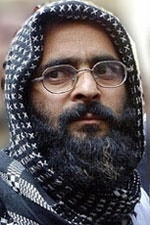

Afzal Guru

This article possibly contains original research. (February 2021) |

Afzal Guru | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Mohammed Afzal Guru June 1969 |

| Died | 9 February 2013 (aged 43) |

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Education | University of Delhi |

| Known for | Role, conviction and execution in the 2001 Indian Parliament attack |

| Criminal status | Executed |

| Spouse | Tabasum Guru[1] |

| Children | Galib Guru |

| Parent(s) | Habibullah (father)[1][2] Ayesha Begum (mother)[1] |

| Allegiance | Jaish-e-Mohammad |

| Motive | Islamic extremism and separatism |

| Conviction(s) | Murder Conspiracy Waging war against India Possession of explosives |

| Criminal charge | 2001 attack on the Parliament of India |

| Penalty | Death |

Date apprehended | 21 December 2001 |

Mohammad Afzal Guru (June 1969 – 9 February 2013) was a radical Jihadist [3][4] who was convicted for his role in the 2001 Indian Parliament attack. He received a death sentence for his involvement, which was upheld by the Indian Supreme Court. Following the rejection of a mercy petition by the President of India, he was executed on 9 February 2013. His body was buried within the precincts of Delhi's Tihar Jail.[5]

He was a member of a Pakistan-based Deobandi terrorist organisation Jaish-e-Mohammed.[3][4]

Early life[edit]

Guru was born in Du Aabgah village near Sopore town in the Baramulla district of the erstwhile Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir in 1969 to the family of Habibullah.[6][7] Habibullah ran a timber and transport business, and died when Guru was a child. Guru completed his schooling from Government School, Sopore and passed the matriculation exam in 1986. He subsequently enrolled in the Jhelum valley medical college. He had completed the first year of his MBBS course and was preparing for competitive exams when he began to participate in other activities.[6][8]

Training[edit]

Afzal's native place was Sopore. There, he ran a commission agency in fruits.[9] It was during this business venture that he came into contact with Tariq, a man from Anantnag, who motivated him to join Jihad for the liberation of Kashmir.[citation needed] He crossed the Line of Control and proceeded to Muzaffarabad, Pakistan administered Kashmir. There, he became a member of the Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front and then returned to Sopore shortly afterward to lead 300 rebels.[citation needed] He did odd jobs and completed his graduation from Delhi University in the year 1993–94.

Shaukat who was a friend of Geelani, made Guru visit Geelani and they used to discuss Jihad and the "liberation" of Kashmir at length.[citation needed] In the summer of 1993–94, on the advice of his family, he surrendered to the Border Security Force and returned to Delhi where he worked till 1996.[7][8] He took up a job with a pharmaceuticals firm and served as its area manager. Simultaneously, he worked as a commission agent for medical and surgical goods in the year 1996. During this period, he used to shuttle between Srinagar and Delhi.[6] On a visit to Kashmir in 1998, he married a Baramulla native, Tabasum.[6]

The attack[edit]

The 13 December 2001 attack was conducted by the Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM). Gunmen sneaked into the Parliament in a car with Home Ministry and Parliament labels. They drove into the then Vice President Krishna Kant's car parked in the premises and began firing. The ministers and MPs escaped unhurt. The attack was foiled due to the immediate reaction of the security personnel present at the spot and complex. There was a fierce gun-battle lasting for nearly 30 minutes. Nine persons including eight security personnel and one gardener lost their lives in the attack and 16 persons including 13 security personnel, received injuries. The five assailants were killed.[10][11] At the end of December, US President George W. Bush made a telephone call to Pakistan President Pervez Musharraf and Indian Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee to defuse tension between the two countries and urge them to move away from escalating the Parliament attack into war.[12][13][14]

The trial[edit]

Investigation and arrest[edit]

On 15 December 2001, the special cell of Delhi Police, with the help of leads relating to the car used and cellphone records, arrested Guru from Srinagar, his cousin Shaukat Husain Guru, Shaukat's wife Afsan Guru (Navjot Sandhu before marriage) and S A R Gilani, a lecturer of Arabic at Delhi University were also arrested by the police.[2][15]

On 13 December an FIR was lodged by the police and after subsequent arrests, all the accused were tried under charges of waging war, conspiracy, murder, attempt to murder etc. with the provisions of the Prevention of Terrorism Act, 2002 (POTA) being added to the original charges after six days. On 29 December 2001, Guru was sent to 10-day police remand.[11] The court appointed Seema Gulati as his lawyer. who dropped Guru's case after 45 days because of her case load.[16] In June 2002, charges were filed against all four of them.[11] 80 witnesses were examined for the prosecution and 10 witnesses were examined on behalf of the accused.[14]

Charges[edit]

