Persecution of Greeks in the Ottoman Empire 1914–1923

In the years 1914 to 1923 there was a wave of persecution of the Greeks in the Ottoman Empire , which resulted in the so-called Asian Minor catastrophe (Greek Μικρασιατική Καταστροφή) - i.e. the expulsion of the Greeks from the west coast of Asia Minor and the escape-like dissolution of the there in the course of the Greek-Turkish War (1919–1922) established state institutions - and culminated in violent measures against the Greeks of Eastern Anatolia .

During the First World War and the following years, the government of the Ottoman Empire ordered the killing of numerous Greek residents of the peninsula of Asia Minor . The measures included massacres , deportations and death marches , and finally the expulsion and resettlement of the survivors. According to various widely divergent sources, several hundred thousand Ottoman Greeks died during this time. Some of the survivors and refugees, especially those in the eastern provinces ( Vilayets ), fled to the neighboring Russian Empire . After the end of the Greco-Turkish War, a forced population exchange took place: most of the surviving Greeks had to leave the Ottoman Empire in 1923 and moved from Lausanne to Greece under the terms of the Treaty . In return, most of the Turks in Greece were relocated to Turkey .

The government of the Republic of Turkey - legal successor to the Ottoman Empire - claims to this day that the persecutions and expulsions were triggered by the assumption of the government at the time that the Greek population in Turkey supported the war opponents of the Ottoman state. The allies of the First World War and numerous foreign observers of the events saw it differently and condemned the massacres as crimes against humanity .

Historical background and causes

Greeks had lived on the west coast of Asia Minor since the middle of the second millennium BC, at the time of Homer . Since the seventh century BC The colonies were founded on the coast of the Black Sea , later the Pontus region , and the Cappadocian hinterland was partially settled . In Byzantine times , the Greek influence on the entire peninsula of Asia Minor was strengthened by administrative measures; Asia Minor was the heartland of the Greek-speaking empire for a long time. At the outbreak of the First World War, the population of Anatolia was ethnically diverse; lived there Turks , Greeks, Armenians , Kurds , Zaza , Circassian , Syrians ( Assyrians ), Turkish Jews , Laz and Azerbaijanis .

Among the reasons for the Ottoman campaign against the Greek population is the fear of the Ottoman government that the Ottoman-Greek population would help the opponents of the Ottoman Empire. When Eleftherios Venizelos came to power , Greece had become closely allied with the Triple Entente and was now clearly part of the opposing camp of the Central Powers with which the Ottoman Empire was allied. In addition, some responsible persons expressed the conviction that the Ottoman Empire had to be "cleansed" of the various national groups that could endanger the integrity of a Turkish state nation. Then one could found an "ethnically pure" Turkish nation-state. According to the German military attaché, the Ottoman War Minister Ismail Enver declared in October 1915 that he intended "to solve the Greek problem during the war [...] in the same way that he [e] believes to solve the Armenian problem."

Events

| Province (Vilâyet) | Turks | Greeks | Armenians | Jews | Other | total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Istanbul Asian shore |

135,681 | 70.906 | 30,465 | 5,120 | 16,812 | 258.984 |

| İzmit | 184,960 | 78,564 | 50,935 | 2,180 | 1,435 | 318.074 |

| Aydın ( Smyrna ) | 974.225 | 629.002 | 17,247 | 24,361 | 58,076 | 1,702,911 |

| Bursa | 1,346,387 | 574,530 | 87,932 | 2,788 | 6.125 | 1,717,762 |

| Konya | 1,143,335 | 85,320 | 9,426 | 720 | 15,356 | 1,254,157 |

| Ankara | 991.666 | 54,280 | 101,388 | 901 | 12,329 | 1,160,564 |

| Trabzon | 1,047,889 | 351.104 | 45.094 | - | - | 1,444,087 |

| Sivas | 933,572 | 98,270 | 165.741 | - | - | 1,197,583 |

| Kastamon | 1,086,420 | 18,160 | 3,061 | - | 1,980 | 1,109,621 |

| Adana | 212.454 | 88.010 | 81,250 | - | 107,240 | 488,954 |

| Bigha | 136,000 | 29,000 | 2,000 | 3,300 | 98 | 170,398 |

| All in all | 8,192,589 | 1,777,146 | 594,539 | 39,370 | 219.451 | 10,823,095 |

| Population share | 75.7% | 16.42% | 5.50% | 0.36% | 2.03% | |

| Total in 1912 | 7,048,662 | 1,788,582 | 608.707 | 37,523 | 218.102 | 9,695,506 |

| Population share | 72.7% | 18.45% | 6.28% | 0.39% | 2.25% |

As early as the summer of 1914, the secret guerrilla organization Teşkilât-ı Mahsusa , supported by officials from the government and the army, forced Greek men of military age from Thrace and Western Anatolia into labor battalions in which hundreds of thousands died. Sent hundreds of miles into the interior of Anatolia, these conscripts were put to work in road and tunnel construction, construction and field work, the number of which was greatly reduced - either through deprivation and mistreatment or through outright killings and massacres by the Turkish guards. This program of compulsory recruitment was later extended to other regions of the empire, including the Pontus .

