The death in venice

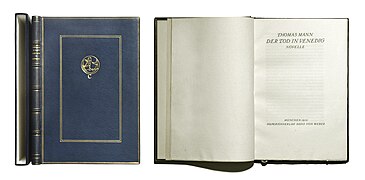

Death in Venice is a novella by Thomas Mann that was written in 1911. It was initially published as a special edition in an edition of 100 numbered copies signed by Thomas Mann, then in the Neue Rundschau and from 1913 as a single print by S. Fischer Verlag .

Thomas Mann called his novella the tragedy of humiliation: Gustav von Aschenbach, a famous writer of a little over 50 years and widowed for a long time, devoted his life entirely to achievement. A summer vacation trip takes him to Venice . There he observes a beautiful boy on the beach every day who lives with his elegant mother and sisters and their governess in the same hotel, the spa hotel . The aging man falls in love with him. He always maintains a shy distance from the boy, but the late intoxication to which the otherwise self-stubborn von Aschenbach now indulges himself willlessly turns him into an undignified old man.

content

First chapter

At the beginning of May 1911 (in the year of the second Moroccan crisis ) the 50-year-old writer Gustav von Aschenbach , who was ennobled for his works, took a walk through the English Garden in Munich, which led him to the “ Northern Cemetery ”. On the outside staircase to the funeral hall, he notices a strange man in hiking clothes, who looks at him “so warlike, so straight in the eye” that Aschenbach turns away. As you go on, the wandering continues to have an effect on the appearance of the stranger in Aschenbach. He became aware of a strange expansion of his inner being quite surprisingly, a kind of wandering restlessness, which he interprets as a desire to travel. He lets himself be challenged in breach of duty and thinks that a change would do him good, “a little impromptu existence, day-taking, distant air and supply of new blood”: Gustav von Aschenbach decides to travel.

second chapter

Aschenbach's origins, life and character are described, along with his works, their literary status and their appeal to the public. Aschenbach has long been widowed and lives alone. All his pursuit is directed towards fame. By no means of robust nature, he has to wrestle artistic achievements anew every day. With this self-discipline, investments from the father's side, mostly senior officials in Prussian Silesia, are realized. The maternal grandfather was a musician. This is where his artistic talent comes from.

third chapter

Aschenbach arrived on an island near the Istrian Adriatic coast , most recently by sea from Trieste via Pola . It's raining. The beach is disappointing, not "gentle and sandy", it does not convey a "calm, intimate relationship with the sea". Following a sudden inspiration, he travels by ship to Venice, which he visited several times as a young man. Inside the ship, a greasy purser handles him and praises his destination in phrase-like phrases. On deck he observes a brightly made-up old man who has joined a crowd of young men and tries to surpass them in terms of youthfulness by smoking and drinking too much and trying to attract attention with suggestive remarks. Once in Venice, Aschenbach wants to take the gondola to the vaporetto station. The monosyllabic gondolier, however, rows him across the lagoon to the Lido. Once there, Aschenbach leaves for a moment to change money to pay for the crossing. When he comes back, the gondolier is gone. From the helper with the boat hook, who is posted at the landing area, he learns that the man is the only gondolier who does not have a license.

In the evening von Aschenbach discovers a long-haired boy “perhaps fourteen years old” at the table of a Polish family in the hotel lobby, who appears to him as “completely beautiful”. He interprets his fascination as an aesthetic connoisseur, representing a conception of art that denies the sensuality of art. But with every day that Aschenbach observes and admires the young Tadzio on the beach, the aging man falls more and more into the sight of the young man.

The humid weather, the mixture of sea air and Scirocco do not get from Aschenbach. He remembers that in earlier years he had to flee Venice for health reasons. When he had sweat and fever attacks, he regretted having to leave the city this time as well and decided to travel to Trieste. At the train station, however, it turns out that his suitcase was accidentally sent to Como, a complication that Aschenbach uses as a welcome excuse to return to his hotel on the Lido to wait for his luggage to return. "Looking into himself" he realizes that it has become so difficult for him to say goodbye for Tadzio's sake. When his suitcase arrived two days later, he had long since discarded the idea of leaving.

