Forced collectivization in the Soviet Union

The forced collectivization in the Soviet Union took place between 1929 and 1933, in the course of which a large part of the farmers were forced to give up their individual farms and join large socialist farms. By 1931 half of the farmers had been incorporated, by 1936 almost all of them. The measures had to be implemented against great resistance among the peasants. Many farmers slaughtered their cattle in order to prevent them from being expropriated, and some also destroyed their agricultural equipment. In order to enforce the forced collectivization, millions of farmers were resettled in barren regions or deported to forced labor camps ( deculakization ). As a result, the potential of agricultural production initially fell. Although food production declined, the Soviet leadership had large quantities of food requisitioned to sell on the world market in order to raise capital for industrialization . The measures caused a great famine in 1932/33 which, according to various estimates, killed 5 to 9 million people. The experience of the Holodomor led to strong independence movements in Ukraine . Ultimately it was possible to integrate the peasants into the communist state economy and to promote industrialization, whereby the forced collectivization did much more economic damage than good.

Development of the first 5-year plan

On the economic policy agenda of the state leadership, the increase in production, the industrialization of the Soviet Union and the constant expansion of the communist economic sector while suppressing the private sector were right at the top of the agenda. At the CPSU party congress in December 1927, the left-wing party demanded a maximum transfer of means of production and capital from the agricultural sector to industry, but could not (yet) assert themselves because the government initially shied away from conflict with the peasants. The State Planning Commission ( Gosplan ) was commissioned to draw up the first five-year plan valid from October 1, 1928 to October 1, 1933 . In the Gosplan, careerists who were particularly loyal to the regime soon ran into a race for the fastest route to socialism. Facts and reality were only marginally perceived. It is true that the Marxist economist Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin warned that agriculture should not be neglected in the course of industrialization. “The crowbar cannot lay a permanent foundation for socialism.” Expert concerns, which were expressed in the Gosplan by Vladimir Groman and Vladimir Basarow , for example , were attacked as cowardice by “deviants” with increased intolerance and militancy.

The cautious were ultimately silenced and the planning became more and more optimistic. Until the end of 1927, the majority of Gosplan assumed that major new investments would initially reduce the volume of industrial production. In the autumn of 1928 she assumed that industrial production would immediately increase slightly. In the final version of the five-year plan, industrial production growth of at least 135% was assumed, and under particularly favorable circumstances (including five very good grain harvests in a row) a growth of 180% is even possible. Ultimately, the Soviet Congress in April 1929 passed the five-year plan in this most optimistic version. In the summer of 1929, the Soviet leadership announced that the goals of the five-year plan would be achieved in four years.

Introduction of the grain delivery obligation

As early as 1927 it became apparent that the harvest expectations had been set too high. It was blamed on speculators who allegedly hoarded grain. There were waves of purges among party secretaries, chairmen of executive committees, members of the village Soviets and senior officials of the state trade organs. The village assemblies had to resolve "voluntary" special levies and an increase in the cooperative contributions. There were local peasant uprisings and the assassination of individual government officials. In the summer of 1928, the state government first tried to ease the situation, and the special measures were lifted again. But even in 1928 the harvests were significantly lower than expected and the state grain purchases remained well below target. The state government reintroduced the grain delivery obligation known from the time of war communism . Each village had to deliver a fixed amount of grain. This ended the New Economic Policy , which since 1921 had given agriculture greater free-market freedom. The food shortage was countered with rationing. Since mid-1929, normal earners and the non-privileged could only get barely rationed groceries from ration cards.

Forced collectivization and deculakization

Finally, Stalin decided to use open violence to force the peasants to join the large socialist enterprises ( collective farms or sovkhozes ). In December 1929 Stalin called for the "liquidation of the kulaks ". The kulaks were divided into three categories:

- 60,000 “counter-revolutionaries” who were to be imprisoned in gulags or, in the event of resistance, executed immediately.

- 150,000 "kulak activists" who were to be deported with their families to remote, sterile areas.

- The third group, around five to six million people, was to be partially expropriated and used as workers.

According to official standards, a kulak was anyone who had means of production worth at least 1,600 rubles, which corresponded to about ten horses or 13 cows. In practice, however, every farmer was treated as a kulak who opposed collectivization. With that the deculakization began . Deportation quickly became a death sentence for many families because they were sent without any means of production to a barren region, where they received no help in trying to rebuild their livelihoods. A not insignificant aspect of the deculacization was the expropriation of land, buildings, cattle and means of production, with which the often poorly equipped collective farms could be upgraded.

