Akrotiri (Santorini)

Akrotiri ( Greek Ακρωτήρι , neuter singular ) is an archaeological excavation site in the south of the Greek island of Santorin (Greek also Thira , ancient Greek Thēra ). In 1967, the archaeologist Spyridon Marinatos discovered a city of the Cycladic culture with a strong influence of the Minoan culture . The city was buried in its heyday by a volcanic eruption and thus preserved for over 3500 years until it was exposed in the 20th and 21st centuries. The excellent state of preservation of the buildings and outstanding frescoes allow an insight into the social , economic and cultural history of the Bronze Age in the Aegean .

The excavation site is named after the present-day village of Akrotiri. It is located about 700 meters northwest of the excavation on a hill with the oldest volcanic rock on the island and is characterized by the ruins of a castle from the time of the Venetian rule (1204–1537).

History of the excavations

In 1867, a French construction company mined pumice stone and Santorin soil on Santorini for the construction of the Suez Canal . Ferdinand Fouqué , the company's geologist, found and registered prehistoric wall remains and shards in a valley below Akrotiri and on the small neighboring island of Thirasia . For the first time he put forward the thesis of a pre-Greek culture buried by the volcano. In 1870 the French archaeologists Henri Mamet and Henri Gorceix found building remains with wall painting fragments in and near Balos (Μπάλος) northeast of Akrotiri, including a depiction of a lily, several storage vessels and a copper saw. Fouqué dated the unearthed vessels to the 2nd millennium BC. Chr.

The first archaeological excavations in Akrotiri were carried out in 1899 by the German Robert Zahn , who found a house, remains of fishing nets, a gold necklace and many shards. The latter also included a destroyed storage jar with an inscription that could later be assigned to the linear A font . A chronological classification was not possible at that time due to a lack of knowledge about the Cycladic culture, and from 1900 onwards the discoveries took a back seat to the spectacular discoveries on the island of Crete, about 110 kilometers south .

Spyridon Marinatos

The Greek archaeologist Spyridon Marinatos , born in 1901, analyzed the rock layers from excavations of a villa in Amnissos near Knossos on Crete in 1939 . He was the first to propose the thesis that the pumice stone found could have come from an eruption of the volcano on Santorini and that the Minoan culture on Crete was wiped out by tidal waves as a result of this eruption. He saw in this catastrophe the core of the legend of Atlantis . Marinatos' conclusions were initially received with skepticism in the professional world.

Almost 30 years later, after the Second World War and the Greek Civil War , Marinatos, who had meanwhile become Professor of Archeology at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens , had the opportunity to search for evidence of his thesis with a planned excavation. As early as 1966, James Watt Mavor Jr. from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution was looking for traces of Bronze Age settlement in various places on Santorini, but with little success. Since he had shared Marinatos' view since 1950 that the Minoan culture that had sunk on Thera could be the legendary Atlantis, he contacted Marinatos. Both met in 1967 on Santorini and Marinatos took over responsibility for all excavations on the island.

By chance, Marinatos learned from a local bricklayer that a few years earlier a donkey cave had broken in near Akrotiri in the southwest of the island, like a field very close by, whereby deeper rooms were accessible. Mavor and Marinatos went to the site of the donkey cave and learned that there were large stone mortars that the locals used as troughs. The place corresponded to the requirements handed down by ancient authors like Strabo and Pindar for a settlement on a flat coastal plain and was on the south coast of Santorini closest to the presumed cultural centers on Crete. Favorable for an excavation it turned out that the pumice stone layer was quite thin here with a maximum of 15 meters due to erosion. On May 25, 1967, the groundbreaking ceremony took place at today's excavation site with the construction of a search trench at the donkey cave.

Bronze Age vessels have already been found at a depth of four meters. On the second day of the excavation, a store room was found, part of a two-story building that is now known as Sector Alpha. The first excavation campaign produced spectacular results overall. Marinatos and his team found a city from the Bronze Age that was close to the Minoan culture based on Cretan models, but had its own characteristics. A volcanic eruption tore the city from life in one fell swoop and was preserved by the layers of pumice stone and volcanic ash as well as only Pompeii and Herculaneum in Italy.

On October 1, 1974, Marinatos was killed in an accident in the excavation area. He fell backwards from a wall from which he was inspecting the excavation work, and hit his head on a stone in "Telchinenstrasse". A little later he succumbed to his injuries. Marinatos was buried at the scene of the accident, where a memorial stone commemorates him. The excavations at Akrotiri were only briefly interrupted because of his death and are still being carried out today, under the direction of Marinatos' assistant at the time, Christos Doumas , who a few years later became professor of archeology at the University of Athens. The success of the excavations at Akrotiri was not diminished by the unfortunate death of Spyridon Marinatos; his original thesis of the destruction of the Minoan culture on Crete by the volcanic eruption of Santorini, however, did not stand in view of the results of later excavations at Knossos.

The dig today

After forty years of continuous excavation, only two hectares of the much larger urban area have been exposed. It is largely a snapshot of the city at the time of its sinking in the middle of the second millennium BC, although its date is controversial. Earlier stratigraphic layers have only been explored selectively, in shafts to accommodate girders of the roof structures. In this ceramic shards and other artifacts from the Neolithic period through early periods of the Bronze Age as of Kastri culture to mittelkykladischen time found.

A circular path through the secured parts of the city allows a tour while work continues on the edge of the site. Shortly after the discovery, the site was covered with a corrugated iron roof on steel girders to protect the exposed buildings and other finds from the weather and intense sunlight. In the years 2002 to 2005, the roof, which was expanded many times over, was replaced by a new construction with funding from the European Union . In September 2005, there was an accident in which part of the new roof collapsed just before completion, killing a tourist and injuring six people. As there were doubts about the stability of the roof, the excavation site was closed. During the interruption of the excavation, the archaeologists concentrated on the evaluation of the existing finds, especially from the deeper shafts. They gained new knowledge about the prehistory of the city. Between 2009 and 2011 a new roof was built in accordance with modern environmental standards, and archaeological research was resumed in the course of 2011. Since April 2012 the excavation site has been open to visitors again. In 2015, Kaspersky Lab signed a long-term funding agreement with the Greek Antiquities Authority and has since supported the restoration of wall paintings and the expansion of the excavations. The research is also funded to a lesser extent by the daily newspaper Kathimerini .

The excavations had a significant impact on the residents of the village of Akrotiri. Before 1967 they were almost completely self-sufficient and isolated from the rest of the island. Around 90% of the population were illiterate. The excavators around Marinatos hired almost the entire male population as helpers, for many this was their first paid job and they had money available for the first time in their lives. With the first reports about the discovery of the city came tourists who rented a room in the village and who were mainly interested in history and academia. The residents of Akrotiri built up a tourist infrastructure and their children, through contact with visitors, often looked for a higher education than average.

The Bronze Age Akrotiri

The excavated part of the city is located on a slope about 200 m from today's coastline. The first traces of settlement go back to the Neolithic Age in the 5th millennium BC. The finds suggest that settlement began as a coastal village on a small, flat peninsula. The oldest ceramics are closely related to types from the islands of Naxos and the Saliagos settlement near Andiparos , but there are also similarities in decor with types from the Dodecanese and especially Rhodes . Ceramic sherds from the early and middle Cycladic times were also found in the same area ( for a chronological classification see: Cycladic culture ).

Settlement was expanded in the early Cycladic period from around 3000 BC. Adopted. The population of the village grew significantly during this time, as can be seen from the construction of a cemetery that stretched up the slope above the peninsula. It consisted of chambers driven into the relatively soft, volcanic rock, which is unusual for the Cycladic Bronze Age. Stone box graves would be typical, but their construction on Santorini was not possible due to the lack of suitable stone for stone slabs. The cemetery was abandoned towards the end of the Early Cycladic II era, and the most recent ceramic styles in the graves belong to the Kastri culture .

