Mourasuchus

| Mourasuchus | |

|---|---|

| |

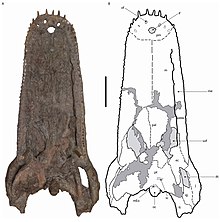

| Skull of Mourasuchus pattersoni | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Archosauromorpha |

| Clade: | Archosauriformes |

| Order: | Crocodilia |

| Family: | Alligatoridae |

| Subfamily: | Caimaninae |

| Genus: | †Mourasuchus Price 1964 |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Family-level:

Genus-level:

| |

Mourasuchus is an extinct genus of giant, aberrant caiman from the Miocene of South America. Its skull has been described as duck-like, being broad, flat, and very elongate, superficially resembling Stomatosuchus from the Late Cretaceous.[2][3]

History of discovery[edit]

Mourasuchus was first described by Price in 1964 based on a strange and nearly complete skull from the Solimões Formation of Amazonian Brazil, calling it Mourasuchus amazoniensis.[4] Unaware of Price's discovery, Langston described "Nettosuchus" atopus ("Absurd Duck Crocodile") only a year later based on fragmentary cranial, mandibular and postcranial remains from the middle Miocene La Venta Lagerstätte, a part of the Honda Group. Although he did recognize its similarities to caimans and alligators, Langston reasoned that its bizarre anatomy warranted its own monotypic family, naming it Nettosuchidae.[5] After being informed about the existence of Mourasuchus by Mr. W.D. Sills, Langston wrote a follow-up publication acknowledging his taxon to be a junior synonym of Mourasuchus.[6]

A third species was found in the Urumaco Formation of Venezuela in 1984 and named Mourasuchus arendsi by Bocquentin-Villanueva. Following this discovery, "Carandaisuchus" nativus was named in 1985 based on fossils of the Ituzaingó Formation of Argentina, as well as remains from Brazil and Bolivia.[7] However, by 1990 Caraindaisuchus had been lumped into Mourasuchus[8] and Scheyer & Delfino (2016) eventually concluded that M. nativus was merely a junior synonym of M. arendsi,[9] bringing the number of species from four to three. It wasn't long until the genus returned to four species however, with M. pattersoni (named after Anglo-American paleontologist Bryan Patterson) being described by Cidade et al. the following year.[10] Indeterminate Mourasuchus fossils were found in the Yecua Formation of Bolivia.[11]

Description[edit]

Mourasuchus is well known for its strange anatomy, its skull exceptionally dorsoventrally flattened, broad, and overall platyrostral in shape, differing greatly from any other caiman currently known, most closely resembling the enigmatic crocodyliform Stomatosuchus from the Late Cretaceous Bahariya Formation. The nares are elevated and so is the high postrostral cranium and short skull table. The orbital margins are likewise raised above the rostrum with thickened anteromedial margins formed by a knob-like swelling of the frontal and prefrontal bones. Overall, the orbits are smaller than the infratemporal fenestrae. The teeth were generally small and conical, numbering upwards of 40 teeth on each side of the upper and lower jaw and interlocking perfectly. The posterior teeth of the dentary and maxilla are laterally compressed. The premaxilla of Mourasuchus show noticeably large occlusal pits, especially noticeable in M. arendsi. However, such pits can be observed in a variety of extant and fossil taxa and are not considered to be diagnostic between species of Mourasuchus.

