Katzenau internment camp

The Katzenau internment camp near Linz existed during the First World War . It was used to accommodate civilians from states that were at war with Austria-Hungary , but also “unreliable” members of the Danube monarchy. These were mainly "imperial Italians" and "suspicious natives" of Italian nationality.

To the prehistory

After Italy entered the war on the side of the Entente Powers on May 23, 1915, the military authorities of the Danube Monarchy quickly ordered the internment of all “Imperial Italians” (members of the Kingdom of Italy) remaining in the national territory. At the same time, Italian-speaking residents suspected of irredentism from Welschtirol / Trentino , but also from the Austrian coastal region and Dalmatia, were arrested and sent to internment camps or confinement stations .

Due to Italy's dubious attitude towards entering the war, these measures had been prepared some time in advance and in some cases were carried out with excessive severity and open hatred.

In addition, for strategic military reasons, the civilian population was evacuated from the border areas with Italy and distributed to the inner Austrian crown lands via the two so-called "pearlization stations" in Salzburg and Leibnitz. Settled partly in localities (up to Bohemia and Moravia), the destitute majority of the refugees found themselves accommodated in various camps. This is especially true in Styria (Wagna near Leibnitz) as well as Upper (Braunau) and Lower Austria (Bruck an der Leitha, Gmünd, Pottendorf-Landegg, Mitterndorf , Steinklamm ).

As a "milder form of internment", Konfinierung (exile) has been used since the beginning of the war . In particular, financially strong people with a low risk of escaping could find accommodation in private quarters, but had to pay for this as well as for food themselves. They were allowed to move freely within certain areas and at certain times, but had to report regularly to the police or authorities and submit their correspondence to them. The largest confinement stations were in Upper and Lower Austria (Drosendorf, Groß Siegharts, Heidenreichstein, Linz, Oberhollabrunn, Pulkau).

Those destined for internment also ended up in camps, mainly in Upper and Lower Austria . For example, imperial Italians and politically suspicious Italian-speaking Austrians mainly in Katzenau and initially also in Göllersdorf and (until October 1915) Steinklamm (in the Pielachtal), but also in camps in Drosendorf , Enzersdorf im Thale, Hainburg, Mittergrabern, Raschala, Sitzendorf an der Schmida, Sittmannshof or Weyerburg.

The warehouse

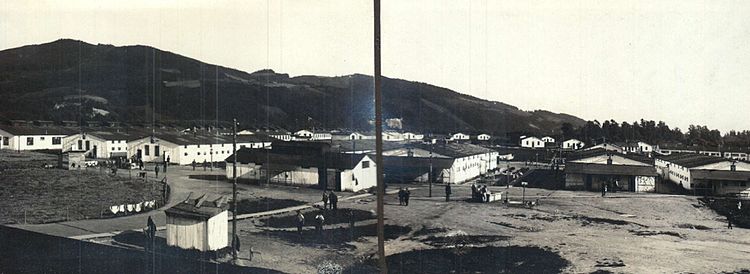

Located on an area of around 400 × 300 m on the right bank of the Danube near Linz, a barrack camp already existed in Katzenau before 1915, which was initially used as a military training area and from summer 1914 as accommodation for Russian prisoners of war. Cleared and disinfected after a typhus epidemic , it was used as an internment camp for civilians when Italy entered the war. The 38 wooden barracks that existed when the first Trentino and Imperial Italian internees arrived (on May 23, 1915) were expanded by 20 in the first few months. The camp command was housed in the only brick building.

administration

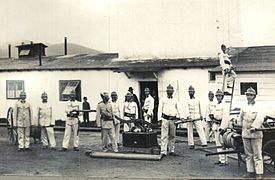

Although the camp Katzenau was directly in civil administration of the governor's office of Linz, but in the last instance the war monitoring office, a real military state police facility in the War Office. A Baron von Reicher was appointed camp manager until mid-October 1917, followed by an AJ Singer, and finally (from June 1918) a Mr. Seifert. The guards, however, were provided by the military authorities, which contained the potential for complaints and conflicts.