Metal processing can be seen from around 2500 BC. BC (period II of the early Cycladic period). Comparisons of styles suggest that the handling of the new material and new ceramic techniques came to the island from the north-east Aegean. There, especially in Poliochni and the surrounding area, in the late 3rd millennium BC Chr. Settlements abandoned for unknown reasons. During the same period, the scope of metalworking in Akrotiri increased strongly, so that it can be assumed that migrants from the abandoned towns brought new skills with them. The city flourished in the Middle Cycladic period after 2000 BC. At that time, the chambers of the Early Bronze Age cemetery were filled with stones and fragments from demolished walls to create a stable base for the expansion of the settlement up the slope. The triggering factor is the discovery of huge copper deposits in Cyprus and the ideal location of Santorini on the trade route between Cyprus and Crete. The settlement now assumed an urban character, the houses became multi-storey and there was the first public infrastructure with a sewer system. New ceramic styles emerged, they became two-tone and featured detailed painting with geometric motifs, but also depictions of plants and animals. The finds from the Middle Cycladic period consist on the one hand of foundations that were found in the shafts. In addition, wall fragments and shards of Middle Cycladic ceramics were used as building material for the late Cycladic settlement and were found embedded in road gravel and masonry. Apart from the shafts, the excavation shows the state of Akrotiris in late Cycladic I, the exact date of which is disputed.

The town

The parts excavated so far do not yet allow an assessment of the size of the city and its population. What is certain is that there is much more to it than just village structures. Insofar as the scientists involved in the project publish estimates at all, the population can be extrapolated to 1,500 to 2,000 inhabitants with conservative assumptions, and up to around 9,000 inhabitants with generous assumptions.

Several decades - according to current knowledge about 50 years - before the final destruction, an earthquake had already severely damaged the city. The residents rebuilt them, mostly using the foundations of the old houses. Some of the rubble from collapsed buildings was not removed from the city, but was used to raise the level of the streets. Preserved buildings were given an extension with a new entrance and staircase, and the former ground floor became the basement .

The streets were paved with large stone slabs, under which the sewer system ran through the whole city in a ditch with a constant gradient. Where the streets were raised after the earlier earthquake, the slabs and sewer system were covered and the new surface was rebuilt with smaller stones, similar to cobblestones. Differences in level of the subsoil were overcome by ramps and stairs, and retaining walls intercepted buildings, squares and streets of different terrain heights.

The only road that has so far been exposed over a longer length climbs up the slight slope from the south with the terrain in a northerly direction. The excavators around Marinatos called it “Telchinenstrasse” because of a metal workshop in one of the houses, after the metalworking Telchinen in Greek mythology. The street runs several times at the corners of the house. With a continuous width between 2 m and 2.20 m, it expands several times to create spaces of different sizes. Workshops in the adjacent houses suggest that craftsmen worked in these places in the open air when the weather was good. The squares were the only open spaces in the city; there are no private courtyards or gardens.

The houses were two- or three-story and built of uncut tuff stones , which were mortared with clay, and mud mixed with straw . Wooden beams supported the ceiling, lintels and lintels. Only traces of them have survived, which is why they were initially replaced by steel beams when the buildings were secured, and later replaced by concrete beams. Hewn stones were used as corner stones, to design the facades of some buildings and to build stairs and other elements. Some walls were reinforced with wooden frames, presumably to protect against earthquakes. The houses with facades made of carved stone were referred to by Spyridon Marinatos as Xesti ( Greek Ξεστ) from ξεω (xeo) for smooth, cut).

The houses found so far can essentially be assigned to two types according to their assumed function:

- The majority of the buildings had workshops, utility rooms and storage rooms on the ground floor or in the basement, on one or two upper floors there was an artistically decorated room, which is interpreted as a semi-private area, as well as other private rooms, some of which were also decorated. This type of house could be free-standing or attached to neighboring houses; As far as buildings were built next to one another, the walls were not divided, but double walls were erected.

- The atypical buildings, sometimes referred to as mansions , had a splendidly decorated area on the ground floor next to utility rooms, which is interpreted as a place for public ceremonies. All houses of this type found so far are free-standing. The house Xesti 3 is considered to be the place of initiation and passage rites, for the building Xesti 4 an administrative function is assumed.

Every building excavated so far had its entrance near the corner of a house; There was always a small window next to the entrance door that illuminated the inner entrance area and through which visitors could be seen. The main stairwell was behind the door. Large rooms had a central pillar made from a wooden beam on a stone foundation.

The wall thicknesses on the upper floors were thinner, the walls often consisted of half-timbered constructions according to the Minoan model, the compartments of which were filled with clay construction or consisted only of rows of windows. As far as these wooden frames were used for interior walls, they were occasionally filled in the lower half through built-in cupboards or consisted of a series of ceiling-high double-leaf doors between wooden pillars, the so-called polythyra . These were used to connect two rooms when all doors were open, or to open only one door and create a passage. When all the doors were closed, the rooms could be separated. Another Minoan architectural element in Akrotiri is the light shaft that was previously found in a building.

Differences in terrain within the buildings were dealt with by means of steps in the floor of the basement, the floor of the first floor was at the same level in all the houses excavated so far. Workshops, shops and storage rooms are mostly located in the basement, which consisted of a series of rooms. Near the stairwell, almost every typical building had a suite of work rooms where food was prepared. Millstones, water containers and so-called pithoi , large clay containers with supplies set into the ground or benches, were found here . Stoves and other fireplaces are rare, which leads to speculation about communal catering in public buildings. Some of these rooms had large windows facing the street; they are interpreted as shops that sell through the windows.

The floors in the simple rooms were made of tamped clay. In the ceremonial rooms, the floors were covered with slates or decorated with simple mosaics made of stones and shells. All the walls were plastered, workshops and storage rooms mostly with clay, living rooms with lime, which was sometimes tinted in earth colors from pink to beige. There are only traces of the roofs; They were probably flat roofs made of twigs or reeds, covered with tamped earth and embedded pebbles in order to achieve thermal insulation against the sun in summer and cold in winter. As in various Mediterranean cultures today, the flat roofs were used as additional living space. They were probably surrounded by parapets about waist height through which stone-carved gargoyles were passed in one or more places.

The buildings indicate a high level of civilization. The houses had bathrooms on the upper floor, which were connected to the sewer system by clay drainpipes. The pipes started on the upper floor on an outside wall, were led through the wall on the ground floor and ended in a pit connected to the sewer system in front of the house under the street.

There are no stables in the city, not even small animals have been kept in the houses that have been excavated so far. It is noticeable that so far no palace or mansion, no city fortifications or other military facilities have been found.

The residents

The city was shaped by seafaring and trade. The people had goods from Crete, mainland Greece and Asia Minor . They operated various trades: the houses that had been excavated so far had metal factories, a pottery, a grape press and two mills. So far there are no finds that clearly indicate shipbuilding. However, it is considered certain that the city had its own shipyards and the related professions at the previously unexcavated port. The high quality of the wall paintings suggests specialized artists. There was a simple loom in almost every house , as shown by the large numbers of loom weights found . Countless shells of purple snails and the high esteem for the saffron crocus show that the clothes made of wool and linen were lavishly colored. There was a variety of agriculture in the surrounding area.

Onions, beans, lentils and chickpeas, flat peas, wheat and barley were on the menu. Figs and grapes were popular as fruit, and pistachios were also known. Sheep and goat meat were mainly eaten, but pigs and cattle were also kept. Fish played a major role in the kitchen, and mussels and sea snails were also eaten. Oil was made from olives and sesame seeds. A beehive made of clay is evidence of beekeeping. Then as now, wine was pressed on the island.

Clay pots have been found in a variety of shapes and qualities. The shapes and décor of the vessels at the beginning of the late Cycladic period were in exchange with the other Cycladic islands, especially Melos as the center of the pottery with a wide variety of styles. Influences on the ceramics in Akrotiri also come from the Minoan Crete and the Mycenaean mainland. The foreign traditions were taken up in the local production, imitated and carried on to individual styles.

