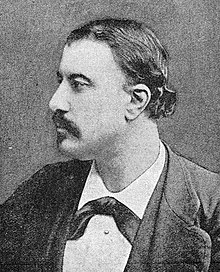

Frederic Clay

Frederic Emes Clay (3 August 1838 – 24 November 1889) was an English composer known principally for songs and his music written for the stage. Although from a musical family, for 16 years Clay made his living as a civil servant in HM Treasury, composing in his spare time, until a legacy in 1873 enabled him to become a full-time composer. He had his first big stage success with Ages Ago (1869), a short comic opera with a libretto by W. S. Gilbert, for the small Gallery of Illustration; it ran well and was repeatedly revived. Clay, a great friend of his fellow composer Arthur Sullivan, introduced the latter to Gilbert, leading to the Gilbert and Sullivan partnership.

In addition to Gilbert, Clay's librettists during his 24-year career included B. C. Stephenson, Tom Taylor, T. W. Robertson, Robert Reece and G. R. Sims. The last of his four pieces with Gilbert was Princess Toto (1875), which had short runs in the West End and in New York. Clay's other compositions include cantatas and numerous individual songs. His last two works were both successful operas composed in 1883, The Merry Duchess and The Golden Ring. He then suffered a stroke that paralysed him at the age of 44 and ended his career.

The historian Kurt Gänzl has called Clay "the first significant composer of the modern era of British musical theatre",[1] but even his most successful stage works were soon eclipsed by those of Gilbert and Sullivan. During his lifetime he was best known for his parlour songs, which were familiar throughout Britain. Clay's music was widely regarded as not particularly original or memorable, but musicianly and pleasing.

Life and career[edit]

Early years[edit]

Clay was born in Paris, the fourth of six children of James Clay (1804–1873) and his wife, Eliza Camilla, née Woolrych.[2] James Clay was a Radical Member of Parliament and was also well known as a player of and authority on whist. Both parents were musical: Clay's mother was the daughter of a leading opera singer, and his father was an amateur composer.[2] Clay was educated at home in London by private tutors, and studied piano and violin, and later composition under Bernhard Molique.[3] Through the influence of Lord Palmerston, Clay secured a post in HM Treasury,[4] and was for a time private secretary to Benjamin Disraeli, who presented him at a court levee in 1859.[5] Under a later administration Clay undertook confidential missions on behalf of W. E. Gladstone.[6]

At the age of 20 Clay experienced what he called the "opening up" of his musical senses: hearing Verdi's Il trovatore at Covent Garden and Auber's Les diamants de la couronne at the Opéra-Comique in Paris, he was enthused by "the strength of vocal declamation in the one work and the delight of musical comedy in the other".[4] In his free time he studied music with Moritz Hauptmann in Leipzig, and composed what his biographer Christopher Knowles calls "songs and light operas for the drawing rooms of high society".[2] With his fellow Treasury clerk B. C. Stephenson as librettist he wrote three one-act operettas for amateurs: The Pirate's Isle (1859), Out of Sight (1860) and The Bold Recruit (1868).[4] The Era commented on the second of these: "The composer is an amateur, but he has shown a dramatic power and a skill in instrumentation that would justify him in entering the lists with professional musicians".[7]

Clay had a modest operatic success with a one-act operetta, Court and Cottage, to a libretto by Tom Taylor, produced at Covent Garden in 1862 as an after-piece to Meyerbeer's Dinorah.[8] A second one-act piece for Covent Garden followed in 1865: Constance, a curtain-raiser for the annual pantomime, had a libretto by T. W. Robertson.[9] Like Court and Cottage, it was favourably reviewed in the press,[10] but did not remain in the theatrical repertoire.[n 1]

In the mid-1860s, Clay and his close friend and fellow musician Arthur Sullivan were frequent guests at the home of John Scott Russell. By about 1865 Clay became engaged to Scott Russell's youngest daughter, Alice May, and Sullivan wooed the middle daughter, Rachel.[12] The Scott Russells welcomed the engagement of Alice and Clay, but it was broken off, for unknown reasons.[2][12][n 2] Alice married another suitor in 1869; Clay remained single all his life.[2][n 3]