The forced labor of Greek men was accompanied by deportations of the general population, some of which took on the character of death marches. In addition, Greek villages and cities were deliberately trapped by Turks and their residents massacred. One such event was reported on June 12, 1914 from the western Anatolian city of Phokaia ( Greek Φώκαια ), twenty-five miles northwest of Smyrna ; the disfigured corpses of men, women and children were then thrown into wells.

In July 1915, the Greek Chargé d'Affaires Tsamados declared that the deportations “could not be anything other than a war of extermination against the Greek nationality in Turkey; Measures taken in this regard were forced conversions to Islam, so that if there were to be another European intervention to protect Christians after the war, as few as possible would remain. "According to George W. Rendel of the British Foreign Office," over 500,000 Greeks deported, of whom comparatively few survived. "In his memoirs, the Ambassador of the United States between 1913 and 1916, Henry Morgenthau, wrote :" Everywhere the Pontic Greeks are put together in groups and are, under the so-called protection of the Turkish gendarmerie , inside the country transported - most of it on foot . How many were isolated and scattered along this route is not clearly known, the estimates range from 200,000 to 1,000,000. "

On January 14, 1917, the Swedish ambassador to Constantinople Cosswa Anckarsvärd sent a dispatch on the deportations of the Ottoman Greeks:

“What appears to be harsh cruelty in the first place is that the deportations are not limited to men alone, but are also extended to women and children alike. This is presumably done in order to have the possibility of confiscating the property of the deportees far more easily. "

Methods of extermination that indirectly caused death - such as deportations including death marches, starvation in labor camps, and the concentration camps - were referred to as "white massacres". The Turkish courts-martial of 1919 and 1920 provided indictments against a number of leading Turkish officials for their roles in the massacres against Greeks and Armenians. In a report from October 1920, the British officer describes a massacre in İznik , northwestern Anatolia , by reporting that at least 100 mutilated bodies of men, women and children were brought into and around a cave outside the city walls.

The already systematic massacre of the Greeks from Asia Minor and the accompanying deportations since 1914 was followed by the Greco-Turkish War with the occupation of the predominantly Greek-inhabited Smyrna in May 1919 on the basis of a League of Nations mandate . In this war both sides committed a mutual massacre this time. Between May 1919 and September 1922, the Greek troops also carried out attacks against Turkish cities and villages in the part of western Anatolia they had occupied. In Alaşehir , ancient Philadelphia, 4,300 of 4,500 houses were destroyed and 3,000 people were killed. In Manisa , the ancient magnesia, only 1,400 of 14,000 houses remained intact. The Greek occupation ended in September 1922, after which the Greek population began to flee in panic. On September 13, 1922, a fire broke out in the Armenian quarter of the city, which quickly spread to the quarters of the Greeks and western foreigners (the so-called "Franks") and destroyed a large part of Smyrna; in Greek historiography this event is referred to as the catastrophe of Smyrna (Καταστροφή της Σμύρνης). This event became the emblematic image of the catastrophe in Asia Minor in the Greek memoria .

The historian Arnold J. Toynbee took the view that it was the Greek occupation that led to the founding of the Turkish national movement by Mustafa Kemal and thus to an aggravation of the nationality question: “The Greeks of Pontus and the Turks in the Greek-occupied territories to a certain extent victim of the original miscalculation by Messrs Venizelos and Lloyd George in Paris. ”Toynbee thus placed the massacres in the context of Greece's irredentist policy, according to which predominantly Greek-populated areas were to be freed from foreign rule ( Megali Idea ).

Relief operations

In 1917, a charity named was in response to the ongoing deportations and massacres Relief Committee for the Greeks of Asia Minor (English Relief Committee for Greeks of Asia Minor ) was founded. The committee worked in cooperation with the American Near East Relief to distribute aid to the Ottoman Greeks in Thrace and Asia Minor. The organization was dissolved in the summer of 1921, but the Greek relief work was continued by other organizations.

