Vampire (munch)

|

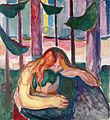

| vampire |

|---|

| Edvard Munch , 1893 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 80.5 × 100.5 cm |

| Gothenburg Art Museum |

Vampire ( Norwegian Vampyr ) is a picture motif by the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch , which he executed in six paintings between 1893 and 1895 and repeated in five other paintings in a later creative phase between 1916 and 1918. In addition, two lithographs were made in 1895 . It is one of the central motifs in the painter's work and belongs to his frieze of life .

In the center of the picture is a woman with orange-red hair bending over the neck of a man who is leaning towards her. According to Munch's explanation, the woman kisses the man on the neck. The reference to vampirism was only made by an interpretation of his friend Stanisław Przybyszewski , who also coined the title vampire . Munch originally called the motif love and pain .

Image description

A man bends over against a woman's body. She hugs him and in turn bends over his neck, into which she presses her face. Her long hair falls down in strands and partially covers the man. The two figures are on the image axes, which gives them a monumental character. They merge into a pyramid shape . The incidence of light causes shadows to rise behind them, which frame the contours of the two figures. The colors of the picture are determined by the woman's red-orange hair and the dark blue-violet shadows typical of Munch. In their darkness the figures seem to dissolve.

variants

As with many of his central works, Munch painted the motif several times, see also the list of paintings by Edvard Munch . Between 1893 and 1895, a total of six pictures with the title Vampire were created . Two oil paintings and one pastel are in the Munch Museum Oslo . An oil painting from 1893 is on display at the Gothenburg Art Museum. Two other versions are privately owned.

Between 1916 and 1918 Munch painted five more versions of the motif, some of which are set in the vicinity of a forest. Four of these paintings are in the Munch Museum Oslo, one in the Würth Collection in Künzelsau .

Munch also created two lithographs in 1895 , for the second version of which he worked out the color plates in 1902. Prints of the second version can be found in numerous museums, including Berlin, Bremen, Chemnitz, Essen, Frankfurt am Main, Hamburg, Salzburg, Stuttgart and Wuppertal.

Vampire . Lithograph, 1895, 38.5 × 54.8 cm, Thielska galleriet Stockholm

Vampire . Lithograph, 1895/1902, 38.5 × 54.8 cm, Thielska galleriet Stockholm

interpretation

vampirism

Vampire is not the original title of the image. The reference to vampirism was first established by Stanisław Przybyszewski , who interpreted in a treatise on Munch in 1894: "A broken man and a biting vampire face on his neck". Przybyszewski identified an "immeasurable fatality of resignation" in the attitude of the man who surrendered with joy to his impotence and lack of will. “He won't get rid of the vampire, he won't get rid of the pain, and the woman will always sit there and bite forever with a thousand snake tongues, with poisonous teeth.” August Strindberg interpreted the picture in a similar way in 1896: “Goldener Rain falls on the unfortunate man who kneels down to beg the grace of his worse self to be killed by pinpricks. Golden cords that bind to the earth and to suffering, rain of blood poured out in cascades over the madman who seeks misfortune, the divine misery of being loved, that is to say to love. "

Uwe M. Schneede pointed out that the interpretations of the two writers are based heavily on their own views that were widespread in the art world at the time. In Stanisław Przybyszewski's De profundis, for example, a sister appears to her incestuous brother as a vampire, and Strindberg refers to his plea of a madman . Munch accepted Przybyszewski's picture title, but wrote in 1933 that he gave the picture a “literary character. In reality it is only a woman who kisses a man on the neck ”. Instead of vampirism in the physical sense, the picture can therefore also be interpreted as an attempt by a woman to bind the man to her through her love, a subject that is often problematized in Munch's work. The stylistic devices used, the dark coloring, the color contrasts, the flat shapes, the towering shadows, however, contribute to lending the everyday scene an ominous, threatening, almost demonic aura.