The mandible is U-shaped with a sharp transition between the first five teeth and the rest of the dentary teeth. The first to fifth tooth are located on the curved anterior portion of the mandible, while the bone is straight from the sixth onward. The mandibular symphysis is short and slender, only extending to the first posterior alveoli, meaning the animal most likely had a relatively weak bite. The osteoderms of Mourasuchus show conspicuous spines on their dorsal surface.[12]

The humerus of Mourasuchus is long and slender and interpreted to possibly indicate weakened forelimbs, potentially corresponding with a predominantly aquatic lifestyle.[13]

Size[edit]

Due to the fragmentary remains of Mourasuchus the body size is difficult to determine. Mourasuchus skulls range up to a meter (3.3 ft) in length, with the holotype skull of M. pattersoni being 108.1 centimetres (42.6 in) long while that of M. arendsi could reach a length of 108.5 centimetres (42.7 in) long. The largest skull belongs to M. amazonensis at 113.5 centimetres (44.7 in). In a 2020 study, Cidade et al. attempted to determine the body sizes of the four recognized Mourasuchus species based on the head: body ratio of modern genera like Caiman latirostris and Alligator mississippiensis. Their results recovered a mean body size of 6.3 m (21 ft) and 1.2 metric tons (1.3 short tons) for M. atopus, the smallest species, and upwards of 9.5 m (31 ft) and 4.4 metric tons (4.9 short tons) for M. amazonensis.[13] However, a later study contradicted these results. In 2022 Paiva and colleagues argued that the dorsal cranial length was a poor basis for size estimates compared to the width of the skull. Additionally, they found that prior studies commonly included juvenile animals in their data, muddying the results. This study calculated a length between 2.5–3.1 m (8 ft 2 in – 10 ft 2 in) for Mourasuchus atopus, 3.8–4.8 m (12–16 ft) for Mourasuchus arendsi, 4.3–5.5 m (14–18 ft) for Mourasuchus pattersoni and for Mourasuchus amazoniensis, the largest species, 4.7–5.98 m (15.4–19.6 ft). These results were achieved by specifically restricting the dataset to extant species of caimans, while calculations using measurements from all of Crocodilia generally rendered greater sizes but may be overestimates. Still, the authors note that the generally smaller stature of modern caimans may have influenced the results in a similar fashion.[14]

Phylogeny[edit]

Although Mourasuchus has been firmly placed within Caimaninae by authors, the exact relationship it has with other crocodilians of this family and even the relationship between the different species of the genus had long been unclear. Some studies have proposed that Mourasuchus was closely related to the Eocene Orthogenysuchus from North America, and more distantly to the giant caiman Purussaurus which it shared its habitat with. However, more recent papers indicate that ongoing preparation conducted on Orthogenysuchus significantly influences the scoring of this taxon's characters, leading to some authors removing the animal from analysis until further publications. The cladogram below shows the phylogenetic tree used by Bona et al. (2012).[15]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The following tree is based on the results recovered by Cidade et al. (2017), excluding the North American Orthogenysuchus and including the then newly named Mourasuchus pattersoni while also following the synonymy of M. nativus with M. arendsi. Like Bona et al. before them, the authors recover Mourasuchus and Purussaurus as closely related clades, this time as sister genera with Centenariosuchus just outside this shared clade.[10]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology[edit]

Diet[edit]

Much like with the unrelated but morphologically similar Stomatosuchidae, the feeding ecology of Mourasuchus is enigmatic and poorly understood, with a variety of hypotheses having been proposed to make sense of its specialized anatomy. With slender and short mandibular rami and perfectly occluding, slender and almost homodont teeth, Mourasuchus was not built to capture and hold prey like modern crocodilians.[8][5] In his 1965 publication on the crocodilians of Cenozoic Columbia, Langston proposed three ideas on how Mourasuchus may have fed. He suggests that it may have waited with opened jaws for approaching prey, fed on aquatic and floating plant material or searched for prey by sifting through substrate at the bottom of bodies of water.[5] While his other hypothesis have gone without much attention, the later of the three has been discussed by later publications, referring to this ecology as either "filter feeding", "straining technique" or "gulp feeding". Cidade et al. follow Langston's proposed feeding hypothesis, speculating that Mourasuchus may have fed on small invertebrates, mollusks, crustaceans, and small fish, specializing in trying to ingest as much prey at once as possible. This they suggest explains the platyrostral-broad skull morphology, which differs from the usual crocodilian skull morphology that typically either favors longirostrine forms providing speediness or robust-snouted forms with increased bite force.[8] Langston also proposed a throat pouch based on comments Franz Nopsca made regarding Stomatosuchus, however there is no evidence for such a structure in Mourasuchus nor is its presence certain in stomatosuchids. As the prey Mourasuchus would have fed on in accordance with the straining technique hypothesis would likely be found either in free water or substrate, the animal would have also captured inedible material during feeding. For this a type of filtering mechanism or behavior would be beneficial, however nothing indicating as much has been found so far. Due to the absence of evidence for actual filtering, Cidade et al. instead favors the term "gulp feeding" for Mourasuchus hypothetical hunting behavior.

