African throwing iron

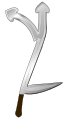

The African throwing iron is a sickle-like, often multi-bladed throwing or cutting weapon that was used in various cultures in Central Africa until the 20th century. Like the Australian boomerang , throwing irons that are suitable for throwing rotate around the center of mass in flight . In many cases, however, throwing irons are not actually suitable for throwing; they were used as a status symbol , primitive money or as a ritual object. The throwing iron as a multi-bladed throwing weapon occurs exclusively in Central Africa.

Designations

Central Africa's throwing irons are also known as throwing blades and throwing knives . In early publications, the terms Schangermanger or Tomahawk , actually an ax of the North American Indians, are used. Well-known regional names for certain throwing irons are Hunga Munga , Shongo and Kipinga , which are sometimes used as generic terms.

history

A further development of the throwing stick is often discussed as a possible origin of the throwing iron. However, this is controversial, as throwing sticks were sometimes used in parallel to throwing irons, such as. B. with the Ingessana on the Blue Nile on the eastern border of Sudan . The geographical origin is also controversial; some theories name areas south of Lake Chad in the Chari-Baguirmi region or between the tributaries Mpoko and Mbari of the Ubangi . Another theory assumes a development from the simpler-looking northern F-forms to the more complex-looking southern forms. From a technical point of view, however, the production of the northern types is no easier than that of the southern types.

Metallurgy has been practiced in Central Africa for over 2000 years, so it is possible that throwing irons were used back then; as no specimens from this period have been found so far, this is only a speculation. The fact that no archaeological finds have been made so far is also due to the soils of Central Africa, which conserve iron poorly. The oldest surviving specimens are estimated to date from the end of the 18th century. The American historian Christopher Ehret suspects that the first throwing irons were made in the second half of the 1st millennium AD and spread in the first half of the 2nd millennium. One of the few traditions from the pre-colonial period comes from the Cuban Federation . According to legend, King Shyaam Ambul Angoong united the Cuba in the 17th century after a long war and then banned the throwing iron shongo .

In the course of imperialism , a race for Africa took place between the European states from around 1870 , which only came to an end with the outbreak of the First World War . The colonialism altered and destroyed the central African culture, which also included the throwing iron.

With the interest of Europeans in African art, the throwing irons, which seemed bizarre to them, also became research objects and coveted collectibles or museum exhibits. The interests of the Europeans did not go unnoticed by the Africans, so at the beginning of the 20th century they made throwing irons for commercial export. These included imaginative commissioned work that had little to do with traditional throwing irons. On the other hand, some ornate shapes could only be made for personal use with modern, imported European tools. Also at the beginning of the 20th century, European scrap iron became available, which replaced traditional iron smelting. After the First World War, finished sheet iron was added that only had to be cut to size. Some recent specimens were made from these cheap materials. The last traditionally manufactured throwing irons are dated to the middle of the 20th century. While the unadorned models with weapon functions were left to decay, models with ritual and cultural functions had a far greater chance of survival.

Research history

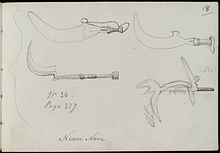

The earliest reports on the existence of throwing irons known to modern research were written by European travelers to Africa, such as the Welshman John Petherick (1861), the French anthropologist Paul Belloni Du Chaillu (1861) and the Italian botanist Carlo Piaggia (1865). The first examples reached Europe in the last quarter of the 19th century. Heinrich Schurtz wrote the first extensive scientific study of throwing irons in 1889, where he was particularly concerned with the developmental stages of the throwing wood up to the multi-bladed forms. In 1925, Ernest Seymour Thomas carried out an extensive classification of the various forms. In 1988 Peter Westerdijk continued his father's work in his dissertation and defined style provinces as a system of order.

description

An African throwing iron has several blades on a handle (in the lower area e.g. as a thorn with and without an ear, in the upper area as a wing, lip and / or crown), which are arranged approximately at right angles to the handle. The stem ends as a handle. The total weight is 300 to 500 grams. All parts of the weapon (handle, blades, handle) are flat. The larger northern F-types can be over 5 millimeters thick in some places, but in most cases these are up to 4 millimeters thick. The southern, "winged" types are thinner and usually 2 to 3 millimeters thick. The back is flat, while the front, the front side, is usually profiled. The cross-section is accordingly triangular, trapezoidal or curved inward. The weapon is made of iron or steel , but there are rare specimens that are made entirely of copper or brass .