Love and pain

Munch's original name for the motif was love and pain . According to Reinhold Heller, Munch has translated personal experiences and his “suffering in love” into a general form of expression that becomes a “symbol of the gender struggle” and an eroticism that is perceived as oppressive and demonic . Beate Elsen Schwedler sees the symbolic representation of "a dramatic man-woman relationship" in the image, which reveals both devotion and fear of losing control. The man crouches in a submissive posture in front of the dominantly embracing woman. Her strands of hair are reminiscent of tentacle arms and symbolize the equally promising and fatal attraction of female eros. As the characters merge, the feelings of love and pain or love and hate also merge.

Since the first exhibition under the title Study for a Series “Die Liebe” in December 1893 in Berlin, Vampire has been one of the pictures of the so-called Life Frieze , a compilation of the central works of Edvard Munch, to which he later subtitled “A poem about life, love, death ”bestowed. For Munch, all three topics are related and mutually dependent. Love comes in many shades and includes negative feelings such as jealousy and despair. Munch saw in her the strength that can overcome death and create new life. For him, the act of love also symbolized the encounter with death and eternity. Munch found the essential features of the relationship between man and woman united in love and pain . At the first presentation of the life frieze, he presented the picture as the motto of the exhibition.

Woman's hair as a symbol

In his work, Munch has repeatedly stylized long women's hair as a symbol of female power and strength and as a symbol of an energetic connection between the sexes. To a certain extent, it is a “template for the feminine par excellence” and stands for everything that is both attractive and fatal to Munch about the female gender. In the painting Detachment, for example, also part of the frieze of life, the hair is stretched as a visible band between a brightly clad woman looking out to sea and a turned away man who grabs his bleeding heart. Here, too, a man stands between love and pain, between a connection to a woman and a separation from her. A lithograph based on the same motif goes even further and lets the woman's hair grab a man's heart directly.

The motto of the female hair also applies to the lithograph male head in female hair. It wraps around the head of a man positioned below her in strands of red. Munch repeated the motif in 1903 with a double portrait of the English musician Eva Mudocci, his lover at the time, and himself. While the woman tilts her head to one side and smiles blissfully, the man, surrounded by her hair, shows a grouchy face. Munch named the picture Salomé after the play of the same name by Oscar Wilde , in which a woman has the head chopped off the man who turns her away. This title led to a falling out between Mudocci and the painter.

Pictorial history

According to Munch's memory, the first designs for Vampir go back to the time when he was working on The Sick Child , i.e. the years 1885/86. Reinhold Heller, however, dated the first drawings of the motif to the year 1890. At the same time, one of the entries in Munch's notebook was entitled intermezzo : “He was sitting with his arm around her body. Her head was so close to him. It was somehow so wonderful to feel her eyes, her mouth, her breasts so close to you [...] He buried his face in her lap. She bowed her head over him and he felt two warm, burning lips on the back of his neck. A shudder ran through his body, a shiver of lust. And he hugged her convulsively. "

Heller attributes Munch's original experience to his unhappy love for Milly Thaulow, the wife of his cousin Carl Thaulow. It is possible, however, that different women from the painter's environment were summarized in the "vampire woman". During the years in which the painting was made, Dagny Juel , Stanisław Przybyszewski's wife, had a particularly strong influence on the painter. Various art historians have identified her as a model for Madonna , a motivic counterpart to Vampire . Munch also worked on both motifs in parallel as prints.

Edvard Munch: Madonna . Oil on canvas, 1893, 90.5 × 70.5 cm, Norwegian National Gallery

From 1890 on, Munch worked on the subject in numerous drawings and watercolors . This also includes Young Man and Whore , a study in which Munch portrayed himself on the bosom of a Berlin prostitute. Another variant, the opposite of the vampire motif , can be found in the etching Trost from 1894. Here it is the man who comfortingly wraps his arms around a weeping woman with long hair.

Adolf Paul , a friend of the painter, remembered the first creation of the vampire painting . One day he visited Munch in his studio and found a woman with flaming red hair who had fallen onto her shoulder "like clotted blood". Munch asked his friend to kneel down in front of the woman: “She leaned over me and pressed her lips to my neck [...] her red hair flowed over me. Munch began to paint and within a short time he had finished the vampire. "

In February 1988, Norwegian art thief Pål Enger stole one of Vampir's frames from the Munch Museum in Oslo. He was also unmasked six years later as the head behind the theft of The Scream from the same museum, which caused a lot of public attention.