The measures caused some militant resistance from the peasants. In March 1930, Stalin decided to give in at short notice. He titled an article published in Pravda on March 2, 1930 , "Seized with dizziness before successes" and accused local actors of disregarding Lenin's principle of voluntariness. The peasants took the opportunity to leave the collective farms on a massive scale. According to historians, the closed season, which conspicuously coincided with the vegetation period, also had the meaning not to endanger the harvest any further. The 1930 harvest was generally satisfactory. However, it became apparent that the winter grain, which was still mainly grown by individual farmers, produced a significantly higher yield than the summer grain, which was mainly grown under the direction of the collective farms. Nonetheless, Stalin claimed at the 1930 party congress that collectivization had averted the grain crisis. In August 1930 the campaign for forced collectivization continued, this time with the persecution of "new kulaks" and "half-kulaks".

A total of 2.1 million people were deported to distant areas, 300,000 of whom died on the transport. 2 to 2.5 million people were resettled within their home region. It is estimated that around 530,000 to 600,000 people died as a result of the deculakization. 1 to 1.25 million people deculacized themselves by giving up everything and moving to the cities. By 1931 half of the farmers were incorporated into collective farms, and by 1936 almost all of them.

| 1.6.1928 | 1.6.1929 | October 1, 1929 | 1.1.1930 | 1.2.1930 | 1.3.1930 | 1.4.1930 | 1.7.1930 | October 1, 1930 | 1.1.1931 | 1.3.1931 | July 1, 1931 | July 1, 1932 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Share of households in collective farms in% of all farms | 1.7% | 3.9% | 7.5% | 18.1% | 31.7% | 57.2% | 38.6% | 22.5% | 21.8% | 25.9% | 35.3% | 55.1% | 61.5% |

Many farmers slaughtered their livestock before entering the kolkhoz. This resulted in a strong decimation of the livestock, so that in many places the fields could only be tilled with human strength. After the planning, tractors should replace the draft animals anyway. To flank the forced collectivization, the completion of 2,000 tractors was planned between July and September 1930. The Stalingrad tractor factory was completed in the summer of 1930 . In the planned period, however, only 35 tractors were produced, which also fell apart after 70 hours of work. The reasons were varied. For one thing, the plant had been assigned unusable steel. The copper tape for the cooler had already been delivered torn. The nuts came from a company that had previously manufactured nails and had to rush to change production. In addition, there were almost no experienced industrial workers available at the plants, so that hardly anyone was able to read the operating instructions for the (usually imported) machines. The bottlenecks and deficiencies were symptomatic of the problems caused nationwide by the rapid industrialization.

The autumn 1931 harvest brought an all-time low. The reason was the reduction in the area under cultivation, the shrinking of the livestock and the significantly lower yield per hectare in kolkhozes and sovkhozes compared to the yield per hectare of individual farmers. As a result of the loss of animal traction and the largely lack of mechanical traction, the area under cultivation for grain in Ukraine, for example, decreased by 14% and the harvest volume even decreased by 20%. The coming famine was already evident in the autumn of 1931.

Gareth Jones visited the Soviet Union in 1933 as an investigative journalist and reported on the causes of the famine:

“Last year, the weather was ideal… Then why the catastrophe? In the first place the land has been taken away from 70 percent of the peasantry, and all incentive to work has disappeared. In the second place, the cow was taken away from the peasant ... The result of this policy was a widespread massacre of cattle by the peasants, who did not wish to sacrifice their property for nothing. Another result was that on these State cattle factories, which were entirely unprepared and had not enough sheds, innumerable livestock dies of exposure and epidemics. Horses died from lack of fodder. "

“Last year [1932] the weather was ideal, so why the disaster? First of all, 70% of the smallholders had their land taken away and all incentives to work disappeared. Second, the cows were taken away from the smallholders. As a result, the smallholders massacred their livestock widely because they did not want to sacrifice their property for nothing. Another result was that the state cattle ranches were unprepared and did not have enough sheds. Countless cattle died from exposure and epidemics. Horses died because there wasn't enough food. "

Famine 1932-1933

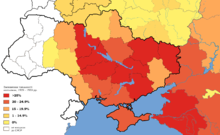

The 1932 harvest hit a new low. Nonetheless, fixed amounts of foodstuffs were requisitioned from the peasants, which had been determined on the assumption of much better harvests. The result was a famine that particularly affected the fertile rural areas. According to various estimates, 5 to 9 million people died of starvation, especially many in Ukraine and Kazakhstan.

During this time, the Soviet Union sold more than a million tons of wheat on the world market in order to be able to buy machinery needed for industrialization.

