Wang Mang

Wáng Mǎng ( Chinese 王莽 , IPA ( standard Chinese) [ u̯ɑŋ35 mɑŋ214 ]; * 45 BC ; † October 6, 23 AD ) was Emperor of China from 9 AD to 23 AD . He came from an influential aristocratic family and made a career at court with the help of his relatives. Wáng Mǎng was always modest and knew how to win over public opinion. Among several child emperors he was the gray eminence behind the throne until he finally ascended it himself. As a ruler, he acted rather unsuccessfully. He angered China's neighbors, failed to curb administrative corruption, and eventually fell victim to a riot. His successor founded the Eastern Han Dynasty . The most important source for the reign of Wáng Mǎng is the Han Shu .

Life

Origin and advancement

Wáng Mǎng came from a powerful and influential noble family during the Han Dynasty . Emperor Yuandi (ruled 48–33 BC) had made his concubine from the Wáng family, Wáng Zhengjun, empress. Wáng Mǎng's father Wáng Mǎn was the younger brother of the Empress. This brought her brothers and her nephew to high offices. Wáng Mǎn died before his sister's son took office. His son Mǎng could therefore not afford the luxurious lifestyle of his cousins, despite his close relationship to the imperial family. He made a virtue of necessity and wore the modest clothing of a Confucius student .

In addition to his humility and studies, Wáng Mǎng also made a name for himself through his care for his family. After the death of his brother Wáng Yong, he took care of his son Wáng Guang and looked after his uncle, the powerful General Wáng Feng, when he was 22 BC. Became seriously ill. Feng was deeply touched by the sympathy of his nephew, who watched his sick bed day and night, and stood up for him with the Empress Mother and Emperor Cheng . After the death of his uncle, Wáng Mǎng received a post at court and was later appointed deputy commander of the imperial guard.

The year 16 BC BC brought another rise for Wáng Mǎng. Margrave Wáng Shang, another uncle of the aspiring courtier, asked the emperor to transfer part of the Margraviate of Chengdu under his control to his nephew. Since a number of influential courtiers voted in favor of the proposal, Emperor Cheng not only granted the margrave's request, but also appointed Wáng Mǎng minister without a portfolio. The newly appointed minister, who evidently had earned an excellent reputation at the imperial court, continued to be very modest and supported schoolchildren and students instead of amassing wealth himself. Wáng Mǎng's modesty was also evident in the private sphere. He had only one wife and, unlike many nobles of his time, did not have concubines .

Commander in chief

In the meantime, Wáng Gen, also an uncle of Wáng Mǎng, had become, like his brother Feng, commander-in-chief of the imperial army before him. His nephew, along with Chunyu Zhang, was one of the hottest contenders for Gen's successor. Chunyu benefited from his good relationship with the empress, while Wáng Mǎng could only refer to his relationship with the empress mother. In order to secure the influential post nevertheless, he looked for incriminating material against his rival. In fact, he was able to prove that Chunyu had accepted bribes from an outcast wife of the emperor and also planned to secure posts at court for numerous supporters if he were to succeed Wáng Gen.

In the year 8 BC Wáng Mǎng presented his evidence to the emperor and the empress mother. They were not pleased with Chungyu's behavior and sent him into exile. Chungyu initially complied with the verdict, but instructed his cousin Wáng Rong to campaign for his stay in the capital. He left his horses and wagons to Wáng Rong. When the bribed attempted to intervene with the emperor in Chungyu's favor, he became suspicious and had Wáng Rong arrested. When the prisoner committed suicide on the advice of his father, the suspicious Emperor had Chungyu questioned again. The latter now admitted to having taken money from the former empress and was executed. When the poor health Wáng Gen announced his resignation a little later, the 37-year-old Wáng Mǎng became commander in chief of the imperial armed forces.

Even after receiving the highest honors, Wáng Mǎng remained humble and worried more about talented students from poor families than about his own well-being. Gradually, he was able to revise the bad image many Chinese had of his family. Even as after the sudden death of Emperor Chen 7 BC. His nephew Ai ascended the throne, Wáng Mǎng remained commander in chief. However, when a power struggle broke out between the young emperor's grandmothers, his aunt Wáng Zhengjun urged him to resign. Ai initially rejected Wáng Mǎng's resignation. However, the latter incurred the anger of Fu, the other grandmother of the emperor, when he tried to assign her a worse place at a banquet, and resigned as commander in chief to appease Fu.

