness reports that have been edited in literary terms).

- Marc Buggeln: The “Valentin” submarine bunker. Naval Armaments, Forced Labor, and Remembrance. Published by the State Center for Political Education Bremen . Edition Temmen , Bremen 2010, ISBN 978-3-8378-4004-9 .

- Marc Buggeln: The Valentin bunker. On the history of the construction and the storage system . Ed .: State Center for Political Education in Bremen. 2002 ( bildung.bremen.de [PDF] brochure).

- Marc Buggeln: The construction of the “Valentin” submarine bunker, the use of forced labor and the participation of the population . ( denkort-bunker-valentin.de [PDF] extended and updated version of the text from 2002).

- Barbara Johr , Hartmut Roder : The bunker: An example of National Socialist madness. Bremen-Farge 1943-45 . Edition Temmen , Bremen 1989, ISBN 3-926958-24-3 .

- Nils Aschenbeck , Hartmut Roder: Factory for eternity. The submarine bunker in Bremen-Farge. Junius Verlag, Hamburg 1995, ISBN 3-88506-238-0 . (Photographs: Rüdiger Lubricht)

- Raymond Portefaix, André Migdal , Klaas Touber : Hydrangeas in Farge. Survival in the "Valentin" bunker. Ed .: Bärbel Gemmeke-Stenzel, Barbara Johr. Donat Verlag, Bremen 1995, ISBN 3-924444-88-9 .

- Dieter Schmidt, Fabian Becker: Bunker Valentin: War economy and forced labor. Bremen-Farge 1943-45 . Edition Temmen, Bremen / Rostock 2001, ISBN 3-86108-288-8 .

- Rainer Christochowitz: The Valentin submarine bunker shipyard. The submarine section construction, the concrete construction technology and the inhumane use from 1943 to 1945 . Donat Verlag, Bremen 2000, ISBN 3-934836-05-4 .

- Heiko Kania: New findings on the number of victims and camps in connection with the construction of the Valentin submarine shipyard bunker in Bremen-Farge . In: Labor Movement and Social History . 2002 ( Sozialgeschichte-bremen.de [PDF]).

- Heiko Kania, The Forced Labor System of the Third Reich in World War II. Shown using the example of the suburb of Schwanewede near Bremen, student thesis 1997

- Christian Siegel: "The submarine bunker is a beast". The bunker shipyard in Bremen-Farge as part of total warfare . State Center for Political Education Bremen, Bremen 2004.

- Peter Michael Meiners: Armaments and Forced Labor. Results of a search for clues. Farge-Rekum-Neuenkirchen-Schwanewede . Self-published, Ritterhude 2017

- Rainer Hager: Wasserberg? History and construction of a Bremen-Farge tank farm by Wifo (economic research company). undated Illustrated typescript. Own print, Bremen around 2004.

- Jens Genehr: Valentin . Golden Press, Bremen 2019, ISBN 978-3-9819880-5-5 ( graphic novel ).

Movies

- depot demon denkort - the submarine bunker in Bremen-Farge; Film by Silke Betscher, Katharina Hoffmann and Wolfgang Wortmann with the support of learning groups from the Blumenthal school center. Distribution: State Center for Political Education Bremen (Premiere: April 25, 2008).

- Living with the bunker : The submarine bunker "Valentin", film by Christin Bamberg and Karen Dahlke, Bremen University of Applied Sciences - international course in specialist journalism 2009, bachelor thesis (duration 30 min.)

- Mysterious places: Hitler's submarine bunker. Film by Susanne Brahms, Bremedia Production (first broadcast: February 10, 2014).

Web links

- Bunker Valentin , an exhibition of the State Center for Political Education Bremen

- Association of Documentation and Memorial Site History Trail Lagerstraße / U-Boot-Bunker Valentin e. V. at www.geschichtslehrpfad.de

- Documentation and learning location Baracke Wilhelmine at www.baracke-wilhelmine.de

- Private pictures from inside the bunker

- The “Valentin” submarine bunker yard on www.relict.com

- Submarine bunker Valentin, Bremen-Farge on geschichtsspuren.de

- Charcoal drawings by Robert Schneider on www.bilder-der-arbeit.de

- Günter Beyer: "Have a bunker, looking for a concept" , contribution to Deutschlandradio Kultur on September 1, 2008

- Website of the International Peace School Bremen on the "Valentin" bunker

Individual evidence

- ↑ For historical reasons, the bunker is often assigned to Farge . But it is located in the Bremer district of Rekum . See Rekum at OpenStreetMap

- ↑ Radio Bremen (May 9, 2011), also Denkort Bunker Valentin , on February 6, 2014.