Crude tools such as hammers and mortars were made of stone, as were water vessels and fire bowls. Finer tools such as fish hooks, knives, chisels, sickles and the bowls of a scale were made from bronze. Lead was used as a material for weights. Furniture made of wood was found as a negative form in the ashes and could be reconstructed by pouring plaster. The frames found in this way are considered to be the “oldest beds in Europe”. They consisted of a wooden frame on legs, which was strung with cords and covered with a piece of fur or leather.

Wickerwork in the form of baskets and mats played an essential role. The impressions preserved are large baskets in which grapes were transported for pressing, as well as a number of medium-sized baskets in which lime was found, the exact purpose of which is still unknown.

It is not known exactly how the city's residents got their water. There were no cisterns , rainwater was poured into the streets and sewers. A fresco shows a low structure with two jugs and women carrying identical jugs on their heads. In addition, a short section of clay pipe was found, the stability and diameter of which indicate the pipeline of a spring socket. This suggests one or more structurally encompassed springs in the immediate vicinity of the city.

Culture and religion

The function of the painted rooms, of which every house had at least one, is not known in detail. It was noticeably frequent that objects related to the preparation of food were found in the frescoed rooms. In addition, some rhyta , animal-shaped drinking or donation vessels, as well as sacrificial stones and artfully decorated bowls were found in various houses in the city and mainly in painted rooms . Their use for cultural or cultic purposes is to be assumed, but details are not discernible.

|

|

|

|

Golden goat idol and its location in the clay box ( larnax ) on the left of the right picture; on the right the pile with animal horns

|

||

In the south-western part of the excavation, the best finds so far with a religious or liturgical reference were made. During the excavations for the foundation of a support post for the roof inside the “House of Banks”, in 1999, covered with pumice stone, heaped horns mostly from goats and cattle and a single pair of deer antlers were discovered. Immediately west thereof was a small earthen box, as Larnax referred to in the pumice, of a goat Idol contained gold. The figure is 11 centimeters long, 9 centimeters high and weighs 180 grams. The body and head are cast using the lost wax technique, the legs, neck and the rectangular base were later added with bronze solder . The goat idol originally stood in a red wooden box, the imprints of which and remains of paint have been preserved on the inner wall of the Larnax.

In the adjacent building Xesti 3 to the north-east there was a depression that was originally interpreted as a lustration basin for initiation rites, but after closer examination is more likely to be associated with an adyton . So far, comparable institutions are only known from Crete. The Xesti 3 building with the basin is lavishly decorated with frescoes, including the fresco of the saffron collectors. A shrine has been preserved on the east wall, which was decorated with "cult horns", as Arthur Evans called the stylized bull horns, which had a previously unknown religious meaning in the Minoan culture.

The function of the facilities on the largest site of the excavation to date is unclear. As early as 1969/1970 Marinatos found the first rock chambers under what he later called the cenotaph square, which are now recognized as the graves of the early Cycladic settlement. The chambers under the square are partly flat and open at the top, partly they are more than a meter deep, have a vault carved out of the rock as a ceiling and were accessible through a covered corridor. During the city's heyday, they were filled with earth and rubble in which countless fragments of ceramics were stored.

Above the chambers, on the south side of the square in front of the Delta building complex and west of the Xesti 5 building , there were several facilities that presumably served cultic purposes. Marinatos dug up what he called the sacrificial fire : It consisted of a recess in which ashes and bones of animals, goat horns and four clay figures of cattle were found. There were also various ceramic vessels and a large amphora that contained beans . This sacrificial fire was connected to a shallow stone enclosure in the west, in which further finds were made, including a pithos about 1.30 m high, which was carved in a piece of volcanic rock, and a small, portable stove or oven from the same Material.

A structure of large, flat stones, several boulders and smaller stones was found further east on the square, piled up to form a hill with a largely flat surface. It was initially interpreted as a cenotaph and gave the place its name. At the edge of this stone mound a stone bowl was discovered with small round pebbles in it. Inside the hill there was a deposit of Cycladic idols . Ceramic vessels in the structures allowed them and the backfilling of the rock chambers to go to phase III of the early Cycladic period and around 2200 to 2000 BC. BC, so were around 500 to 600 years older than the city when it was destroyed. The keeping of these objects, which were already ancient at that time, in an important square in the city is explained with cultic purposes. As a motivation, Doumas cites that the underground chambers, because of their funeral function, were viewed as spiritual dangers that should be averted by the cult objects and facilities. The pebbles, which were ground in the sea, because water is associated with purification and salvation in traditional religions, go well with this.

So far, no necropolis has been discovered that can be attributed to the city in its heyday. In the grave chambers frühkykladischer no burials have been found in adults, but in one of the chambers were several ceramic vessels in which ash and bony remains of by cremation interred children were found. South of today's island capital Fira , the remains of a burial site from presumably early Cycladic times were discovered in a quarry in 1897 and a few years later, Hiller von Gärtringens' employees found individual graves around three kilometers north of Akrotiri (near today's Megalochori), which they were unspecific to the era before Associated with eruption. Their knowledge of the chronological classification of the Cycladic cultures was still very little and their records are so imprecise that details of the graves and the exact location are unknown.

Economy and social structure

In the 1990s, discoveries were made that give an insight into the city's trade relations. In one of the mansions , fragments of clay tablets bearing inventory data in linear A were excavated . From these entries it appears that Akrotiri traded in large quantities of sheep wool and olive oil. Since the island was rather unsuitable for cattle breeding due to its surface texture then as it is today, the many weaving weights and remains of textile dyeing that have been found suggest that Akrotiri was a center of the processing industry for textile products in the Middle Bronze Age . Wool and probably also flax were bought, spun and woven into cloth, dyed and traded from the northern neighboring islands, probably especially in the cultural center of Crete. This form of division of labor is rare in premonetary societies.

Olives were grown on the Aegean islands in greater quantities than today; here Akrotiri played an essential role in trade. In period I of the late Cycladic period, almost 50% of all swing jugs found in the area of the Cycladic cultures, Crete and Cyprus - the typical trade unit for both olive oil and wine - come from Santorini. The ideal location on the main trade routes has been a key factor in the island's economy. In particular, Santorini was the only island that could be reached within a day trip from Crete. Since the trading ships of the Bronze Age did not sail at night, but had to seek shelter in bays, the island was the central stepping stone for the trade of the Cretan Minoans with all markets in the north.

Agriculture on the island itself started from scattered small farms, three of which have so far been found. Two of them consisted of stone buildings with only one room, the third two rooms, a walled courtyard and a storage room or stable. The further settlement of the island has been little explored because of the lava cover. Apart from the farms, individual wall remains in connection with ceramic shards from the Akrotiri era were found in various places. Their extent, context and use are not known.

A collection of seal impressions found in the 1990s cannot yet be put into context. There are several dozen clay discs with imprints depicting around 15 different subjects. Possibly they were trademarks, they were found in a kind of collection, not attached to different goods.

Conclusions about a balanced social structure, at least the so far excavated part of the city, can be drawn from the frescoes. Every house has at least one painted room. In some houses, the motifs of the frescoes indicate the occupations or origins of the residents. The resident of the west house with maritime motifs was possibly a captain or a merchant. It is possible that the inhabitants of the so far uncovered quarter belong to an elite , because it is known from Crete that at the beginning of the late Minoan period there was no egalitarian society, but rather that elites operated a complex gift economy with each other around the exchange of favors and goods and through oppression struggled for their position in society . It is also fitting that analyzes of the architecture and the arrangement of some frescoes in the buildings allow the conclusion that wall paintings were also attached for their effect on the outside. They could be seen through windows from outside the building and, in addition to their ritual use, could at least in some cases also have served to compete for social status .