1866 to 1873[edit]

In 1866 Clay's first cantata, The Knights of the Cross was performed in London, conducted by Sullivan. It was politely received, but the composer's "talent and good taste" did not, in the opinion of one reviewer, result in "much originality of character".[14][n 4] In 1869 came Clay's first substantial theatrical success, the "operatic entertainment" Ages Ago, written for the German Reeds at the Royal Gallery of Illustration, with a libretto by W. S. Gilbert.[n 5] The piece, described by the historian Kurt Gänzl as "an enormous success", ran for 350 performances during its first run, and was revived several times.[16] The first production was in a double bill with Sullivan's Cox and Box.[17] Clay dedicated the published score of Ages Ago to Sullivan;[18] at a rehearsal of the piece, probably in 1870, Gilbert met Sullivan for the first time, introduced by Clay.[19]

Over the next four years Clay composed four further operatic pieces. The first, The Gentleman in Black (1870, with Gilbert), contained many of the topsy-turvey ideas the librettist was to develop in his later collaborations with Sullivan and others.[20] The premiere was enthusiastically received – in a favourable review The Morning Post noted that almost every number was encored[21] – but the piece ran for only 26 performances.[20] The next three, In Possession (1871, for German Reed), Happy Arcadia (1872, with Gilbert), and Oriana (1873, with James Albery) all had short London runs.[22] Clay contributed some of the music for other London shows in these years, including the extravaganzas Ali Baba à la Mode (1872) and Don Giovanni in Venice (1873), the "grand opéra-bouffe féerie" The Black Crook (1872)[n 6] and the "fantastic music drama" Babil and Bijou, or The Lost Regalia (1872).[24] The last of these, given at Covent Garden was a spectacular production that ran for some eight months and attracted highly favourable notices for Clay and his fellow composer, Jules Rivière.[25]

Full-time composer[edit]

Foreseeing, and not relishing, a long period of Conservative government after the party's election victory in February 1874, Clay resigned from the Treasury.[4] A legacy from his father, who died in September 1873, left him financially independent and able to devote his energies to full-time composition.[4][n 7]

Green Old Age, a "musical improbability" to a libretto by Robert Reece (1874), was followed by a commission from Kate Santley for an opéra-bouffe. Cattarina, or Friends at Court, with a libretto by Reece, successfully toured the provinces, with the composer conducting and Santley starring as Pincione; it was given at the Charing Cross Theatre, London, during the winter season of 1874–75.[26]

The final collaboration between Clay and Gilbert was a three-act comic opera, Princess Toto, (1876), another vehicle for Santley.[24] On tour and in the West End it attracted mixed notices, both for the libretto and the score. The Times's later comment that the piece was "probably surpassed by no modern English work of the kind for gaiety and melodious charm"[27] was not generally shared: a recurring theme in reviews was that Clay's music was musicianly and pleasing but not strikingly original or memorable.[28] At its first London production Princess Toto ran for less than a month. A New York production fared still worse.[29] When it was revived in London in 1881 The Times commented that the piece had not appealed to audiences in 1876, "accustomed to a more broadly humorous style of extravaganza" and hoped that by 1881 public taste had become more cultivated under the influence of Gilbert's other comic operas.[30][n 8] Nonetheless, the revival ran for only 65 performances.[29][n 9]

Clay's cantata Lalla Rookh (containing his best-known song, "I'll sing thee songs of Araby" and also "Still this golden lull"), was given successfully at the Brighton Festival in 1877, and was later performed elsewhere in Britain and the US.[3] Clay found a lack of opportunity in Britain and moved to the US in 1877.[2] He met with only mixed success there and returned to London in 1881.[3] His last stage works were two collaborations with the librettist G. R. Sims: a "sporting comic opera", The Merry Duchess, (1883) given at the Royalty Theatre, starring Santley,[33] and The Golden Ring starring Marion Hood (1883). The latter was written for the reopening of the Alhambra Theatre, which had been burned to the ground the year before.[34] These shows were both successful and, in Gänzl's view, showed an artistic advance on Clay's earlier work.[35]