Contemporary reactions

The reports of German and Austro-Hungarian diplomats as well as the memorandum compiled by George William Rendel in 1922 on “Turkish massacres and expulsions” provide important evidence for a series of systematic massacres of Greeks in Asia Minor. The quotations go back to various ambassadors and consuls of the Central Powers at the Sublime Porte, above all to the German ambassadors Hans Freiherr von Wangenheim and Richard von Kühlmann , the German vice-consul in Samsun Kuchhoff, the Austrian ambassador János von Pallavicini and the Austrian consul in Samsun Ernst von Kwiatkowski and the unofficial agent in Ankara , the Italian Tuozzi; the German Empire and Austria-Hungary were allies of the Ottoman Empire in the First World War. Various clergy and political activists also reported on the events, above all the German missionary Johannes Lepsius and Stanley Hopkins from the American Committee for Relief in the Near East . The reports name systematic massacres, rapes and burnings of Greek villages and describe the related intentions of Turkish officials, namely Turkish Prime Ministers Mahmud Şevket Pascha , Rafet Bey, Talat Pascha and Enver Pascha .

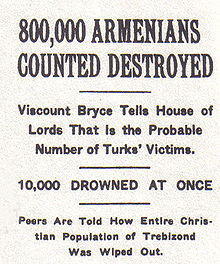

In addition, the New York Times correspondents reported extensively on massacres, deportations, individual murders, rape, burning of entire Greek villages, destruction of Greek Orthodox churches , plans to form labor battalions , looting, terrorism and other atrocities against Greek, Armenian citizens, but also to British and American citizens and government officials. The newspaper received its first Pulitzer Prize in 1918 "for the most disinterested and deserving public service rendered by an American newspaper - full and accurate coverage of the war." Other media covered the events of the time under similar titles.

Henry Morgenthau , the United States Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire from 1913 to 1916, accused the “Turkish government” of campaigning “hideous terrorization, cruel torture, driving women into harems , raping innocent girls, selling many of them for each 80 cents, the deportation and murder of hundreds of thousands and the starvation of hundreds of thousands after the expulsion into the desert, as well as the destruction of thousands of villages and many cities - all part of a deliberate execution of a scheme for the extermination of the Armenian, Greek and Syrian Christians of Turkey. "

US Consul General George Horton reported that "one of the cleverest statements circulated by Turkish propagandists is the claim that the Christians who were massacred were as bad as the murderers, that it was 50-50." : “ If the Greeks had massacred all the Turks in Greece after the massacres in Pontus and Smyrna, the record would have been close to 50-50. ”Like an eyewitness, he also praised the Greeks for their“ behavior […] towards the thousands of Turks in Greece while the cruel massacres continued […], [which in his opinion] was one of the most stimulating and beautiful chapters in the history of all countries . "

Victim

Various sources put the death toll in the genocide of the Pontic Greeks in Anatolia between 300,000 and 360,000. The estimates for the death toll of Greeks from Asia Minor as a whole are significantly higher.

According to reports by the International League for the Rights and Freedom of Peoples' Rights between 1916 and 1923, up to 350,000 Greek Pontic Greeks were killed in massacres, evictions and death marches. History professor Merrill D. Peterson confirms that the death toll among the Pontic Greeks is 360,000. According to George K. Valavanis, “the destruction of human life among the Pontic Greeks since the Great War [sci. the First World War] by March 1924, 353,000 people were killed as a result of murders, hangings, punishments, illnesses and other hardships. ”The Greek journalist and historian Tassos Kostopoulos has shown that this figure is the result of the arbitrary addition of 50,000 dead to 303,238, which was presented in a Greek brochure from 1922 to sensitize the common opinion about the persecution of the Greeks of Asia Minor by The pamphlet spoke of 303,238 displaced people, but Valavanis incorrectly portrayed them as exterminated. The number of c. 350,000 dead, founded by Valavanis as early as 1925, were reproduced by numerous Pontic Greek activists and have attained the official status mentioned in almost all memorial ceremonies. Kostopoulos estimates the number of Pontus Greeks exterminated between 1912 and 1924 at around 100,000 to 150,000 deaths.

Constantine Hatzidimitriou writes that "the loss of life among Anatolian Greeks during the period of World War I and its aftermath was approximately 715,370." According to Edward Hale Bierstadt, it states that "according to official testimony, the Turks have been cold blooded 1,500,000 Armenians since 1914 and Slaughtered 500,000 Greeks - men, women and children - for no reason whatsoever. ”At the Lausanne Conference in late 1922, British Foreign Secretary Lord Curzon was recorded as saying that“ a million Greeks were deported, killed or died ”.

aftermath

Article 142 of the Treaty of Sèvres of 1920, which was negotiated following the First World War, described the Turkish regime as “terrorist” and contained provisions that should serve “that in the course of the massacres of the war against individuals in Turkey wronged as much as possible. ”The Treaty of Sèvres was never ratified by the Turkish government and was ultimately replaced by the Treaty of Lausanne . This treaty was accompanied by a general amnesty and without any provision regarding the punishment of war crimes.

