Brachylophosaurus

| Brachylophosaurus Temporal range: Late Cretaceous,

| |

|---|---|

| |

| The mummified specimen "Leonardo" in The Children's Museum of Indianapolis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Clade: | †Ornithopoda |

| Family: | †Hadrosauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Saurolophinae |

| Tribe: | †Brachylophosaurini |

| Genus: | †Brachylophosaurus Sternberg, 1953 |

| Type species | |

| †Brachylophosaurus canadensis Sternberg, 1953

| |

| Synonyms | |

Brachylophosaurus (/brəˌkɪləfəˈsɔːrəs/ brə-KIL-ə-fə-SOR-əs or /ˌbrækiˌloʊfəˈsɔːrəs/ brak-i-LOH-fə-SOR-əs; meaning "short-crested lizard", Greek brachys = short + lophos = crest + sauros = lizard, referring to its small crest) was a mid-sized member of the hadrosaurid family of dinosaurs. It is known from several skeletons and bonebed material from the Judith River Formation of Montana, the Wahweap Formation of Utah and the Oldman Formation of Alberta,[1] living about 81-76.7 million years ago.[2]

Discovery and later finds[edit]

Brachylophosaurus was first named and described by Charles Mortram Sternberg in 1953 for a skull and partial skeleton, holotype NMC 8893, which he had found in 1936 near Steveville in Alberta, and which was at first thought to belong to Gryposaurus (or Kritosaurus as it was known at the time). The type species is Brachylophosaurus canadensis. The generic name is derived from Greek βραχύς, brachys, "short", and λόφος, lophos, "crest of a helmet". The specific name refers to the provenance from Canada.[3] Later, it was recognised that specimen FMNH PR 862, a partial skull discovered in 1922, could also be referred to B. canadensis. The type specimen was uncovered in a layer of the middle Oldman Formation dating from about 78 million years ago.[2]

The holotype remained the only described and recognised specimen of the genus until the 1980s, when Jack Horner described a second species, Brachylophosaurus goodwini, in 1988. The specific name honours preparator and collector Mark Goodwin. This species was based on a partial skull and skeleton, specimen UCMP 130139 found in the Judith River Formation of Montana, at the Skull Crest.[4] However, in 2005 a study by Albert Prieto-Márquez concluded that the perceived differences between the two species were either due to individual variation or the result of UCMP 130139 having been reconstructed with an upside down skull crest. B. goodwini would have been a junior synonym of B. canadensis.[5]

A further Canadian find was specimen TMP 1990.104.0001, a partial skeleton with skull in 1990 discovered at Milk River in Alberta and collected by Tyrrell staffer Darren Tanke and crew. Brachylophosaurus has subsequently become better known from fossils found in Montana than Alberta, however, despite its specific name canadensis. These include specimens MOR 720, a braincase; MOR 794, a very complete skeleton with skull of an adult individual; and MOR 940, another braincase. Near Malta, Montana an entire bonebed of Brachylophosaurus fossils has been uncovered containing over eight hundred specimens, that have been catalogued under number MOR 1071.[2]

In 1994 at Malta in Phillips County, amateur paleontologist Daniel Stephenson discovered a complete and uncrushed Brachylophosaurus skeleton which he nicknamed "Elvis".[6] Subsequently, even more informative finds were made by Murphy and his team from the Judith River Dinosaur Institute. On 20 July 2000, specimen JRF 115H or "Leonardo", a fully articulated and partially "mummified" skeleton of a subadult Brachylophosaurus, was discovered by Dan Stephenson.[7][8] It is considered one of the most spectacular dinosaur finds ever, and was included in the Guinness Book of World Records.[9] They subsequently excavated "Roberta", an almost complete gracile skeleton, and "Peanut", a partially preserved juvenile with some skin impressions. "Peanut" was discovered in 2002 by Robert E. Buresh and is on display at the Institute in Malta, MT.[10] In May 2008, Steven Cowan, public-relations coordinator at the Houston Museum of Natural Science, discovered a Brachylophosaurus skeleton subsequently dubbed "Marco" from the same area as Leonardo.[11]