The image version from 1894, which had been privately owned since 1903, was auctioned by Sotheby’s in 2008 . It fetched $ 38 million and was Munch's most expensive painting at the time, before the record was broken by a version of The Scream in 2012 . At the time, a $ 1.5 million multi-color graphic of Vampire was the painter's most expensive graphic.

literature

- Carmen Sylvia Weber (ed.): Edvard Munch. Vampire. Readings on Edvard Munch's Vampire, a key image of the early modern age . Catalog for the Edvard Munch exhibition . Vampire , January 25, 2003 - January 6, 2004, Kunsthalle Würth , Schwäbisch Hall. Swiridoff, Künzelsau 2003, ISBN 3-934350-99-2 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Carmen Sylvia Weber (ed.): Edvard Munch. Vampire. Readings on Edvard Munch's Vampire, a key image of the early modern age , p. 21.

- ↑ Carmen Sylvia Weber (ed.): Edvard Munch. Vampire. Readings on Edvard Munch's Vampire, a key image of the early modern age , p. 31.

- ^ Gerd Woll: The Complete Graphic Works . Orfeus, Oslo 2012, ISBN 978-82-93140-12-2 , pp. 70-73.

- ↑ Quoted from: Carmen Sylvia Weber (ed.): Edvard Munch. Vampire. Readings on Edvard Munch's Vampire, a key image of the early modern age , pp. 23-25.

- ↑ Quoted from: Carmen Sylvia Weber (ed.): Edvard Munch. Vampire. Readings on Edvard Munch's Vampire, a key image of the early modern age , p. 25.

- ↑ Carmen Sylvia Weber (ed.): Edvard Munch. Vampire. Readings on Edvard Munch's Vampire, a key image of the early modern age , pp. 25–29, quotation p. 29.

- ↑ a b c d Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch. Life and work . Prestel, Munich 1993. ISBN 3-7913-1301-0 , p. 82.

- ↑ Reinhold Heller: Edvard Munch. Life and work . Prestel, Munich 1993. ISBN 3-7913-1301-0 , pp. 81-82.

- ↑ Carmen Sylvia Weber (ed.): Edvard Munch. Vampire. Readings on Edvard Munch's Vampire, a key image of the early modern age , pp. 7, 21–23, 29.

- ↑ Carmen Sylvia Weber (ed.): Edvard Munch. Vampire. Readings on Edvard Munch's Vampire, a key image of the early modern age , pp. 11–19.

- ↑ Carmen Sylvia Weber (ed.): Edvard Munch. Vampire. Readings on Edvard Munch's Vampire, a key image of the early modern age , pp. 21–23.

- ↑ Carmen Sylvia Weber (ed.): Edvard Munch. Vampire. Readings on Edvard Munch's Vampire, a key image of the early modern age , p. 23.

- ↑ Carmen Sylvia Weber (ed.): Edvard Munch. Vampire. Readings on Edvard Munch's Vampire, a key image of the early modern age , pp. 29, 37–39.

- ↑ Carmen Sylvia Weber (ed.): Edvard Munch. Vampire. Readings on Edvard Munch's Vampire, a key image of the early modern age , p. 27.

- ↑ Petra Bosetti: Woman with thirst for blood ( Memento of the original from January 5, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . In: art - the art magazine of September 24, 2008.

- ↑ See Pål Enger in the Norwegian Wikipedia on Bokmål .

- ^ Tom Bazley: Crimes of the Art World . Praeger, Santa Barbara 2010, ISBN 978-0-313-36047-3 , pp. 24-25.

- ^ Munch painting: "Vampire" appeared after 70 years . In: Der Spiegel from September 23, 2008.

- ↑ Peter Dittmar: An auction with a tangible hysterical factor . In: Die Welt from February 25, 2012.