In a 2020 study Cidade et al. aimed to determine Mourasuchus ability to perform the death roll, a crucial behavior observed in modern crocodiles and alligators that is commonly observed during feeding, when crocodiles rapidly spin to rip pieces of flesh from their prey. The study calculated a very low "death roll" capability indicator (DRCI) similar to that seen in the Slender Snouted Crocodile, Indian Gharial and False Gharial, which suggests that Mourasuchus was very unlikely to be able to perform the death roll.

Paleoenvironment[edit]

Mourasuchus lived during an era of great crocodilian diversity in South America, being found in environments shared with genera inhabiting a diverse set of niches. In the Peruvian Pebas Formation M. atopus was found alongside the large bodied Purussaurus neivensis, a medium-sized species of Gryposuchus, G. pachakamue and three distinct taxa of durophagous caimans. The later species M. arendsi coexisted with an even greater host of contemporary crocodilians in the Urumaco Formation, sharing its habitat with the larger Purussaurus mirandai, several large-bodied gharials, multiple durophagous caimans and the true crocodile Charactosuchus. In some areas such as the Urumaco and Solimões Formation multiple species of Mourasuchus are known, with the former being home to both M. pattersoni and M. arendsi while the later has yielded M. arendsi and M. amazonensis.[8] The great diversity of crocodylomorphs in these Miocene-age (Tortonian stage, 8 million years ago) wetlands suggests that niche partitioning was efficient, which would have limited interspecific competition.[16]

References[edit]

- ^ Rio, Jonathan P.; Mannion, Philip D. (6 September 2021). "Phylogenetic analysis of a new morphological dataset elucidates the evolutionary history of Crocodylia and resolves the long-standing gharial problem". PeerJ. 9: e12094. doi:10.7717/peerj.12094. PMC 8428266. PMID 34567843.

- ^ Brochu, C. A. (1999). "Phylogenetics, Taxonomy, and Historical Biogeography of Alligatoroidea". Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Memoir. 6: 9–100. doi:10.2307/3889340. JSTOR 3889340.

- ^ Villanueva, J. B.; Souza Filho, J. P. (1990). "O crocodiliano sul-americano Carandaisuchus como sinonímia de Mourasuchus (Nettosuchidae)". Revista Brasileira de Geociências. 20: 230–233. doi:10.25249/0375-7536.1990230233.

- ^ Price, L. I. (1964). "Sôbre o crânio de um grande crocodilídeo extinto do alto Rio Juruá, Estado do Acre". An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc. 36 (1): 59–66.

- ^ a b c Langston, W. (1965). Fossil crocodilians from Colombia and the Cenozoic history of the Crocodilia in South America. University of California Publications in Geological Sciences 52. University of California Press. pp. 1–152.

- ^ Langston, W. (1966). "Mourasuchus Price, Nettosuchus Langston, and the family Nettosuchidae (Reptilia: Crocodilia)". Copeia. 1966 (4): 882–885. doi:10.2307/1441424. JSTOR 1441424.

- ^ Gasparini, Z. B. (1985). "Un nuevo cocodrilo (Eusuchia) Cenozoico de América del Sur". Coletânea de Trabalhos Paleontológicos do IIX Congresso Brasileiro de Paleontologia, MME-DNPM. 27: 51–53.

