Ludovico Ottavio Burnacini

Lodovico Ottavio Burnacini[a] (1636 – 12 December 1707) was an Italian architect, and theatrical stage and costume designer, who served the imperial court in Vienna beginning in 1652. He is considered one of the most important "theater engineers" in Baroque Europe and is a master of drawing. His work as a stage designer for the lavish entertainments at the court of the Emperors Leopold I and Joseph I is preserved in numerous engravings[1] and in many drawings in the collections of the Theatermuseum in Vienna.

Life and work[edit]

Origins and birth[edit]

Lodovico Ottavio was the son of a certain 'Grazia' and the theater architect Giovanni Burnacini from Cesena, from whom he learned the arts of theater architecture, stage machinery and set design from a young age. His birthday and place of birth are still unknown.

With regard to his place of birth, recent research has not been able to confirm the references of early literature[2][3] to Mantua, which until now has been adopted by most lexica and reference works. As for the previously held assumption that Giovanni Burnacini might have received several commissions in Mantua, no archival documents or contemporaneous sources have been able to confirm this.

Since an intense and continuous period of artistic activity in the career of Giovanni Burnacini has been documented beginning in 1636 in Venice,[4] it seems plausible that Lodovico Ottavio was born in the lagoon city.

Education and Venetian influence[edit]

In the middle of the 17th century, Venice was one of the most important theater cities in Europe. Beginning in the 1640s, Lodovico Ottavio’s father Giovanni led renowned theater houses in Venice, such as the San Cassian, the Teatro Santi Giovanni e Paolo and the Teatro Santissimi Apostoli. Some early engravings based on Giovanni’s designs, such as the one entitled Trionfo del SS. Sacramento (Prague, 1652), prove the close cooperation between father and son fostered during Lodovico's childhood. Working in his father’s workshop, Lodovico Ottavio, from an early age, witnessed the theater world, observing the eager cooperation and collaboration of impresari, engineers, composers, musicians, actors etc.

It seems plausible that during his time in Venice Lodovico also had a chance to see the famous maschere (masks and disguises) of the Venetian carnival and to watch performances of the Italian comedians, which were very popular in the 17th century. In fact, numerous references in his graphic work—i.e. in his many drawings created decades later—indicate the importance of such experiences of his youth.[5]

Moving to Vienna in 1651[edit]

In 1651 Emperor Ferdinand III summoned Giovanni Burnacini to Vienna due to his artistic merits and he took the sixteen-year-old Lodovico Ottavio with him. A few months later, the entire family followed, and from then on they resided in Vienna.

The move of the Burnacini family to Vienna was presumably due to an invitation by Empress Eleonora Gonzaga-Nevers, who in the same year (1651) became the third wife of Emperor Ferdinand III and who made intensive contacts with the Venetian cultural scene.[4]

Between Vienna, Regensburg and Prague[edit]

From this point on, the Burnacinis were responsible for the design of festivals and the construction of theaters, including the invention of all the necessary decorations for the imperial court. At the imperial court theater, they introduced their own system of convertible stage sets made of canvas flats (backdrop stage), which had been tried and tested in Italy, and perfected it further. The most famous Burnacini stage works from this early period at the service of the Habsburgs include the tournament opera La gara by Alberto Vimina (Vienna, 1652) and L'inganno d'Amore by Benedetto Ferrari, which was held on March 3, 1653 in Regensburg on the occasion of the Reichstag (December 1652 – May 1654) and was premiered in a specially built, wooden theater house.[6] Various other works followed, sometimes for ephemeral buildings such as the Triumph of the Blessed Sacrament in Prague in 1652 and the Castrum Doloris for Archduke Ferdinand IV from 1654, of which exists a copperplate engraving in the collections of the Albertina in Vienna (inv. No. DG 2018/207).