Description[edit]

Size and general build[edit]

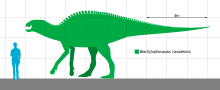

Brachylophosaurus is notable for its bony crest, which forms a horizontally flat, paddle-like plate over the top of the rear skull.[12] Some, depending on their age, had crests that covered nearly the entire skull roof, while others had shorter, narrower crests.[5] Some researchers suggest it was used for pushing contests,[13][14] but it may not have been strong enough for this. Other notable features are a relatively small head, the unusually long lower arms and the beak of the upper jaw being wider than other hadrosaurs of that time.[12]

Apart from the above, Brachylophosaurus was a typical hadrosaur which reached an adult length of at least 9 metres (30 ft).[12] In 2010, Gregory S. Paul estimated maximum length at 11 metres (36 ft) resulting in weight of 7 metric tons (7.7 short tons).[15] Like other hadrosaurs, Brachylophosaurus had features like cheeks to keep fodder in the mouth and dental batteries with hundreds of stacked teeth.[12] These teeth could be used to chew efficiently,[12] a feature rare among reptiles, but common among some cerapodan ornithischian dinosaurs like Brachylophosaurus.

Distinguishing traits[edit]

In 2015, Jack Horner established some distinguishing traits. Two of these are autapomorphies, unique derived characters. The crest formed by the nasal bones is flat and paddle-shaped in adult individuals and largely or totally overhangs the supratemporal fenestrae. The rear edge of the prefrontal bone overgrowths the frontal bone and more to the rear is oriented inwards and downwards to support the base of the crest and contribute to the edge of the supratemporal fenestra. Additionally, there is one trait that is not unique in itself but forms a unique combination with the two autapomorphies: the front branch of the lacrimal bone is extremely elongated and with its tip only touches the maxillary bone.[2]

Skeleton[edit]

The head of Brachylophosaurus is elongated. It is wide at the rear and very narrow along most of the length of the snout. The upper beak however, abruptly widens at its rear edge, forming a broad bone core for a horn sheath. The nostrils are extremely large and between them the nasal bones form a narrow tall bone wall on top of much of the snout. More to behind the nasal bones stretch out horizontally, creating a flat tongue-shaped skull crest that overgrowths and ultimately overhangs, most of the skull roof. The crest is not hollow but consists of massive bone. The crest has a low longitudinal ridge on the midline.

The maxilla, the tooth-bearing upper jaw bone, is rather elongated in front. Its tooth positions increase during the lifetime of the animal, ranging from thirty-three in younger individuals to forty-eight in the holotype specimen. The teeth are stacked in a tooth battery, with up to three teeth per position. The battery forms a sharp cutting edge, bending inwards, with one or sometimes two teeth per position contributing to the attrition surface. More to behind, the lower jugal bones and quadrate bones flare out sidewards, so that the skull is much wider at its rear lower edges than at the top surface, resulting in a trapezium-shaped profile in posterior view.

Soft tissues[edit]

Several so-called "mummies" provide information about the soft tissues of Brachylophosaurus. These "mummies" actually consist of natural casts formed in moulds in the stone matrix surrounding the skeleton, preserving the outline of the body and showing skin imprints. The best studied "mummy" has been "Leonardo", a specimen 90% of the cast surface of which is covered by imprints. Generally, the surface is close to the bones, which could be caused by desiccation before burial or the compressive action of the covering sediment. An exception is the region around the right shoulder, which shows the profile of about six centimetres thick muscles. "Leonardo" also indicates that the base of the neck was heavily muscled and that the soft tissue upper neck profile was placed in an elevated position, running much higher than was usually reconstructed in drawings which tended to follow the curvature of the vertebral column, and filling much of the bend between the front back and the head.[7]

On the snout, the remains of a broad keratinous beak are visible. The skin impressions show many folds and a structure of small polygonal scales. On the back a midline frill formed by triangular or hatchet-shaped projections is present. These seem to be individually separated and are placed as extensions of each neural spine of the vertebral column. The second, third and fourth finger of the hand are contained in a shared soft tissue "mitten".[7]