- ↑ Guided tours are also possible again in the interior of the bunker. In: Denkort Bunker Valentin . January 30, 2013.

- ↑ thougts bunker Valentin: 70 years ago: April 1944 - Doenitz inspected the bunker construction site. March 3, 2014, accessed August 17, 2018 .

- ^ Fritz Peters: Twelve Years of Bremen, 1933-1945. A chronicle . Ed .: Historical Society in Bremen. Bremen 1951, p. 275 .

- ↑ “The journey takes place in fine weather, takes about two hours and gives me wonderful physical and mental refreshment. A giant submarine bunker is visited near Vegesack, some of which has already been completed. It has a concrete ceiling of 7 m and thus seems to be immune to the most modern enemy bombs. The building has a real mammoth character. 8,000 workers, especially concentration camp convicts and Soviet prisoners of war, are working on it. [...] The return trip to Vegesack itself is again very nice. ”Joseph Goebbels: Dictation of November 25, 1944 . In: Elke Fröhlich (Ed.): The diaries of Joseph Goebbels. Part II Dictations 1941-1945, October to December 1944. On behalf of the Institute for Contemporary History and with the support of the Russian State Archives Service. Edited by Jana Richter and Hermann Graml. tape 14 . KG Saur, Munich 1996, p. 275-277 .

- ↑ Eike Lehmann: 100 years of shipbuilding society . Springer , Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-540-64150-5 , pp. 214 .

- ↑ Johr / Roder, pp. 22-26.

- ↑ Marc Bruggeln: The Valentin submarine pens . In: Inge Marszolek, Marc Buggeln (Ed.): Bunker. Place of war, refuge, memory space in the Third Reich . Frankfurt am Main 2008, ISBN 978-3-593-38603-4 , pp. 111 ff .

- ↑ State Archives Bremen Sign. 4,64 / 6-376

- ^ Franz Hochenauer: eyewitness report . In: Jan-Friedrich Heinemann, Ingo Hensing, Karin Puzicha, Klaus Schilder. (Ed.): The submarine bunker 'Valentin'. Contribution to the “German History” school competition for the Federal President's Prize (supervision: Klaus-Peter Zyweck). Photocopied typescript. School center Lehmhorster Straße Bremen-Blumenthal . 1983, p. 14 .

- ↑ Bremen's longest building. Bunker Valentin measures 419 meters. In: Weser-Kurier , May 26, 2012, p. 12.

- ↑ State Archives Bremen Sign. 4,64 / 6-231

- ^ Weser-Kurier , October 13, 1955.

- ^ Bremer Nachrichten , June 29, 1957.

- ↑ Christochowitz, p. 70 f.

- ↑ Lars Oliver Windmann: Former submarine bunker shipyard "Valentin". gottfired.jimdo.com, Retrieved September 18, 2019 .

- ↑ a b The "Flowers for Farge" initiative . In: Silke Wenk (Ed.): Places of memory made of concrete. Bunkers in cities and landscapes . Ch. Links Verlag, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-86153-254-9 , p. 174 u. a . ; limited preview in Google Book search

- ↑ Description ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) on the Neuengamme concentration camp website .

- ↑ "The last days of humanity" in the bunker on Spiegel Online , April 22, 1999.

- ^ Monument database of the LfD

- ↑ Press release of the Bremen Senate , April 15, 2008.

- ↑ Press release of the Bremen Senate , September 11, 2008.

- ↑ Press release of the Bremen Senate , March 3, 2009.

- ↑ Framework agreement signed for the use of the former Valentin submarine bunker. Senate Press Office, January 10, 2011, accessed January 12, 2011 .

- ↑ Speech by Minister of State for Culture Bernd Neumann at the opening event of the "Bunker Valentin think place". bundesregierung.de, May 8, 2011, accessed on September 18, 2019 .

- ↑ Denkort Bunker Valentin: Since May 2011 the official start of the memorial project . State Center for Political Education; accessed on February 6, 2014.

- ↑ Nordsee-Zeitung , January 5, 2012, p. 7.

- ↑ The bunker concept is in place . In: Weser-Kurier , September 8, 2010, p. 9.

- ↑ JF Heinemann u. a .: The submarine bunker "Valentin". Retrieved September 13, 2018 .

- ^ Hitler's submarine bunker. ( Memento from February 21, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Radio Bremen .

Coordinates: 53 ° 13 ′ 0 ″ N , 8 ° 30 ′ 15 ″ E