Guru was charged under several sections of POTA and the Indian Penal Code including waging of war against the Government of India and conspiracy to commit the same; murder and criminal conspiracy; conspiring and knowingly facilitating the commission of a terrorist act or acts preparatory to a terrorist act, and also voluntarily harbouring and concealing the now-deceased terrorists, knowing that such persons were terrorists and were members of the Jaish-e-Mohammad, and possession of ₹ 10 Lakhs given to him by the terrorists who were killed by the police when they attacked the Parliament.[17] Police filed a charge-sheet in the case on 15 May 2002. The trial started after charges were laid against the four accused on 4 June 2002.[18]

Confession[edit]

After his arrest, Guru made a confessional statement which bore his signature, recorded by the DCP, special cell. It was recorded in the preamble of the confession that DCP had asked policemen present there to leave the room.[14][19] The Supreme Court was angered by the act of police officials, who, in their over-zealousness, had arranged for a media interview.[19] However, after seven months, Guru disowned this confession and the Supreme Court did not accept the earlier confession as evidence against him.[19]

Sushil Kumar, Guru's advocate later claimed that Guru had written a letter to him where Guru said that he had made the confessions under duress as his family was being threatened.[20] Journalist Vinod K. Jose claimed that in an interview in 2006, Guru had said that he had been subjected to extreme torture which included electric shocks in private parts and being beaten up for hours along with threats regarding his family after his arrest.[21] Between the time of his arrest and the time when initial charges were filed, Guru was told that his brother was held in detention.[21] At the time of his confession, he had no legal representation.[16][21]

Conviction[edit]

On 22 December 2001, the case was brought before a special POTA Court under sessions judge S N Dhingra and the trial started on 8 July 2002, and was conducted on a day-to-day basis. Eighty witnesses were examined for the prosecution and ten were examined for defence. Trial was concluded in nearly six months.[14]

On 18 December 2002, relying on the circumstantial evidence, the special court awarded capital punishment to Guru, Shaukat and Geelani. Shaukat's wife Afsan was found guilty of concealing the plot and sentenced to five years in jail. The POTA court justified capital punishment, saying the attack on Parliament was the handiwork of forces which wanted to "destroy the country and cripple it by killing or capturing its entire political executive, including the Prime Minister and the Home Minister... captivate entire legislature and the Vice-President, who were in Parliament." He was also sentenced to life imprisonment on as many as eight counts under the provisions of IPC, POTA and Explosive Substances Act in addition to varying amounts of fine.[11][14][15] In August 2003, Jaish-e-Mohammed leader Ghazi Baba, who was a prime accused in the attack was killed in an encounter with the Border Security Force (BSF) in Srinagar. In October 2003, on an appeal, Delhi High Court upheld the order.[22]

Delhi High Court[edit]

An appeal was made to the Delhi High Court, but after going through the case and taking into consideration various authorities and precedents, the Court found that the conviction of Guru was correct and hence his appeal was dismissed. Guru was represented by senior counsel Shanti Bhushan and Colin Gonsalves.[citation needed] The co-accused in the case, SAR Geelani and Afsan Guru (wife of Shaukat Husain), were acquitted by the High Court 29 October 2003.[11][23][24][25]

Supreme Court of India[edit]

On 4 August 2005, the Supreme Court, upheld the death sentence for Afzal Guru while it commuted Shaukat Hussain Guru's sentence from death to 10 years imprisonment.[11][26] Of the three sentenced to death, SAR Geelani (who was presented as the mastermind behind the attack), Shaukat Hussain Guru and Afzal Guru, only Afzal Guru's penalty was upheld by the Supreme Court.[2][25] Guru filed a review petition before the Supreme Court seeking review of its judgement. However, on 22 September 2005, the review petition too came to be dismissed by the Supreme Court.[18]

In its judgement, the Supreme Court observed:

"As criminal acts took place pursuant to the conspiracy, the appellant, as a party to the conspiracy, shall be deemed to have abetted the offence. In fact, he took active part in a series of steps taken to pursue the objective of conspiracy."

Supreme Court of India, Judgement on Appeal by Guru on 5 August 2005.[19][26]

The Supreme Court observed that mostly, the conspiracies are proved by the circumstantial evidence.[27] It held that the circumstances detailed in the judgment clearly established that Guru was associated with the deceased militants in almost every act done by them in order to achieve the objective of attacking the Parliament House. It also observed that there was sufficient and satisfactory circumstantial evidence to establish that Guru was a partner in this conspired crime of enormous gravity. It has to be noted, that in its judgement of 5 August 2005, the supreme court admitted that the evidence against Guru was only circumstantial, and that there was no evidence that he belonged to any terrorist group or organisation. He was subsequently meted out three life sentences and a double death sentence.[14]

In October 2006, Guru's wife Tabasum Guru filed a mercy petition with then President of India A. P. J. Abdul Kalam. In June 2007, Supreme Court dismissed Guru's plea seeking review of his death sentence, saying "there is no merit" in it. In December 2010, Shaukat Hussain Guru was released from Delhi's Tihar Jail due to his good conduct.[11]

Clemency pleas[edit]