Return to power

Wáng Mǎng initially stayed in Chang'an and continued to act as the emperor's advisor. However, when the Prime Minister and his deputy spoke out in favor of punishing him for his misconduct towards Fu, he was forced to 5 per cent. Left the capital. He settled in his margraviate, where he led a secluded life in order not to raise suspicions that he was secretly planning a rebellion. In the meantime, several hundred petitions were received at the imperial court demanding his return to Chang'an. Emperor Ai finally corresponded to 2 BC. This request. Wáng Mǎng was allowed to return to the capital, but was not given an official post. This only changed after Ai's death the following year.

After the relatives of Empress Fu had previously determined politics, Wáng Zhengjun now took the initiative. She enthroned the last male descendant of her husband under the name Pingdi and reappointed her nephew as commander in chief. Wáng Mǎng took over the reign of the minor Pingdi and took a number of drastic measures to secure his position: Fu's relatives were deposed and banished, Fu himself and the late Emperor Cheng's wife were suicided, and their followers lost their posts. Fu lost their titles posthumously, and her relative Dong Xian was exhumed and reburied in a prison.

After he had consolidated his power, Wáng Mǎng set about systematically expanding the cult around himself. He had prophecies spread that he was the reincarnation of mythical rulers like the legendary Ji Dan . He also changed the names of government institutions and some places and replaced them with names reminiscent of the Zhou or the Shang dynasties. From Vietnam he had an albino chicken sent to the court in 1 AD. Since these rare animals were regarded as a sign of divine favor, he was able to convince his aunt to give him even more powers. In the meantime, however, he did not forget to keep the emperor's relatives away from the court and to curtail their influence.

father and son

Still, Wáng Mǎng could not be sure of his cause. To make his position unassailable, he decided to marry his daughter to Emperor Pingdi. However, he did not want to jeopardize his reputation as a humble man and therefore pretended to ask his aunt Wáng Zhengjun not to consider his daughter as a wife. At the same time he organized a series of letters of petition in which his subjects assured the emperor to marry the regent's daughter. His plan was successful, and in AD 4 Pingdi married Wáng Mǎng's daughter and made her empress. Now, however, he was threatened with danger from his own family: his son Yu had sided with his enemies and, with the help of his teacher, tried to overthrow his father.

Wáng Yu had initially tried to bring the mother of the late Emperor Ai back to court. When his father stayed tough, he resorted to staging seemingly supernatural events and thereby discrediting his father. He asked his brother-in-law to smash a bottle of blood on the regent's door to indicate his cruelty. However, Yu's brother-in-law was discovered by the guards. Wáng Mǎng had everyone involved in the conspiracy executed, but had them tortured beforehand in order to obtain the names of other co-conspirators. The bloody wave of purges that followed also fell victim to numerous government officials and some relatives classified as unreliable.

Only one person could be dangerous to Wáng Mǎng: the adolescent emperor, who had become more and more estranged from his regent. Pingdi was no longer willing to stand idly by as members of his family were banished or even killed. When Wáng Mǎng found out, he reacted quickly and ruthlessly. Towards the end of AD 5, he had the emperor's wine poisoned. Even in the event that Pindgi survived the poisoning, he had taken precautions and secretly wrote a prayer in which he offered the gods to sacrifice his life for that of his master. This prayer should serve as proof of his innocence. However, the precautionary measure proved unnecessary: Emperor Pingdi died a few days later without leaving an heir.

Accession to the throne

Since the descendants of Pingdi's grandfather had all died in the meantime, a successor to the murdered emperor was now sought among those of his great-grandfather. Wáng Mǎng was now looking again for an underage heir who was not yet able to exercise government affairs and was therefore dependent on him. In the meantime he led the official business as the "ruling emperor". Finally, in 6 AD, a two-year-old child was made crown prince, but not crowned emperor. Wáng Mǎng, who continued to hold the title of reigning emperor, was able to successfully suppress several rebellions and decided in 9 AD to ascend the throne himself. He had a prophecy made depicting him as the divine heir of the first Han emperor, Gaozu .

Thanks to the fake prophecy, Wáng Mǎng was recognized as the emperor of China. He founded a new dynasty, the Xin Dynasty , and wanted to start a new golden age with his government. To this end, he brought the institutions of the empire and their names closer and closer to those of the Zhou dynasty, whose time was already mythically transfigured. In particular, Wáng Mǎng wanted to legitimize himself through urgently needed reforms based on the old model. He intended to distribute the fertile land more fairly by expropriating the large estates of the rich families and dividing them among the poor peasants. He didn't succeed. The officials, who were mostly landowners themselves, undermined his plan. After just three years, he had to take back most of his measures.