Chapter Four

The otherwise so cool and sober Aschenbach gives himself completely to his feelings. The comparison with Socrates, who taught the young Phaedrus about the role of beauty, and the antiquated language of the novel describe the mythical transformation of the world in the eyes of Aschenbach. The chapter ends with his admission that he loves the boy.

Fifth chapter

A cholera epidemic from India has reached Venice. Several attempts to find out more about the disease from locals have failed. Even the diabolical leader of a small band of street musicians who appear outdoors and late at night in front of hotel guests does not give Aschenbach any information. The next day the employee of an English travel agency finally informed him about the cholera risk. Nevertheless, Aschenbach remains in the lagoon city. The one “haunted” by his late emotional intoxication rejects the idea of warning Tadzio's relatives about cholera in order not to have to do without its proximity.

Aschenbach has now lost all self-respect. To please, he has the hotel hairdresser dye and make-up his hair. He has thus arrived at the level of the dodgy old man, whose desired youthfulness he had to watch with reluctance on the way there. Infected by overripe strawberries that he bought while strolling through the streets of Venice, Aschenbach dies of cholera while watching Tadzio one last time on the beach from his deck chair. It seems to the dying as if the boy was smiling and waving to him from afar and pointing with the other hand out to sea. "And, as is so often the case, he set out to follow him."

shape

Thomas Mann himself called death in Venice in his abstract of life the "tragedy of degradation" and meant the term tragedy quite literally, because his novella shows several classicistic features:

- the division into five chapters analogous to the five acts of classical drama , including the

- Horatian five-part structure in exposure , complication, peripetia , retardation and catastrophe ;

- the mythological depth perspective of the action;

- the repeated recourse to Plato's dialogue Phaedrus ;

- the street musicians parodying the chorus of Greek tragedy, who at the same time addressed the

- Remember origin of theater in the cult of Dionysus, and

- the temporarily (fourth chapter) antiquing speech rhythm.

Artist problem

Thomas Mann describes the failure of an ascetic, exclusively performance-oriented life that has to get by without interpersonal support. Lonely, excluded from the happiness of carefree light-heartedness, hard working, Gustav von Aschenbach achieved fame and greatness with his literary work. Proud of his achievements, he is full of mistrust in his humanity and has no belief that he can be loved. A boy enters his life, whose androgynous grace becomes for Aschenbach the incarnation of perfect beauty. He justifies his fascination and passion for this ideal image with philosophical arguments by repeatedly referring to the Platonic dialogue between Socrates and Phaedrus in his daydreams and modifying and aesthetically reflecting it for his purposes: Beauty is "the only form of the spiritual that we receive sensually to be able to endure sensually. ”Only it is“ divine and visible at the same time, and so it is then the path of the senses ”and therefore“ the path of the artist to the spirit. But do you now, my dear friend, believe that someone can ever gain wisdom and true manly dignity for whom the path to the spiritual leads through the senses? "Like his self-critical author Thomas Mann, Aschenbach also sees the charlatanism of everything artistic:" You see now, that we poets cannot be wise nor worthy? That we must necessarily go astray, remain necessarily dissolute and adventurers of feeling? The mastery of our style is lies and foolishness, our fame and honor a farce, people's trust in us is ridiculous ”. And like the author, his protagonist also sees the questionable sides of the artist, who does not find death in Venice by chance, but rather knowingly seeks it: “From now on, our endeavors are only aimed at beauty; second impartiality and form. But form and impartiality, Phaedrus, lead to intoxication and desire, perhaps lead the noble to terrible emotional violence, which his own beautiful severity rejects as infamous, lead to the abyss, they too. They lead us poets there, I say, because we are unable to soar, we can only wander. "

Death motives

A central motif of the novella is the messenger of death, which appears in various forms:

- For the first time in the "des Stranger" in front of the cemetery hall. In the look duel that he leads with Aschenbach, Aschenbach is defeated and looks death in the eye , without even knowing it . Deceiving himself, he interprets the unrest and the “strange expansion of his inner being” as a desire to travel.