Examination of the stomach of "Leonardo" also reveals that the dinosaur was parasitized by small, needle-like worms covered in fine bristles. The discovery indicates that other dinosaur species might have been hosts of similar parasites.[16]

Classification[edit]

The following cladogram of hadrosaurid relationships was published in 2013 by Alberto Prieto-Márquez et al.:[17]

| Saurolophinae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology[edit]

In 2003, evidence of tumors, including hemangiomas, desmoplastic fibroma, metastatic cancer, and osteoblastoma was discovered in fossilized Brachylophosaurus skeletons. Rothschild et al. tested dinosaur vertebrae for tumors using computerized tomography and fluoroscope screening. Several other hadrosaurids, including Edmontosaurus, Gilmoreosaurus, and Bactrosaurus, also tested positive. Although more than 10,000 fossils were examined in this manner, the tumors were limited to Brachylophosaurus and closely related genera. The tumors may have been caused by environmental factors or genetic propensity.[18]

Diet[edit]

A 2008 study conducted on the famous dinosaur mummy Leonardo found that Brachylophosaurus had a diet that consisted of leaves, conifers, ferns, and flowering plants like magnolias. The study also found that Brachylophosaurus was a generalist herbivore; being both a browser and a grazer, but it did more of the former rather than the latter due to the contents found in its stomach.[19][20][21][22][23][24][25]

Paleoecology[edit]

Some of the less common hadrosaurs in the Dinosaur Park Formation of Dinosaur Provincial Park like Brachylophosaurus may represent the remains of individuals who died while migrating through the region.[26] They might also have had a more upland habitat where they may have nested or fed.[26]

See also[edit]

Most Closely Related animals

References[edit]

- ^ Horner, John R.; Weishampel, David B.; Forster, Catherine A. (2004). "Hadrosauridae". In Weishampel, David B.; Osmólska, Halszka; Dodson, Peter (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 438–463. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

- ^ a b c d Fowler, Elizabeth A. Freedman, and John R. Horner. "A New Brachylophosaurin Hadrosaur (Dinosauria: Ornithischia) with an Intermediate Nasal Crest from the Campanian Judith River Formation of Northcentral Montana." PLOS One 10.11 (2015): e0141304.

- ^ Sternberg, Charles M. (1953). "A new hadrosaur from the Oldman Formation of Alberta: Discussion of nomenclature". Canadian Department of Resource Development Bulletin. 128: 1–12.

- ^ Horner, John R. (1988). "A new hadrosaur (Reptilia, Ornithischia) from the Upper Cretaceous Judith River Formation of Montana". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 8 (3): 314–321. doi:10.1080/02724634.1988.10011714.

- ^ a b Prieto-Marquez, Alberto (2005). "New information on the cranium of Brachylophosaurus, with a revision of its phylogenetic position". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 25 (1): 144–156. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0144:NIOTCO]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 85767827.

- ^ "Brachylophosaurus dinosaur discovery". Judith River Dinosaur Institute. 2002. Archived from the original on 2008-09-08. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- ^ a b c Murphy, Nate L.; Trexler, David; Thompson, Mark (2006). ""Leonardo," a mummified Brachylophosaurus from the Judith River Formation". In Carpenter, Kenneth (ed.). Horns and Beaks: Ceratopsian and Ornithopod Dinosaurs. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 117–133. ISBN 0-253-34817-X.

- ^ "Dear Mummy: Rare fossil reveals common dinosaur's soft tissue: Science News Online". 2002-10-19. Archived from the original on 2007-01-14. Retrieved 2007-07-06.