The death of the father in 1655[edit]

After his father's untimely death on July 21, 1655, Lodovico Ottavio had to take over all responsibilities and take care of the entire family, consisting of five siblings. Nevertheless, after the government was taken over by Emperor Leopold I in 1657, Burnacini was not confirmed to his father's office. From July 1, 1657 the new monarch engaged Giovanni Battista Angelini († 1658), who had been the architect and stage designer of his uncle Archduke Leopold Wilhelm, during his governorship in Brussels.[7]

The imperial theater engineer[edit]

On January 1, 1659—after Angelini's death—Lodovico Ottavio Burnacini was appointed as imperial court architect and stage designer, a position he held for the rest of his life.[8] From the very beginning, Lodovico Ottavio had to prove himself with all the skills of his art, because in Vienna, plays, concerts and ballets were performed almost daily at the imperial court. Church holidays, carnival, state visits as well as joyful events at the court such as weddings, births, coronations etc. naturally gave rise to a demand for increasingly greater festivities. For such events the young theater engineer not only designed stage decorations and costumes, but had to build entire theaters and to invent stage machines and parade floats that served to amuse the emperor and his guests. Although it was interrupted by the plague in 1679 and the Turkish siege in 1683, there was an extremely lively cultural life in Vienna in the late 17th century, in which Burnacini played a major role.

The comedy house on the Rosstummelplatz[edit]

The wooden theater, which Giovanni Burnacini had built in Regensburg in 1653 on the occasion of the Reichstag, was dismantled and shipped down the Danube to Vienna, to be re-erected on the Rosstummelplatz (riding arena) in summer 1659, at Emperor Leopold I's request. It became an extremely popular comedy house and was an impressive theater “in the size and height of a fairly large church building” with a spacious ground floor and two tiers with 60 boxes (“Zimmerl”), which is said to have offered space for “several thousand people”. The multiple backdrops allowed scene changes “well eight manner without pulling a single curtain.”[9][10][11]

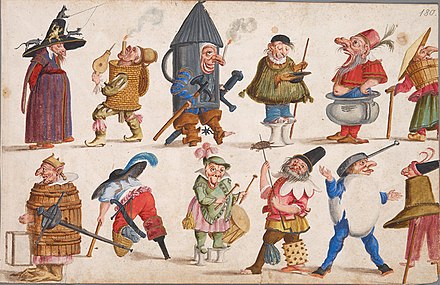

Although this comedy house was demolished in 1662, due to the opposition of the Jesuits[12] and perhaps also in connection with the death of Archduke Leopold Wilhelm, the uncle of Emperor Leopold I, it marked an important episode in the history of the Commedia dell'arte in Vienna. Well-known acting troops had been invited to perform there, playing "every day except Friday".[13] The most famous comedians in Europe made guest appearances in Vienna, such as the Arlecchino Domenico Biancolelli (1636–1688).[14] Possibly in homage to the comedies played between 1660 and 1662, Burnacini later drew many of his grotesques and Commedia dell'arte characters, which are now kept in the Theatermuseum in Vienna.

The theater auf der Kurtine – the new court theater[edit]

Between 1666 and 1668 Lodovico Ottavio Burnacini constructed the so-called Theater auf der Kurtine,[15] which rose next to the fortification of the imperial palace (Burgbastei) at the site of today’s court library, near Josefsplatz.

In this theater the most magnificent operas of the Leopoldin court were performed, first and foremost Antonio Cesti's Il pomo d’oro (1668) on occasion of the first wedding of Leopold I with the Spanish infanta Margarita Teresa and of her 17th birthday. For this opulent opera Burnacini created 23 different stage decorations that captivated the audience through rapid changing of scenes and through other stage machines of various kinds. Il pomo d'oro became known all over the world through the prints by Matthäus Küsel and Frans Geffels based on Burnacini's designs. This and other operas, whose libretti were magnificently complemented with large-format engravings, such as Il fuoco eterno delle Vestali (1674) composed by Antonio Draghi and the Monarchia latina trionfante (1678) composed by Draghi and Johann Heinrich Schmelzer vastly contributed to Burnacini's international reputation.

In 1688, after a visit to Vienna, the Swedish architect and art collector Nicodemus Tessin the younger wrote:

Bejim H. Burnacini der trusser undt ingegner vom Keijsser ist, habe ich alles höffligkeit genossen, in theatern undt festen wirdt heüt zu tage dass gröste lumiere von allen haben.[16] ("At Mr. Burnacini's, who is steward and engineer of the emperor, I enjoyed all courtesy; concerning theater and festivities nowadays he will be the most luminous one").

Tessin also described some features of the famous theater, which had to be dismantled shortly before the Turkish siege in 1683, because of the high risk of fire.

Burnacini as an architect[edit]

In 1676/1677 Burnacini was commissioned to rebuild Laxenburg Castle and after the Turkish siege in 1683 he directed the reconstruction of Ebersdorf Castle.