- Famine from 1932-33

Guard post in Kharkiv Oblast (1934)

Starving deaths on a sidewalk in Kharkiv (Photo by Alexander Wienerberger, 1933)

Reactions

The consequences of forced collectivization were denied by the government and the state media until the 1980s. When the population fell in the 1937 census, the statisticians involved were executed. Gareth Jones was one of the first foreign journalists to report on the situation in the Soviet Union. George Orwell wrote Animal Farm as an allegory of forced collectivization and the Great Terror in the Soviet Union.

See also

Web links

- Articles on collectivization in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine (English)

Individual evidence

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica, Collectivization

- ↑ Manfred Hildermeier, The Soviet Union 1917-1991 , Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 2016, ISBN 9783110398892 , Chapter 3.2 Forced collectivization

- ↑ Helmut Altrichter, Little History of the Soviet Union 1917-1991 , CH Beck, 2013, 4th edition, ISBN 9783406657689 , p. 68.

- ↑ Manfred Hildermeier, History of the Soviet Union, 1917-1991: The emergence and decline of the first socialist state , CH Beck, 1998, ISBN 9783406435881 , pp. 369–371.

- ↑ Helmut Altrichter, Little History of the Soviet Union 1917-1991 , CH Beck, 2013, 4th edition, ISBN 9783406657689 , pp. 68–69.

- ↑ Helmut Altrichter, Little History of the Soviet Union 1917-1991 , CH Beck, 2013, 4th edition, ISBN 9783406657689 , p. 70.

- ↑ Helmut Altrichter, Little History of the Soviet Union 1917-1991 , CH Beck, 2013, 4th edition, ISBN 9783406657689 , p. 70.

- ↑ Manfred Hildermeier, The Soviet Union 1917-1991 , Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 2016, ISBN 9783110398892 , Chapter 3.2 Forced collectivization

- ^ Manfred Hildermeier, History of the Soviet Union, 1917-1991: Origin and decline of the first socialist state , CH Beck, 1998, ISBN 9783406435881 , p. 375.

- ↑ Helmut Altrichter, Little History of the Soviet Union 1917-1991 , CH Beck, 2013, 4th edition, ISBN 9783406657689 , pp. 73–74.

- ↑ Federal Agency for Civic Education, Susanne Schattenberg, Manuela Putz, Stalinism , August 5, 2014.

- ^ Manfred Hildermeier, History of the Soviet Union, 1917-1991: Origin and decline of the first socialist state , CH Beck, 1998, ISBN 9783406435881 , p. 395.

- ↑ Manfred Hildermeier, History of the Soviet Union, 1917-1991: The emergence and decline of the first socialist state , CH Beck, 1998, ISBN 9783406435881 , pp. 396-397.

- ^ Manfred Hildermeier, History of the Soviet Union, 1917-1991: Origin and decline of the first socialist state , CH Beck, 1998, ISBN 9783406435881 , p. 398.

- ↑ Manfred Hildermeier, The Soviet Union 1917-1991 , Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 2016, ISBN 9783110398892 , Chapter 3.2 Forced collectivization

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica, Collectivization

- ^ Manfred Hildermeier, History of the Soviet Union, 1917-1991: Origin and decline of the first socialist state , CH Beck, 1998, ISBN 9783406435881 , p. 389.

- ^ Manfred Hildermeier, History of the Soviet Union, 1917-1991: Origin and decline of the first socialist state , CH Beck, 1998, ISBN 9783406435881 , p. 376.

- ^ Manfred Hildermeier, History of the Soviet Union, 1917-1991: Origin and decline of the first socialist state , CH Beck, 1998, ISBN 9783406435881 , p. 399.

- ↑ quoted from: Benjamin Lieberman, The Holocaust and Genocides in Europe , Bloomsbury Publishing, 2013, ISBN 9781441110800 , chapter: terror and Famine before the Second World War

- ↑ Helmut Altrichter, Little History of the Soviet Union 1917–1991 , CH Beck, 2013, 4th edition, ISBN 9783406657689 , p. 73.

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica, The famine of 1932-33

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica, The famine of 1932-33

- ^ Benjamin Lieberman, The Holocaust and Genocides in Europe , Bloomsbury Publishing, 2013, ISBN 9781441110800 , chapter: terror and Famine before the Second World War

- ^ Benjamin Lieberman, The Holocaust and Genocides in Europe , Bloomsbury Publishing, 2013, ISBN 9781441110800 , chapter: terror and Famine before the Second World War

- ↑ Harold Bloom, George Orwell's Animal Farm , Infobase Publishing, 2009, ISBN 9781438128719 , p. 120.