Clay had been in precarious health during the year, and had been obliged to abandon work on a third cantata, Sardanapalus, commissioned for the Leeds Festival.[36] After conducting the second performance of The Golden Ring in December 1883 he suffered a stroke that paralysed him and cut short his productive life.[2] In 1889 at the age of 51, he was found drowned in his bath at the home of his sisters in Great Marlow. The coroner's verdict was suicide while of unsound mind. Clay was buried in Brompton cemetery on 29 November 1889.[2]

Music[edit]

Sullivan wrote the article about his friend in the early editions of Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians. He said of Clay's music:

In the article in the 2001 edition of Grove, Christopher Knowles sums up Clay's music:

His melodies are always fresh and graceful; his harmonic treatment, though sometimes strikingly original, owes much to Rossini and Auber. Successful though he was, he never really broke away from the drawing-room ballad and, lacking Sullivan’s sense of fun and powers of invention, remained largely in his shadow.[3]

Although even his most successful stage works were soon eclipsed by those of Gilbert and Sullivan, and his music was widely regarded as musicianly and pleasing but not particularly original or memorable, in Gänzl's view he was "the first significant composer of the modern era of British musical theatre".[1]

Music theatre[edit]

| Title | Genre | Acts | Librettist | Premiered at | Premiered on | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Pirate's Isle | operetta | ? | B. C. Stephenson | Private amateur performance | 1859 | Score and libretto lost |

| Out of Sight | operetta | 1 | Stephenson | Bijou Theatre, London | February 1860 | |

| Court and Cottage | operetta | 1 | Tom Taylor | Covent Garden | 22 March 1862 | |

| Constance | opera | 1 | T. W. Robertson | Covent Garden | 23 January 1865 | |

| The Bold Recruit | operetta | 1 | Stephenson | Theatre Royal, Canterbury | 4 August 1868 | |

| Ages Ago | musical legend | 1 | W. S. Gilbert | Gallery of Illustration, London | 22 November 1869 | |

| The Gentleman in Black | musical legend | 2 | Gilbert | Charing Cross Theatre, London | 26 May 1870 | |

| In Possession | operetta | 1 | Robert Reece | Gallery of Illustration | 20 June 1871 | |

| Babil and Bijou, or The Lost Regalia | fantastic music drama | 5 | J. R. Planché after Dion Boucicault | Covent Garden | 29 August 1872 | Collaboration with Hervé. Jules Riviére and J-J. de Billemont |

| Ali Baba à la Mode | extravaganza | ? | Reece | Gaiety Theatre, London | 14 September 1872 | Collaboration with George Grossmith and others |

| Happy Arcadia | musical entertainment | 1 | Gilbert | Gallery of Illustration | 28 October 1872 | |

| The Black Crook | grand opéra-bouffe féerie | 4 | Harry Paulton and John Paulton after the Cogniard brothers' La Biche aux bois | Alhambra Theatre, London | 23 December 1872 | Collaboration with Georges Jacobi |

| Oriana | romantic legend | 3 | James Albery | Globe Theatre, London | 16 February 1873 | |

| Don Giovanni in Venice | extravaganza | ? | Reece | Gaiety | 18 February 1873 | Collaboration with James Molloy and Meyer Lutz |

| Don Juan | Christmas extravaganza | 7 scenes | H. J. Byron | Alhambra | 19 January 1874 | Collaboration with Jacobi. Other music by Lecocq and Offenbach |

| Cattarina, or Friends at Court | comic opera | 2 | Reece | Prince's Theatre, Manchester | 17 August 1874 | |