- The ghostly looking paymaster during the voyage to Venice is reminiscent of the boatman Charon , who, in the imagination of ancient Greece, translated the deceased into Hades and received an obolus as a ferryman's wages .

- The gondolier rowing Aschenbach across the lagoon and the cheeky singer and leader of a group of street musicians are also heralds of death. What all three have in common with the traveler in front of the funeral hall is that they are described as strangers, red-haired, beardless, thin, with a protruding Adam's apple, pale and stumpy. Their strangeness becomes more and more a characteristic of the Dionysian, especially in the guise of the guitarist and singer. In mythological research at the beginning of the twentieth century, Dionysus was still considered to be a deity originally foreign to Greece who had come to Greece from Asia Minor.

- The motif of the messenger of death culminates in the figure of the graceful Tadzio. In the final image of the novella, the dying man says that Tadzio is smiling at him and pointing from the seashore with his hand “into the monster full of promise”. This gesture turns Tadzio into a Hermes incarnation, because one of the tasks of this deity was to lead the souls of the deceased into the world of the dead.

Other death symbols:

First chapter:

- The name of the tragic hero. The combination of words subliminally associates the reader with “ashes in a stream” as a kind of burial. (P. 9 line 1)

- The cemetery entrance. (P. 10 line 13)

- The exhibits of the stonemason company that imitate an "unhoused grave field".

- Evening atmosphere. (P. 10 line 21)

- The scriptures above the entrance of the funeral hall, “You enter the dwelling of God” or “May the eternal light shine on you”. (P. 11 line 3)

- Adjectives such as B. the "apocalyptic" animals (p. 11, line 10)

- The physiognomy of the traveler in front of the funeral hall, the description of which suggests a skull.

Third chapter:

- The Venetian gondola, the blackness of a coffin, which lets its passengers "relax comfortably".

- The sea with its effect of the “indivisible, immoderate, eternal, nothing”. In Thomas Mann's metaphor , the sea is a symbol of death : "Because love for the sea is nothing else than love for death" he wrote in his 1922 essay Von Deutscher Republik . Tadzio watches von Aschenbach play every day on the beach, "and the sublime view of the sea has always been a foil and background to his appearance".

Fifth chapter:

- The pomegranate juice that Aschenbach finishes after the performance of the street musicians. The drink alludes to the Persephone myth: Anyone who has tasted the pomegranate of Hades can no longer return to the upper world, regardless of whether they are mortal or deity. Thomas Mann confirms the symbolism of death with the inner image of an hourglass , which he creates in this situation at von Aschenbach.

Mythological motifs

Von Aschenbach gives himself completely to the admiration of the boy. “That was the intoxication; and the aging artist greedily welcomed him ”. In the manner of Plato's dialogues, “the enthusiastic” imagines conversations with the admired. In them he breaks with his Apollonian , disciplined view of life. "[...] because passion, like crime, does not conform to the assured order and welfare of everyday life." He recognizes the sensuality of art and monologues: "[...] you must know that we poets do not take the path of beauty can go without Eros joining in and posing as the Führer. ”But with that, von Aschenbach glossed over. It is not Eros who guides him. It is Dionysus to whom he fell. Robbed by him of his clear Apollonian worldview, von Aschenbach thinks that the artist is “born with an incorrigible and natural direction towards the abyss”.