- ^ a b c d Bocquentin, Jean-Claude; De Souza Filho, Jonas Pereira (1990). "O Crogodiliano Sul-Americano Carandaisuchus como sinonímia de Mourasuchus (Nettosuchidae)". Revista Brasileira de Geociências. 20: 230–233. doi:10.25249/0375-7536.1990230233.

- ^ Scheyer, T.M., and M. Delfino. 2016. The late Miocene caimanine fauna (Crocodylia: Alligatoroidea) of the Urumaco Formation, Venezuela. Palaeontologia Electronica 19. 1–57. Accessed 9 October 2018.

- ^ a b Cidade, G.M.; A. Solórzano; A.D. Rincón; D. Riff, and A.S. Hsiou. 2017. A new Mourasuchus (Alligatoroidea, Caimaninae) from the late Miocene of Venezuela, the phylogeny of Caimaninae and considerations on the feeding habits of Mourasuchus. PeerJ 5. 1–37. Accessed 9 October 2018. Archived 9 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Tineo, D.E.; P. Bona; L.M. Pérez; G.D. Vergani; G. González; D.G. Poiré; Z. Gasparini, and P. Legarreta. 2015. Palaeoenvironmental implications of the giant crocodylian Mourasuchus (Alligatoridae, Caimaninae) in the Yecua Formation (late Miocene) of Bolivia. Alcheringa 39. 1–12. Accessed 9 October 2018.

- ^ Langston (2008). "Notes on a partial skeleton of Mourasuchus (Crocodylia, Nettosuchidae) from the Upper Miocene of Venezuela". Arquivos do Museu Nacional, Rio de Janeiro. 66 (1): 125–143.

- ^ a b Cidade, Giovanne M.; Rincón, Ascanio D.; Solórzano, Andrés (2020). "New cranial and postcranial elements of Mourasuchus (Alligatoroidea: Caimaninae) from the late Miocene of Venezuela and their palaeobiological implications". Historical Biology. 33 (10): 2387–2399. doi:10.1080/08912963.2020.1795844. S2CID 225395230.

- ^ Paiva, Ana Laura S.; Godoy, Pedro L.; Souza, Ray B. B.; Klein, Wilfried; Hsiou, Annie S. (13 August 2022). "Body size estimation of Caimaninae specimens from the miocene of South America". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 118: 103970. Bibcode:2022JSAES.11803970P. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2022.103970. ISSN 0895-9811. S2CID 251560425.

- ^ Bona, Paula; Degrange, Frederico J.; Fernández, Marta S. (2012). "Skull Anatomy of the Bizarre Crocodylian Mourasuchus nativus (Alligatoridae, Caimaninae)". Anatomical Record. 296 (2): 227–239. doi:10.1002/ar.22625. hdl:11336/24984. PMID 23193096. S2CID 32793915.

- ^ Salas Gismondi, R.; P.O. Antoine; P. Baby; S. Brusset; M. Benammi; N. Espurt; D. de Franceschi; F. Pujos, and J. Tejada and M. Urbina. 2007. Middle Miocene crocodiles from the Fitzcarrald Arch, Amazonian Peru In: Díaz-Martínez, E. and Rábano, I. (eds.), 4th European Meeting on the Palaeontology and Stratigraphy of Latin America. Cuadernos del Museo Geominero, Instituto Geológico y Minero de España 8. . Accessed 9 October 2018.

- Alligatoridae

- Prehistoric pseudosuchian genera

- Miocene crocodylomorphs

- Miocene reptiles of South America

- Friasian

- Colloncuran

- Laventan

- Mayoan

- Chasicoan

- Huayquerian

- Neogene Argentina

- Neogene Bolivia

- Neogene Colombia

- Neogene Peru

- Neogene Venezuela

- Fossils of Argentina

- Ituzaingó Formation

- Fossils of Bolivia

- Fossils of Colombia

- Honda Group, Colombia

- Fossils of Peru

- Fossils of Venezuela

- Fossil taxa described in 1964