Dromos (music)

Dromos ( Greek δρόμος , "way"), plural dromoi (δρόμοι), sometimes synonymous taksimi (ταξίμι, from Turkish taksim ) and makami (from Arabic maqam ) is a modal scale in urban Greek folk music . In Greek popular music ( laïkoí ) the scales are called laïkoí dromoi (Λαϊκοί δρόμοι). Dromoi also form the tonal basis of the Rembetiko musical style(ρεμπέτικο). The tone scales, which come from oriental musical styles, have evolved into independent systems through contact with the harmonic tone systems of Central and Western Europe.

In Greek popular music, a distinction is made between western ( élafro ) and eastern ( varý ) currents , the western one being based more on functional harmony (dominant-subdominant system), the eastern one on modal melodies borrowed from the Arabic maqam systems.

A meaningful division of the Greek scales is difficult, as it can be based on many criteria. In this article it is done after the construction of the lower pentachord of each scale, a division that is also used in the maqam theory. According to this classification, besides major and minor scales, one can determine above all Phrygian, Lydian, Locrian and alternating scales. The designation according to church modes is not entirely correct; it serves only for a more detailed illustration. All scales are given with the root D, because on the one hand there are no double # ‚or double flat's, on the other hand because D is the root of the three-stringed long-necked lute bouzouki , the main instrument of rhembetiko and laikó music. The tone designation is chosen internationally, ie H is noted as "B", B as "Bb".

Origin and name

Most of the Laïkí Drómi go back to the Maqamat. They are partly named after personal names (Hüşşeyni), partly according to regions (Sabáh). Turkish terms are mainly used, but under certain conditions there are also Arabic (e.g. Bayati).

Sometimes there are several names for a scale:

For example: Nikríz is also called Pimenikós, Roumanikós or Souzinák.

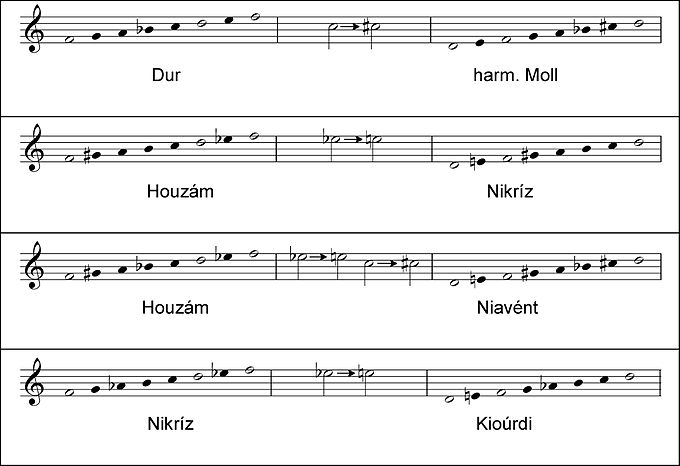

Sometimes scales have changed too.

For example: Niavént is a pure minor in Turkish, but Gypsy minor in Greek.

Sometimes there are multiple scales for a name.

For example: Houzám

The Greek scales are only a small part of the diversity of the Maqamat. Therefore, variations are possible within a name that would already have a different name in Turkish.

For example: All scales in the Bayati family are called Ousák in Greek, whereby Uşşaq is just one of many Bayati scales. This phenomenon results from the simplification of the tone intervals to the tempered 12 semitones, which are also fixed by frets on most instruments of popular Greek music.

Some Drómi do not have Turkish names, but Italian ones. These are the scales that we also use: major (matzóre) and minor (minor) and their variants. These scales also exist in the Maqam system (there they are called Çargar and Buselik), but in Greece they belong to the western system and are harmonized in this way.

The Drómi (Klímaka)

structure

The drómi consist of two parts: a pentachord and a tetrachord, with the top note of the pentachord also being the bottom of the tetrachord.

The lower pentachord indicates the mode, the upper tetrachord a more detailed character.

Basically, the scales are felt at intervals on the lowest note (root note). That is why the solos ( Taqsim ) do not improvise over harmony sequences, but only over a keynote. The individual tones are therefore reproduced as intervals.