If no fortification of the city and no other military facilities are found, the connections to the dominant culture on Crete must be assumed to be much closer than previously assumed. Akrotiri was then not in competition or even opposition and therefore had no coercive measures to fear, as the fortifications of other simultaneous settlements on the northern neighboring islands, for example Phylakopi on Milos , suggest. As an explanation for the close relationship and the cultural connections, it is assumed that Cretans came to Akrotiri as merchants, craftsmen or artists, married into leading families on the island and thus formed a family-related, mixed elite.

Analyzes of the ceramic finds from the end of the Middle Cycladic period and the transition to the late Cycladic epoch show that imports from Crete do not account for more than 10%, later 15% of the finds, but gradually had a clear influence on the development of local decorations and styles in Akrotiri. From the slow course it is concluded that the city was not a colony, otherwise the influence would suddenly have increased, but a slow cultural process took place in which Akrotiri approached the Minoan culture, but developed independent features. Akrotiri thus differed from other places in the southern Aegean such as Miletus , where Minoan ceramic styles were adopted early and quickly, or the island of Kythira , which can be regarded as completely Minoan assimilated at the end of the pre-palace period . In the akrotiri of the late Cycladic culture, Minoan units of measurement were also used; the weights found in the city were identical to those from Crete in terms of their mass and denomination.

The downfall

Unlike in Pompeii, no human remains have been found in the layers of ash and pumice stone at Akrotiri. There is no jewelry in the houses and only a few elaborately made tools. This suggests that the residents had time before the volcanic eruption to gather their valuables and flee onto the boats.

The warning of the actual eruption apparently came from an earthquake. His traces can be seen on the steps of carved stone, all of which are broken in the middle, as well as in damaged walls of the buildings. After the earthquake, some of the refugees returned. They cleared the streets, tore down damaged walls and sorted out reusable building materials. They also hid furniture and goods. A stack of bed frames was found that had been prepared for removal from a house. Undamaged jugs and amphorae of food had also been taken to collection points outside the homes.

This removal did not take place before the volcano wiped out the settlement. According to current knowledge , the eruption, the so-called Minoan eruption , began with the ejection of light pyroclastics from a volcanic vent that was almost exactly in the middle of the island. The eruption lasted only a short time and the amount of loose material expelled was small, so that the rescue teams were able to get to safety. However, there is no evidence on any of the neighboring islands that major immigration took place around the time of the volcanic eruption. It can therefore be assumed that the refugees died after all due to gases from the eruption or tidal waves.

The actual outbreak came months later. Grass was already growing on some stumps of the wall, the burnt remains of which have been found. The eruption consisted of several phases. The first was the discharge of relatively light pumice stone, which was deposited in a comparatively thin layer no more than seven meters thick. It caused roofs to collapse due to overload, but protected the buildings from being destroyed by the later, heavier phases. These brought thick layers of ash and lava chunks of up to 5 m in diameter, in other parts of the island even up to 20 m.

After the end of the eruption, prolonged intense rainfall fell on the remains of the island. They gathered in torrents and washed deep gullies into the devastated landscape. One of the drainage channels runs through today's excavation and it filled several rooms so quickly and so completely with the mud and ash that it was that objects have been preserved here particularly well.

The dating of the Minoan eruption and thus the fall of the city of Akrotiri is not completely certain. The city's most recent ceramic styles belong to the Late Cycladic IA phase. They are synchronized with the Egyptian chronology via finds in Crete and Egypt and thus to approx. 1530 BC. Dated. Scientific methods of classifying the eruption using the radiocarbon method and the deposits of volcanic ash in the Greenland ice point to the 1620s BC. Chr. The interpretation of the contradicting information and its possible consequences for the dating of all cultures dependent on the Egyptian chronology is the subject of a debate in the specialist sciences ( see Minoan eruption ).

Judging from the sparse archaeological finds, it took several centuries for the vegetation to recover enough that the island became attractive for human repopulation. Individual sherds from the SH IIIB phase of the Mycenaean culture around 1200 BC Were found at Monolithos. Herodotus reports of a Phoenician settlement, which, however, has not yet been proven. A notable population came only in the 9th century BC. BC with the Dorians , after whose leader Theras, handed down by Herodotus and Pausanias, the island was named "Thera" from then on. They no longer settled on the site of Akrotiri, but built their city of Alt-Thera on a ridge of Mount Messavouno, above the present-day town of Kamari .

The frescoes

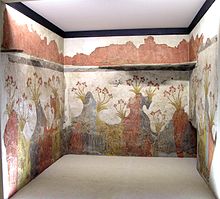

The diverse frescoes are indicative of the high standard of living of the Akrotirians. The topics range from geometric patterns to everyday scenes, seafaring and agriculture to sporting or cult games. Landscape images show the flora and fauna on Santorini and those of exotic countries such as Egypt . The use of colors for decorative purposes has been found in Crete since the Neolithic, the handling of purified pigments and abstract motifs begin with the Old Palace period . Figurative representations can be traced back to the time of the New Palace on Crete.

The frescoes of Akrotiri are more strongly influenced by the Minoan culture than on other islands in the Cyclades, but they in turn influenced the imagery of the region. A miniature frieze was found in Ayia Irini , on the island of Keos , which is reminiscent of the friezes of the west house in Akrotiri. Another frieze of this type was found in Tel Kabri ( Palestine ); geometric motifs with great resemblance to Akrotiri are known from the palace in Qatna , Syria .

execution

The wall paintings were typically started on damp plaster, but, unlike the classic frescoes, continued on the dried surface in the sense of a secco painting, so that the durability is different in different parts of the picture.

The frescoes in the houses differ significantly in theme and style, as different artists were at work. What they have in common is the meticulous and detailed execution and the color spectrum used. In addition to the white of the limed subsurface, three main colors were used: yellow in the form of ocher and occasionally jarosite , deep red also from ocher and occasionally hematite and a strong blue from Egyptian blue and occasionally the silicate glaucophane , or, according to more recent analyzes, riebeckite . The blue lapis lazuli has been found once in Bronze Age Greece, but not in Akrotiri. Graphite and mixtures of very dark blue and black were used to draw contours and details. The colors were usually used in pure tint. Mixtures and shades are only used sparingly in a few paintings. Green from malachite only appears in traces, especially not where one would expect it: in pictures of plants.

Colors play an essential role in the stylization of representational motifs. They are often not used in accordance with the realistic appearance, but to structure the image through adjacent colored areas.

Motifs

In addition to decorative patterns and frames, the frescoes mainly show scenes and motifs from people's lives. They allow a detailed insight into the culture and society of the Bronze Age.

people

Images of people offer a special approach to the life of the Bronze Age acrotirs. Some men who are shown performing formal, possibly ritual acts, wear a long coat in white, which is unusual for the Aegean cultures, as described in Linear B texts from Knossos, Crete and several centuries later in Homer as Chlaina (χλαινα ) is mentioned in one or two forms. It was either decorated with two vertical stripes on the front or the depiction refers to a double-layered way of wearing.

A few figures of both sexes who are interpreted as conductors of ceremonies wear a robe known from the Middle East. It is a cloth that is wrapped twice around the body, once under the armpits, the second layer over the shoulder, where it is held with a clip and from where the rest of the cloth falls loosely over the back. Here, too, the robes are decorated with two broad stripes. Nobody else wears a white robe with decorative elements. Some townspeople are also dressed in white, but without any special additional signs.

Apart from the priestesses mentioned, women wear either an ankle-length colored skirt and a blouse with sleeves up to the elbows or a dress with short sleeves, the top of which is closed at the front well below the breasts. The dresses are made of a woven fabric and are often striped.