There was an appeal to issue clemency to Guru from various human rights groups including political groups in Kashmir,[28] who believe that Guru did not receive a fair trial and was framed by corrupt police and the victim of inefficient police work.[29] Human rights activists in various parts of India and the world have demanded reprieve as they believe that the trial was flawed. Arundhati Roy and Praful Bidwai castigated the trial and argued that Guru has been denied natural justice.[30] Accusations of human rights violations have been made by many.[31][32]

Former Jammu and Kashmir Chief Minister Mufti Mohammed Sayeed and local political groups voiced their support of clemency for Guru. It was alleged many have done so to appease Muslim voters in India.[33] However, there were protests (with instances of stone pelting at Indian security forces) in Kashmir against the planned execution of Guru in 2006.[citation needed]

Communist Party of India (Marxist) was critical of both the Congress as well as of the BJP, and claimed it was delaying the legal procedure in the case accusing it of trying to whip up enmity between communities in the name of a crime done by a group of criminals. The party wants the law of the land to take its course without any interference.[34]

Ram Jethmalani held that it is completely within the president's power to commute the death sentence and is not a mercy plea. He said, "It’s a misnomer to call it a mercy petition. It leads to total misunderstanding of the constitutional power. The constitutional power is that the president has the power to disagree with the Supreme Court both with its findings of fact and law."[35] The case became political and it was not carried out because of fear of revenge attacks. The Jammu and Kashmir People's Democratic Party president and MP, Mehbooba Mufti commented that the centre should pardon Afzal if Pakistan accepted the clemency appeal for Sarabjit Singh.[36]

However, the All-India Anti-Terrorist Front Chairman Maninderjeet Singh Bitta urged the President of India not to accept any clemency pleas on Afzal's behalf. He warned that his organisation would launch agitations if Afzal was pardoned. He also criticised statements of various political leaders and blamed them for "encouraging activities of terrorists in Jammu and Kashmir".[37]

An India Today poll in October 2006 showed that 78% of Indians supported the death penalty for Afzal.[33]

On 12 November 2006, the former Deputy Prime Minister of India, Lal Krishna Advani criticised the delay in carrying out the death sentence on Guru for the Parliament terror attack, saying, "I fail to understand the delay. They have increased my security. But what needs to be done immediately is to carry out the court's orders".

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) severely criticised Arundhati Roy. BJP spokesperson Prakash Javadekar said:

"Those who are supporting Afzal by demanding that he should not be hanged are not only acting against public sentiment in the country but are giving a fillip to terrorist morale"[38]

On 23 June 2010, the Ministry of Home Affairs recommended the president's office to reject the mercy petition. On 7 January 2011, a whistle-blowing site indianleaks.in leaked a document which stated that the mercy petition file was not with President of India. This was rubbished by Kapil Sibal in an interview with NDTV.[39] This was confirmed by Home Minister P. Chidambaram in New Delhi on 23 February 2011. With the death penalty handed to Ajmal Kasab, the speculation was that Guru was next in line.[40]

On 10 August 2011, the home ministry of India rejected the mercy petition, and sent a letter to the President of India recommending the death penalty .[41]

On 7 September 2011, a high intensity bomb blast outside Delhi high court killed 11 people and left 76 others injured.[42] In an e-mail sent to a media house Harkat-ul-Jihad al-Islami, an Islamic fundamentalist organisation, owned responsibility for the attack and claimed the blast was carried out in retaliation to Parliament attack convict Guru's death sentence.

"We own the responsibility for today's blasts at Delhi high court. Our demand is that Mohammed Afzal Guru's death sentence should be repealed immediately else we would target major high courts and the Supreme Court of India."[43]

Later on Afzal Guru in his letter[which?] declared the attack on Delhi High Court that killed 11 Indians against the principles of Islam and refuted all allegations with the attack.[44]

Execution[edit]

On 16 November 2012, the president had sent seven cases back to the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA), including Afzal Guru's. The president requested Sushil Kumar Shinde, home minister, review the opinion of his predecessor, P. Chidambaram. On 10 December, Shinde indicated he would look at the file after the winter session of the Parliament was finished on 20 December.[11][45][46][47] Shinde made his final recommendation to execute Guru on 23 January 2013.[48] On 3 February 2013, Guru's mercy petition was rejected by the President of India.[11][48]

Afzal Guru was hanged six days later on 9 February 2013 at 8 am.[49] Jail officials have said that when Guru was told about his execution, he was calm. He expressed his wish to write to his wife. The jail superintendent gave him a pen and paper. He wrote the letter in Urdu, which was posted to his family in Kashmir the same day. Very few officers were told about the decision. Three doctors and a maulvi, who performed his last rites, were informed secretly a night before. They were asked to come early Saturday morning. Guru performed his morning prayers and read a few pages of the Quran. Guru's letter was delivered to his family on 12 February.[50][51] Kobad Ghandhy, who spent three years with Afzal in Tihar, wrote that Afzal asked jail authorities to treat the jail staff well and that the staff wept for Afzal.[52][53] The execution of Mohammed Afzal Guru was named Operation Three Star.