Throwing irons built for throwing either have a bare handle (northern types) or their handle is made of light, elastic and yet robust materials, e.g. B. wrapped animal skin, plant fibers or metal wire. Non-flightable types often have a wooden handle.

There are many different forms of throwing irons. Ernest Seymour Thomas noted 18 forms, while Marc Leopold Felix derived five basic forms from the Latin letters (F, Z, E, Y, I). The procedure of using letters is criticized as being too simplistic, since not all forms are recorded.

function

As about the history of the origins and distribution of throwing irons, there are also various theories about their function. It used to be assumed that the throwing irons spread from the north to the south, taking on more complex shapes and gradually losing their functional properties as a throwing weapon and instead becoming more and more a ritual symbol. At least the gradual change in function is now considered refuted, as there are throwing irons for purely cultural purposes in the north as well as documented throwing weapons in the south.

Overall, the meaning of the throwing iron is only partially understood in many cultures.

weapon

In its function as a weapon, the throwing iron was used in combat and, to a lesser extent, in hunting. Archaeologically, however, it is difficult to prove a functional use as a weapon; Signs of wear and tear can only rarely be found that allow conclusions to be drawn about throwing or similar processes. According to Christopher Spring, use as a throwing weapon is only clearly documented by the Sara as ngalio (northern type) and by the Azande as kipinga (southern type).

Since there are no reliable eyewitness reports about the throwing technique, one has to rely on flight attempts or oral reports. The throwing irons of the F-type can be thrown up to 50 m, those of the winged type up to 60 m. However, the effective distance at which the opponent can be incapacitated is between 20 m (F-type) and 30 m (winged type).

There were different techniques for throwing:

- The thrower throws horizontally at about hip height, comparable to the throwing technique when jumping stones .

- The thrower throws horizontally at shoulder height, comparable to throwing a javelin . The large F-shaped throwing irons can be thrown successfully.

- The thrower throws horizontally at knee height in a flat path, comparable to a bowler throw . On hard ground, the throwing angle can be chosen to be even flatter, so that the throwing iron bounces off the ground several times like a rikoschett shot . This throwing technique is suitable for hitting the opponent's legs.

No African people used the throwing iron as their main weapon; usually this was the spear . Compared to a spear and arrow , the possible impact area is significantly larger, but this cannot be said of the overall effectiveness. The effective range against unprotected enemies is similar for all three weapons, but the enemies were rarely unprotected. Braided shields were predominant and these withstood the throwing iron, whereas a throwing spear could quite penetrate them. On the other hand, the throwing iron could turn around the shield with a favorable hit and hit the opponent behind it. Often the throwing irons were thrown as a "volley" by several warriors at the same time in order to make it difficult for the opponents to evade. Whenever possible, a warrior carried several throwing knives. So there were different ways of carrying, z. B. hung in the inside handle of the shield (with the Zande), strapped as a bundle around the waist or hanging in a quiver over the shoulder (with the Sara).

The throwing irons were also an effective close combat weapon. The spurs could serve as parrying elements and also allowed the enemy weapon to be jammed in order to snatch it from him. Some copies, e.g. B. the Gbaya, were not designed to be thrown.