| Green Old Age | musical improbability | 1 | Reece | Vaudeville Theatre, London | 31 October 1874 | |

| Princess Toto | comic opera | 3 | Gilbert | Theatre Royal, Nottingham and later Strand Theatre, London | 26 June 1876 | |

| Don Quixote | grand comic and spectacular opera | 3 | H. Paulton and Alfred Maltby | Alhambra | 25 September 1876 | |

| The Black Crook | rev. version | 4 | Alhambra | 3 December 1881 | ||

| The Merry Duchess | sporting comic opera | 2 | G. R. Sims | Royalty Theatre, London | 23 April 1883 | |

| The Golden Ring | fairy opera | 3 | Sims | Alhambra | 3 December 1883 |

Incidental music[edit]

- Monsieur Jacques (1876)[38]

- The Squire (1881)[38]

- Twelfth Night[37]

Choral[edit]

- The Knights of the Cross (cantata, 1866)[38]

- The Red Cross Knight (London, 1871, revision of the 1866 work, above)[38]

- Lalla Rookh (cantata, Brighton Festival, 1877)[38]

Songs[edit]

Numerous, including "She Wandered Down the Mountainside", "The Sands of Dee", and "'Tis Better Not to Know".[38]

Notes, references and sources[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ According to a summary by Kurt Gänzl, "Constance was written to a rather 'heavy' libretto. ... It was a tale of love and patriotism set in Poland under the Russians – something of a Polish Tosca, but with a happy ending when the hero and heroine are rescued first by a singing vivandière and then by the Polish army. The music ... was noted as being promising if rather light and, after being performed eighteen times as a curtain-raiser … it sank into obscurity."[11]

- ^ The Scott Russells forbade the relationship between Sullivan and Rachel, because Sullivan had uncertain financial prospects, although Rachel continued to see him covertly.[12]

- ^ Alice married François Arthur Rausch at Lewisham in September 1869.[13]

- ^ In 1871 a revised version was presented under the title The Red Cross Knight. The composer conducted, with Sullivan at the organ, a choir of 200 and an orchestra of 80.[15]

- ^ Clay asked Robertson to write the libretto for the piece, but the latter was too busy and gave Clay an introduction to "a better man than I shall ever be", namely Gilbert.[4]

- ^ The opera shared a French plot source with the 1866 American musical The Black Crook but was otherwise unrelated.[23]

- ^ Like his friend Sullivan, Clay was an inveterate gambler, and he eventually lost the money his father left him and had to rely on his earnings from music.[4]

- ^ Between the 1876 and 1881 productions Gilbert and Sullivan had written The Sorcerer, H.M.S. Pinafore, The Pirates of Penzance and Patience.[31]

- ^ The revival was the first production at the Opera Comique after the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company moved from there to the Savoy Theatre during the run of Patience, which totalled 578 performances at the two theatres.[32]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Gänzl (2001), p. 389

- ^ a b c d e f g h Knowles, Christopher. "Clay, Frederic Emes (1838–1889)" Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004. Retrieved 6 February 2021

- ^ a b c d Knowles, Christopher. "Clay, Frederic" Archived 5 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, 2001. Retrieved 6 February 2021

- ^ a b c d e f g "Mr Frederic Clay at Clarence Chambers", The Yorkshire Post, 18 April 1883, p. 6

- ^ "Her Majesty's Levee", The Morning Chronicle, 12 May 1859, p. 5

- ^ "Death of Mr Frederic Clay", The Era, 30 November 1889, p. 9

- ^ "The Theatres", The Era, 14 July 1861, p. 10

- ^ "Royal English Opera", The Times, 24 March 1862, p. 12

- ^ "Royal English Opera", The Times, 24 January 1865, p. 9

- ^ "Royal English Opera", The Morning Post, 24 March 1862, p. 6; "Royal English Opera", The Standard, 24 March 1862, p. 3; "Music." The Daily News, 24 January 1865, p. 2; "Royal English Opera", The Standard, 24 January 1865, p. 3; and "Royal English Opera", The Times, 24 January 1865, p. 9