Guru's family was informed of his execution two days after by a letter sent through Speedpost, a fast courier service, to their home in Sopore.[54] Postal officials in Srinagar said they received the letter Saturday evening (9 February), but it could not be delivered until Monday (11 February) because Sunday was a public holiday.[55]

Aftermath of execution[edit]

The secret operation surrounding the execution of Afzal Guru was code named Operation Three Star.[1] The prison took steps to execute Guru in secrecy.[54] The execution was carried out without the family's knowledge or any form of public announcement.[56][57][58] Guru's body was buried on prison grounds to prevent a public funeral.[54]

On a national level, security was prepared beforehand for public protests.[54] After Guru' s execution, a curfew was then imposed by the authorities when the news became public in Kashmir to prevent any kind of protests in support of Guru.[59] State-run media Doordarshan announced the execution on the morning of 9 February, and Omar Abdullah, chief minister of Jammu and Kashmir state, made a special appeal on television for public calm.[49][60][61] Authorities also shut down cable TV and internet services to try to stop further news of the hanging and activists from organizing and spreading unrest.[62]

Mosques throughout the region were used for public announcements and curfew information.[10] SAR Geelani, who was co-accused in the attacks on the Indian parliament and later acquitted by the Supreme Court,[26] was taken into preventive custody by the Delhi Police.[57] Several leaders from the separatist movement were also detained.[56] However, protests flared up in parts of the Valley—Guru's hometown of Sopore, Baramulla in North Kashmir and Pulwama in South Kashmir—and groups of young men broke curfew and threw stones at security forces.[62][63] Police fired at protesters, and 36 people were injured, including 23 policemen, said a police spokesperson, particularly around Guru's home district where most of the violence was concentrated.[56][60][63]

There were scuffles in Delhi too, where Bajrang Dal and Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP) members were celebrating the hanging of Afzal Guru. Soon Kashmiri students from Delhi University and Jawaharlal Nehru University accompanied by members of CPI(M-L), Peoples Union for Democratic Rights (PUDR) and National Confederation of Human Rights Organisations (who were condemning capital punishment) started a counter-protest in support of Afzal Guru and chanted slogans in support of an independent Kashmir. Tensions escalated as the rival protests took on a communal hue when both groups raised religious slogans and scuffled with each other as police struggled to keep them separated. Protesters holding protests on different issues too joined the foray against the Kashmiri students. The situation was brought under control by policemen in riot gear who bundled the students into waiting buses and drove them away. Delhi police lathi charged protestors at Jantar Mantar. The police detained at least 21 Kashmiri students. Female students were also assaulted.[64][65]

Involved parties[edit]

In an interview in 2006 with Jose, Guru said, "If you want to hang me, go ahead with it, but remember it will be a black spot on the judicial and political system of India."[21]

In the letter written before his death, Guru wrote, "I am about to be hanged. Now, near the gallows, I want to tell you (family members) that I was not given enough time to write a detailed letter. I am thankful that Allah (God) chose me for this sacrifice. And please, take care of Tabasum and Galib."[1]

SAR Geelani condemned Afzal Guru's hanging was a "cruel and politically motivated gimmick" and a " politically motivated decision."[58]

Justice SN Dhinga, the Judge who sentenced Guru and co-accused Shaukat Guru and SAR Geelani to death in 2002, termed the execution a political move stating that the judiciary took just three years to decide the matter while the executive took eight years to implement the same[66]

International Human Rights Groups[edit]

Amnesty International condemned the execution saying that it 'indicates a disturbing and regressive trend towards executions shrouded in secrecy'. Shashikumar Velath, Programmes Director at Amnesty International India said "We condemn the execution in the strongest possible terms. This very regrettably puts India in opposition to the global trend towards moving away from the death penalty".[67]

Pakistan[edit]

In April 2013, Pakistan President Asif Ali Zardari condemned the execution of Afzal Guru inside the Pakistan-controlled Kashmir region. The President said, "The hanging of Afzal Guru through the abuse of judicial process has further aggravated and angered the people of Kashmir."[68]

Political parties[edit]

Most political parties[69] with exception of Kashmiri politicians welcomed the move by the Government of India. The BJP stated that it was a correct move albeit very late. It also stated that the public opinion forced Afzal Guru's hanging.[70][71]

A leader from the Bharatiya Janata Party, then Chief Minister of Gujarat now Prime Minister Narendra Modi, tweeted "better late than never" after the news of Guru's execution by hanging had been announced.[10] Modi had previously been critical of the government for delaying Guru's execution after the Supreme Court's final decision.[72]

Jammu and Kashmir People's Democratic Party spokesman Naeem Akhtar also criticised Guru's burial inside the prison complex in New Delhi, saying the body should have been given to his family in Kashmir.[71] The All Parties Hurriyat Conference announced a four-day mourning on the death of Guru.[71] The Prime Minister of Azad Kashmir, announced three-day mourning and the Kashmir flag waved at half mast.[73]

