Riots on February 6, 1934

The riots on February 6, 1934 followed a large anti-government demonstration in Paris . In street battles succeeded almost members of the right-wing leagues, the Palais Bourbon to storm where precisely the Chamber of Deputies met. The police used firearms, 15 demonstrators were killed and over 2,000 injured. Triggered the riots were a corruption affair and any related dismissal of the Paris police prefect . As a result, the left-wing government Édouard Daladier resigned. It was followed by a cabinet of the Union nationale under the conservative Gaston Doumergue , in which the socialist Section française de l'Internationale ouvrière (SFIO) no longer took part. The unrest of February 6, 1934 is considered a sign of crisis in the Third Republic .

prehistory

General symptoms of crisis

In 1934 France was in crisis. The country suffered badly from the global economic crisis , which only started in autumn 1931. Gross domestic product and foreign trade fell, prices fell due to ongoing deflation , and unemployment rose (albeit less catastrophic than in Germany and the USA, for example: it was not until 1935 that France had over a million people without work). The governments that had been formed by the left under the leadership of the Parti radical since the May 1932 elections tried to avoid a budget deficit despite falling tax revenues and increasing social spending, and this pro-cyclical austerity policy exacerbated the crisis. The unsuccessful governments succeeded one another in quick succession: From June 1932 to February 1934, France was ruled by six different cabinets; the left-wing governments, unlike the later Popular Front, never had a stable majority.

Foreign and financial circumstances created further difficulties. In June 1932, France, represented by the left-wing Prime Minister Édouard Herriot , gave up its claim to German reparations payments at the Lausanne Conference . However, the country was still obliged to pay war debts to Inter allies, which it had always met with reparations income since 1926. France has refused to pay the United States since December 1932. Relations with the United States were sensitive charged - of all things in the moment with the takeover of the Nazis was threatened again in Germany France safety. Signs of this were Germany's withdrawal from the Geneva Disarmament Conference and the League of Nations in October 1933 and its non-aggression pact with Poland of January 1934, which devalued the Franco-Polish assistance pact of 1921 in terms of security policy.

Stavisky affair

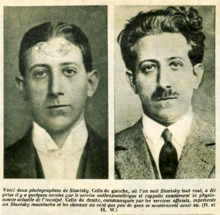

In this situation, a major scandal contributed to the further de-legitimization of the Third Republic's parliamentary system. Alexandre Stavisky , a fraudster of Jewish-Ukrainian origin, whose family had immigrated to France in 1898, had begun in 1933, in a pyramid scheme, to issue cash orders to the Crédit municipal de Bayonne , which he founded. The damage amounted to 200 million francs; the radical socialist mayor of Bayonne , Joseph Garat, knew of the fraud; Pierre Darius, editor of the radical socialist local newspaper Midi , was involved. In January 1934 the fraud was discovered and Garat was arrested. Stavisky himself fled; he was found shot dead in Chamonix on January 9, 1934 . The police found suicide, which met with widespread skepticism in the public.

The scandal immediately had political implications. The radical socialist colonial minister Albert Dalimier resigned on January 9, 1934 because he had recommended Stavisky's cash orders as a safe investment. At the same time, a dispute arose within the Paris Securities and Exchange Commission about who would be responsible for admitting the worthless papers. One of the accused was Georges Pressard, a brother-in-law of the radical socialist Prime Minister Camille Chautemps . This also gave him the reputation of having favored Stavisky's fraud.

The closeness of Stavisky to politicians of the Parti radical , who should have covered him for years, was emphasized especially in right-wing and right-wing radical circles. His Jewish origin was repeatedly pointed out, which gave the outrage an anti-Semitic character. The agitation came from the leagues, anti-parliamentary groups that were partly oriented towards Italian fascism and partly monarchist . Mention should be made of the Jeunesses patriotes of the champagne manufacturer Pierre Taittinger (founded 1926), the Solidarité française of the perfume manufacturer François Coty (founded 1933), the Mouvement Franciste (1933), the Croix de Feu (Feuerkreuzler) of Colonel François de La Rocque (founded 1926), the apolitical Redressement français of the oil magnate Ernest Mercier (founded 1926) and the Camelots du roi , the youth organization of Action française founded in 1908 . In January 1934, these organizations repeatedly called for demonstrations against what they believed to be a corrupt parliamentary regime, with slogans such as “à bas les voleurs!” (“Down with the thieves!”) And “Les députés à la lanterne!” (“Deputies to the lantern! ") were called. The demonstrations took place despite a police ban, which is why the first violent clashes with the police occurred on the Grands Boulevards in Paris. 32 police officers were injured and 1,520 demonstrators were provisionally arrested.