In 1923, the population exchange between Greece and Turkey led to an almost complete elimination of the ethnic Greek presence in Turkey and an analogous elimination of the ethnic Turkish presence in large parts of Greece. According to the 1928 Greek census, 1,104,216 Ottoman Greeks had reached Greece by that time. While the population of Greece was 5,050,000 in 1921, it had risen to 6,010,000 due to the refugees from Asia Minor.

Excluded from the population exchange were a total of 110,000 Greeks in Turkey and 106,000 Turks in Greece . The remaining Greeks later left Turkey as a result of the Istanbul pogrom of 1955, the number of Greeks in Turkey is estimated between 2,000 and 2,500 people today. The number of Western Thrace Turks in Greece currently amounts to 80,000 to 120,000 people.

To date, it is impossible to know exactly how many Greek residents of Turkey died between 1914 and 1923 and how many ethnic Greeks from Anatolia were expelled to Greece or the former Soviet Union . Some of the survivors and displaced persons found refuge in the neighboring Democratic Republic of Georgia (later Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic ; in present-day Georgia , many of their descendants are classified as Urumians ).

Legal and historical processing

Pre-academic terminology and recognition of the massacres

Before the scientific development of the term “genocide”, the extermination of the Ottoman Greeks was known to the Greeks themselves as “the massacre” (Greek η Σφαγή), as a “great catastrophe” (Μεγάλη Καταστροφή) or “great tragedy” (Μεγάλη Τρα .γωδία) Contemporary reports used terms such as annihilation, annihilation, extermination, "ongoing campaign of massacre", "major massacre" and systematic annihilation.

Academic research

According to historian Mark Mazower , the deportations of Greeks by the Ottomans “remained on a relatively small scale and do not appear to have been meant to end in the death of their victims. What would happen to the Armenians was of a different order of magnitude. ”In contrast, Niall Ferguson considers the use of the term“ genocide ”to be appropriate for the persecution of the Greeks - as for the fate of the Armenians. In addition, genocide researchers such as Dominik J. Schaller and Jürgen Zimmerer have found that the genocidal quality of the “murderous” campaign against the Greeks of Asia Minor is evident. In his book With Intent to Destroy: Reflections on Genocide , Colin Tatz argues that Turkey only denies genocide so as not to jeopardize the “ninety-five year old dream of becoming the beacon of democracy in the Middle East”. Elizabeth Burns Coleman and Kevin White present a list of reasons that explain Turkey's inability to recognize what they believe to be the genocide committed by the Young Turks .

Political Consequences

The Greek Parliament passed two laws on the fate of the Ottoman Greeks, the first in 1994 and the second in 1998. The decrees were published and reaffirmed in the Official Gazette of the Hellenic Republic on March 8, 1994 and October 13, 1998, respectively. The 1994 decree upheld the genocide in the Pontus region of Asia Minor and set May 19 as the Day of Remembrance . The Republic of Cyprus has also officially recognized the events as genocide.

In response to the 1998 law, the Turkish government issued a statement claiming that the description of the events as genocide "has no historical basis." The Turkish Foreign Minister said: “We condemn and protest against this resolution. With this resolution the Greek parliament, which in reality has to apologize to the Turkish people for the large-scale destruction that has taken place in Asia Minor , not only supports the traditional Greek policy of distorted history, but also shows the expansionist Greek spirit. " The law passed by the Greek government was also supported by domestic opposition. However, the Greek historian Angelos Elefantis said that the Greek parliament acted “like an idiot” in this matter, even though it subsumed the Smyrneean episode of the Asia Minor catastrophe under the term genocide, while the difficult situation of the Greek refugees was more the result of one failed military strategy of the Greek army command.

On March 11, 2010, a motion passed in the Swedish parliament , which recognized the events "as an act of genocide to kill all Armenians, Assyrians, Arameans, Chaldeans and Pontic Greeks in 1915".

Memorials

Memorials commemorating the plight of the Ottoman Greeks have been erected across Greece and a number of other countries including Germany, Canada, the United States, Sweden, Cyprus and most recently Australia.

See also

- Megali Idea

- Republic of Pontus

- Genocide against the Armenians

- Genocide of the Assyrians and Aramaeans

literature

Historical overview

- Neal Ascherson: Black Sea. 1st American edition. Hill and Wang, New York NY 1995, ISBN 0-8090-3043-8 .

- Charles King: The Black Sea. A history. Oxford University Press, Oxford u. a. 2005, ISBN 0-19-928394-X .

- William C. King (Ed.): King's Complete History of the World War. Visualizing the Great Conflict in all Theaters of Action 1914-1918. The History Associates, Springfield MA 1922, digitized .