Apart from individual representations and smaller groups, which appear on the frescoes in almost all buildings, the crowd scenes in the Westhaus are most expressive. About 370 people are depicted on the miniature frescoes in the ceremony room. Of these, 120 are only schematically represented rowers in the boats, others are too poorly preserved for an assessment. There are around 170 male figures with sufficiently recognizable clothing facing only ten women. While most men are portrayed individually, almost all women appear uniformly in clothes and hairstyle only on the city windows. The few exceptions are the priestesses listed above.

Most of the city dwellers are dressed in a kind of cape that comes in white, red and ocher and blue and black. Underwear is not visible. In a corresponding illustration, shepherds and goat herders wear the same clothes in a heavier form with a similar cut. A number of people wear various shapes of loincloths or skirts. Some only wear a belt that holds a strip of cloth through the crotch, the ends of which hang short at the front and longer at the back. These are mainly people who are shown doing physical work, such as fishermen, rowers or shepherds.

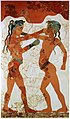

Nudity occurs in two contexts, the dying in a shipwreck scene are depicted naked to express their vulnerability, and some almost life-size images, which are particularly used as room decorations, show nudity.

Warriors carry swords, spears, shields and a helmet. Swords of bronze were rare, expensive and ineffective. They were worn as stabbing weapons, but rarely used in combat. The main weapon was the spear , which was also used in hunting. The length of the spears in the frescoes is grotesquely exaggerated compared to their height. It is more than four meters and if it were real, the weapon could not be held loosely in one hand. Spears of approximate length would be realistic. Two types of shields are known from the Greek Bronze Age, the rectangular shape and shields in the shape of an eight. Images of both types can be found on representations in Mycenae. Only the first type is represented in Akrotiri. This sign was too heavy to be carried in hand, so it was hung on a strap. Helmets were felt caps with leather trimmings. Eminent warriors wore boar-tooth helmets , the leather strips of which were studded with rows of wild boar tusks. Homer describes the same type in the Iliad .

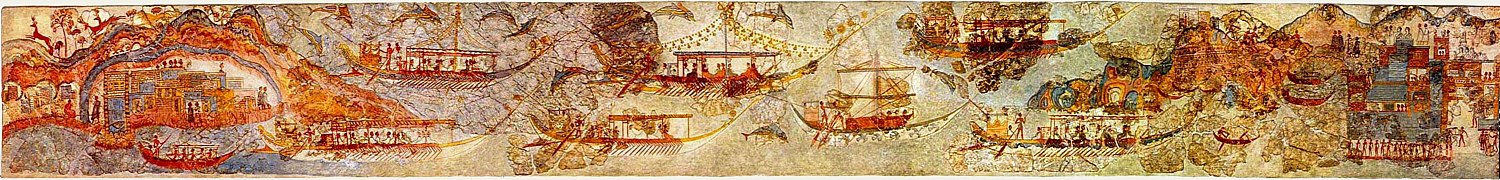

Ships

The way its boats are portrayed is particularly characteristic of a maritime and commercial culture. Most of the boats were driven by oars, and sails could only rarely support the propulsion, as it was only possible to sail before the wind . The larger boats depicted on the frescoes range from five to 24 oars. Due to the perspective, the same number must be assumed on the other side. The boats were seaworthy and could easily reach destinations further away. They had tent cabins on the quarterdeck and partly on the foredeck for passengers and maybe also the officers. The helmsman stood in front of the aft cabin and steered with a rudder on the right-hand side, the name of which is still known today as starboard . The hulls were often adorned with animal symbols, lions, dolphins and birds stand out. The rigging of one of the boats is hung over and over with stylized saffron crocus flowers. Only one of the boats is shown under sails, although the larger ones have mast and rigging. The hull of the sailing boat is adorned with symbolic doves. An attempt at interpretation sees a courier in this boat.

In addition to the large boats with several rowers, there are small paddle boats used by fishermen.

Cities and buildings

A frieze of the west house shows two cities and a sea voyage from one city to another. The cities are shown embedded in a rocky landscape with sparse vegetation. They consist of individual houses that were placed in front of and against each other in a flat perspective. The facades have been painted in great detail. One can distinguish walls made of irregular field stones, plastered facades and a few walls made of regular bricks. The plastered walls are kept in shades of blue and ocher, a single house shines in a bright red. The houses have large windows and flat roofs with a wide overhang that is probably used for weather protection. Some houses in the larger city have roof tops that are reminiscent of the shape of a pine cone. In addition, a conspicuous building in the larger city is adorned with " cult horns ", as they are known from the Minoan culture and isolated Cycladic settlements. It is therefore considered a consecrated shrine.

A sanctuary called temenos (τεμενος) outside the city of the same fresco is also adorned with the cult horns of the unspecified religion . The picture is poorly preserved, so not much can be said about its design. Another fresco in the same room shows a small building with cult horns, which is interpreted as a sacred spring. The structure is shaped by columns, with the large horns probably serving as a symbolic mark of the building's character.

A fresco shows a building that can be interpreted as part of a port facility. Ships could be parked and repaired in several parallel chambers above the coast in the winter storm season.

Landscapes

Scenic representations with landscapes are mainly known from the Westhaus . The following landscapes are shown there:

Coastal landscapes coincide with the coastlines of the Cyclades and Santorini in particular. Even if today's island has been greatly changed and shaped by the great volcanic eruption, the combination of natural rock and volcanic rock corresponds to the appearance of that time.

As in other artistic representations in the Aegean Sea, the sea is not depicted here. Water areas are marked by dolphins, fish, snails, starfish and aquatic plants, but they themselves remain invisible.

Rivers are a rare motif in the Greek Bronze Age. Apart from a representation in Akrotiri, only inlays of a dagger from Mycenae are known. Engravings on a ridge from Pylos (Peloponnese) are also carefully interpreted as a river. All of these rivers run horizontally, in irregular, near-natural oscillations, with characteristic vegetation and fauna on the banks.

Animals

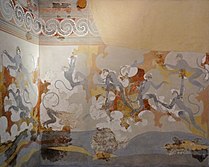

Most of the animals are faithfully reproduced in form and movement. Frequently, however, the colors are not selected according to nature, but rather to the needs of the artist in order to work out body shapes through contrasting colored surfaces. It is noteworthy that some animal species unknown in Santorini have been depicted in detail. The artists therefore had access to the iconographic traditions of Egypt, so North African species such as big cats, antelopes and monkeys as well as mythological animals such as the griffin could be depicted here.

On the already mentioned river, several realistic scenes of predators on the hunt are shown. A bright blue cat creeps low through the vegetation on the banks of the waterfowl. Body shape and pattern of spots are reminiscent of a serval . However, this interpretation is not considered to be certain. It could also be the house cat, domesticated in Egypt in the Bronze Age, or a black cat . So far, no representation of a living lion has been found in Akrotiri , as is known from other sites in the Cyclades and neighboring cultures. Only a stylized lion adorns the hull of a ship as a symbol that can be interpreted as a warship by armed men on board.

Not unusual for the Cycladic cultures is the depiction of a griffin with a lion's body and wings on the hunt for a deer in the lifelike river landscape. Its head has not been preserved, so it remains to be seen whether it was depicted as a falcon, as is common in Egyptian depictions, or as a vulture, which the shape of the neck suggests. Griffins have a long iconographic tradition that began in the 4th millennium BC. Starting from Mesopotamia , spread over Syria and Egypt in the Aegean Sea. The oldest finds in the Cyclades come from Phylakopi on Melos in phase III of the Middle Cycladic period. In Akrotiri two representations on frescoes from the beginning of the late Cycladic period are known. In addition to the river landscape, a strongly stylized griffin appears in the “Saffron Collectors”. There is also a depiction of a griffin on a particularly large pithos from the Middle Cycladic layer and a pottery shard with a beak, head and neck, which is interpreted as that of a griffin, and a seal imprint of a sphinx with a bird's head. The use seems to be largely interchangeable with lion depictions as a symbol of strength and power. There is speculation in literature about a divine role.

A deer serves as the prey of the griffin. Its representation and coloring are true to life, so the artist was familiar with the model.