The basic structure of every drómou is:

Framework of prim, fourth, fifth, octave, in between major or minor seconds, third, sixth and seventh. In some scales there are alternations of seconds, fourths, fifths and octaves.

They are reproduced here as follows:

g = large, k = small. ü = excessive, v = reduced.

Basic scales

The following scales are given as the most important Drómi:

Extended scales

Many scales have relatives with Arabic pitches. These are often reproduced as quarter tones, but are in truth their own interval structures that result from integer overtone ratios and rather belong to the third tone range. They are shown here with an n (neutral).

Furthermore, a number of variants can be read out for many basic scales, some of which can be derived from the direction of movement of the scale (e.g. Kioúrdi), and partly from its use in countless songs (especially Houzám). This results in the following overall table:

Direction of movement

Maqamat not only have a store of clay, but also a direction of movement. That means, they have a slightly different set of notes upwards than downwards. An example that also exists in Central Europe is melodic minor. Neutral intervals are often played around with the help of directions of movement. There are the following options:

1. g up, k down.

2. k and g up, g and k down.

Often only the directions of movement reveal the differences between the scales (Rast-Huséïni or Moll-Melodisch Moll)

Scales with directions of movement:

Sub-scales

With many scales, two extensions are often used in order to emphasize the keynote more strongly. Usually two or four of the tones given here are used:

Major, Houzám: ABB # C #;

all others: GABC

By using the sub-scales and formulas for the direction of movement, some variants have become established, some of which are almost exclusively used.

This includes the following variant of Houzám:

(B # C #) DE # F # G # ABCDCBAGF # E # D.

What is striking here is the small seventh, which comes from the downward direction of movement.

There is another very common phrase in Sabáh: the octave reduced by the direction of movement can be decorated with up to four additional tones above, resulting in the following tone stock: (GABC) DEF Gb A Bb C Db (EF Gb A)

Related scales

Parallel scales

Similar to our major-minor relationship, there are also many parallels with the Dromi, in that scales with the same tone reserve are superimposed on one another. The character of the new Dromou is created by defining the new basic tones. There are tone stocks in which the scales can be exchanged at will, but also fixed tone stocks in which there is a main scale and several upper parallels. The most common parallels are shown here.

Interchangeable basic keys (note stock is repeated per octave, i.e. every scale can be the main scale)

Fixed basic keys (note supply changes per octave, i.e. only the lowest scale can be the main scale)

Parallels with changing guiding or sliding tones

Further relationships can be formed by changing a tone within parallel scales. Most commonly used is the change from C to C # between major and harmonic minor. This change comes from the western systems and arose from the use of a major dominant in a minor key.

Familys

The scales that have the same lower pentachord can be classified as families. This also includes the scales for which the same sound supply results from the direction of movement.

| Major scales: | Madzore |

| Rest | |

| Tabahaniótikos | |

| Houséïni (upwards) | |

| Highly aged major scales: | Houzám |

| Sengah | |

| Minor scales: | Minor |

| Armonikó Minóre | |

| Melodikó Minóre | |

| Houséïni (downwards) | |

| "Arabic minor" scales: | Hitzáz |

| Hitzaskár | |

| Elevated minor scales: | Nikríz |

| Niavént | |

| Doric scales: | Kioúrdi (upwards) |

| Melodikó Minore (upwards) | |

| Phrygian scales: | Ousák |

| Bayati (Neva Ousák) | |

| Alternate minor scales: | Sabah |

| Nevesér | |

| Locrian scales: | Kartsigiár |

| Kiourdi (downwards) |

Tabahaniótikos and Sengáh are also often referred to as related, since they use a pentachord on a major scale and a tetrachord on a minor scale.

harmonization

Greek popular music is harmonized. In the case of scales from whose tones the dominant and subdominant can be formed, the harmonization of the functional harmonic follows. One speaks here of the western system. For scales in which this is not possible, one orientates oneself according to reference tones within the scales or alternates with parallel scales. Here one speaks of the eastern system. In general, harmonization must support the character of the scale.