- Marianna Koromila: The Greeks and the Black Sea. From the Bronze Age to the Early Twentieth Century. Panorama Cultural Society, Athens 2002, ISBN 960-87177-0-1 .

- Stanford J. Shaw , Ezel Kural Shaw: Reform, Revolution, and Republic. The Rise of Modern Turkey, 1808-1975 (= History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. Vol. 2). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge u. a. 1977, ISBN 0-521-21449-1 .

- Γεωργίου Κ. Βαλαβάνη: Σύγχρονος Γενική Ιστορία του Πόντου. Αφοί Κυριακίδη, Αθήναι 1925, (Modern, general history of Pontus).

Contemporary and recent sources and documents

- Edward Hale Bierstadt: The Great Betrayal. A Survey of the Near East Problem. McBride, New York NY 1924.

- Carl Hulse: US and Turkey Thwart Armenian Genocide Bill . In: The New York Times , October 26, 2007.

- Henry Morgenthau : Ambassador Morgenthau's Story. Doubleday, Page & Company Garden, New York NY 1918, online (PDF; 2.6 MB) .

- Henry Morgenthau: The Murder of a Nation. Armenian General Benevolent Union of America, New York 1918, (again: ibid. 1974).

- Henry Morgenthau: I Was Sent to Athens. In Collaboration with French Strother. Doubleday, Doran & Co, Garden City NY 1929, online .

- Henry Morgenthau: An International Drama. In Collaboration with French Strother. Jarrolds Ltd., London 1930.

- Jean De Murat: The Great Extirpation of Hellenism and Christianity in Asia Minor. The historic and systematic deception of world opinion concerning the hideous Christianity's uprooting of 1922. Triantafillis, Athen sa (again: Selbstverlag, Miami FL 1999, ISBN 0-9600356-7-2 ).

- Lysimachos Oeconomos: The Martyrdom of Smyrna and Eastern Christendom. A file of overwhelming evidence, denouncing the misdeeds of the Turks in Asia Minor and showing their responsibility for the horrors of Smyrna. G. Allen & Unwin, London 1922.

- Alexander Papadopoulos: Persecutions of the Greeks in Turkey before the European War. On the basis of official documents. Oxford University Press, New York NY 1919, digitized .

- Staff: Massacre of Greeks Charged to the Turks. In: The Atlanta Constitution , June 17, 1914.

- Mark H. Ward: The Deportations in Asia Minor, 1921-1922. Anglo-Hellenic League , London 1922.

Literature on the genocides in the Ottoman Empire (1914–1922)

Monographs

- Taner Akçam : From Empire to Republic. Turkish Nationalism and the Armenian Genocide. Zed Books, London a. a. 2004, ISBN 1-84277-527-8 .

- Taner Akçam: A Shameful Act. The Armenian Genocide and the Question of Turkish Responsibility. Metropolitan Books, New York NY 2006, ISBN 0-8050-7932-7 .

- George Andreadis: Tamama. The Missing Girl of Pontos. Gordios, Athens 1993.

- Vahagn Avedian: The Armenian Genocide 1915. From a Neutral Small State's Perspective: Sweden. Uppsala 2009, online (PDF; 1.0 MB) , (Uppsala, University, unpublished Master Thesis, 2009).

- James L. Barton: The Near East Relief, 1915-1930 (= Administration of Relief Abroad. 2). Russell Sage Foundation, New York NY 1943.

- James L. Barton: "Turkish Atrocities". Statements of American Missionaries on the Destruction of Christian Communities in Ottoman Turkey, 1915–1917 Gomidas Institute, Ann Arbor MI 1998, ISBN 1-884630-04-9 .

- M. Cherif Bassiouni : Crimes Against Humanity in International Criminal Law. 2nd, revised edition. Kluwer, The Hague et al. a. 1999, ISBN 90-411-1222-7 .

- Donald Bloxham: The Great Game of Genocide. Imperialism, Nationalism, and the Destruction of the Ottoman Armenians. Oxford University Press, Oxford u. a. 2005, ISBN 0-19-927356-1 .

- Carl C. Compton: The Morning Cometh. 45 years with Anatolia College. Aristide D. Caratzas, New Rochelle NY 1986, ISBN 0-89241-422-7 .

- Niall Ferguson : The War of the World. Twentieth Century Conflict and the Descent of the West. Penguin Group, New York NY 2006, ISBN 1-59420-100-5 .

- Constantinos Emm. Fotiadis: The Genocide of the Pontus Greeks by the Turks. = Η γενοκτονία των Ελλήνων του Πόντου. Volume 13: Archive Documents of the Ministries of Foreign Affairs of Britain, France, the League of Nations and SHAT = Αρχεία Υπουργείων Εξωτερικών Μ. Βρετανίας, Γαλλίας, Κοινωνίας των Εθνών και SHAT Herodotus, Thessaloniki 2004, ISBN 960-8256-19-4 .