Only one of his innovations, the introduction of an income tax , which supplemented the previous system of poll tax and property tax , turned out to be forward-looking . It was one tenth of the profits made. Wáng Mǎng also hoped that the state revenue would be increased by monopolizing the trade in alcoholic beverages made from fermented rice and weapons. However, an extension of these monopolies to salt, iron, coinage, wood and fishing in 17 AD did not bring the desired income, as rampant corruption swallowed up large sums of money. Although the tax burden on the population increased, Emperor Wáng Mǎng actually had hardly any money left.

Foreign policy problems

The new emperor also wanted his power to be respected in terms of foreign policy. He made it clear to the Xiongnu , who lived north of his realm , that he regarded them as vassals, and by no means as equal partners. The Xiongnu, however, refused to submit to Wáng Mfenng and instead made preparations for war. The indignant emperor declared war on them. Contrary to the advice of his generals, he did not attack immediately, but waited until an army of 300,000 men had assembled with which he wanted to impress his enemies. He planned to break the power of the Xiongnu Khan by dividing his empire among his relatives. When Chinese troops kidnapped the Khan's brother and two sons for this purpose, he devastated northern China. The situation only eased with the death of the Khan in AD 14.

The south-western border of the empire remained uneasy. Wáng Mǎng had insulted the tribal chiefs there by depriving them of the title of prince conferred by the Han emperors and ordered the murder of the ruler of Juting , who refused to accept this demotion. The ruler's brother repeatedly undertook campaigns on Chinese territory, which even the generals posted there in 16 AD could not effectively prevent. The Koreans also repeatedly threatened the borders of the empire. The fact that Wáng Mǎng mocked their leader by twisting his name particularly angered the Koreans and made them repeatedly attack the northeastern border of China.

At the same time, relations with the Xiyu empires also deteriorated, as they were no longer willing to pay for the emperor's expensive delegations. Wáng Mǎng's Xiyu agent, Dan Qin, then had Xuzhili, the king of one of these kingdoms, called and executed. The executed man's brother fled to the Xiongnu and attacked Dan with their help, but was repulsed. The Xiyu realms now combined their forces and killed the imperial commissioner. A punitive expedition initiated by Wáng Mǎngs in AD 16 failed due to insufficient organization. One army was completely wiped out, another's way back to China was cut off.

Domestic political crises

Wáng Mǎng was so convinced that the government apparatus would function optimally as soon as it conformed to that of the Zhou that he culpably neglected its actual condition. While the emperor and his inner circle searched through sagas and legends for clues about the Zhou government, important decisions remained undone. The provincial governors, left to their own devices, filled their pockets in the meantime. The fact that a reform of the salary system initiated by the emperor, like so many other things, was not completed and many civil servants therefore remained unpaid, encouraged their self-service mentality. While Wáng Mǎng brooded over his reforms, the population groaned under the burden of bribes demanded. But it only became critical when the Yellow River burst its banks twice (3 AD and 11 AD) and led to devastating population losses in the most densely populated and most productive area of the empire. Starving farmers quickly found themselves in ever larger groups, which soon also worried the neighboring regions.

Nevertheless, the decisive families stood by the emperor. It was only when there was still no improvement in sight in AD 17 that there were occasional peasant revolts. The emperor sent negotiators to the rebels who, on their return, convinced him that he was dealing with incorrigible opponents of his policy. Wáng Mǎng ignored moderate voices and decided to put down the riots by force. This decision was to take bitter revenge. First, however, the emperor had to address family problems. His wife died in AD 21, his son Lin committed suicide when his father discovered he was having an affair with a lady-in-waiting, and shortly afterwards his second son An also died. Wáng Mǎng now confessed to two illegitimate sons and elevated them to dukes. His rule was now seriously threatened by the Lülin rebels united under Liu Yan .

A year later, the emperor had to realize that he had underestimated the peasant revolts. He had the rebels attacked by two of his best generals, who were initially able to achieve considerable success. When he denied the victorious troops the necessary rest, they suffered a crushing defeat by the rebels. Now the situation for Wáng Mǎng was slowly becoming critical. An epidemic that raged among the insurgents only gave him a short respite. The red eyebrow uprising now received support from three relatives of the disempowered Han dynasty. Because of their rich land holdings, they had their own troops with which they came to the aid of the rebels.