In the mid-1680s, he made designs for the Pestsäule (Trinity or Plague Column) on the Viennese Graben, which were carried out in 1687 under his direction by the brothers Peter and Paul Strudel, with whom, according to Tessin, he was friends.[16] Some sketches and drafts of this project have been preserved in the Theatermuseum in Vienna.[17]

In the last decades of the 17th century, “almost all public and private monuments were created according to his ideas and designs”.[18] Emperor Leopold I also entrusted him with the reconstruction of the destroyed Favorita, the building that would later become the Theresianium.

In 1698 Burnacini, together with Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach, started building the Mehlgrube ("flour pit") on the Neuer Markt.

Death[edit]

Lodovico Ottavio worked for the imperial court for over 55 years and remained in office until he died at an advanced age on December 12, 1707 from pneumonia in his house zur goldenen Säule ("at the golden column") on Vienna's Judenplatz.[19]

Honors and salary[edit]

Beginning on February 1, 1665 Lodovico Ottavio Burnacini received a modest annual salary of 600 fl. (Angelini had received 720 fl., like Giovanni Burnacini). In 1671 this salary was increased by 300 fl. and in 1678 by a further 180 fl. With these 1,080 fl. a year, he was then reconfirmed in his office after the death of Emperor Leopold I by his son and successor Joseph I.[7]

In 1677 he was awarded the title of Imperial Truchsess (Seneschal), in 1702 the baronial status and in 1706—a year before his death—the title of a Mundschenk (cup-bearer).

Family and marriages[edit]

Lodovico—Lodovico Ottavio's grandfather and progenitor of the Burnacini family—was an artillery man ("Bombardino") from Cesena, who married a certain 'Giustina'. Based on archival sources, it is known that he not only served in the military, but also in service of festivals, such as for the visit of the papal legate Cardinal Alessandro Orsini in 1621 in Cesena, where Giovanni prepared and set off wonderful illuminations and fireworks.[4] The artistic talent of the family can thus be traced back to this ancestor.

Grandfather Lodovico and Grandmother Giustina gave birth to five children: Francesco, Lodovico Ottavio's father Giovanni, Santa, Marcantonio and Nicola.

Giovanni married a certain 'Grazia' in 1630 and from their marriage—as far as can be gathered from the sources thus far available—had five children: Giustina, Lodovico Ottavio, Costanza, Giacomo and Antonio Felice. It seems likely that apart from Giovanni and Lodovico Ottavio, other members of the family were also gifted and involved in the activities of the workshop. This is suggested by statements made by Lodovico Ottavio in letters as well as descriptions found with various drawings.

Lodovico Ottavio married three times: (date?) Ursula Katharina Fenkhin († 1673), 1673 Maria Regina Langetlin († 1678) and 1680 Julia Sidonia Elisabeth von Dornwangen († 1732). No children resulted from these three marriages. According to his will, his last wife was his sole heiress. The only condition was that she should take under her care a niece of Lodovico Ottavio named Sofia, daughter of one of his brothers.

Graphic work[edit]

Printed works by or based on Burnacini's designs are scattered throughout libraries, museums and archives around the world. The approximately 410-sheet collection of original drawings from his artistic estate is preserved in the holdings of the Theatermuseum in Vienna. Thematically, this collection is divided into two large series. The first one, including numerous costume designs for festivities of the court (called Maschere by Burnacini, with inventory code Min 20); the second one (with inventory code Min 29) is far more heterogeneous and includes figurines for the Commedia dell'arte and grotesques, theater decorations, drafts for floats, festive sleighs as well as allegorical, mythological, sacral compositions and figures, architectural designs for various buildings and monuments, designs for centerpieces, candelabras and ceremonial vessels, nature studies, landscapes and genre scenes.

A recent publication by the Theatermuseum presents approximately 125 grotesque drawings by Burnacini in detail, which are related to the world of comedy.

Bibliography (chronological)[edit]

- Rudi Risatti (Hrsg.): Groteske Komödie in den Zeichnungen von Lodovico Ottavio Burnacini (1636–1707). Hollitzer, Vienna 2019, ISBN 978-3-99012-614-1.

- Andrea Sommer-Mathis – Daniela Franke – Rudi Risatti (Hrsg.): Spettacolo barocco! Triumph des Theaters, Imhof, Vienna (exhibition catalogue / Theatermuseum) 2016.