- Thea Halo: Not Even My Name. A true story. From a Death March in Turkey to a new Home in America. A young Girl's true Story of Genocide and Survival. 1st Picador USA paperback edition. Picador, New York NY 2001, ISBN 0-312-27701-6 .

- Mirko Heinemann: The last Byzantines. The expulsion of the Greeks from the Black Sea. A search for clues . Ch. Links Verlag, Berlin 2019, ISBN 978-3-96289-033-9 .

- Tessa Hofmann (Ed.): Persecution, expulsion and extermination of Christians in the Ottoman Empire. 1912–1922 (= Studies on Oriental Church History. Vol. 32). Lit-Verlag, Münster 2004, ISBN 3-8258-7823-6 .

- George Horton: The Blight of Asia. An Account of the Systematic Extermination of Christian Populations by Mohammedans and of the Culpability of certain great Powers. With a true story of the Burning of Smyrna. Bobbs-Merrill Co., Indianapolis IN 1926, online .

- Marjorie Housepian Dobkin: Smyrna 1922. The Destruction of a City. Newmark Press, New York NY 1998, ISBN 0-9667451-0-8 .

- Isabel V. Hull : Absolute Destruction. Military Culture and the Practices of War in Imperial Germany. Cornell University Press, Ithaca NY et al. a. 2005, ISBN 0-8014-4258-3 .

- Ιωάννου Χαραλ. Καραγιαννίδη: Ο γολγοθάς του Πόντου. Το ξερίζωμα, τα πάθη και τα εγκλήματα εις βάρος του Ποντιακού Ελληνισμού. Ορφανίδης, Θεσσαλονίκη 1978, (The Golgotha of Pontus).

- Benjamin Lieberman: Terrible Fate. Ethnic Cleansing in the Making of Modern Europe. Ivan R. Dee, Chicago IL 2006, ISBN 1-56663-646-9 (again: Rowman & Littlefield et al., Lanham MD 2013, ISBN 978-1-4422-2319-6 ).

- Manus I. Midlarsky: The Killing Trap. Genocide in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge u. a. 2005, ISBN 0-521-89469-7 .

- Norman M. Naimark: Fires of Hatred. Ethnic Cleansing in Twentieth-Century Europe. Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA a. a. 2001, ISBN 0-674-00313-6 .

- Merrill D. Peterson: "Starving Armenians". America and the Armenian Genocide, 1915-1930 and After. University of Virginia Press, Charlottesville VA u. a. 2004, ISBN 0-8139-2267-4 .

- Heather Rae: State identities and the homogenization of peoples (= Cambridge Studies in International Relations. Vol. 84). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge u. a. 2002, ISBN 0-521-79708-X .

- Colin Tatz: With Intent to Destroy. Reflections on Genocide . Verso, London a. a. 2003, ISBN 1-85984-550-9 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- Samuel Totten, Steven Leonard Jacobs (Eds.): Pioneers of Genocide Studies . Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick NJ et al. a. 2002, ISBN 0-7658-0151-5 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- Harry Tsirkinidis: At last we uprooted them… The Genocide of Greeks of Pontos, Thrace and Asia Minor through the French archives. Kyriakidis Brothers sa, Thessaloniki 1999, ISBN 960-343-478-7 .

items

- Matthias Bjørnlund: The 1914 cleansing of Aegean Greeks as a case of violent Turkification. In: Journal of Genocide Research. Vol. 10, Issue 1, March 2008, pp. 41-58, doi: 10.1080 / 14623520701850286 .

- Nikolaos Hlamides: The Greek Relief Committee: America's Response to the Greek Genocide (A Research Note). In: Genocide Studies and Prevention. Vol. 3, Issue 3, December 2008, pp. 375-383, doi: 10.3138 / gsp.3.3.375 .

- Mark Levene: Creating a Modern "Zone of Genocide": The Impact of Nation and State Formation on Eastern Anatolia, 1878-1923. In: Holocaust and Genocide Studies. Vol. 12, No. 3, Winter 1998, pp. 393-433, doi: 10.1093 / hgs / 12.3.393

- Rudolph J. Rummel: Statistics of Turkey's democide. Estimates, calculations, and sources. In: Statistics of Democide. Retrieved May 30, 2015 .

- Hannibal Travis: The Cultural and Intellectual Property Interests of the Indigenous Peoples of Turkey and Iraq . In: Texas Wesleyan Law Review . tape 15 , 2009, p. 601-680 (English, ssrn.com ).

- Speros Vryonis, Jr .: Greek Labor Battalions in Asia Minor. In: Richard Hovannisian (Ed.): The Armenian Genocide. Cultural and Ethical Legacies. Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick NJ 2007, ISBN 978-0-7658-0367-2 , pp. 275-290.

