Communipaw

Communipaw, Jersey City | |

|---|---|

| Coordinates: 40°42′31″N 74°03′40″W / 40.70861°N 74.06111°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | |

| County | Hudson |

| City | Jersey City |

| Elevation | 20 ft (6 m) |

| GNIS feature ID | 875597[1] |

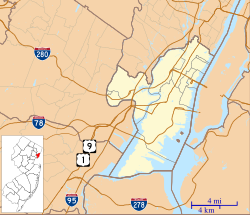

Communipaw is a neighborhood in Jersey City in Hudson County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey.[2] It is located west of Liberty State Park and east of Bergen Hill,[3][4] and the site of one of the earliest European settlements in North America. It gives its name to the historic avenue which runs from its eastern end near Liberty State Park Station through the neighborhoods of Bergen-Lafayette and the West Side that then becomes the Lincoln Highway. Communipaw Junction, or simply The Junction, is an intersection where Communipaw, Summit Avenue, Garfield Avenue, and Grand Street meet, and where the toll house for the Bergen Point Plank Road was situated. Communipaw Cove at Upper New York Bay, is part of the 36-acre (150,000 m2) state nature preserve in the park and one of the few remaining tidal salt marshes in the Hudson River estuary.

Communipaw-Lafayette[edit]

Communipaw was part of Bergen City, New Jersey between 1855-1870 before merging with Jersey City, and was urbanized during the late half of the 19th century. Some streets of the neighborhood are part of the Communipaw-Lafayette Historic District.[5] Lafayette Park is likely named for the Marquis de Lafayette, who was stationed in Bergen in 1799,[6] and later re-visited in 1824.[7][8][9] It is a city square, similar to Van Vorst Park and Hamilton Park; the buildings surrounding it were constructed in different periods. Whitlock Cordage[10] is an intact complex of industrial buildings built in the Lafayette section along the long ago filled Morris Canal.[11][12] The Housing Trust of America purchased the property to preserve the structures as affordable housing. The section near Johnston Avenue was the site of a stop on the Underground Railroad and African-American burial ground.[13] Ficken's Warehouse, once the site of Bergen City's main post office, is on the National Register of Historic Places listings in Hudson County, New Jersey. Berry Lane Park was formerly an industrial area.

History[edit]

| New Netherland series |

|---|

| Exploration |

| Fortifications: |

| Settlements: |

| The Patroon System |

|

| People of New Netherland |

| Flushing Remonstrance |

|

Lenape[edit]

At the time of European settlement in the 17th century, Communipaw was the site of the summer encampment and council fire of the Hackensack Indians,[14] a phratry of the Lenape. They, along with the Raritan, Tappan, Wecquaesgeek, Canarsee and other groups who circulated in the region were collectively known as the River Indians by the immigrating population.

It is likely that the name is based in the Algonquian language Lenape. Earlier spellings are numerous and have included Gamoenapa,[14] Gemonepan,[15] Gemoenepaen,[15] Gamenepaw, Comounepaw, Comounepan[16] Communipau,[17] Goneuipan[18] There are a variety of interpretations of the meaning, though most sources relate it to being from gamunk, "on the other side of the river", and pe-auke, "water-land", meaning "big landing-place from the other side of the river".[19] (Current: "gamuck" meaning "other side of the water" or "otherside of the river"[20] or "landing place at the side of a river"[21]).