In comparison, the arrow and spear were much easier to manufacture and with less rare materials with similar effectiveness. Because of its high value, the weapon was also used carefully. This apparent contradiction is explained by the psychological effect, especially in wars of conquest, when the weapon was unknown to the enemy. Schurtz often sees the purpose of a “threatening weapon”, which is rarely actually used. This is probably related to traditional African warfare. In addition to the rarer wars of conquest, there were often local skirmishes between neighboring settlements. It was not primarily about destroying the enemy. The fight was decided if one party fled. For example, the Zande did not completely surround their opponents, but left a gap through which the defeated opponent could escape.

Other functions

In addition to the function of a weapon, various functions are assigned to the throwing iron; many specimens were never designed as a weapon. Simple and unadorned throwing irons could also be used as a commodity or tool z. B. be used for slaughtering animals, for cutting or for chopping wood. Ornate specimens were so precious that they were rarely used as weapons. Basically, even simple models were valuable, if only because iron was a rare and expensive raw material.

Since iron was rare, it was used as a currency of exchange. In general, the local form as primitive money often follows the shape of the local utensils (e.g. Chinese knife money ). This is also the case with throwing irons: ordinary throwing irons as well as those specially made for the purpose were exchanged. These variants have changes, e.g. B. enlargements or reductions of elements or waiving the gloss-imparting polish. These changes probably had the purpose of making the objects of exchange easily recognizable as such. Probably the best-known primitive money based on throwing irons is the woshele from the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

In many cases they served as status symbols for power, wealth, social position or masculinity. In some societies the throwing irons are still considered part of the traditional male costume. The throwing irons also play a role as utensils in traditional dances . Men show their war and hunting skills in fighting dances. In some cultures the throwing iron represents a flash of lightning during the rain dance . It is known from western Darfur that women wear throwing irons during circumcision ceremonies . The Baganda used the throwing irons in initiations of boys into tribal society.

A veneration of certain forms as sacred ritual objects is also known. As a defense spell, they were placed in fields to protect the crops. It could be sworn on a throwing iron that lightning should strike a liar.

In addition, some throwing irons were used as a tribal symbol. They are well suited for this because they allow a wide variety of shapes and local blacksmiths could choose a special shape, which was then copied many times.

Manufacturing

Two different manufacturing processes were used to achieve the desired shape. In the case of fire welding , additional blades were welded to the main body. This is a difficult procedure and was mainly used to attach the center mandrel on the F-types. At the southern types, the form was rather piece by piece from the multiple heated blank out forged . Most of the surviving specimens received additional processing such as bows and decorations . Lines and patterns were hallmarked , incisions or cutouts were made or the surface was burnished (blackened). The blackening took place by burning off a mixture of oil and charcoal on the iron surface.

Forms and their distribution

Thanks to scientific research, the throwing irons can be assigned to the approximate area of origin according to their shape. An exact assignment to a tribe is difficult, since the weapons are custom-made and therefore often only differ slightly and the transitions of the styles are fluid. A geographical assignment is made more difficult because some tribes used several styles in parallel and because the throwing irons were not only used by the manufacturer due to trade or spoils of war. Some throwing irons, especially those of the northern group, were not made by the peoples themselves, but by specialized castes or tribes, such as the Haddad .

The coarsest subdivision is the north and south group. The limit is about 9 ° north latitude .

- The northern group is more elongated and has fewer blades; Found in Sudan , Nigeria and Chad . The shape and processing looks simpler than that of the southern group. Due to the shape and the center of gravity, the throwing iron can be carried on the shoulder.

- The southern group is smaller, has multiple and flatter blades; Occurs in a wide belt from Cameroon to the White Nile . The shape and processing seems more complex than that of the northern group.

Style boundaries are seldom clear; Overlapping areas where multiple styles have been found are common. There are also always mixed forms that cannot be clearly assigned to any style.

Northern or F type

Southeast of Lake Chad: Southeastern and northern Sara

The area is bounded in the northwest by Lake Chad and in the west by Logone . It mainly includes the south of Chad, but also neighboring countries.