Defeat and death

Wáng Mǎng was no longer able to cope with the uprising. At the beginning of the year 23 AD, the combined troops of rebels and Han descendants defeated the imperial army in Nanyang . Liú Xuán , a distant relative of the Han dynasty, now assumed the imperial title. Wáng Mǎng threw all his remaining troops against the self-proclaimed emperor, a total of around 430,000 men. However, the followers of Liús, who took the name Gengshi as emperor, prevented Wáng's army from gathering and cut down the still separate parts of the army one by one. The defeat of the reigning emperor was now only a matter of weeks.

Gengshi now let his soldiers march to Chang'an. More and more volunteers joined them along the way, while their opponent's army had completely collapsed. On October 6, 23 AD, two Han generals finally conquered the capital Chang'an. Wáng Mǎng fell while storming his palace. His daughter, the former empress, also died. Wáng Mǎng's body was dismembered and his head was sent to the victorious Gengshi. The head was supposed to be shown on the city wall of its provisional capital Wancheng , but was removed again when angry subjects had cut out the dead man's tongue. However, it was kept in the imperial treasure for several centuries.

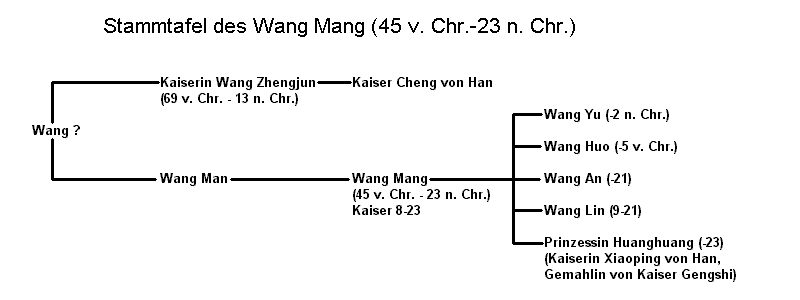

family

- Father: Wáng Mǎn ( 王曼 ), the brother of Empress Wang Zhengjun who died young

- Mother: Qu ( 渠 )

- Wives:

- Important concubines :

- Zhenzhi (增 秩), originally a servant with an unknown family name, mother of Wang Kuang

- Huaineng (懷 能), originally a servant with an unknown family name, mother of Wang Xin and a daughter

- Kaiming (開明), originally a maid with an unknown family name, mother of Wang Jie

- children

- Wang Yu (王宇) († 2)

- Wang Huo (王 獲) († 5 BC)

- Wang An (王安), Lord of Xinjia (9), later Prince of Xinqian (20; † 21)

- Wang Lin (王 臨), the Crown Prince (9), later Prince of Tongyiyang (20) (* 9 BC; † 21)

- Wang Xin (王興), Duke of Gongxiu (功 修; 21)

- Wang Kuang (王匡), Duke of Gongjian (功 建; 21)

- Princess Huanghuang (Empress Xiaoping of Han, appointed 10), originally Princess Mother of Ding'an (9; † 23)

- Wang Jie (王 捷), mistress of Mudai (21)

- a daughter (whose name cannot be correctly represented in Unicode ), mistress of Muxiu (21)

swell

The most important source for the reign of Wáng Mǎng is the historical work Han Shu . It was written by Ban Biao , Ban Gu, and Ban Zhao between 36 AD and 110 AD and covers the period from the beginning of the Western Han Dynasty to the usurpation of Wáng Mǎng. Since the Han Shu was written under the Eastern Han Dynasty , which overthrew Wáng Mǎng, it may portray him too negatively.

- Ban Gu: The monograph on Wang Mang . Edited by Hans OH Stange (= treatises for the customer of the Orient . Volume 23.3 ). Kraus, Nendeln 1966 (reprint of the Leipzig 1939 edition).

literature

- Hans Bielenstein : The Restoration of the Han Dynasty. With Prolegomena on the Historiography of the Hou Han Shu . In: Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities . tape 26 , 1954, pp. 1-209 .

- Helfried Ehrend: The coins of Wang Mang. A catalog (= Speyer numismatic contributions . Volume 14 ). Self-published, Speyer 1998.

- Rudi Thomsen: Ambition and Confucianism. A Biography of Wang Mang . Aarhus University Press, Aarhus 1988, ISBN 87-7288-155-0 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Wang Mang in the catalog of the German National Library

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Ruzi Ying from Han |

Emperor of China 9–23 |

Gengshi from Han |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Wang Mang |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Wáng Mǎng |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Emperor of China |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 45 BC Chr. |

| DATE OF DEATH | October 6th 23 |