Internet resources

Individual evidence

- ^ Adam Jones: Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction . Routledge, New York 2006, pp. 154-155.

- ↑ Norman M. Naimark: Fires of Hatred. Ethnic Cleansing in Twentieth-Century Europe . Harvard University Press, Cambridge and London 2001, p. 55.

- ^ EJ Hobsbawm: Nations and nationalism since 1780 program, myth, reality . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1992, ISBN 0-521-43961-2 , pp. 133 .

- ↑ Donald Bloxham: The Great Game of Genocide. Imperialism, Nationalism, and the Destruction of the Ottoman Armenians . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2005, p. 150.

- ^ Niall Ferguson: The War of the World. Twentieth Century Conflict and the Descent of the West . Penguin Press, New York 2006, p. 180.

- ↑ Dimitri Pentzopoulos: The Balkan exchange of minorities and its impact on Greece . C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2002, ISBN 978-1-85065-702-6 , pp. 29–30 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Statistics Ecumenical Patriarchate, 1912. Note: The smaller population in 1912 is also due to the loss of areas.

- ↑ Isabel V. Hull : Absolute Destruction. Military Culture and the Practices of War in Imperial Germany. Cornell University Press, Ithaca / NY 2005, p. 273.

- ^ William C. King: King's Complete History of the World War. Visualizing the Great Conflict in all Theaters of Action 1914-1918 ( Memento from August 1, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ) , The History Associates, Massachusetts 1922, p. 437.

- ↑ Staff: Massacre of Greeks Charged to the Turks . In: The Atlanta Constitution , June 17, 1914, p. 1.

- ↑ Vahagn Avedian: The Armenian Genocide of 1915 from a neutral Small State's Perspective: Sweden. In: Genocide Studies and Prevention , Volume 5, No. 3 (2010), pp. 323-340, doi: 10.3138 / gsp.5.3.323 , on p. 328.

- ↑ a b c d e G. W. Rendel: Foreign Office Memorandum on Turkish Massacres and Persecutions of Minorities since the Armistice , March 20, 1922.

- ^ Henry Morgenthau: Ambassador Morgenthau's Story , Doubleday, Page & Company, Garden City, New York, 1919.

- ↑ Vahagn Avedian: The Armenian Genocide in 1915. From a neutral Small State's Perspective: Sweden . Unpublished Master Thesis, Uppsala University, 2009, p. 47.

- ↑ Taner Akçam : Armenia and the Genocide: The Istanbul Trials and the Turkish National Movement . Hamburger ed. Hamburg 1996, p. 185 .

- ^ Arnold J. Toynbee: The Western question in Greece and Turkey. A study in the contact of civilizations . Houghton Mifflin, Boston 1922, p. 270.

- ^ RJ Rummel: Statistics of Turkey's democide. Estimates, calculations, and sources. In: Statistics of Democide. Retrieved October 4, 2006 .

- ↑ Andrew Mango , Ataturk. London 1999, ISBN 0-7195-5612-0 , p. 343.

- ^ Arnold J. Toynbee: The Western question in Greece and Turkey: a study in the contact of civilizations . Houghton Mifflin, Boston 1922, p. 312 f.

- ↑ Nikolaos Hlamides: The Greek Relief Committee: America's Response to the Greek Genocide . In: Genocide Studies and Prevention 3, December 3, 2008, pp. 375-383.

- ^ A b Australian Institute for Holocaust and Genocide Studies: the genocide and its aftermath ( Memento of March 17, 2003 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b Halo pp. 26, 27, & 28.

- ^ The New York Times Advanced search engine for articles and headline archives (subscription necessary for viewing article content).

- ↑ Alexander Westwood and Darren O'Brien, Selected bylines and letters from The New York Times ( Memento June 7, 2007, Internet Archive ), The Australian Institute for Holocaust and Genocide Studies , 2006, Retrieved October 14, 2008

- ^ Our Company, Awards ( August 20, 2008 memento on the Internet Archive ), The New York Times .

- ^ Vahe Georges Kateb (2003): Australian Press Coverage of the Armenian Genocide 1915-1923 ( Memento of July 10, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) , University of Wollongong, Graduate School of Journalism.

- ^ Morgenthau Calls for Check on Turks , New York Times, September 5, 1922, p. 3.

- ↑ a b Horton, September 2010

- ↑ James L. Marketos: George Horton: An American Witness in Smyrna. (PDF; 811 kB) (No longer available online.) Ahiworld.org, 2006, archived from the original on July 14, 2011 ; Retrieved March 11, 2009 .