In the meantime , articles about real or alleged involvement of government politicians in the scandal have appeared in bourgeois newspapers, especially in the high-circulation Paris Soir . Personalities from the moderate right also took part in this agitation, such as Chamber Members Philippe Henriot and Jean Ybarnégaray from the nationalist Fédération républicaine and André Tardieu from the right-wing liberal Alliance démocratique (AD). However, they did not succeed in setting up a committee of inquiry, as the stable left majority made up of the SFIO, Parti radical and their allies voted unanimously against it. The fact that Chautemps finally resigned on January 27 was not only due to right-wing agitation, but to another scandal in which his Justice Minister Eugène Raynaldy was involved.

The dismissal of Chiappes

Chautemps' successor in the office of prime minister, the radical socialist Édouard Daladier, put together his cabinet on January 30th, in which two AD ministers were also represented. In order to retain the support of the socialists, he dismissed the Paris Prefect of Police, Jean Chiappe, on February 3rd. He had been in office since 1927 and had a reputation for cracking down on left-wing extremists much more severely than against the right-wing extremist leagues with which he sympathized. Therefore, he was considered the entire French left as "Bête noire". In addition, it was said that he had intentionally not passed on material that further incriminated Stavisky.

After all, on February 4 , he successfully suppressed another mass demonstration by the Union Nationale des Combattants , a veterans' association . Daladier offered him the post of resident in Morocco , but Chiappe refused. In the dispute over Chiappe's dismissal, the two ministers of the AD resigned, the Conseil Municipal of Paris, the municipal council dominated by supporters of the leagues, protested sharply on February 5 against the “beheading” of the city and the Seine-et-Marne department . At the same time it issued an appeal to the Parisians, in which it said: “In contempt for the interests of order and the peace of Paris, politics brutally sacrificed your prefects”.

Rumors made the rounds that the Marxism-friendly government was planning to use the military against the city of Paris and was preparing assassinations. The leagues now called for another large demonstration in front of the Palais Bourbon on February 6, where Daladier put himself up for a vote of confidence: One wanted to "fight to win or to die !!" A communist veterans association also mobilized its members against them Government and to demonstrate for an arrest of Chiappes.

course

On the evening of February 6, 30,000 members of leagues and veterans' associations, including twenty parish councilors, marched on the Place de la Concorde and surrounded the Palais Bourbon. A street battle began around 7 p.m. when demonstrators tried to break the police chain on the Pont de la Concorde and storm parliament. The police made use of firearms and deployed their cavalry units, demonstrators threw stones and cut the tendons of police horses with razors. De La Rocque, who had led his Croix de Feu from the south through the Faubourg Saint-Germain to Parliament, gave no order to attack, otherwise the demonstrators would have managed to storm the building. The street battle lasted until around midnight and killed 15 demonstrators, around 2,000 were injured and numerous ringleaders were arrested.

Commentary on the events in the press on February 7th was consistently negative. Daladier and his cabinet were denounced as "gouvernement d'assassins" ("murderous government"), "le gouvernement de M. Daladier a provoqué [...] la guerre civile" ("the government of Monsieur Daladier has provoked the civil war ") . Although he had won the vote of confidence the night before, Daladier resigned on February 7 after just nine days in office.