Von Aschenbach's degeneration finds a wild climax in the dream of the fifth chapter. He comes under the rampant revelers of an ancient Dionysus cult. “But with them, in them the dreaming now belonged to the strange god. Yes, they were himself when they threw themselves tearing and murdering on the [sacrificial] animals and devoured steaming scraps, when boundless intermingling began on the churned moss ground, sacrificed to God. And his soul cost the fornication and frenzy of doom. "

Other mythological allusions:

- The stranger in front of the entrance to the funeral hall, standing elevated on the outside staircase, is more than a marginal figure. It is also an allegory . This is how it appears: It remains to be seen where it has just come from, and it has disappeared again just as without a trace. Mythologically, he can be understood as both Thanatos and Dionysus [motif of well-traveled and foreignness]. Finally, his posture with the crossed feet is reminiscent of a typical pose of ancient Hermes sculptures.

- The gondolier does not row from Aschenbach to the vaporetto station, but against his will across the lagoon to the Lido. After comparing the gondola with a coffin, the reader has a Charon association. The last crossing is also without turning and the ferryman determines the destination.

- The fourth chapter begins with mythological images from ancient Greece, in a hymnic language and a syllable rhythm from which one or the other hexameter can be read. It could be overwritten with “mythical transfiguration of the world”.

- Tadzio is "the tool of a derisive deity", the intoxicating and unrestrained god Dionysus . At the same time, however, he is also Hermes Psychopompos , who ultimately led Aschenbach into death or the sea.

Decadence motifs

In literary history, Death in Venice , written on the eve of the First World War , is both the climax and the end of the decadence literature of the late 19th century. The Zauberberg (1924) is no longer one of them. It forms the transition to the second half of his life's work. In the sanatorium novel, Thomas Mann says goodbye to “sympathy with death”.

- Venice itself, with its "faintly putrid smell of sea and swamp", is one of the central symbols of decadence in the literature of the time. Venice is also the city where the man admired Richard Wagner found his musical inspiration for Tristan and Isolde - and where Wagner died, a death in Venice.

- Aschenbach does not get the climate of Venice. During the attempt to leave (chapter three), he recognizes the city “as an impossible and forbidden stay for him, which he was unable to cope with.” Aschenbach's impotence finally leads to a wish to die. He knew from an employee of an English travel agency that Indian cholera was rampant in the city, that a green goods dealer had recently died of the disease, "probably food had been infected, vegetables, meat or milk". German daily papers had also reported on "the visitation of the lagoon city". Nonetheless, he buys “some fruit, strawberries, overripe and soft goods” in front of a small vegetable shop “in the sick town” and ate away while walking ”.

- As a child, Aschenbach had a weak constitution and had been excluded from school on medical advice. Heads of house had to teach him. He has to wrestle his achievements as a writer with the greatest strain of will, constantly on the verge of exhaustion. Aschenbach finds his heroism and ethos in the daily overcoming of weakness. Since his love for Tadzio is a reaction to what has been repressed so far, perversion emerges from it. “Paradoxically, this is how aesthetics produce the unaesthetic, the false cult of the beautiful the ugly and distorted. 'Breeding' leads to fornication. This is the path of the once 'exemplary' writer Aschenbach, who even achieved the honor of the school books - the tragedy of the uncreative man of decadence. "

- Tadzio's pale complexion looks sickly. Aschenbach later noticed Tadzio's unhealthy teeth - with Thomas Mann always a sign of decadence and decay. Aschenbach does not believe that the boy will one day grow old and feels a "feeling of reassurance or satisfaction" at this statement.

- The aging artist Aschenbach has reached the critical threshold “where the power of repression and discipline goes out. This age crisis is more than individual. It represents the age crisis of the sterile bourgeois culture of the 19th century, which passes from the stage of decadence, which is convulsively concealed by bourgeois 'morals', into the open. "

Self-comments by Thomas Mann

On July 4th, 1920 Thomas Mann wrote to the poet and essayist Carl Maria Weber (1890–1953): “Passion as confusion and degradation was actually the subject of my fable - what I originally wanted to tell was nothing homo-erotic at all, it was the - grotesquely seen - story of the old man Goethe about that little girl in Marienbad whom he wanted to marry with the consent of the nerdy-matchmaker mom and against the horror of his own family, this story with all its horribly comical situations that inspire awe-inspiring laughter, […]. “The title of the plan of the novella was: Goethe in Marienbad .