Jammu and Kashmir chief minister Omar Abdullah has been highly critical about Afzal Guru's hanging. He said the "biggest tragedy" of the execution was that he was not allowed to meet his family before he was hanged. He also suggested that the centre was "selective" in avenging attacks on symbols of democracy and backed the allegation that the legal process in the Parliament attack mastermind Afzal Guru's case was "flawed".[74]

Omar Abdullah's father, Former Chief Minister of Jammu and Kashmir, Union minister Farooq Abdullah said: "Afzal Guru’s mercy petition was put before the President. He rejected it. The matter is over."[75]

Legal experts[edit]

The Hindu published in an article by Praveen Swami where he mentioned that legal experts have cast no small doubt on whether Guru received a fair trial, whether his guilt was proved and whether his death penalty was legitimate. It was cited that the debates on this case had engaged some of India's finest legal minds for months, both on the side of the state and defence. He also mentioned that the key actors in the attack were likely to get away, because no one could investigate them. In his words, "We are still far from knowing the full truth of 13/12. It is likely that many of the unanswered questions might resolve themselves if Pakistan were ever to arrest Jaish-e-Muhammad chief Maulana Masood Azhar — currently living, in some luxury, in his Bahawalpur home. Nothing in recent experience – witness the 26/11 case – suggests this will happen"

However, Swami was very critical of Arundhati Roy for asserting that political parties and the media all colluded to do something terribly wrong.[76]

The press[edit]

Although the press in India has been broadly supportive of Guru's hanging[citation needed], a section of the press criticised the manner in which the execution was carried out. In particular, the Times of India pointed out that since assumption of office as president Pranab Mukherjee had turned down three clemency petitions – Ajmal Amir Kasab, Afzal Guru and Saibanna Ningappa Natekar.[77] The Times of India highlighted the possible lack of due process evident in the government's failure to comply with the stipulation of the jail manual to inform Guru's family about the date of the execution. The compromise is more evident in Guru's case because, unlike Kasab, his family members are Indians, who live in Kashmir. The rationale behind this stipulation is to provide the convict a chance to meet his family members for the last time.[77]

In a different article, the Times of India also noted that "There's no doubt, therefore, that the crime of which Afzal has been convicted falls in the "rarest of rare" category. In the event he's gone through due process, as exemplified in the acquittals or lesser sentencing of all three of his co-accused through various stages of the judicial process, depending on quality of evidence. Once the president rejected his mercy petition the government had no option but to carry out the death sentence."[78]

However in another article, it was observed in The Hindu that though judicial determination will be – and ought to be – subjected to continued critical scrutiny but there is nothing to show the judicial system was blind to Guru’s legal rights. The article also criticised the journalists and political leaders of 'a certain kind' for not dealing with the "full truth".[76] Dawn observed that the timing in which he was executed was clearly an attempt to thwart the impending criticism of the economy's dwindling growth rate which had reportedly come down to a 10-year low of five per cent. The hanging was also expected to make the Congress party look as hardline as the BJP. The demeanour is considered useful with the urban middle class voter.[79]

Victims' families[edit]

The families of victims of the 2001 parliament attack said that they will write to president Pranab Mukherjee to get back the bravery awards returned by them earlier. The families had earlier returned the medals to protest the delay in hanging.[80]

Home minister[edit]

Indian Union Home Minister Sushilkumar Shinde said that Afzal Guru's family was informed about the hanging decision on time. But the family was not aware of Guru's hanging since the Speed post letter sent by the Tihar jail authorities regarding the hanging of Afzal reached his family 2 days after his hanging.[81][82] He defended the secrecy government maintained in the execution saying that it would not have happened had the decision been made public in advance.[83] He also denied the Jammu and Kashmir Chief Minister Omar Abdullah's charge that he was kept in the dark about the centre's decision to hang him. He said: "I personally informed Omar about the execution. Also, the family of Afzal Guru was informed on the night of 7 February." Asserting the need to maintain secrecy, Shinde said, "This, as Ajmal Kasab's case, was extremely sensitive, government had to be very careful. Secrecy has to be maintained in such cases."[84] He also picked holes in Omar Abdullah's assertion that Parliament attack convict Guru's hanging was "out of turn."[75]

Lawyers' suspension[edit]

On 13 February, few days after Guru's execution, lawyers N D Pancholi and Nandita Haksar withdrew as his family's counsel, citing "unseemly controversies" and "suspicion" by certain political groups in Kashmir. Without elaborating on the immediate reasons for their decision they said that in Kashmir some political groups feel these offers of solidarity and friendship with suspicion.[85]

Handing over Guru's remains[edit]

Guru's wife, Tabasum, had sought to claim his body which was buried in the Tihar Jail. However the Central government is likely to reject the request citing the Jail manual. The Delhi Jail manual states that the body may not be transferred to family/friends "if there are grounds for supposing that the prisoner's funeral will be an occasion for a demonstration".[86]