New Netherland[edit]

Henry Hudson, commissioned by the Dutch East India Company, anchored along the shore at Communipaw in 1609 during his explorations of the Upper New York Bay, North River (Hudson River) and Hudson Valley. [22] On September 12 he sailed up to Communipaw, where Robert Juet, his mate, wrote in the log that it was "...a very good land to fall in with, and a pleasant land to see."[23] In 1634 one of the first "bouweries", or homesteads, in the colony of New Netherland was built at Communipaw as part of Pavonia, a patroonship of Amsterdam businessman Michael Pauw. (Some have suggested that the name comes from Community of Pauw, which likely is more a coincidence than a fact.[24][25][26][27]) For a time it bore the name of the Dutchman who settled there, Jan Everts Bout,[28] and was called Jan de Lacher's Hoeck,[29] or "Jan the Laugher's Point", apparently in reference to his boisterous character. Plantations, worked by enslaved Africans, spread across the low-lying areas between the shoreline and the hill.[30] It was here that Tappan and Wecquaesgeek fleeing dominant tribes from the north had taken refuge in 1643. They were attacked in the incident known as the Pavonia Massacre, subsequently leading to Kieft's War.[31]

Originally the village of Communipaw was part of the colony under the jurisdiction of the Dutch West India Company. In 1653 it became part of the Commonality of New Amsterdam,[32] which included all the settlements at Pavonia, Manhattan, Staten Island, and Long Island). It became a separate village in 1658,[33][34][35] under the jurisdiction of Bergen, established at contemporary Bergen Square. By 1669, regulated ferry service to New Amsterdam had been established.[36][37] After the last English takeover of New Netherland in 1674 it became part of the Province of New Jersey, in the county of Bergen, though it retained its Dutch character for hundreds of years. Washington Irving visited it often (at least once with future US president Martin van Buren) for inspiration. Writing in the early 19th century, he often referred to Communipaw as being the stronghold of traditional Dutch culture.[38]; he refers to it in The Legend of Sleepy Hollow. James Fenimore Cooper's The Water-Witch and Herman Melville's The Confidence-Man both mention Communipaw as stronghold in a similar vein. John Quidor, an American Romantic painter, created works inspired the village: Embarkation from Communipaw and The Voyage from Communipaw to Hell Gate. Suydam Street, which can be translated as "south dam", runs for one block south of Communipaw Avenue is taken early Dutch family, whose descendant, Rev. J. Howard Suydam, D.D, was member and historian of the Holland Society of New York.[39]

Railroads[edit]

Originally, the waters of the Upper New York Bay facing the village (situated near the site of today's Liberty Science Center) hosted vast oyster beds that were harvested well into the 19th century.[40] As it was industrialized, first with the construction of ports and later with rail infrastructure, the shoreline was expanded with landfill, notably by the Lehigh Valley Railroad and the Central Railroad of New Jersey. Communipaw Terminal, officially known as the Central Railroad of New Jersey Terminal, was the waterfront terminus. The cove just to the south of the station is sometimes still called Communipaw Cove. The railroad also maintained a Communipaw Station in the neighborhood farther inland along the right of way now used by the Hudson Bergen Light Rail. Johnston Avenue is named for an early president of the company.

Transportation[edit]

Buses traveling southbound through The Junction are New Jersey Transit routes 6,[41] and 81[42] through Greenville to Curries Woods, with the 81 continuing to Bayonne. On some trips the 6 alternates its routes along the Lafayette Loop. Northbound the 6 travels to Journal Square, while the 81 travel through Downtown Jersey City to Exchange Place. The nearest stations of the Hudson Bergen Light Rail are located along the southern periphery of the neighborhood at Garfield Avenue in Claremont neighborhood and at Liberty State Park.

See also[edit]

- Communipaw Ferry

- Bergen

- Achter Kol

- Harsimus

- Pavonia

- Vriessendael

- English Neighborhood

- List of neighborhoods in Jersey City, New Jersey

- Etymologies of place names in Hudson County, New Jersey

References[edit]

- ^ a b "Communipaw". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ Locality Search, State of New Jersey. Accessed February 7, 2015.

- ^ "· HC areas map" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 27, 2011. Retrieved August 25, 2009.

- ^ http://www.geody.com/geospot.php?world=terra&ufi=100875597&alc=cmm Map

- ^ NJ State Register of Historic Places in Hudson County Archived July 5, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Battle with British

- ^ Aplple Tree House

- ^ Harriet Phillips Eaton, Jersey City And Its Historic Sites, 1899:

- ^ Grundy, J. Owen (1975). The History of Jersey City (1609 - 1976). Jersey City: Walter E. Knight; Progress Printing Company.