The throwing irons are attributed to the southeastern and northern Sara , including Niellim, Tumak and Madjingay, who live east of the Logone River , and the Manga, Musgum , who live south of the confluence of the Shari and Logone rivers . Characteristic is a robust shape, the upper blade is curved and provided with a cutting edge. Several throwing irons can be carried in a kind of quiver (Figure B); these containers are only found in this area. The throwing irons are called ngalio in the area . There is evidence of military use in the Bornu Empire and in the Baguirmi Sultanate .

West of the Logone River: southwest Sara

The area is bounded by the Logone River to the east. It mainly includes the southwest of Chad and northern Cameroon.

The throwing irons are attributed to the southwestern Sara , including Laka, Ngambaye and Daye. Edged and thorn-like throwing irons, which appear light and fragile, are characteristic. There are no handles or wraps around the handles. It is unlikely that these throwing irons were used for any practical purpose (weapon or tool). Some of the throwing irons are venerated as relics among the Daye.

Southwest of Lake Chad: Kirdi

The area is bounded in the northeast by Lake Chad and in the east by Logone. It mainly covers the east of Nigeria and the far north of Cameroon.

The throwing irons of this area are mainly attributed to the Kirdi ethnicities, including Margi, Mafa (as mberembere or sengese ) and Fali. The F-shape is predominant in the area, but the shape becomes more ornate, as can be seen in the Margi specimens. The Sengese (Figure C) of the Mafa from the Mandara Mountains is even further removed from the F-shape. The top half is twisted and resembles the number 3 . In the middle of the first bend there is a short, pointed spike. Often fastening eyes are attached to the chain or cords can be attached.

Chad

The area is bounded in the north by the Tibesti and roughly covers the national territory of Chad. These forms were particularly widespread in the regions of Wadai and Ennedi (there with the Zaghawa ) and in the Tibesti Mountains (there with the Teda ). The averse central spine is characteristic; with other throwing irons of the northern group, this is usually attached at right angles. In terms of shape, a bird could be represented, but this has not been proven.

Darfur: Masalit and Fur

The area covers the entire Darfur region .

The style of the throwing irons of the Masalit and Fur from Darfur is closely related to the style from Wadai and Ennedi in eastern Chad. The throwing irons from Darfur are lighter and more finely detailed. The Fur language names the Masalit throwing iron Zungan dowi (for cock's tail) and the Fur throwing iron sambal

East Sudan: Ingessana, Nuba and Nuer

The area includes Kordofan in the west and mainly includes the south-east of Sudan.

The throwing irons are attributed to the Ingessana from southeast Sudan, the Nuba from Kordofan and Nuer from South Sudan (Figures A – D). It is characteristic that the shapes of these throwing irons are based on shapes from the animal kingdom. In the Ingessana, the snake shape is called sai and the scorpion shape is called muder . The throwing irons are worn as part of traditional costume in this area .

Sudan is also the origin of blunt copies of southern throwing irons (Figures E – F), which were made over a short period of time, but in large numbers, in the late 19th century. The specimens are punched from sheet metal and are decorated with calligraphic etched quotes from the Arabic Quran . The mixing of the Islamic and the traditional cultural aspects is remarkable, as the throwing iron was actually considered primitive and pagan to the Muslims. These imitations were given out as favors by Sudanese slave traders to local tribal leaders in Central Africa, but were also found among the Mahdists who had slaves from Central Africa in their ranks. There they were probably used as status or rank symbols.

Southern or winged type

Eastern Cameroon: Gbaya

The area includes the east of Cameroon, the west of the Central African Republic, as well as the north of Gabon and the Republic of the Congo.

The throwing irons are mainly attributed to the Gbaya and related groups. The throwing irons mentioned above cannot be used as throwing weapons, but they are still counted as throwing irons. The Gbaya-type is similar to the northern F-types, but more of a mixture of the F- and I-shape. The middle spur is on the other side than the northern F-types.