Occupancy

The number of internees in the Katzenau camp can be reconstructed to some extent on the basis of the registry lists that have been received, although the permanent arrivals and departures make it difficult to determine a total. The camp was a transit station for around 5000 “unfit for military service” Imperial Italians (women, children, old men) who were deported to Italy via Switzerland with the help of the Red Cross. There were also numerous transfers of Imperial Italians to Katzenau from other internment camps. The number of domestic internees, on the other hand, was constantly on the move, as they were transferred to confinement centers and assigned to disciplinary companies of the military. In addition, an increasing number of internees were subordinate to the Katzenau camp, but were housed outside (mostly in Linz) for work.

A total of around 16,000 to 17,000 people were interned in the Katzenau camp for a shorter or longer period of time, around 1,750 to 2,000 of them Italian-speaking Austrians.

The highest level of occupancy in the camp was only briefly reached at around 4500 people (end of November 1915), as was the highest number of internees subordinate to the camp at almost 10,000 (end of February 1918). The proportion of internees housed outside the Katzenau camp for work increased (around 700–1000) from around 23% in August 1915 to (around 5,800) two thirds of all people placed in the camp at the beginning of August 1918.

The majority (approx. 80–90%) of the permanently interned consisted of Reich Italians capable of military service, ie men between the ages of 18 and 50 years. They were mainly composed of “lower social classes”, were seasonal workers or day laborers who had stayed in the Danube monarchy for a longer or shorter period or were even born here.

In contrast to this, the “suspect natives”, that is, Trentino and Italians from Trieste and the coastal region, came from almost all of the bourgeois and socially higher classes. Among them were for example former members of the Reichsrat or Landtag, mayors, lawyers, doctors, priests, civil servants, professors, teachers, students, but also many merchants, craftsmen and innkeepers.

In addition to these two main groups, around 300 Romanians and Serbs and around 100 English and French were interned in Katzenau at times.

Overall, the proportion of women was mostly below ten percent, but it was significantly higher among residents.

The national groups, including Imperial Italians and Italian-speaking domestic internees, were housed in separate barracks from the start. The latter not only because of their different legal, but also social status.

The genders were for the most part strictly separated, men and women mostly relegated to their own, specially fenced-in storage areas; there were only a few family barracks. Following the social differences, there were also barracks for old, young, clergymen and nuns, as well as doctors, wealthy and intellectuals.

Camp life

The camp's infrastructure was initially completely inadequate. In addition to the far too few straw sacks for sleeping, the diet was also extremely poor. The chaos was partly caused by the large number of imperial Italians incapable of military service, who initially kept arriving in Katzenau, only registered here and then soon forcibly repatriated via Switzerland to Italy.

Located in the middle of the flooded area of the Danube and without any tree cover, the heat in particular was another major problem during the first few summer months.

The construction of additional barracks and infrastructural improvements eased the situation. The dismissal of the exploitative private canteens and self-sufficiency by an internal committee initially raised the nutritional situation considerably. But from the end of 1916 the food supply in general and with it in Katzenau came to a head again and even the warehouse had to be converted into a potato field.

Combating Irredentism

Since the beginning of the war, the powers of the Austrian military have been significantly expanded by an imperial decree, and the Austrian military authorities have played a central and inglorious role in the repressive "fight against irredentism". The preserved pearlescent sheets reflect the inadequate legal basis and mostly inadequate evidence procedures for the domestic internees who were initially suspected not infrequently for no reason. Quite a few of those who were finally (militarily) prosecuted were therefore acquitted (but remained interned). The impression is quite justified that the internment should primarily serve to prevent possible “irredentist” activities, while accepting blatant injustice. This contributed to the "alienation" of many of the former Habsburg loyal Trentinians.

On the other hand, some avowed irredentists may also experience internment as a relief compared to a (perhaps more appropriate) prison stay.

Many of the interned imperial Italians were indifferent to the national ideals of the irredentists and negative about Italy's entry into the war on the side of the Entente powers, as they lost their opportunities to earn a living and, in many cases, a second home. Some of them “fit for military service” may therefore have preferred internment - despite all the hardships - to being called up for military service in the Italian army.

Military service

Samples were repeatedly held among the Austrian internees. The men between 18 and 50 years of age who were found to be fit were called to arms (well over 200 in total) and assigned to so-called disciplinary companies, where they were subjected to special supervision but also to persecution and harassment.

job

The government was careful to recruit workers for the war economy and industry, but formally there was no work force in the Katzenau camp. In order not to be dependent on the meager, inadequate food in the camp, a large number of the internees were practically forced to go to work. However, the costs for the security personnel and food expenses were deducted from the wages, because every wage earner automatically lost the right to state support. The proportion of workers housed outside the camp rose from around 23% in August 1915 to around 66% in August 1918.