Cattle are rare subjects in the Cyclades and even rarer in Akrotiri. In one of the large wall paintings, two poorly preserved animals are led by a person in front of a city gate. Seal impressions also show a bull motif . In both cases, they may be sacrificial animals . Finds on Delos show bulls with a double ax as a religious motif of the Minoan culture or tied to a shrine. Sheep and goats are depicted as herd animals in a shepherd scene .

Antelopes are depicted in two large-format and very lifelike frescoes. Monkeys are shown several times. Both animal species were not native to the Aegean Islands. The monkeys may be vervet monkeys , which would indicate contacts with Egypt. The Ethiopian green monkey and the southern green monkey are still widespread on the Upper Nile . However, the monkeys shown could also be Indian langurs that are native to Nepal , Bhutan , northern India and the Indus Valley .

Apparently popular in Akrotiri, but rarely on other Cyclades islands, the motif of the dolphin is . It appears ten times on amphorae from Akrotiri alone, but hardly once on other ceramics. Dolphins also populate scenic representations of the sea and are highly stylized as motifs for decorative wall paintings. All representations of the dolphins are very similar and are schematic. Sometimes dolphins are depicted with trains of fish (dolphin according to outline and coloring, but with gill covers in phylakopi).

Representations of birds are popular. Water birds, especially geese, live in landscape scenes. Egyptian geese are recognizable as a species , other animals can either be gray geese or possibly a free combination of the artist between gray and Egyptian goose. Detailed images of pigeons have not yet been found, only stylized pigeons adorn several ships as symbols. In particular, the hull of the only ship depicted under sails is adorned with a chain of stylized doves. This is interpreted as an indication of a courier function of this ship. Swallows are depicted several times, especially in a flowery landscape that is interpreted as a spring motif. They are often depicted on ceramics, so often that they can almost be used as identification marks for vessels from Santorini.

plants

The flora is depicted in great detail so that it can still be recognized after 3500 years. Of trees are pine , pistachio , olive and fig trees to detect. Some of the figs may also be holm oaks , as the lobed leaves are displayed slightly differently. A large variety of plant species is represented on a watercourse, here sedges , grasses and reeds can be identified.

The papyrus has a special role. It is depicted in landscape paintings on the one hand, but also in large format in individual representations on both frescoes and clay pots. Papyrus is strongly stylized, depicted as an immature plant. The images in Akrotiri are largely identical to those known from Mycenae , Phylakopi (on Melos) and Knossós (Crete), which speaks for a direct exchange between the artists or among them. An alternative interpretation, which goes back to Marinatos, sees the plant as a dune-funnel narcissus , although a special cultural function of this plant species is not yet known.

The date palm , a relatively common motif on Akrotiri, is almost unknown on other Cycladic islands. The figure is biologically very exact in the forms, but not in the coloring; this seems to have been used more because of its contrasting effect. The date palm was occasionally depicted on ceramic vessels. So far, a picture of the dwarf palm has only been found once .

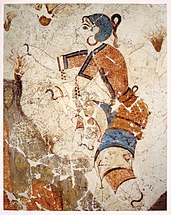

Saffron can be seen as a symbol of Santorini . As a plant and as a decorative element, it is depicted in many ways. The best known is the "Fresco of the saffron collectors" from House Xeste 3, which Marinatos found as the first large mural in 1969 and which was published worldwide. In connection with other frescoes and other finds in the same house it is interpreted as part of a female initiation rite. The stylized saffron plant was often used as a motif on ceramics and frescoes. Several ships depicted in a lake scene are adorned with stylized saffron flowers. Here they are interpreted as a symbol for spring.

Frescoes in the west house

The west house, which has already been mentioned several times, is the most abundant source for scenic representations to date. In just one room there are three friezes that run above a window front and two interior walls partially pierced by doors, as well as two almost life-size depictions of young naked fishermen in fields in diagonally opposite corners of the room. Several other murals with a maritime theme can be found in an adjoining room.

The three friezes show the following representations (the first two mentioned belong to a frieze, any connecting parts between them have not been preserved):

- Ceremonies on the hill - festively dressed people of both sexes move from two sides on a hill, at the foot of which a holy spring rises. Several present unrecognizable objects in their outstretched hands, possibly fire bowls.

- In a stylistically confusing depiction, a shepherd's scene with a herd of sheep and goats forms the background for a number of striding warriors in full combat gear. Next to it, a building is depicted on the coast that can be viewed as a ship warehouse. Directly below the building and the row of warriors, without any discernible connection, a ship has run aground on rocks, three naked people fall overboard into the sea, pulling unidentifiable pieces of equipment with them.

- A further demarcated field is a river landscape. This motif is part of a recognizable Cretan tradition, where Egyptian landscapes are usually taken up after flora and fauna, while the river in Akrotiri is to be regarded as local according to the vegetation. The river provides the framework for two sub-themes: predators hunting and plant cultivation (palms, papyrus).

- The “ ship procession ” is considered the highlight of the previously discovered frescoes in Akrotiri . At least eight ships sail from a smaller town, presumably a short distance, to a larger and more decorated town, where they are expected. The distance is considered short, as the boats are obviously not equipped for sea voyages. There are festively dressed passengers on board, not soldiers, so the journey is aimed at a friendly destination. One interpretation wants to recognize from landscape details that the journey takes place inside the island caldera.

An interpretation in connection with all the pictures in the room interprets the procession as a celebration of the beginning of the seafaring season in spring, after the end of the winter storms. All images would loosely relate to the theme of spring, if the ceremony on the hill was interpreted accordingly.

Frescoes in Xesti 3

The building Xesti 3 in the southwest of the previous excavation is interpreted as a public building for initiation and passage rites. In addition to the neighboring depot of animal horns and antlers with the golden goat idol, the rich furnishings of the building with frescoes of various contents contribute to this. Xesti 3 contains the largest number of frescoes ever found in the city. A room with a depression that was initially interpreted as a lustration basin, today as an Adyton, has a niche interpreted as a shrine, in which a double bull horn made of stone was found. The room is connected by polythyra with a series of other rooms. On the upper floor there are other rooms that are connected with a cultic purpose, they are all lavishly painted.

On the ground floor, three women are depicted above the recess with the shrine. One holds her injured foot, the other two present a chain and a piece of clothing. Next to it, a portal is painted on the wall, which is crowned by cult horns from which blood is running down. In the same room, but in a part that cannot be seen through partitions from the pool, four naked boys and men are shown, two of whom are clearly recognizable as adults and one as a child.

The most prominent fresco from Xesti 3 are the "Saffron Collectors". The long fresco extends over the north and east walls on the upper floor, only parts of it have been preserved. From left to right an iconographically remarkable scene develops in which a woman sits on a throne in front of the landscape. She is guarded by a griffin behind her, wearing a collar and leash, by which the seated ruler or goddess is holding him. A young woman bows to her and pours something, probably saffron , a type of crocus , in front of her. Between the woman and the goddess, a monkey of the goddess depicted in blue tones with the gesture of an offering extends a bowl that presumably contains the crocus. Because of the animals, the representation is referred to as the "mistress of the animals" and identified with the Potnia theron .

In the middle of the wall, in a poorly preserved part of the fresco, a woman is carrying a vessel through a hilly landscape with individual crocus flowers. The hilly landscape continues after the corner of the room on the east wall, here a young and an older woman are picking the saffron crocus blossoms. They are shown in detail and with individual features. The representation of the relationships between the two women is interpreted as a teacher-student relationship. The representation is interpreted as a female initiation rite in which women of several generations take part in different roles. Fragments of two other frescoes are still preserved in the same room. One provides clues for another, fifth woman, the other a reed landscape with water birds.

A mountain landscape with two animal scenes and at least one person was found at the entrance to the building and in the stairwell, decorative patterns have been preserved on the second floor, under which rosettes and spirals stand out. Other landscape motifs and fragments of other representations have not yet been restored.