“A balance between sensuality and morality was sought [...]. But you cannot have missed the fact that the novella is of hymnal origin. ”Thomas Mann also quotes a sequence of seven hexameters from his Gesang vom Kindchen, which refers to the Venedignovelle. The sequence concludes: “See, the drunken song became a moral fable for you.” For the sake of modernity, he felt compelled to “see the 'fall' pathologically and this motif (climacteric) with the symbolic (Tadzio as Hermes Psychopompos ). ”“ Something even more spiritual, because more personal, was added: the not only 'Greek', but Protestant-Puritan ('bourgeois') basic constitution of the experiencing heroes not only, but also myself; in other words: our thoroughly suspicious, thoroughly pessimistic relationship to passion itself and in general. "

Biographical references

The story has several parallels to the author's biography:

- Numerous incidents in the novella go back to the Mann family's trip to Venice in 1911, which Katia Mann reported in “My Unwritten Memoirs”.

- The possible encounter with the young Polish baron Władysław Moes (1900–1986) during his stay in 1911 is said to have given the impetus for Death in Venice . He claimed in 1965 in the magazine twen (Munich): I was Thomas Mann's Tadzio . He suspected this mainly because of his Polish origins and the nickname Adzio , which he is said to have worn as a child. More recent research results doubt this assumption, in particular because of the lack of further suitable points of reference or contradictions.

- The works of the protagonist Gustav von Aschenbach, which are presented in the second chapter, are identical to Thomas Mann's already completed or planned works, even if their titles have been slightly alienated for the novella.

- In his essay on Adelbert von Chamisso , which was written in 1911 while working on Death in Venice , Thomas Mann pointed out the secret identity of the author and fabulous hero: “It's the old, good story: Werther shot himself, but Goethe stayed alive. "

- “This is a strange moral self-chastisement by a book.” With this autobiographical remark, Thomas Mann comments on his Venice novella in “Lebensabriß” (1930).

After Tonio Kröger , whom he called “a kind of self-portrait”, Thomas Mann sought to end the life style of the artist and poet, whom he “always faced with the utmost distrust” - as retrospectively in the autobiographical sketch Im Spiegel (1907). He gave himself a "constitution" and married the millionaire daughter Katia Pringsheim. At the time of the advertisement for Katia Pringsheim he wrote to his brother: “I am not afraid of wealth.” Heinrich Mann did not come to the wedding. He has sied Katia Mann all his life.

Thomas Mann prescribed the marriage as “a strict happiness” - not without skepticism: “Anyone who planned a“ Friedrich ”before“ Your Royal Highness ”,“ “probably never really believed in a 'strict marital happiness'”. With the novel Royal Highness (1909), which was written during the first few years of marriage , Thomas Mann initially did not regain the height of his writing abilities. But the death in Venice was a masterpiece. "Once everything is right, it comes together and the crystal is pure." Thomas Mann let "Gustav von Aschenbach" die on his behalf and accepted himself from then on. He let go of the life lie of "strict marital happiness".

For Katia Mann, who had recognized her husband's homoerotic orientation in the Venice novella, a long period of sickness and various stays in sanatoriums followed, the most famous of which was in Davos. Thomas Mann found the inspiration for Der Zauberberg in Davos when he spent a few weeks there on a visit. After the death in Venice , after giving up the effort of will to live a "strict marital happiness", it was from now on deep gratitude that bound him to his wife Katia and which should prove to be very sustainable.

Edits

In 1971 the novella was filmed by the Italian director Luchino Visconti under the title Morte a Venezia (German: Death in Venice ) with Dirk Bogarde as Aschenbach.

In 1973 Benjamin Britten's opera Death in Venice premiered at the Aldeburgh Festival .