- ↑ A United Nations document E / CN.4 / 1998 / NGO / 24 confirms the receipt of a letter from the International League for the Rights and Freedom of Peoples on February 24, 1998, entitled A people in continued exodus (these are the Pontic Greeks ; P. 3). For the letter A people in continued exodus : search United Nations documents .

- ^ Peterson, October 2008

- ↑ Valavanis, p. 24.

- ↑ Nikos Sigalas, Alexandre Toumarkine: démographique Ingénierie, génocide, nettoyage ethnique. Les paradigmes dominants pour l'étude de la violence sur les populations minoritaires en Turquie et dans les Balkans . In: European Journal of Turkish Studies . No. 7 , 2008 (French, openedition.org ): «le milieu de la revue Scholiastis dont est issu le journaliste et historien Tassos Kostopoulos»

- ^ Erik Sjöberg: The Making of the Greek Genocide: Contested Memories of the Ottoman Greek Catastrophe . Berghann, New York 2016, p. 46-47 (English, 255 pages).

- ↑ Hatzidimitriou, Constantine G., American accounts Documenting the Destruction of Smyrna by the Kemalist Turkish Forces: September 1922 , Caratzas, New Rochelle / NY 2005, p. 2

- ^ Bierstadt, September 2010

- ↑ Article Turks Proclaim Banishment Edict to 1,000,000 Greeks . In: The New York Times , December 2, 1922, p. 1.

- ^ Text of the Treaty of Sèvres .

- ↑ Bassioun, p. 62 f. in Google Book Search

- ↑ Geniki Statistiki Ypiresia tis Ellados (Statistical Annual of Greece), Statistika apotelesmata tis apografis tou plithysmou tis Ellados tis 15-16 Maiou 1928 . National Printing Office, Athens 1930, page 41. Quoted in Elisabeth Kontogiorgi: Population Exchange in Greek Macedonia: The Forced Settlement of Refugees 1922-1930 . Oxford University Press , 2006, ISBN 978-0-19-927896-1 , pp. 96, footnote 56 .

- ↑ p. 2 (PDF; 350 kB): “In 1923, the provisions of the Treaty of Lausanne left some 106,000 ethnic Turks in Thrace. The ethnic Greek minority of Istanbul […] has also shrunk in size […] from 110,000 in 1923 to an estimated 2,500 today. "

- ↑ Gilson, George. “ Destroying a minority: Turkey's attack on the Greeks ( Memento June 17, 2008 in the Internet Archive )”, book review of (Vryonis 2005), Athens News , June 24, 2005.

- ^ Human Rights Watch 1999

- ↑ Ascherson, p. 185.

- ↑ Constantine G. Hatzidimitriou: American Accounts Documenting the Destruction of Smyrna by the Kemalist Turkish Forces: September 1922 , New Rochelle, New York: Caratzas, 2005, p. 1.

- ^ Morgenthau [year?], P. 153.

- ^ Mark Mazower: The G-Word . In: London Review of Books . tape 23 , no. 3 , February 8, 2011, p. 19th ff . ( The G-Word [accessed May 1, 2011]): “But these deportations were on a relatively small scale and do not appear to have been designed to end in their victims' deaths. What was to happen with the Armenians was of a different order. "

- ^ Ferguson (2007), p. 182.

- ↑ Dominik J. Schaller, Jürgen Zimmerer: Late Ottoman genocides: the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire and Young Turkish population and extermination policies . In: Journal of Genocide Research , Volume 10, Issue 1, March 2008, pages 7-14.

- ^ Tatz (2003), p. Xiii. Original quote: to achieve its ninety-five-year-old dream of becoming the beacon of democracy in the Near East

- ^ Negotiating the Sacred: Blasphemy and Sacrilege in a Multicultural Society , Elizabeth Burns Coleman, Kevin White, p. 82.

- ↑ spending 2645/1998 and 2193/1994, the Official Journal of the Hellenic Republic.

- ^ Cyprus Press Office, New York City.

- ↑ Office of the Prime Minister, Directorate General of Press and Information: Turkey Denounces Greek 'Genocide' Resolution ( Memento of June 29, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) , September 30, 1998 (accessed February 5, 2007).

- ^ Robert Fisk : Athens and Ankara at odds over genocide. In: The Independent. February 13, 2001, accessed May 14, 2014 .

- ↑ Motion 2008/09: U332 Genocide of Armenians, Assyrians / Syriacs / Chaldeans and Pontiac Greeks in 1915. (No longer available online.) Riksdag , March 11, 2010, archived from the original on July 9, 2011 ; Retrieved March 12, 2010 . [URL out of date]

- ↑ The Greek Genocide 1914-23: Memorials ( Memento of 25 May 2012 at the Web archive archive.today ) Retrieved on 18 September, 2008.