It is noticeable in the representations that many people are shown, as well as the separation of the sexes. The iconography has not yet been understood in detail; the overall cultic impression is certain. It is believed that ritual acts were performed on both the ground floor and the first floor and that the participants were gender segregated.

Figurative sculptures

Since the discovery of the city of Akrotiri, earlier finds from the island have been more precisely assigned. Two 15 cm marble figures in the style of Cycladic idols have been known since 1838, depicting harpists and belonging to the Spedo type ( further information under Cycladic idol ) of the Keros-Syros culture of the early Cycladic period . They are exhibited in the Badisches Landesmuseum in Karlsruhe . According to the Karlsruhe catalog, a grave find in the early 19th century on the island of Santorini is "credibly described" as its origin. It is probably from a grave from a necropolis . The quality of the work suggests that the deceased had lived in the island's cultural center, which points to Akrotiri.

The finds around the Kenotaph Square, the largest previously excavated square in the city, are remarkable. Seventeen idols lay there, ten of them together with a bronze knife and obsidian tools as a deposit in a niche in the so-called cenotaph . A further twenty idols have so far been found elsewhere in Akrotiris. They confirm the thesis put forward by Jürgen Thimme as early as the 1960s that the abstract idol types are derived from natural stones found on the coast that were abraded by the sea.

Five of the stones are completely unworked, they are flat and have a shape roughly reminiscent of human shoulders with the base of the neck. In the case of nine stones, this type of shoulder was deepened on the forms found by more or less intensive processing. Twelve other figures are assigned to the violin type; they are still abstract, show the features of a female body with bulges constricted by a waist and a neckline. The 26 abstract idols are juxtaposed with 11 figurative ones. Eight is the let Plastirastyp assign one the Spedostyp , another the Chalandrianityp . Most of the abstract figures date from the Neolithic Age in the 4th millennium BC. BC, the canonical figurative idols from the early Cycladic period to around 2500 BC. Chr.

Exhibitions

The excavation site can be visited again since April 2012. The circular route through the city leads from the south along the largest building complex to the main square and back out of the excavation along the longest road that has been exposed to date via two small squares. Insights into the basement and ground floor rooms are possible and visitors can see the architecture of a stairwell and various entrance areas up close. You will see details of the construction of walls such as the arrangement of load-bearing beams and the facade design. In some rooms pithoi , amphorae and other ceramic vessels as well as millstones and other artifacts are arranged similar to the find situation. The roof is largely covered with a thin layer of earth, which moderates the climate under the roof even with several thousand visitors a day. Windows in the shed roof , facing north, are provided with ventilation openings and let light into the excavation site.

A fortunate circumstance during the excavations was that when the first wall paintings were discovered, thanks to the experience with Byzantine frescoes in Greece, sufficient specialists were available for the salvage, restoration and reconstruction. The frescoes have been restored in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens and most are on display there. In 2001 the new archaeological museum opened in Fira, the capital of Santorini, and since then some frescoes from Akrotiri can be seen on the island itself. In the museum there are also many ceramics, clay tiles with linear A lettering, water containers made of tuff and plaster casts from furniture, as well as individual Cycladic idols.

An exhibition of detailed replicas of almost all the frescoes found by the Thera Foundation so far has been on view in the Santozeum Exhibition Center in Fira since 2011 .

The images of ships in Akrotiri, in particular the “ship procession” in the west house , served as templates for the seaworthy reconstruction of a Minoan ship. The Minoa was built between 2001 and 2004 by craftsmen and scientists using traditional methods in Crete and was presented to the public on the occasion of the 2004 Summer Olympics in Athens. It is exhibited in the Maritime Museum at the port in Chania , Crete.

literature

- Christos G. Doumas : Santorin - The prehistoric city of Akrotiri . Short educated archaeological guide. Hannibal, Athens 1980.

- Christos G. Doumas: Thera Santorin - The Pompeii of the ancient Aegean . Translated by Werner Posselt. Koehler & Amelang, Berlin et al. 1991, ISBN 3-7338-0050-8 .

- Christos G. Doumas: The most recent archaeological finds in Akrotiri on Thera . Manuscript of a lecture, Association for the Promotion of the Processing of Hellenic History, Weilheim i. Obb. 2001.

- Christos G. Doumas: The early history of the Aegean Sea in the light of the most recent archaeological finds from Akrotiri, Thera . Society for the Support of Research in Prehistoric Thera, Athens 2008, ISBN 978-960-98269-2-1 .

- Phyllis Young Forsyth: Thera in the Bronze Age . Peter Lang, New York 1997, ISBN 0-8204-3788-3 .

- Nanno Marinatos: Art and Religion in Ancient Thera . For the reconstruction of a Bronze Age society. Mathioulakis, Athens 1987, ISBN 960-7310-26-8 .

- Lyvia Morgan: The Miniature Wall Paintings of Thera . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge et al. 1988, ISBN 0-521-24727-6 , ( Cambridge classical studies ).

- Clairy Palyvou: Akrotiri Thera. An architecture of affluence 3500 years old . INSTAP Academic Press, Philadelphia 2005, ISBN 1-931534-14-4 .

- Rainer Vollkommer : Great moments in archeology (= Beck'sche series . No. 1395 ). CH Beck, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-45935-8 , Santorin and the story of the sunken Atlantis.

Web links

- Website of the Greek Ministry of Culture about the excavations in Akrotiri (English)

- Website of the New Archaeological Museum in Thera (English)

- Website of the Thera Foundation ( Memento from September 5, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) with various articles on the island of Santorini with a focus on the history and art of Akrotiri from the Bronze Age (English)

- Idryma Theras-Petros M. Nomikos: Exhibition of the reproductions of the wall paintings of Thera (English)

- Michael Siebert: Cult and Divinity in the Wall Paintings of Akrotiri (2014)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Vollkommer 2000, p. 87.

- ↑ a b c Vollkommer 2000, pp. 88/89.

- ↑ This chapter follows the presentation in Palyvou 2005.

- ↑ Vollkommer 2000, p. 90.

- ↑ Vollkommer 2000, p. 96.

- ↑ Colin Renfrew et al.: The Early Cycladic Settlement at Dhaskalio, Keros - Preliminary Report of the 2008 Excavation Season. In: The Annual of the British School at Athens . Volume 104, 2009, p. 35.

- ^ AFP , Greek excavation site closed after a fatal accident , September 24, 2005.

- ↑ Athens News: Akrotiri reburied ( Memento of August 22, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) , July 25, 2008

- ↑ a b c d e Christos Doumas: Akrotiri, Thera - Some Additional Notes on its Plan and Architecture. In: Philip P. Betancourt, Michael C. Nelson et al. (Eds.): Krinoi kai Limenes - Studies in Honor of Joseph and Maria Shaw. INSTAP Akademic Press, Philadelphia 2007, ISBN 978-1-931534-22-2 , pp. 85-92.

- ↑ a b Christos G. Doumas: Managing the Archaeological Heritage: The Case of Akrotiri, Thera (Santorini). In: Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites. Volume 15, No. 1 (2013), pp. 109-120, 117.

- ↑ a b Athens News: Akrotiri archaeological site opens its doors once more ( Memento of July 1, 2012 in the Internet Archive ), April 11, 2012

- ↑ ekathimerini.com: Akrotiri excavations on Santorini start up again with funding injection from Eugene Kaspersky , July 1, 2016

- ↑ Panayiota Sotirakopulou: Late Neolithic Pottery from Akrotiri on Thera - Its Relations and the Consequent Implications. In: Eva Alram-Stern (ed.): The Aegean Early Period - Volume 1, The Neolithic in Greece . Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1996, ISBN 3-7001-2280-2 , pp. 581–607.

- ↑ a b c Christos Doumas: Akrotiri. In: Eric H. Cline (Ed.): The Oxford handbook of the Bronze age Aegean . Oxford University Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0-19-536550-4 , pp. 752-761.