- ^ Gänzl (1986), p. 16

- ^ a b c Ainger, p. 87; Jacobs, p. 53

- ^ "Births, Marriages and Deaths", Pall Mall Gazette, 2 October 1869, p. 5

- ^ "Civil Service Musical Society", The Standard, 23 July 1866, p. 7

- ^ "Table Talk", The Musical Standard, 4 November 1871, p. 355

- ^ Gänzl (1986), p. 19 and (2001), p. 389

- ^ "Royal Gallery of Illustration", The Morning Post, 23 November 1869, p. 3

- ^ Searle, p. 21

- ^ Crowther, p. 84

- ^ a b Gänzl (2001), p. 758

- ^ "The Gentleman in Black", The Morning Post, 27 May 1870, p. 3

- ^ a b Knowles, p. 878

- ^ Gänzl (2001), p. 185

- ^ a b c Gänzl (2001), p. 390

- ^ Rivière, pp. 176–177

- ^ Gänzl (2001), p. 389; and "Advertisements and Notices", The Era, 27 June 1875, p. 12

- ^ Obituary, The Times, 29 November 1889, p. 5

- ^ "Theatre Royal", Birmingham Daily Post, 5 July 1876, p. 7; "Drama", The Daily News, 6 October 1876, p. 3; "The Strand", The Era, 8 October 1876, p. 13; "Standard Theatre", The New York Times, 14 December 1879, p. 7; and "The Drama in America", The Era, 11 January 1880, p. 4

- ^ a b Gänzl (2001), p. 1657

- ^ "Opera Comique", The Times, 18 October 1881, p. 4

- ^ Rollins and Witts, pp. 5–8

- ^ Rollins and Witts, p. 8

- ^ Gänzl (1986), p. 228

- ^ Gänzl (1986), p. 230

- ^ Gänzl (1986), pp. 228 and 230

- ^ Rivière, p. 220; and Jacobs, p. 184

- ^ a b Sullivan, p. 552

- ^ a b c d e f Slonimsky et al, pp. 657–658

Sources[edit]

- Ainger, Michael (2002). Gilbert and Sullivan – A Dual Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514769-8.

- Crowther, Andrew (2011). Gilbert of Gilbert & Sullivan. London: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-5589-1.

- Gänzl, Kurt (1986). The British Musical Theatre, Vol.1 1865–1914. Basingstoke: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-39839-5.

- Gänzl, Kurt (2001). The Encyclopedia of the Musical Theatre (second ed.). New York: Schirmer Books. ISBN 978-0-02-864970-2.

- Jacobs, Arthur (1984). Arthur Sullivan: A Victorian Musician. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-315443-8.

- Knowles, Christopher (1992). "Clay, Frederic". In Stanley Sadie (ed.). The New Grove Dictionary of Opera. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-48552-1.

- Rivière, Jules (1893). My Musical Life and Recollections. London: Sampson Low, Marston. OCLC 1028184155.

- Rollins, Cyril; R. John Witts (1962). The D'Oyly Carte Opera Company in Gilbert and Sullivan Operas: A Record of Productions, 1875–1961. London: Michael Joseph. OCLC 504581419.

- Searle, Townley (1968) [1931]. A Bibliography of Sir William Schwenck Gilbert. New York: Franklin. OCLC 1147707940.

- Slonimsky, Nicholas; Laura Kuhn; Dennis McIntire (2001). "Clay, Frederic". Baker's Biographical Dictionary of Musicians. New York: Schirmer. ISBN 978-0-02-865525-3.

- Sullivan, Arthur (1911) [1890]. "Clay, Frederic". In George Grove; J. A. Fuller Maitland (eds.). A Dictionary of Music and Musicians (second ed.). London: Macmillan. OCLC 86048631.

External links[edit]

- List of Clay works at The Guide to Light Opera & Operetta

- Free scores by Frederic Clay at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)