John Neumeier choreographed and staged the ballet Death in Venice, which he called the "Dance of Death , loosely based on Thomas Mann". He used works by Johann Sebastian Bach on the one hand , mainly the Musical Sacrifice , and on the other hand various compositions by Richard Wagner , including the prelude and Isolde's love death from Tristan and Isolde . The world premiere took place on December 7, 2003 in Hamburg. The Hamburg Ballet danced . Aschenbach, who is a choreographer in this version, was danced by Lloyd Riggins , Tadzio by Edvin Revazov.

literature

Text output

- Thomas Mann: Death in Venice. S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1992, ISBN 3-596-11266-4 , 139 pp.

- Thomas Mann: Death in Venice. (Special edition). S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2007, ISBN 978-3-596-17549-9 , 139 pages

Secondary literature

- Gilbert Adair: The Real Tadzio: Thomas Mann's 'Death in Venice' and the Boy Who Inspired It . 2001. Carroll & Graf. (German translation: Adzio and Tadzio. 2002. Edition Epoca.) (To Władysław Moes)

- Ehrhard Bahr: "Death in Venice", explanations and documents . Reclam, Stuttgart 1991.

- Andreas Blödorn: “Who looked at death with eyes” - fantastic things in “Death in Venice”? In: Thomas Mann Jahrbuch 24 (2011), pp. 57–72.

- Ernst Braches: Commentary on Death in Venice . De Buitenkant, Amsterdam 2016, ISBN 978-94-90913-56-4 .

- Manfred Dierks: Studies on myth and psychology with Thomas Mann. Studies on "Death in Venice", the "Magic Mountain" and the "Joseph Tetralogy" based on his estate . In: Thomas Mann Studies , 2nd vol. Bern 1972.

- Werner Frizen: Death in Venice (Oldenbourg interpretations No. 61). Munich 1993, ISBN 3-486-88660-6 .

- Guido Fuchs (ed.): Tadzios Brothers. The “beautiful boy” in literature , Monika Fuchs, Hildesheim 2015, ISBN 978-3-940078-42-1 .

- Ursula Geitner: Men, women and Dionysus around 1900: Aschenbach's dilemma . In: Kritische Ausgabe 1/2005, 4ff. ISSN 1617-1357 .

- Wilhelm Große, explanations on Thomas Mann: Death in Venice , text analysis and interpretation (vol. 47). C. Bange Verlag , Hollfeld 2012, ISBN 978-3-8044-1987-2

- Martina Hoffmann: Thomas Mann's Death in Venice. A history of development in the mirror of philosophical conceptions . Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1995, ISBN 3-631-48782-7 .

- Tobias Kurwinkel: Apollonian outsiders. Configurations of Thomas Mann's "basic motif" in narrative texts and film adaptations of the early work. With an unpublished letter from Golo Mann about the making of the film adaptation “Der kleine Herr Friedemann”. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2012, ISBN 978-3-8260-4624-7

- Hans Mayer : Thomas Mann . Frankfurt am Main, Suhrkamp 1980, ISBN 3-518-03633-5 .

- Hans W. Nicklas: Thomas Mann's novella "Death in Venice". Analysis of the motivational context and the narrative structure . In: Josef Kunz, Ludwig Erich Schmitt (Ed.): Marburg Contributions to German Studies , Vol. 21. Marburg 1968

- Holger Pils, Kerstin Klein: Lust of Doom - 100 Years of Thomas Mann's “Death in Venice”. Wallstein, Göttingen 2012, ISBN 978-3-8353-1069-8 .

- Thomas Spokesman (Ed.): Love and Death - in Venice and elsewhere. The Davos Literature Days 2004 . Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 2005, ISBN 978-3-465-03438-4 .

- Hans Wysling , M. Fischer (ed.): Poets about their poems. Thomas Mann. [Without specifying the place of publication] Ernst Heimeran Verlag 1975, pp. 393–449.

- Hans Wysling: Documents and Investigations. Contributions to Thomas Mann research . Bern 1974.

- Hans Wysling, Yvonne Schmidlin: Thomas Mann. A life in pictures . Artemis, Zurich 1994, pp. 198–203.