Eastern Ubangi Basin and South Sudan: Azande and Your Area of Influence

The area includes the eastern catchment area of the Ubangi River (north of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and east of the Central African Republic) and South Sudan . While Spring treats the area as a whole, Westerdijk and Felix divide it into three overlapping areas.

This area contains the typical Z (Figures A – D) and Y shapes (Figure E). These are attributed to the Azande and other peoples in their area of influence, including Ngbandi , Nzakara or Banda (as onto or ondo ). The Z-shaped kipinga or kpinga of the Azande is considered to be the best known and best studied throwing iron in the Ubangi area. The Azande use the throwing iron z. B. by field studies by Edward E. Evans-Pritchard as proven. The warriors used disc-like suspensions in their shields to secure the throwing irons and keep them handy in battle.

Western Ubangi catchment area

The area comprises the eastern catchment area of the Ubangi River (north of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and west of the Central African Republic) as well as South Sudan . While Spring generally treats the area as southern throwing irons, Westerdijk and Felix divide it into three further, overlapping areas.

The throwing irons are attributed to the Ngbaka (as za ), Yangere, Manza, Mbaka , Ngombe and Mbugbu, among others .

In this area you can find the typical cross or E (Figures D, E) as well as Y (Figure G) and many other mixed forms. There is a lack of knowledge in this area, both about the exact tribe allocation and about the respective function and meaning of the throwing irons. Among the Mbaka, the throwing iron is also known as a cult object that is supposed to work against magic. Otherwise, Stone assumes that function and meaning are similar to the Zande area of influence.

South Cameroon, Gabon and the Republic of the Congo

The area includes the south of Cameroon, Gabon and the Republic of the Congo.

South of the Gbaya style, throwing irons with protruding, leaf-shaped blade tops are found (Figure A). These are attributed to the Njem and the Kwele .

Further south, the upper side of the blade changes to a stylized bird's head (Figure B), which is why the throwing irons are also known as bird's head knives . These throwing irons are mainly attributed to the Kota (as musele ) and Fang (as onzil ) from Gabon . Mostly there is a triangular hole in the middle part, which is supposed to represent the bird's eye. Most of the specimens are made of iron, but there are also some made of copper. Some knives have rectangular sheaths made of wood or sheet brass. Some specimens do not show a bird's head, but a stylized fish (Figure C). The knives were used as status and ritual objects.

Media reception

Throwing irons are sometimes used as an exotic stylistic element in the media, for example in the fantasy television series Buffy - The Vampire Slayer and in the adventure film The Mummy Returns .

literature

Older representations

- Richard Francis Burton : The Book of the Sword. Chattoo and Wingus, London 1884, pp. 36-37; Text archive - Internet Archive .

- Henry Swainson Cowper : The Art of Attack. Being a Study in the Development of Weapons and Appliances of Offence, from the Earliest Times to the Age of Gunpowder. Holmes, Ulverston 1906. (Also Reprint: 2008), ISBN 978-1-4097-8313-8 , pp. 153, 169; Text archive - Internet Archive . ( archive.org ).

- Leo Frobenius : African knives. In: Prometheus. Illustrated weekly on the advances in trade, industry and science. Mückenberger, Berlin Jg. 12, 1901, No. 48 = 620, pp. 753-759.

- Paul Germann: African throwing irons and throwing sticks in the Ethnographic Museum in Leipzig. In: Yearbook of the City Museum for Ethnology in Leipzig. Vol. 8, 1918/21 (1922), pp. 41-50.

- Throwing iron . In: Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon . 6th edition. Volume 20, Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig / Vienna 1909, pp. 771–772 .

- Heinrich Schurtz : The throwing knife of the negroes: A contribution to the ethnography of Africa . In: International Archive for Ethnography. Trap, Leiden, etc. a., Vol. 2, 1889, pp. 9-31; archive.org (The board with 60 drawings is between pages 80 and 81).

- Ernest Seymour Thomas : The African Throwing Knife. In: The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. Vol. 55, Jan.-Jun. 1925, pages 129-145.