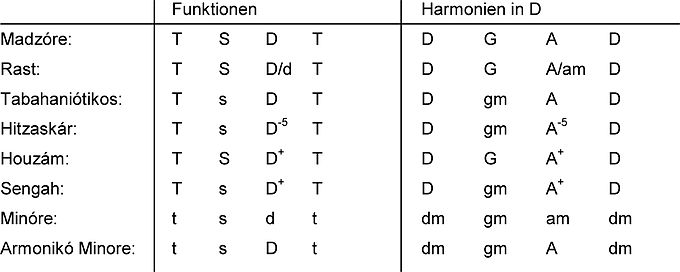

Harmonization according to functions

In this harmonization, quint relationships are formed:

Tonic (basic key) = T, dominant = D, subdominant = S. The tone gender is determined by the tones of the scales and must not be changed.

Easy harmonization

Only the simple cadences in the respective tone gender are given.

Harmonization with replacement chords

With some scales no dominants can be formed. Therefore one switches to substitute chords. D-Hitzáz uses Eb major as the dominant and D-Ousák uses C minor as the dominant. These chords can be derived harmoniously.

Even with a pure minor you can use a replacement chord if you want it to sound more eastern.

Harmonization according to reference tones

In this form of harmonization, pitches that are important within the scale are harmonized. It is possible to set the entire scale under a single basic harmony, or to use the respective tones to create new harmonies that do not necessarily have to have tones of their own. This results in modulations in parallel scales. The tones of a scale are given as steps, possible harmonies are below.

Use of the dromi in music

From Rhembetiko to Laiko

Very early Rhembétiko recordings often reveal Turkish or Arabic maqamat. Therefore, they sometimes have misleading names. Rhembetico compositions from the 1930s, on the other hand, provide a very precise representation of the scales. In the early Laïkó Tragoúdi of the 50s, the distinction was made between Varý and Élafro. Élafro (= happy, easy) is easy to harmonize; Western major and parallel minor scales predominate. Varý is both difficult in terms of effect and difficult to harmonize, as the eastern scales predominate here. Especially in the 50s and 60s, pieces with many modulations and mode changes were created here. Later the focus shifted to Hitzáz and Ousák, who still play the leading role in the Varý Laïkó Tragoúdi today.

Frequency of the scales

If one takes a cross-section of bouzoúki music from the 1920s to the present day, the most common are major, houzám; harmonic minor, Hitzáz and Ousák. Pireótikos, Tsiggánikos and Houséïni are the least common. Tsiggánikos and melodic minor are mostly only used in conjunction with other modes. Tsiggánikos is mainly used in Hitzás-Taqsimen, but more rarely as a variation of Hitzás or Hitzaskár songs. Melodic minor is often used in interludes or passages within pieces in harmonic minor, in the variant with a minor seventh (Doric variant) it is often found in its pure form.

Sound samples

The sound samples consist of the ascending and descending scale, played on the bouzoúki, a taqsim and an excerpt from the Greek rhembetiko pieces given below. These pieces are now part of the traditional song repertoire of Greece.

Matzore

O Kaimos

Rest

Mónos Mou Periplaniéme

Tabahaniótikos

Perasména Xehasména

Hitzás

Nýhtose Horís Feggári

Hitzaskár

Giá Tin Aponiá Sou

Tsingánikos

I Róza I Naziára

Pireotikós

O Memétis

Houzám

Brós To Rimagméno Spíti

Sengah

O Sakafliás

Houséïni

Piós Soú'pe Pos Dén S'Agapó?

Nisiotikó Minóre

Thalassáki

Armonikó Minóre

Frankosyrianí

Melodikó Minóre

O Psarás

Kioúrdi

Begléri Ke Mahéri

Kartzigiár

O Dimitrákis O Psarás

Nikríz (Pimenikós)

O Thermastís

Niavént

Áris Velohiótis

Ousák

Més Tis Pentélis Ta Vouná

Néva Ousák (Bayáti)

Poú'soun Mágka To Himóna?

Sabah

Ísouna Xypóliti

Nevesér

Ai-Voliótikos

Recorded by Christoph Roesler & Psaltrón

literature

- Arabic Musical Scales: Basic Maqam Notation by Cameron Powers; GL Design 2006

- Turkish Classical Music, The Lute and Makam Publishing House; Y. Landeck 2006

- Dimitris Boukouvalas: Learn Greek Bouzouki Music; Boukouvalas ed. 2010

- Analyzes of innumerable sound samples, as well as encounters with many Bouzouki players