The unrest continued on February 7, when a large police presence cordoned off the area around Place de la Concorde and enforced a curfew . Numerous demonstrators and onlookers were injured and there were more deaths.

consequences

President Albert Lebrun entrusted seventy-year-old Gaston Doumergue with forming a government. He put together a cabinet of the Union nationale that ranged from the Radical Socialists to the Fédération républicaine . The SFIO no longer supported this government, the left-wing alliance that had gained a majority in 1932 had failed. The republic had moved to the right again - Dominique Borne and Henri Dubief interpret this shift in power as a late victory of Tardieu, who was defeated by the radical socialist Édouard Herriot in the 1932 elections .

The riots were widely perceived as a fascist coup attempt , which according to the latest research they were not: the actions of the individual leagues were too poorly coordinated and their goals too unclear. In the SFIO and the Parti communiste français (PCF) in particular , this perception was widespread and led to both parties cooperating more closely. The initiative for this came from the SFIO and was initially rejected by General Secretary Maurice Thorez with reference to the Comintern's thesis of social fascism . On February 12th, however, SFIO, PCF, their affiliated trade union CGTU and the French League for Human Rights called for a peaceful general strike in defense of the republic. With the Franco-Soviet assistance treaty of May 1935, the Soviet Union completely abandoned the allegation of social fascism. Now the candidates of the PFC were allowed to practice "défense républicaine", that is, they waived in the second ballot in favor of the SFIO applicant, if his election seemed more promising. This made possible the Front Populaire , which won a majority in the elections of 1936 and elected Léon Blum, France's first socialist prime minister.

Another consequence of the “fascist attempted coup” was the PCF's own defense: They tried to build up a powerful party force, the “auto-défense des masses” (“self-defense of the masses”), which did not recruit 1,000 activists. Although the party leadership officially banned the use of weapons, the buildings of the CGTU union and the party newspaper L'Humanité were militarily secured, and those working there armed themselves with clubs, machine guns and flamethrowers. On the other hand, the leagues, feeling just as threatened, increased their secret arsenals and prepared for a communist attack. In March 1934, the Jeunesses patriotes appointed Marshal Louis Hubert Lyautey , a war hero of the Rif War , to be their commander-in-chief in the event of a communist uprising. The self-defense measures of the French extremists against an alleged or real threat from the other never reached the extent of the civil war-like clashes that had shown a few years earlier at the end of the Weimar Republic .

Overall, the unrest of February 6, 1934 is considered a symptom of the crisis in the Third Republic. They showed the increasing division of the political system between right and left and an increase in power of the extremists on both sides. At the same time, they also revealed the weakness of the center loyal to the republic - for the first time a government had to give in to pressure from opponents of the republic.

Web links

- 6 février 1934 on herodote.net

Individual evidence

- ↑ Dominique Borne and Henri Dubief: La crise des années 30 1929-1938. (= Nouvelle histoire de la France contemporaine, vol. 13). Editions du Seuil, Paris 1989, pp. 21–37 and 79 f .; Andreas Wirsching : From World War I to Civil War? Political extremism in Germany and France 1918–1933 / 39. Berlin and Paris in comparison . Oldenbourg, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-486-56357-2 , p. 363 f. and 367 f. (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ^ Jean-Baptiste Duroselle : Politique extérieure de la France. La decadence (1932-1939). Imprimerie nationale, Paris 1979, pp. 29-75.

- ^ Paul Jankowski: Stavisky. A Confidence Man in the Republic of Virtue. Cornell University Press, New York 2002, pp. 139 f. ( Available here on Google.books.)

- ^ Roland Höhne: Stavisky scandal . In: Carola Stern , Thilo Vogelsang , Erhard Klöss and Albert Graff (eds.): Dtv lexicon on history and politics in the 20th century . dtv, Munich 1974, Vol. 3, p. 768; Dominique Borne and Henri Dubief: La crise des années 30 1929–1938. (= Nouvelle histoire de la France contemporaine, vol. 13). Editions du Seuil, Paris 1989, p. 109.

- ↑ Dominique Borne and Henri Dubief: La crise des années 30 1929-1938. (= Nouvelle histoire de la France contemporaine, vol. 13). Editions du Seuil, Paris 1989, p. 110.