- Andrea Sommer-Mathis: Fest und Festung. Die Wiener Burgbefestigung als Bauplatz von Tanzsälen und Opernhäusern im 16. und 17. Jahrhundert, in: Österreichische Zeitschrift für Kunst und Denkmalpflege 64, 2010, pp. 83–92.

- Otto G. Schindler: Comici dell’Arte alle Corti Austriache degli Asburgo und Da Arlecchino a Kasperl. „Il Basilisco di Bernagasso“ nei paesi di lingua tedesca. In: Alberto Martino – Fausto de Michele (Hgg.): La ricezione della commedia dell’arte nell’Europa centrale 1568–1769. Storia, testi, iconografia. Pisa – Rome 2010, pp. 69–143 und 273–322.

- Samantha Santi o De Santi: Giovanni Burnacini (1610–1655) architetto e scenografo cesenate (doctoral thesis supervised by Elena Tamburini / University of Bologna, Institute for Art History), Bologna 2006/2007.

- Otto G. Schindler: Domenico Biancolelli e la rappresentazione del „Convitato di pietra“ a Vienna (1660). In: Commedia dell’arte. Annuario internazionale 1, 2008, pp. 161–180.

- Andrea Sommer-Mathis: Feste am Wiener Hof unter der Regierung von Kaiser Leopold I. und seiner ersten Frau Margarita Teresa (1666–1673). In: Fernando Checa Cremades (Hrsg.): Arte Barroco e ideal clasico. Aspectos del arte cortesano de la segunda mitad del siglo XVII, Madrid 2004, pp. 240–244.

- Andrea Sommer-Mathis: Lodovico Ottavio Burnacini, scenografo e costumista di Antonio Draghi. In: Emilio Sala – Davide Daolmi (Hrsg.), „Quel novo Cario, quel divin Orfeo“. Antonio Draghi da Rimini a Vienna. Atti del convegno internazionale (Rimini, Palazzo Buonadrata, 5–7 ottobre 1998) (ConNotazioni, Bd. 7), Lucca 2000, pp. 397–410.

- Otto G. Schindler: „Mio compadre Imperatore“. Comici dell’arte an den Höfen der Habsburger. In: Maske und Kothurn 38, Heft 2–4, 1997, pp. 25–154.

- Herbert Seifert: Der Sig-prangende Hochzeit-Gott. Hochzeitsfeste am Wiener Kaiserhof 1622–1699 (dramma per musica, Bd. 2), Wien 1988.

- Jean-Marie Valentin: „Il Pomo d’Oro“ et le mythe impérial Catholique à l’époque de Léopold Ier. In: XVIIe Siècle 36, 1984, pp. 17–36.

- Sabine Solf: Festdekoration und Groteske. Der Wiener Bühnenbildner Lodovico Ottavio Burnacini. Inszenierung barocker Kunstvorstellung (Studien zur deutschen Kunstgeschichte, Bd. 355), Baden-Baden 1975.

- Margaret Dietrich: Lodovico Ottavio Burnacini. In: Walter Pollak [Hrsg.]: Tausend Jahre Österreich. Eine biographische Chronik. Band 2. Wien / München: Jugend & Volk 1973, from p. 255.

- Flora Biach-Schiffmann: Giovanni und Ludovico Burnacini. Theater und Feste am Wiener Hofe (= Arbeiten des 1. Kunsthistorischen Instituts der Universität Wien [Lehrkanzel Strzygowski] Band 43). Krystall-Verlag, Vienna / Berlin 1931.

- Albert Ilg: Ein Porträt Burnacinis. In: Monatsblatt des Altertums-Vereines zu Wien 6 (1889), from p. 18, p. 32.

Selected designs[edit]

-

Stage set for the underworld in Antonio Cesti's opera Il pomo d'oro, 1668

-

Costume designs for grotesques and commedia dell'arte characters, 1680

-

Stage set for Antonio Draghi's opera La monarchia latina trionfante, 1678

Notes[edit]

- ^ Original documents indicate clearly, that the artist signed himself as "Lodovico Ottavio Burnacini". However, there is variant spellings of his surname, like Bernecini, Bornacini, Bornatini, Bournacini, and Bornazini, with his first name sometimes spelled as Ludovico and his second given name sometimes given as Ottaviano.

References[edit]

- ^ Brini, Amalia Barigozzi (1972)."Burnacini, Ludovico Ottaviano". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Vol. 15. Treccani. Retrieved online 3 July 2016 (in Italian).