- ^ "Brachylophosaurus dinosaur discovery". Judith River Dinosaur Institute. 2002. Archived from the original on 2008-05-18. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- ^ Newhouse, Eric (2008-06-01). "Malta dinosaur museum read to roar". Great Falls Tribune. Retrieved 2008-07-13. [dead link]

- ^ Newhouse, Eric (2008-06-02). "Badlands yield another impressive fossil". Great Falls Tribune. Archived from the original on 2008-06-03. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- ^ a b c d e "Brachylophosaurus." In: Dodson, Peter & Britt, Brooks & Carpenter, Kenneth & Forster, Catherine A. & Gillette, David D. & Norell, Mark A. & Olshevsky, George & Parrish, J. Michael & Weishampel, David B. The Age of Dinosaurs. Publications International, LTD. p. 134. ISBN 0-7853-0443-6.

- ^ Hopson, James A. (1975). "The evolution of cranial display structures in hadrosaurian dinosaurs". Paleobiology. 1 (1): 21–43. doi:10.1017/S0094837300002165. S2CID 88689241.

- ^ Weishampel, David B.; Horner, Jack R. (1990). "Hadrosauridae". In Weishampel, David B.; Osmólska, Halszka; Dodson, Peter (eds.). The Dinosauria (1st ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 534–561. ISBN 0-520-06727-4.

- ^ Paul, G.S., 2010, The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs, Princeton University Press p. 304

- ^ "Parasites wormed way into dino's gut". Archived from the original on 2016-07-02. Retrieved 2016-06-29.

- ^ Prieto-Márquez, A.; Wagner, J.R. (2013). "A new species of saurolophine hadrosaurid dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of the Pacific coast of North America". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 58 (2): 255–268. doi:10.4202/app.2011.0049.

- ^ Rothschild, B.M.; Tanke, D.H.; Helbling II, M.; Martin, L.D. (2003). "Epidemiologic study of tumors in dinosaurs" (PDF). Naturwissenschaften. 90 (11): 495–500. Bibcode:2003NW.....90..495R. doi:10.1007/s00114-003-0473-9. PMID 14610645. S2CID 13247222.

- ^ Tweet, Tweet, Justin S.; Chin, Karen; Braman, Dennis R.; Murphy, Nate L. (2008). "Probable gut contents within a specimen of Brachylophosaurus canadensis (Dinosauria: Hadrosauridae) from the Upper Cretaceous Judith River Formation of Montana". PALAIOS. 23 (9/10): 624–635. Bibcode:2008Palai..23..624T. doi:10.2110/palo.2007.p07-044r. S2CID 131393649.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lloyd, Robin (2008-09-25). "Plant-eating dinosaur spills his guts: Fossil suggests hadrosaur's last meal included lots of well-chewed leaves". NBC News. Retrieved 2009-07-03.

- ^ Walley, Mike. "Contents of a Dinosaur's Stomach – Eats, Shoots and Leaves (apologies to Lynne Truss)". Everything Dinosaur: Discover Everything. Retrieved 25 September 2008.

- ^ Hecht, Jeff. "Perfectly preserved dinosaur stuns palaeontologists". NewScientist. New Scientist Ltd. Retrieved 19 October 2002.

- ^ Stokstad, Erik. "Dinosaur 'Mummy' Unveiled". Science Magazine. merican Association for the Advancement of Science. Retrieved 18 October 2002.

- ^ Mayell, Hillary (18 July 2006). ""Mummified" Dinosaur Discovered In Montana". Biology Online. Biology Online. Retrieved 18 July 2006.

- ^ "Rare, Mummified Dinosaur Moves into New Home at The Children's Museum of Indianapolis". CISION PRWeb. PRWeb. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- ^ a b Tanke, D.H. and Brett-Surman, M.K. 2001. Evidence of Hatchling and Nestling-Size Hadrosaurs (Reptilia:Ornithischia) from Dinosaur Provincial Park (Dinosaur Park Formation: Campanian), Alberta, Canada. pp. 206-218. In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life—New Research Inspired by the Paleontology of Philip J. Currie. Edited by D.H. Tanke and K. Carpenter. Indiana University Press: Bloomington. xviii + 577 pp.

External links[edit]

- The Judith River Dinosaur Institute

- Brachylophosaurus from SkeletalDrawing.com