Newer representations

- Johanna Agthe, Karin Strauss (texts): Arms from Central Africa. Museum für Völkerkunde, Frankfurt am Main 1985, ISBN 3-88270-354-7 , pp. 22-24.

- Johanna Agthe [and a.]: Before the guns came. Traditional weapons from Africa. Museum für Völkerkunde Frankfurt am Main 1985, ISBN 3-88270-353-9 .

- Tristan Arbousse Bastide: Traditional weapons of Africa. Billhooks, Sickles and Scythes. A regional approach with technical, morphological, and aestetic classifications. Archaeopress, Oxford a. a. 2010, ISBN 978-1-4073-0690-2 . ( British archaeological reports. International series. 2149).

- Jan Elsen: De fer et de fierté. Armes blanches d'Afrique noire du Musée Barbier-Mueller . 5 Continents Editions, Milan 2003, ISBN 88-7439-085-8 .

- Marc Leopold Felix : Kipinga. Throwing Blades of Central Africa. Throwing blades from Central Africa. Galerie Fred Jahn, Munich 1991.

- Werner Fischer, Manfred A. Zirngibl , Gregor Peda, David Miller: African weapons. Knives, daggers, swords, axes, thrown weapons. Prinz, Passau 1978, ISBN 3-9800212-0-3 .

- AM Schmidt, Peter Westerdijk: The Cutting Edge. West Central African 19th century throwing knives in the National Museum of Ethnology Leiden. Leiden 2006, ISBN 978-90-5450-007-0 .

- Christopher Spring : African Arms and Armor. British Museum Press, London 1993, ISBN 0-7141-2508-3 .

- H. Westerdijk: IJzerwerk van Centraal-Afrika. Museum voor Land- en Volkenkunde Rotterdam, De Tijdstroom, Lochem 1975, ISBN 90-6087-939-2 .

- Peter Westerdijk : The African Throwing Knife. A style analysis. Utrecht 1988, ISBN 90-90-02355-0 . Utrecht, Univ., Diss.

- Manfred A. Zirngibl , Alexander Kubetz: panga na visu . Handguns, forged cult objects and shields from Africa. HePeLo-Verlag, Riedlhütte 2009, ISBN 978-3-9811254-2-9 .

Web links

- Christian Warnke (lecture, autumn conference of the Association of Friends of African Culture, Georg-August University, Göttingen): African throwing irons - social, economic and cultural function - GO-2008HT-09 . 2008

- Overview at memoire-africaine.com (French)

- Overview of African throwing irons at ogun.qc.ca

Individual evidence

- ↑ Felix 1991, p. 13.

- ↑ Throwing iron . In: Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon . 6th edition. Volume 20, Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig / Vienna 1909, pp. 771–772 .

- ^ Richard Francis Burton : The Book of the Sword. 1883, p. 36.

- ↑ a b Hunga Munga. Pitt Rivers Museum

- ↑ Spring 1993, p. 77.

- ↑ a b c d e Spring 1993, p. 70.

- ↑ a b Felix 1991, pp. 17-20.

- ↑ Christopher Ehret : The Civilizations of Africa: A History to 1800. James Currey Publishers, 2002, ISBN 0-85255-475-3 , p. 340.

- ↑ a b Spring 1993, p. 68.

- ↑ a b Westerdijk 2006, p. 41.

- ↑ Spring 1993, p. 79.

- ^ Robert Joost Willink: Stages in Civilization: Dutch Museums in Quest of West Central African Collections (1856-1889). CNWS Publications, 2007, ISBN 90-5789-113-1 , p. 103.

- ↑ a b Felix 1991, p. 18.

- ↑ Spring 1993, pp. 68-67.

- ↑ Felix 1991, p. 9.

- ↑ Felix 1991, p. 6 and after Westerdijk 1988.

- ↑ Felix 1991, p. 7.

- ↑ Westerdijk 2006, p. 35.

- ↑ Felix 1991, p. 29.

- ↑ Westerdijk 2006, p. 29.