Bibliography[edit]

Books by him[edit]

- Ahle Imaan Ke Naam Shaheed Mohammad Afzal Guru Ka Aakhri Paigam (Martyr Afzal Guru's Last Message to the Peoples of Faith), 2013. Released seven months after his hanging, this 94-page book, a compilation of diaries, calls for a renewed jihad against India and takes as model the Talibans and Mullah Omar. More than 5,000 copies of the book were printed and circulated, and for the book release a function was attended by Afzal's brother, Aijaz Guru.[87]

- Aina (Mirror), Maktab-e-Irfan, Lahore, 2013. This book, ostensibly written by Afzal Guru while in Tihar jail, was published by Jaish-e-Mohammed ten months after his hanging. It contains 132 short chapters attributed to Guru that talk about jihad, the situation in Kashmir, messages to the youth and other ideological issues. The book also has introductory and laudatory pieces written by Masood Azhar, who said that Afzal wrote it in 2010 but couldn't find a publisher, as well as by other Jaish-e-Mohammed members.[88] The book's use by later militants like Zakir Musa led the police to see Afzal Guru as having become an "insurgent spiritual leader".[89]

Books about him[edit]

- Framing Geelani, hanging Afzal: Patriotism in the time of terror by Nandita Haksar, 2007. [90]

- The Afzal petition: A quest for justice by Nandita Haksar (editor), 2007. [91]

- Phānsī (Hanging) by Shabnam Qayyum, 2013. [92]

- The hanging of Afzal Guru and the strange case of the attack on the Indian parliament edited by Arundhati Roy, 2013.[93]

See also[edit]

- Hurriyat and Problems before Plebiscite

- Syed Ali Shah Geelani

- Kashmir conflict

- 2014 Jammu and Kashmir Legislative Assembly election

- 2001 Indian Parliament attack

- Jaish-e-Mohammed

- Terrorism in India

- Capital punishment in India

- Human rights abuses in Jammu and Kashmir

- Human rights abuses in Azad Kashmir

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e Anwar, Tarique (16 February 2013). "Afzal Guru in last letter to family: 'Take care of my wife and son'". Daily Bhaskar. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ^ a b c "Delhi High Court – State vs Mohd. Afzal And Ors". Indian Kanoon. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ a b Jaffrelot, Christophe (2015). The Pakistan Paradox: Instability and Resilience. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-023518-5.

- ^ a b "Afzal Guru: A chronology of events". The Hindu. 9 February 2013. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- ^ "Afzal Guru: A chronology of events". The Hindu. 3 December 2002. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- ^ a b c d Who is Afzal Guru – One India News. Retrieved 9 February 2013

- ^ a b State v. Mohammad Afzal and Ors., Judgment of High Court of Delhi in Murder Reference No. 1/2003 and Crl. A. No. 43/2003 by J. Usha Mehra and J. Pradeep Nandrajog 9 October 29, 20030

- ^ a b "Afzal Guru hanged, buried in Tihar". DNA. 9 February 2013. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ "Guru: A commission agent in fruits business". Deccan Herald. 9 February 2013. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- ^ a b c Magnier, Mark (9 February 2013). "India executes Afzul Guru for 2001 parliament attack". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Afzal hanging: From arrest till the noose". DNA. Press Trust of India. 9 February 2013. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ Keerthana, R (15 February 2013). "The Afzal Guru story". The Hindu. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- ^ Broughton, Philip Delves; Bedi, Rahul (31 December 2001). "Bush urges India and Pakistan to avert war". The Daily Telegraph (UK).

- ^ a b c d e f "State (N.C.T. Of Delhi) vs Navjot Sandhu@ Afsan Guru". Supreme Court of India. 4 August 2005. Archived from the original on 20 October 2016. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ^ a b Anand, Utkarsh (10 February 2013). "The legal journey of Afzal Guru". Indian Express. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- ^ a b Roy, Arundhati (19 October 2006). "Clemency-seekers weakened Afzal's defence". The Times of India. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ Choudhury, Sunetra (14 January 2020). "Davinder link wouldn't have affected verdict, says judge in Afzal Guru trial". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 14 January 2020. Retrieved 6 September 2023.

- ^ a b "SC Refuses To Review Judgement in Parliament Attack Case". Indlaw. 22 September 2005. Archived from the original on 20 September 2014. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ^ a b c d "The Case of Mohd. Afzal". Outlook. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ "I Hope My Forced Silence Will Be Heard". Outlook. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- ^ a b c d Jose, Vinod K. "Mulakat Afzal". Caravan Magazine. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- ^ Sinha, Ashish (30 August 2007). "How intelligence got it right on Ghazi Baba". Times of India. TNN. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ^ PTI news agency (20 February 2004). "Indian Supreme Court stays execution of parliament attack convict". BBC Monitoring International Reports (Subscription). Asia Africa Intelligence Wire. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ "All you need to know about the 2001 Parliament attack". Firstpost. 9 February 2013. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- ^ a b Roy, Arundhati (15 December 2006). "India's shame". London: Guardian (UK). Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ a b c "The Case of SAR Gilani". Outlook. Archived from the original on 12 February 2013. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ "Full text: Supreme Court judgement on Parliament attack convict Afzal Guru". Supreme Court of India. Archived from the original on 12 February 2013. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- ^ Khan, Mehboob (29 September 2011). "Kashmir uproar over Afzal Guru clemency plea". BBC News. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ^ "Why Afzal Must not Hang". Democracy Org. Retrieved 9 September 2011.