The Wikipedia article Death in Venice is included in the bibliography of Thomas Mann Readers and Researchers at the Free University of Berlin .

Web links

- Death in Venice in Project Gutenberg ( currently not usually available for users from Germany )

- Eva D. Becker: Thomas-Mann-Figurlexikon in the portal Literaturlexikon online

- Lust of doom - 100 years of Thomas Mann's “Death in Venice” . For the exhibition in the Buddenbrookhaus Lübeck

References and comments

- ↑ Issue 10-11

- ↑ On Thomas Mann's motif of the "Visitation" see also Der kleine Herr Friedemann .

- ↑ Thomas Mann fails to expressly name the cause of death. But a few pages earlier, speaking about cholera in general, he mentions the possibility of such a sudden, fatal outcome.

- ↑ Loneliness in this context alludes to Schopenhauer's thoughts on spirituality and "intellectual aristocracy".

- ↑ Abridged and adapted rendition of an early, as yet undetermined character draft from Das Theater als Tempel .

- ↑ Compare with this "Dionysian intoxication" also the section Mythological motifs (see below).

- ↑ Beardlessness was unusual in the face of men's fashion before the First World War.

- ↑ See Mann's commentary in his letter of March 29, 1949 to Hermann Ebers.

- ↑ See the chapter on snow ( Hans Castorp's snow dream ).

- ↑ Werner Vordtriede: Richard Wagner's death in Venice . In: Euphorion , 52, 1958, pp. 378-395.

- ↑ Apart from the current risk of infection, von Aschenbach has given himself up to the point that he eats from a bag while walking in public - a blatant indignity for a "gentleman" before the First World War. A “gentleman”, when he was strolling, went with a hat, walking stick and gloves that were carried in hand in summer.

- ↑ Jochen Schmidt: Thomas Mann: Decadence and Genius. In: Jochen Schmidt: The history of the genius thought in German literature, philosophy and politics 1750-1945. Volume 2, Darmstadt 1985, p. 252.

- ↑ Jochen Schmidt: The history of the genius thought in German literature, philosophy and politics 1750-1945. Volume 2, Darmstadt 1985, p. 247 f.

- ↑ Hans Joachim Sandberg: The "strange god" and cholera. Gleanings on death in Venice . In: Eckhard Heftrich, Helmut Koopmann (ed.): Thomas Mann and his sources: Festschrift for Hans Wysling . Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 1991, p. 78.

- ↑ Hermann Kurzke: Thomas Mann. Special edition: Life as a work of art. A biography . C. H. Beck, Munich 2006, p. 194.

- ↑ A portrait of the boy contains: H. Wysling, Y. Schmidlin (ed.): Thomas Mann. A life in pictures .

- ↑ Volker Hage: Tadzio's beautiful secret . In: Der Spiegel . No. 52 , 2002, p. 152 ff . ( online - December 21, 2002 ).

- ^ Thomas Mann on January 26, 1903 to Richard von Schaukal

- ↑ On January 17, 1906 to Heinrich Mann: “You are absolute. I, on the other hand, deigned to give myself a constitution. "

- ^ To Heinrich Mann on February 27, 1904

- ↑ Katia Mann: My unwritten memoirs

- ^ A larger novella about Friedrich II.

- ^ On January 26, 1910 to Heinrich Mann

- ^ On March 12, 1913 to Philipp Witkop

- ↑ Jochen Eigler: Thomas Mann - Doctors of the family and medicine in Munich. Traces in life and work (1894–1925). In: Thomas spokesman: Literature and illness in the fin-de-siecle (1890–1914): Thomas Mann in a European context: the Davos Literature Days 2000 . Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 2002, p. 13 ff.

- ↑ See overall: Ruprecht Wimmer: Opening of the Davos Literature Days 2004. Love and Death. In Venice and elsewhere . In: Thomas spokesman: Love and death - in Venice and elsewhere . Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 2005, p. 9 ff.