- ↑ Dominique Borne and Henri Dubief: La crise des années 30 1929-1938. (= Nouvelle histoire de la France contemporaine, vol. 13). Editions du Seuil, Paris 1989, p. 110; Andreas Wirsching: From World War I to Civil War? Political extremism in Germany and France 1918–1933 / 39. Berlin and Paris in comparison . Oldenbourg, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-486-56357-2 , p. 594 (accessed from De Gruyter Online).

- ^ Roland Höhne: Stavisky scandal . In: Carola Stern, Thilo Vogelsang, Erhard Klöss and Albert Graff (eds.): Dtv lexicon on history and politics in the 20th century . dtv, Munich 1974, Vol. 3, p. 768; Dominique Borne and Henri Dubief: La crise des années 30 1929–1938. (= Nouvelle histoire de la France contemporaine, vol. 13). Editions du Seuil, Paris 1989, p. 110.

- ↑ Rudolf von Albertini : France from the Peace of Versailles to the end of the Fourth Republic 1919-1958 . In: Theodor Schieder (ed.): Handbook of European history . Vol. VII / 1. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1979, p. 451.

- ↑ Andreas Wirsching: From World War to Civil War? Political extremism in Germany and France 1918–1933 / 39. Berlin and Paris in comparison . Oldenbourg, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-486-56357-2 , pp. 470 and 552 (here the quote). (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ^ "Au mépris des intérêts de l'ordre et de la paix de Paris, la politique a brutalement sacrifié vos [...] préfets". Andreas Wirsching: From World War I to Civil War? Political extremism in Germany and France 1918–1933 / 39. Berlin and Paris in comparison . Oldenbourg, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-486-56357-2 , p. 472 (accessed from De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Andreas Wirsching: From World War to Civil War? Political extremism in Germany and France 1918–1933 / 39. Berlin and Paris in comparison . Oldenbourg, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-486-56357-2 , p. 472 (accessed from De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Dominique Borne and Henri Dubief: La crise des années 30 1929-1938. (= Nouvelle histoire de la France contemporaine, vol. 13). Editions du Seuil, Paris 1989, p. 111.

- ↑ The number at 6 février 1934 on herodote.net , accessed on October 21, 2015.

- ↑ Dominique Borne and Henri Dubief: La crise des années 30 1929-1938. (= Nouvelle histoire de la France contemporaine, vol. 13). Editions du Seuil, Paris 1989, p. 111 f.

- ↑ Dominique Borne and Henri Dubief: La crise des années 30 1929-1938. (= Nouvelle histoire de la France contemporaine, vol. 13). Editions du Seuil, Paris 1989, p. 111 f. (here the first quote); Andreas Wirsching: From World War I to Civil War? Political extremism in Germany and France 1918–1933 / 39. Berlin and Paris in comparison . Oldenbourg, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-486-56357-2 , p. 474 (here the second quote) (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Dominique Borne and Henri Dubief: La crise des années 30 1929-1938. (= Nouvelle histoire de la France contemporaine, vol. 13). Editions du Seuil, Paris 1989, p. 111 f.

- ↑ Dominique Borne and Henri Dubief: La crise des années 30 1929-1938. (= Nouvelle histoire de la France contemporaine, vol. 13). Editions du Seuil, Paris 1989, p. 111 f.

- ↑ Andreas Wirsching: From World War to Civil War? Political extremism in Germany and France 1918–1933 / 39. Berlin and Paris in comparison . Oldenbourg, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-486-56357-2 , p. 558 (accessed from De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Rudolf von Albertini: France from the Peace of Versailles to the end of the Fourth Republic 1919-1958 . In: Theodor Schieder (ed.): Handbook of European history . Vol. VII / 1. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1979, p. 451 f.

- ↑ Andreas Wirsching: From World War to Civil War? Political extremism in Germany and France 1918–1933 / 39. Berlin and Paris in comparison . Oldenbourg, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-486-56357-2 , p. 571 ff. And 577 f. and 601 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Dominique Borne and Henri Dubief: La crise des années 30 1929-1938. (= Nouvelle histoire de la France contemporaine, vol. 13). Editions du Seuil, Paris 1989, p. 112 f.