- ^ Roy, Arundhati (15 December 2006). "India's shame". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ INDIA: NEW EXECUTION POINTS TO WORRYING AND REGRESSIVE TREND, Amnesty International, 9 February 2013.

- ^ "Afzal Guru's secret hanging a human rights violation: Prosecutor | India News - Times of India". The Times of India. 13 February 2013.

- ^ a b (30 October 2006). No Mercy. India Today, [5(43)], [14–15].

- ^ Playing With National Security Archived 30 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine People's Democracy

- ^ "The People's Paper". Tehelka. 28 October 2006. Archived from the original on 1 December 2006. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ^ "Pardon Afzal: Mehbooba". The Hindu. 31 August 2005. Archived from the original on 19 December 2007. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Bitta urges President not to pardon Afzal". The Times of India. 8 November 2006.

- ^ "BJP flays Arundhati Roy for 'defending' Afzal". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 23 November 2006.

- ^ "Afzal Guru Mercy petition file is not with President of India!". Indian Leaks. 7 January 2010. Archived from the original on 13 January 2011. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- ^ "Afzal Guru's mercy petition not yet sent to president: Chidambaram". Deccan Herald. 23 February 2011.

- ^ "Home Ministry rejects Afzal Guru's mercy petition". CNN-IBN. 10 August 2011. Archived from the original on 17 July 2012.

- ^ "11 dead, 76 injured in terror strike". Hindustan Times. 7 September 2011. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ^ "HuJI claims responsibility for Delhi high court blast". The Times of India. 7 September 2011. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ^ "Don't link me with blast: Afzal Guru". The Indian Express. 9 February 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ Sharma, Aman (11 December 2012). "Sushil Kumar Shinde to look into Parliament attack accused Afzal Guru's file after winter session". The Times of India. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ^ "Shinde to look Afzal Guru's mercy plea after Winter Session". Hindustan Times. 10 December 2012. Archived from the original on 12 February 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ^ "Decision on Afzal Guru's mercy petition in fortnight?". Hindustan Times. 13 December 2012. Archived from the original on 15 January 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ^ a b "Afzal Guru, Parliament attack convict, hanged in Delhi's Tihar Jail". NDTV.com. 20 October 2006. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ^ a b "Parliament attack convict Afzal Guru has been hanged". TDNPost. 9 February 2013. Archived from the original on 11 April 2013.

- ^ "In last letter to wife, Afzal Guru named hanging code Operation Three Star". IBN 7. 12 February 2013. Archived from the original on 12 February 2013. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ^ "Afzal Guru's last letter delivered to family". NewsWala. 15 February 2013. Archived from the original on 27 February 2013. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ^ "Afzal had deep dislike for Pakistan, ISI: Khobad Gandhy in letter to journalist". Hindustan Times. 10 February 2017. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ Thapar, Karan (14 March 2021). "Kobad Ghandy on Tihar: 'Jailers Wept for Afzal; Nirbhaya Rapist Vinay Sharma Was a Vile Sort'". The Wire. Archived from the original on 25 March 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d Joshi, Sandeep; Kumar, Ashok (9 February 2013). "Afzal Guru hanged in secrecy, buried in Tihar Jail". The Hindu Times. Chennai, India. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ^ IANS (11 February 2013). "Two days after hanging, speed post reaches Afzal Guru's family". Times of India. Archived from the original on 11 February 2013. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- ^ a b c Buncombe, Andrew (9 February 2013). "Curfew imposed after India hangs Kashmiri man for 2001 attack on Parliament". The Independent (UK). London. Archived from the original on 27 February 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ^ a b "Afzal Guru hanging: SAR Geelani taken into preventive custody by Delhi Police". IBNLive. 9 February 2013. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ^ a b "Afzal's hanging politically motivated gimmick: SAR Geelani". ANI News. 9 February 2013. Archived from the original on 11 June 2015. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ^ Pandit, M Saleem (9 February 2013). "Afzal Guru hanged: Curfew imposed in Kashmir valley, NH closed to avert trouble". Times of India. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ^ a b Williams, Matthias (9 February 2013). "Protests erupt as Afzal Guru executed for 2001 parliament attack". Reuters. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ^ "Kashmir Newz Picture / 290906". Kashmirnewz.com. 29 September 2006. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- ^ a b Pandit, M Saleem (10 February 2013). "Curfew imposed across Kashmir to prevent protests". The Times of India. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ^ a b Ahmad, Marouf (10 February 2013). "Anti-India protests held despite strict curfew". Kashmirreader.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2013. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ "Scuffle in Delhi over Afzal Gurus hanging". The Times of India.[dead link]