- ↑ a b Felix 1991, p. 15.

- ↑ a b Spring 1993, p. 82.

- ↑ Felix 1991, p. 31.

- ↑ a b c d e Spring 1993, p. 73.

- ↑ a b Spring 1993, pp. 79-82.

- ↑ a b c d Westerdijk 2006, pp. 36–37.

- ↑ Westerdijk 2006, 33–35.

- ↑ Felix 1991, p. 32.

- ↑ Johanna Agthe: Arms from Central Africa , p. 22.

- ↑ Felix 1991, pp. 32-34.

- ↑ Felix 1991, p. 34.

- ↑ a b c Westerdijk 2006, p. 39.

- ↑ a b Spring 1993, p. 78.

- ↑ Felix 1991, p. 35.

- ↑ a b Felix 1991, p. 36.

- ↑ Schurtz 1889 p. 18.

- ↑ Christopher Spring: Swords and hilt weapons , 1989, ISBN 1-56619-249-8 , p. 217.

- ↑ Felix 1991, p. 39.

- ↑ Westerdijk 2006, pp. 39-40.

- ↑ a b Felix 1991, p. 38.

- ↑ Spring 1993, pp. 82-83.

- ↑ Spring 1993, p. 76.

- ↑ Spring 1993, p. 72.

- ^ Paul Germann: African throwing irons and throwing sticks in the Völkerkundemuseum zu Leipzig , 1918/21 (1922), p. 47.

- ↑ Westerdijk 2006, p. 33.

- ↑ Westerdijk 2006, pp. 32–33.

- ↑ a b Spring 1993, p. 71.

- ↑ a b c Spring 1993, p. 69.

- ↑ Felix 1991, p. 43.

- ↑ a b Spring 1993, pp. 71-73.

- ^ Norman Hurst: Ngola: the weapon as authority, identity, and ritual object in Sub-Saharan Africa . Verlag Hurst Gallery, 1997 ISBN 0-9628074-6-X , p. 14.

- ↑ Spring 1993, p. 27.

- ↑ Manfred A. Zirngibl, Alexander Kubetz: panga na visu . Handguns, forged cult objects and shields from Africa. HePeLo-Verlag, Riedlhütte 2009, ISBN 978-3-9811254-2-9 ., Figure 133, p. 282.

- ↑ Felix 1991, p. 67.

- ↑ a b Spring 1993, p. 74.

- ↑ Spring 1993, pp. 74-76.

- ↑ Zungan dowi. Pitt Rivers Museum

- ↑ Rex S. O'Fahey: The Darfur Sultanate: A History . Columbia University Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0-231-70038-2 , p. 93, books.google.de

- ↑ Spring 1993, pp. 76-78.

- ↑ Felix 1991, p. 89.

- ↑ Spring 1993, pp. 78-79.

- ↑ Felix 1991, p. 175.

- ↑ Westerdijk 2006, pp. 80–81.

- ↑ Felix 1991, pp. 93, 97, 109.

- ↑ Westerdijk 1988, p. 244.

- ↑ Spring 1993, pp. 77-78.

- ↑ Felix 1991, pp. 123, 133, 169.

- ↑ Westerdijk 2006, pp. 46, 108.

- ↑ Manfred A. Zirngibl, Alexander Kubetz: panga na visu . Handguns, forged cult objects and shields from Africa. HePeLo-Verlag, Riedlhütte 2009, ISBN 978-3-9811254-2-9 ., Figures 187, 188, pp. 91, 287.

- ↑ Felix 1991, p. 187.

- ↑ Manfred A. Zirngibl, Alexander Kubetz: panga na visu . Handguns, forged cult objects and shields from Africa. HePeLo-Verlag, Riedlhütte 2009, ISBN 978-3-9811254-2-9 , p. 288.

- ↑ musele der Fang / Kota. Higgins Armory Museum

- ↑ The Realm of the Dark Blade: Flying African Blades Of DOOM!