Supported by the administration, various work opportunities in the form of handicrafts (tailors, shoemakers, barbers, carpenters, etc.) or services (laundresses) also developed in the camp itself. Small shops and restaurants were also installed in the form of private entrepreneurship or a kind of “joint venture” in cooperation with merchants from Linz. These were, of course, mostly frequented by the financially better off internees.

Packaging

In order to reduce storage costs, internments were repeatedly converted into confinements in Katzenau from the summer of 1915 . The War Surveillance Office reserved the right to make decisions, Linz, Oberhollabrunn and Drosendorf in particular were considered as consolation sites.

Dismissal of residents

In December 1916 , Emperor Charles I , who came to head Austria-Hungary in November 1916 , issued an extensive amnesty for political offenses. At the same time a revision of the internment and confinement was ordered. This practically resulted in the release of most of the “suspect nationals” interned in the Katzenau camp between March and May 1917, but around a third was assigned in (light or strict) confinement.

But the return / repatriation of the “free” failed because of the enormous supply problems in the narrow war zone, but also because of the resistance of the Lieutenancies in Innsbruck and Trieste, so that most of them had to wait for the fighting to end as refugees.

Dissolution of the camp

The Katzenau camp existed until the end of the war and more than 8,000 internees were subordinate to it almost to the end, more than 90% of them Reich Italians and the majority (approx. 67%) housed in Linz for work. No reports have survived of the liquidation of the camp itself.

Rating

The Katzenau camp gained importance and publicity primarily because of the political internees, although these were numerically far in the minority. Well-known personalities and a larger group of prisoners from educated classes - especially from Trentino - drew the attention. And so Katzenau soon mutated into a (often nationalist, highly stylized) symbol for the oppression of the Italian minority in the Danube Monarchy, which was to find its “redemption” in the annexation of the affected areas by Italy. In the same context, the evacuation of the Italian-speaking population from the border areas was often discussed.

With historical distance, the nationalistically absorbing “memoralism”, which is mostly based on biographical evidence, is increasingly relativized. The justified anger over the injustice of so many domestic internees should not hide the fact that the social situation of the foreign civilian internees in Katzenau was significantly worse. In many cases, this also applied to refugees from the evacuated areas in camps and - with increasing duration of the war - even to the local population.

photos

literature

- Claudio Ambrosi: Vite internate. Katzenau, 1915-1917. Fondazione Museo storico del Trentino, Trento 2008, ISBN 978-88-7197-107-0 ( Pubblicazioni della Fondazione Museo Storico del Trentino. = Quaderni di Archivio trentino ) 18.

- Mario Eichta: Braunau - Katzenau - Mitterndorf 1915–1918. Il recordo dei profughi e degli internati del Trentino. = Memory of the refugees and internees of Trentino. Persico, Cremona 1999, ISBN 88-87207-07-0 ( Collana Storica ).

- Claus Gatterer : enmity. Italy - Austria. Europaverlag, Vienna et al. 1972, ISBN 3-203-50404-9 ( European perspectives ).

- Oswald Haller: The Katzenau internment camp near Linz. The internment and confinement of the Italian-speaking civilian population of Trentino at the time of the First World War . Dipl.-Arb. Univ. Vienna, Vienna 1999.

- Diego Leoni, Camillo Zadra (ed.): La città di legno. Profughi trentini in Austria 1915-1918. Fondazione Museo storico del Trentino et al., Trient et al. 1995.

- Reinhard Mundschütz: Internment in the Waldviertel. The internment camps and stations of the BH Waidhofen an der Thaya 1914–1918 . Diss. Univ. Vienna, Vienna 2002.

Individual evidence

- ↑ These are in the Austrian State Archives / War Archives / Central Office / War Ministry / War Surveillance Office / Cardboard 282.

- ↑ See: Claudio Ambrosi: Vite internate. Katzenau, 1915-1917. Trient 2008, p. 51 f.

Coordinates: 48 ° 18 '52 " N , 14 ° 19' 4.4" E