- ^ "Protests against Afzal Guru's hanging at Jantar Mantar, 21 detained". Indian Express. 9 February 2013. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- ^ Nair, Harish V (9 February 2013). "Afzal Guru's hanging a political move: judge who sentenced him". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 10 February 2013. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ "Amnesty International | India: New execution points to worrying and regressive trend". Amnesty.org. 9 February 2013. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ PTI news agency (17 April 2013). "In Pakistan-Occupied Kashmir, Asif Ali Zardari attacks Afzal Guru execution". NDTV. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ PTI (9 February 2013). "Afzal Guru's hanging: Political parties say justice done – The Economic Times". Economictimes.indiatimes.com. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ "Public opinion forced Afzal Guru's hanging: BJP". Deccanherald.com. 9 February 2013. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ a b c PTI (9 February 2013). "Afzal Guru hanging: voice of affirmation across political spectrum". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ Dasgupta, Manas (18 February 2012). "Centre out to violate federal structure: Modi". The Hindu. Chennai, India.

- ^ "Guru's execution: AJK announces three-day mourning". The News (Pakistan). 9 February 2013. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ "Omar Abdullah aligns with Kashmiri sentiment – Economic Times". The Economic Times. 11 February 2013. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ^ a b "Afzal Guru's case was different, says Shinde". Deccan Herald. 11 February 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ a b Swami, Praveen (11 February 2013). "The vanity of 13/12 'truth-telling'". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ^ a b "Conspiracy theory: Was due process flouted to deny Guru a bid to escape hangman?". The Times of India. 10 February 2013. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ^ "No politics please: Afzal Guru's execution must be seen through a legal prism alone". The Times of India. 11 February 2013. Archived from the original on 11 April 2013. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ^ "India hangs Afzal Guru - Newspaper". Dawn.Com. 10 February 2013. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- ^ "Parliament attack victims' kin to write to Pranab". Daily News (USA). New York. 9 February 2013. Archived from the original on 11 April 2013. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ^ "Afzal Guru hanging: Two days later, speed post reaches family - India - DNA". Dnaindia.com. 11 February 2013. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ "Two days after hanging, speed post reaches Afzal Guru's family". The Shillong Times. 12 February 2013. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ "Afzal Guru's family was informed about the hanging decision on time: Shinde". Zee News. 11 February 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ "Afzal Guru's execution was done as per law: Sushilkumar Shinde". Zee News. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ "Lawyers of Afzal Guru's family withdraw". Deccan Herald. 13 February 2013. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ^ "Citing Delhi prison manual, Centre to reject Guru family's plea for his body". The Indian Express. 15 February 2013. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ^ Ishfaq-ul-Hassan (18 September 2013), "Afzal Guru`s book stirs up a hornet’s nest in Jammu and Kashmir", ZeeNews. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- ^ Muzamil Jaleel (18 February 2017), "Afzal Guru and the Jaish’s jihad project", IndianExpress. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- ^ Bilal Handoo (29 March 2018), "The untold Afzal Guru story", Kashmir Narrator. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- ^ Haksar, Nandita (2007). Framing Geelani, hanging Afzal: patriotism in the time of terror. New Delhi: Promilla & Co., Publishers in association with Bibliophile South Asia. ISBN 978-81-85002-80-4. OCLC 167765033.

- ^ The Afzal petition : a quest for justice. Champa: the Amiya & B.G. Rao Foundation. New Delhi: Promilla & Co. Publishers in association with Bibliophile South Asia and Champa. 2007. ISBN 978-81-85002-83-5. OCLC 181424377.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Qayyūm, Shabnam (2013). Phānsī : murattabah (in Urdu). Vaqār Pablīkeshanz. OCLC 889002448.

- ^ Roy, Arundhati (2013). The hanging of Afzal Guru : and the strange case of the attack on the Indian parliament. New Delhi: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-342075-0. OCLC 835036171.

External links[edit]

- Vinod K. Jose, "Mulakat Afzal: The first interview Mohammad Afzal gave from inside Tihar jail, in 2006" (an interview translated and widely reprinted between 2006 and 2013)

- "Delhi High Court – State vs Mohd. Afzal And Ors". Indian Kanoon. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- Supreme Court judgement on Afzal Guru Archived 20 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Bitta urges President not to pardon Afzal

- Clemency-seekers weakened Afzal's defence

- Terror needs direct response (Opinion)

- Life history of Afzal Guru (Hindi-language source)

- 1969 births

- 2013 deaths

- 21st-century executions by India

- Human rights abuses in India

- Executed Indian people

- Indian people convicted of murder

- Islamic terrorism in India

- Kashmiri militants

- Murder trials

- People convicted of murder by India

- People executed by India by hanging

- Kashmiri Islamists

- Inmates of Tihar Jail

- Indian people imprisoned on charges of terrorism

- People convicted on terrorism charges

- Executed mass murderers