- ^ Kábdebo, Heinrich (15 June 1879). "Zur Entwicklungs-Geschichte der Decorations- (Architektur-) Malerei in Wien". Österreichische Kunst-Cronik. Band II, Nr. 4: 62.

- ^ Ilg, Albert (1895). Die Fischer von Erlach. Vienna: Verlag von Carl Konegen. pp. 77, 79.

- ^ a b c Santi o De Santi, Samantha (2019). "Die Burnacini, eine Dynastie von Theateringenieuren. Neue Entdeckungen zu ihrer Herkunft". In Risatti, Rudi (ed.). Groteske Komödie in den Zeichnungen von Lodovico Ottavio Burnacini (1636-1707). Vienna: Hollitzer. pp. 39–61. ISBN 978-3-99012-614-1.

- ^ Risatti, Rudi, ed. (2019). Groteske Komödie in den Zeichnungen von Lodovico Ottavio Burnacini (1636-1707) (1. Auflage ed.). Vienna: Hollitzer. ISBN 978-3-99012-614-1. OCLC 1110686475.

- ^ Baumann, Wolfgang (1986). "Fastnacht und Fastenzeit 1653". In Möseneder, Karl (ed.). Feste in Regensburg. Von der Reformation bis in die Gegenwart. Regensburg. pp. 213–219.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Sommer-Mathis, Andrea (10 May 2019). "Eine kurze Biografie". In Risatti, Rudi (ed.). Groteske Komödie in den Zeichnungen von Lodovico Ottavio Burnacini (1636-1707). Vienna: Hollitzer. p. 16. ISBN 978-3-99012-614-1.

- ^ Sommer-Mathis, Andrea (2019). "Lodovico Ottavio Burnacini und die Commedia dell'arte am Wiener Hof". In Risatti, Rudi (ed.). Groteske Komödie in den Zeichnungen von Lodovico Ottavio Burnacini (1636–1707). Vienna: Hollitzer. pp. 63–80. ISBN 978-3-99012-614-1.

- ^ Theatrum Europæum. Vol. VII. Frankfurt am Main. 1663. p. 343.

- ^ Hadamowsky, Franz (1955). "Barocktheater am Wiener Kaiserhof. Mit einem Spielplan (1625–1740)". Jahrbuch der Gesellschaft für Wiener Theaterforschung. Annals 1951/1952. Vienna: 7–117.

- ^ Schindler, Otto G. (1997). ""Mio compadre Imperatore". Comici dell'arte an den Höfen der Habsburger". Maske und Kothurn. 38, Nr. 2–4: 25–154, here: 78.

- ^ Deisinger, Marko (2016). "Weltliches Vergnügen, die Jesuiten und ein spektakulärer Unfall im Theatersaal. Andrea D'Orsos Commedia dell'arte-Truppe am Wiener Kaiserhof 1660". Frühneuzeit-Info. Jg. 27. Vienna: 18–34.

- ^ Seifert, Herbert (1985). "Die Oper am Wiener Kaiserhof im 17. Jahrhundert". Wiener Veröffentlichungen zur Musikgeschichte. 25. Tutzing: 445, 650.

- ^ Schindler, Otto G. (2008). "Domenico Biancolelli e la rappresentazione del "Convitato di pietra" a Vienna (1660)". Commedia dell'arte. Annuario Internazionale 1: 161–180.

- ^ "Komödienhaus (Theater auf der Cortina)".

- ^ a b Laine, Merit; Magnusson, Börje (2002). Nicodemus Tessin the Younger. Sources – Works – Collections. Travel Notes 1673–77 and 1687–88. Stockholm. p. 411.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Bianconi, Lorenzo and Pestelli, Giorgio (2002). Opera on Stage, p. 311. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226045919

- ^ "Lodovico Ottavio Burnacini". Wien Geschichte Wiki. 8 June 2020.

- ^ Hajdecki, Alexander (1908). Quellen zur Geschichte der Stadt Wien. I. Abteilung: Regesten aus in- und ausländischen Archiven mit Ausnahme des Archives der Stadt Wien. Vol. Band VI., Reg. 6275–14352. Vienna. pp. 304, Reg. 11669.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

External links[edit]

![]() Media related to Ludovico Burnacini at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ludovico Burnacini at Wikimedia Commons