- ^ "Jersey City History: The Whitlock Cordage". The Jersey City Landmarks Conservancy. 2007. Retrieved June 24, 2009. [dead link]

- ^ "In Bergen-Lafayette, a canal runs through it - The Real Deal".

- ^ JC Online

- ^ Underground Railroad in JC

- ^ a b Edward Manning Ruttenber (July 1, 1992). Indian Tribes of Hudson's River: To 1700. North Country Books. ISBN 978-0-910746-98-4.

- ^ a b Joan Doherty Lovero (March 1986). Hudson County: The Left Bank. Windsor Publications. ISBN 978-0-89781-172-9.

- ^ New Jersey Colonial Records, East Jersey Records: Part 1-Volume 21, Calendar of Records 1664-1702

- ^ "Jersey City History - Old Bergen - Chapter XV".

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 27, 2009. Retrieved November 1, 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ https://archive.org/stream/fourchaptersofpa00shri/fourchaptersofpa00shri_djvu.txt [bare URL plain text file]

- ^ The Lenape/English Dictionary http://www.gilwell.com/lenape

- ^ http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~njmorris/general_info/indian.htm [user-generated source]

- ^ "History of Jersey City New Jersey".

- ^ http://www.jerseycityonline.com/history_of_jersey_city.htm JC Online]

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on May 9, 2012. Retrieved November 4, 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ http://familytreemaker.genealogy.com/users/m/y/e/Ron-C-Myers/GENE31-0099.html[user-generated source]

- ^ Gannett, Ganett, Henry, The Origin of Certain Place Names in The United States

- ^ Writers' Program (U.S.) New Jersey. The Origin of New Jersey Place Names Trenton , NJ, New Jersey Public Library Commission, 1945. ... www.njstatelib.org/NJ_Information/Digital_Collections/Digidox7.php

- ^ "Jan Evertsen Bout at Pavonia". Archived from the original on September 4, 2017. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ "Communipaw". Archived from the original on June 4, 2016. Retrieved November 4, 2008.

- ^ Hodges, Graham Rusell (1999). "Free People and Slaves, 1613-1664". Dutch New York:Roots and Branch:African Americans in New York and East Jersey. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. p. 9. ISBN 0-8078-4778-X.

- ^ "Jan Evertszen Bout". Archived from the original on September 4, 2017. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ Russell Shorto (April 12, 2005). The Island at the Center of the World: The Epic Story of Dutch Manhattan and the Forgotten Colony that Shaped America. Random House. ISBN 1-4000-7867-9.

- ^ "Register of New Netherland, Annals of New Netherland". Archived from the original on October 17, 2008. Retrieved December 14, 2008.

- ^ JC History

- ^ "The Project Gutenberg eBook of Journal of Jasper Danckaerts, 1679-1680, by Jasper Danckaerts".

- ^ Arthur G. Adams (April 1, 1996). The Hudson River Through the Years. Fordham University Press. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-8232-1677-2.

- ^ william a. whitehead (1856). contributions to the early history of perth amboy. D. Appleton & Company. p. 272.

- ^ http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Knickerbocker%27s_History_of_New_York/Book_II/Chapter_II

- ^ Vookles, Laura (June 12, 2009). Roger Panetta (ed.). Dutch New York The Roots of Hudson Valley Culture. Yonkers, New York: Hudson River Museum. pp. 275, 279. ISBN 978-0-8232-3039-6.

- ^ Mark Kurlansky (January 9, 2007). The Big Oyster: History on the Half Shell. Random House Trade Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-345-47639-5.

- ^ "NJT bus 6 schedule" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 28, 2018. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- ^ "NJT 81 schedule" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 4, 2009. Retrieved March 16, 2010.