- ↑ This chapter follows Palyvou 2005, unless otherwise stated

- ↑ a b c Nanno Marinatos: Minoan Threskeiocracy on Thera. In: R. Hägg, N. Marinatos (Ed.): The Minoan Thalassocracy: Myth and Reality. Proceedings of the Third International Symposium at the Swedish Institute in Athens. Stockholm, Paul Åström, 1984, pp. 167-178.

- ↑ a b This chapter follows the presentation in Doumas 2001.

- ^ Thera Foundation: Composition and Provenance Studies of Cycladic Pottery with Particular Reference to Thera. ( Memento from October 27, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Doumas 1991, p. 88.

- ↑ Μουσεία / Προιστορική Θήρα. www.santorinigreece.gr, accessed December 7, 2013 .

- ↑ Christos G. Doumas: The early history of the Aegean Sea in the light of the most recent archaeological finds from Akrotiri, Thera . Society for the Support of Research in Prehistoric Thera, Athens 2008, ISBN 978-960-98269-2-1 , p. 37-41 (In the translation "Statuette of an ibex" - Greek χρυσό εδώλιο αιγάγρου , golden wild goat idol '; in the Aegean there were and are different species or subspecies of the wild goat ( Capra aegagrus ) ).

- ↑ a b c The description of the finds on and below the cenotaph place is based on Christos Doumas: Chambers of Mystery. In: NJ Brodie, J. Doole, G. Gavalas, C. Renfrew (Eds.): Horizon - a colloquium on the prehistory of the Cyclades . Cambridge, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 2008, ISBN 978-1-902937-36-6 , pp. 165-175.

- ^ JW Sperling, Thera and Therasira - Ancient Greek Cities, Volume 22 , Athens Technological Organization, 1973, without ISBN

- ↑ Carl Knappelt, Tim Evans, Ray Rivers: Modeling maritime interactions in the Aegean Bronze Age. In: Antiquity , Volume 82, No 318, December 2008, pp. 1009-1024, 1020.

- ↑ Forsyth, pp. 46f.

- ↑ Marisa Marthari: Raos and Chalarovounia: preliminary evidence from two new sites of the Late Cycladic I period on Thera. In: ALS - Periodical Publication of the Society for the Promotion of Studies on Prehistoric Thera. Volume 2, 2004, pp. 61-65, ISSN 1109-9585

- ↑ Barry PC Molloy: Martial Minoans? Was as Social Process, Practice and Event in Bronze Age Crete. In: The Annual of the British School at Athens , Volume 107 (November 2012), pp. 87–142, 94 f.

- ↑ Elefteria Paliou: The Communicative potential of Theran Murals in Late Bronze Age Akrotiri - Applying viewshed analysis in 3D Townscapes. In: Oxford Journal of Archeology. Volume 30, Issue 3 (August 2011), pp. 247-272, 267 f.

- ↑ Forsyth, pp. 40f.

- ↑ Carl Knappett, Irene Nikolakopoulou: Colonialism without Colonies? A Bronze Age Case Study from Akrotiri, Thera. In: Hesperia. American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Volume 77, Issue 1 (2008), pp. 1–42 [37ff]

- ↑ This chapter follows Floyd W. McCoy / Grant Heiken: The Late-Bronze Age explosive eruption of Thera (Santorini), Greece. Regional and local effects. In: Floyd W. McCoy / Grant Heiken (Eds.): Volcanic Hazards and Disasters in Human Antiquity . Geological Society of America Special Papers 345, Geological Society of America, 2000, ISBN 0-8137-2345-0 , pp. 43-70, (also online , PDF; 3.21 MB).

- ↑ Christos G. Doumas: Thera, Pompeii of the ancient Aegean . Thames and Hudson, 1984, ISBN 0-500-39016-9 , p. 157.

- ↑ Unless otherwise stated, all information in this chapter follows the presentation in Morgan 1988.

- ↑ a b c d e Anne P. Chapin: Frescoes. In: Eric H. Cline (Ed.): The Oxford handbook of the Bronze age Aegean . Oxford University Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0-19-536550-4 , pp. 223-236.

- ↑ Doris Marszk: Canaanites wanted to be like Minoans. www.wissenschaft-aktuell.de, November 10, 2009, accessed on April 20, 2012 .

- ↑ T. Pantazis, AG Karydas, Chr. Doumas, A. Vlachopoulos, P. Nomikos, M. Dinsmore: X-Ray Fluorescence Analysis of a Gold Ibex and other Artifacts from Akrotiri. ( Memento of October 11, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Presented at the 9th International Aegean Conference: Metron, Measuring the Aegean Bronze Age at Yale University, April 18-21, 2002.

- ^ A b David Blackman: Minoan Shipsheds. In: Skyllis, Zeitschrift für Unterwasserarchäologie, Volume 11, Issue 2 (2011), pp. 4–7.

- ↑ Angelia Papagiannopoulou: From Ports to Pictures: Middle Cycladic Figurative Art from Akrotiri, Thera. In: NJ Brodie, J. Doole, G. Gavalas, C. Renfrew (Eds.): Horizon - a colloquium on the prehistory of the Cyclades . Cambridge, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 2008, ISBN 978-1-902937-36-6 , pp. 433-449.

- ↑ C. Michael Hogan: Akrotiri. Ancient Village / Settlement / Misc. Earthwork. The Modern Antiquarian, December 13, 2007, accessed December 9, 2013 .

- ↑ Karin Schlott: The Minoan Ape Mystery. Spectrum of Science , January 21, 2020 .

- ^ Thera Foundation, The House of the Ladies ( Memento from April 3, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Thomas F. Strasser: Location and Perspective in the Theran Flotilla Fresco. In: Journal of Mediterranean Archeology . Volume 23, No. 1 (2010), doi: 10.1558 / jmea.v23i1.3 , pp. 3-26.

- ^ A b c Andreas G. Vlachopoulos: The Wall Paintings from the Xeste 3 Building at Akrotiri: Towards an Interpretation of the Iconographic Program. In: NJ Brodie, J. Doole, G. Gavalas, C. Renfrew (Eds.): Horizon - a colloquium on the prehistory of the Cyclades . Cambridge, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 2008, ISBN 978-1-902937-36-6 , pp. 451-465.

- ^ Badisches Landesmuseum Karlsruhe (ed.), Cyclades and Ancient Orient - inventory catalog of the Badisches Landesmuseum Karlsruhe, Badisches Landesmuseum, Karlsruhe, 1997, ISBN 3-923132-53-0 , K12 + K13

- ↑ Eva Alram-Stern (ed.): The Aegean Early Period - Series 2, Research Report 1975–2002, Volume 2., The Early Bronze Age in Greece with the exception of Crete . Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 2004, ISBN 3-7001-3268-9 , p. 901.

- ↑ Jürgen Thimme, The religious meaning of the cycladic idols. In: Association of Friends of Ancient Art, Ancient Art , 8th year 1965, issue 2, Urs Graf Verlag, Olten, Switzerland, pp. 72–86.

- ↑ Panayiota Sotirakopoulou: The Early Bronze Age Stone Figurines From Akrotiri on Thera and Their Significance for the Early Cycladic Settlement. In: The Annual of the British School at Athens . Volume 93, 1998, ISSN 0068-2454

- ↑ Christos G. Doumas: Managing the Archaeological Heritage: The Case of Akrotiri, Thera (Santorini). In: Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites. Volume 15, No. 1 (2013), pp. 109-120, 113-117.

- ^ Prehistoric Thera Museum. Greek Ministry of Culture, accessed January 11, 2009 .

- ↑ Santozeum.com: The Wall Paintings of Akrotiri (accessed January 9, 2013)

Coordinates: 36 ° 21 ′ 4.9 ″ N , 25 ° 24 ′ 12.8 ″ E