Tx transform

tx-transform is an implementation of the so-called slitscan recording technique carried out by Martin Reinhart . It is a film technique that swaps the time (t) and one of the spatial axes (x or y) in the film. Normally every single film frame covers the whole room, but only for a short moment of time (1/24 of a second). With tx-transformed films it is exactly the opposite: Each film frame shows the entire time, but only a tiny part of the room - with cuts along the horizontal spatial axis, the left part of the image becomes the "before", the right part the "after" .

tx-transform is also the title of a short film (Austria 1998, 35 mm, Cinemascope, duration: 5 min.) that Martin Reinhart made together with Virgil Widrich , in which this technique is used for the first time.

Emergence

Since 1992 Martin Reinhart has been working on developing a process that, so to speak, turns the cinematic system of order inside out and thus makes it readable across the time axis. With tx-transform, sequences can be created in which the cinematic representation is no longer determined solely by the spatial presence of an object, but rather depends in its form on the complex interplay of relative movements. Objects in the film are therefore no longer defined as an image of a concrete existence, but as a state of affairs in time.

Cinematic representations of movement

When a stationary object is recorded, it does not matter in principle whether a temporal reversal, stretching or division is made during recording or playback, the result will always remain the same. Movement in the film is just recorded movement relative to the frame. “Relatively static” in this case means that the relationship between the object and the lens remains unchanged, that there is a rigid axis between the signal and the signal recording. From this it can be said that movement within the cadre boundaries is only perceived when either the object moves in relation to the camera or the camera moves in relation to the object, briefly when there is a relative movement.

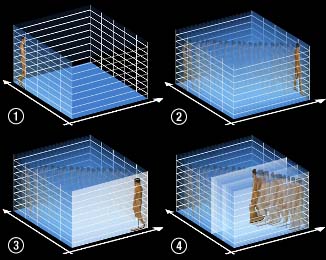

Especially with film, it is easy to illustrate that further movement is required to create an illusion of movement: the film has to run through the projector. The movement of the film knows only one direction - from the first to the last frame of a strip. This information structure along a temporal vector can also be thought of as stratification, and can be best illustrated by the shape of the flip book: In this children's toy, the illusion of movement is created by a rapid succession of individual time layers. The flip book contains, like the film reel, the entirety of all spatial aspects of movement and can be understood as an “information block”. Usually this block is scrolled through from front to back, along the time axis, in order to create the illusion of cinematic movement.

Movement representation in the tx transformation

tx-transform is also a section through this information block ", but not along the time axis, but along the spatial axis. At first glance, it may not seem very likely that these" spatial sections "can lead to legible images, let alone to comprehensible sequences of movements . But that is by no means the case. These "spatial sections" through the information block result in a number of amazing visual effects: Houses begin to move, heads grow out of themselves, moving trains become shorter and shorter with increasing speed and much more In contrast to conventional films, the definition of the camera or object movement is of substantial importance in tx transformations. In order to be able to use the material captured during the recording for the production of tx transformations, various parameters must be precisely adhered to and the various criteria in Relation to the relative movement between camera and object er be filled. The usual omission of unsuitable film parts (scrap) is not possible, since a single missing image in the source material would affect the effect of the entire sequence. The result of a tx transformation can appear completely abstract or completely realistic, depending on the type of recording.

The embodiment of the process in the software is protected by copyright. The European patent application EP0967572 A2 exists for the method.

Remarks

The TX transformation is an implementation or further development of the slit scan technology. Martin Reinhart's claim relates to the device and the software he developed. The above-mentioned patent thus relates to this particular implementation, since a “novelty claim” is required for patents per se, which in this case does not exist in full.

History

Slitscan film recording technology has its origins in the 1960s. Douglas Trumbull, Special Effects Coordinator for Kubric's 2001 epic - A Space Oddysey , used the interchanging of the space and time axes to create the famous “tunnel effects” towards the end of the film, and all without any computer technology. After that some filmmakers worked on and with this technique, especially in the experimental film area. This is how Zbigniew Rybczynski's film The Fourth Dimension (1988) was made.