Brown coal in Hürth

The lignite in Hürth and the industry based on it in the Rhenish lignite district , with its changes in the structures in the landscape and society, was one of the reasons for the formation of the then large community of Hürth from the Hürth mayor in 1930. It played for over a hundred years until the last one was dismantled In 1988 coal played its first role in economic life. But traces and documents from the early modern era can still be found today that testify to economic activity with lignite . Even after the end of mining, the chemical industry, which is based on the cheap energy of lignite, and the Hürth power plants, especially the Goldenberg power plant , which supplies a large part of the city with district heating, characterize the place in the current Knapsack Chemical Park . The history of lignite mining is reflected in the street names of Hürth and in some cases also visible in the area.

Beginnings

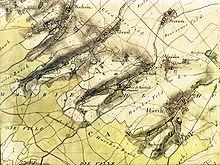

The lignite is cut in the area of the eastern Villehanges by the Hürth brooks , in particular by the Duffesbach in the Hürther Tälchen, sometimes groundwater stored in the seams also escapes in spring horizons above the clay clays on the slopes and valleys. These areas are called Broich: south of Hermülheim was the Faulbroich , in (Alt-) Hürth the Ölbruch (= Uhl = potter) and many more. With the mining of clays and hillside loam, the lignite also came to light. In the course of the economic boom after the Thirty Years' War , firewood became scarce, and attempts were then made to dry and use coal called turf . Along the valley slopes of the source brooks of the Duffesbach and the other Hürth brooks on the land of the landlords and with their permission, hollows were driven into the slopes and the turf was dug up to the groundwater with hoes and spades. On a colored map of the Kentenischer Dorffkaulen from the year 1769, which served to represent the catchment area of the Duffesbach, which is important for the craft businesses on the Cologne brooks , 22 such pits are shown in the Kendenicher and in the Hürth Highness . On a map from 1750 about clearing near Knapsack, there is even an open-pit-like Kentenischer Tourfgrub between the Zülpicher Strass (Luxemburger Strasse) and the Kendenicher or Kranzmaar-Bach towards Knapsack, as well as an Alt Tourff Kulle in the Commenderie-Wald , an abandoned mine see, possibly the forester's pit , in the forest below Knapsack the Hermülheimer Kommende des Teutonic Knights , the third landlord (apart from the churches and monasteries) in the Hürther Tal, between Hürther Bach (Duffesbach) and the path from Hürther Bo leading to Knapsacks Capell [l] the courtyard , today's Kapellen / Industriestrasse. Above Gleuel , on the southern slope of the Gleuel brook, the Hermülheim innkeeper and toll collector Hermann Dümgen leased an open pit on the land of the Cologne cathedral chapter around 1751 , which later became the Gotteshülfe pit . The map of 1751 already shows a drainage that these first right dehydrated surface mining in the Rhenish mining area to Gleueler Bach back. The excerpt from the tranchot map of Mairie de Hürth in the Frechen sheet shows both the Dümgen pit with its drainage as well as the clearly frayed creek slope south of Hürth and the rather large Kendenicher Kuhle.

In 1812, at the time of French rule in the Rhineland , all mines were subjected to the mining law of the Civil Code and recorded for tax reasons . At that time (apart from the above-mentioned mines that were no longer in operation) there were the following companies on areas of 0.1 to 0.6 km² and operated by 3 to 18 day laborers with a yield of 180 to 437.5 t: Wilhelm Fischenich, Hürth; Johann Meul, Berrenrath; Wilhelm Schilling and others, Gleuel; Society Engelbert Schauff and others, Zieskoven (formerly between Alstätten and Gleuel) and Rodius, Fischenich. Only three with 12 to 18 workers managed 1200 and 1350 t per year, the mine at the Pescher Höfe, the "Pescherwerk" by Peter Rolshoven, the mine by Emanuel Scholl and the company mine by Johann Antweiler, Hürth). The Fischenich mine later opened in the Hürtherberg , Schilling, Antweiler and Meul in the Gotteshülfe , Rodius in the Weilergrube and the Schauffsche area was included in the Theresia.

First concessions

During the French era, the assets of the church bodies were expropriated ( secularization ) and were up for sale or auction. This gave many wealthy or rich people the opportunity to acquire and cultivate new land and then dig pits on their own land. A possibility of digging in foreign land was only made possible by the later Prussian mining law . Initially, French law continued to apply (finally changed in 1865). Emmanuell Scholl, the son of Karl Josef Scholl , the Maire von Hürth, applied for the first official concessions in our area in 1813 for 22 hectares. The application was no longer approved because of the end of the French era . The second applicant, already with the Prussians , was the lord of the castle of Aldenrath , Karl Josef Freiherr von Mylius , who was the first Prussian mayor of Cologne at the time, for his land above the Dümgens mine. The Myliusgrube was soon shut down and only 140 years later it was charred from the Gotteshülfe mine . The previously existing pits usually remained. Scholl then applied for the license again in 1824, but for a larger area, the later Theresia (95.9 ha). He also wanted to take over the Pescherwerk and was planning further concessions with over 250 ha. The widow Rolshoven insisted on hereditary rights and on November 24, 1824 received the concession for her 4.5 ha but only "down to the groundwater", including Scholl who built a drainage tunnel for his pit. This was a unique mining law construct. What if the level sank due to the neighboring mining? But problems did not arise because Scholl did not mine nearby for the time being. On a map from 1831 based on the Prussian inventory of 1816, the following pits are drawn in for our area: The hamlet pit above Fischenichs near the Weilerhof, the Hürther Berg with the Franziska field at the height and the pit of the Hürth landlord, von Wolffen, at the exit of the Hürther Tälchens that the Cologne merchants Ritter and Renner bought together with Burgland (concession from 1822). On the other side of the valley, the Alstädter Berg, was the Scholls Grube from 1824, the Emmanuel Scholl, French "tax collector" and son of the Hürth mayor and former operator of the Cologne lottery company, Carl-Josef Scholl († 1809), named after his wife Theresia, born from the race, called Grube Theresia . The Rolshoven family's Pescherwerk remained in existence. In front of Berrenrath , in the basin of the Burbach, was the small Koepsgrube (concession for Berrenrath Peter Koep from October 24, 1819), which was later named Grube Engelbert by his son, Berrenrath mayor Engelbert Koep . The Gleueler Grube Gotteshülfe is also listed. Many smaller, also abandoned or disused excavation sites on their own land may not have been worth the fuss. But even the larger pits only employed a few day laborers, mostly only during the time when the field work was idle. In 1857 the Commenderie mine in the former Kommendewald was licensed for the brewer Firmenich. It was used for the production of Klütten until 1872 , after that only for the operation of the brewing kettle of his brewery (today tennis court area, the vaults still exist today). Firmenich obviously also used a pit on the other side of the Hürth brook, which is shown on the official maps. The pits often changed hands or were even completely idle and went bankrupt, as mining and sales in the immediate vicinity did not bring any real profit. One often reads that mine fields were consolidated (merged) in order to work more economically, a development that ultimately led to the large corporation RWE Power .

Scholl did not yet dare to take the step to large-scale opencast mining. His mine continued to operate Tummelbau with (1830 to 1848) 11 to 25 workers and 2000 to 5500 tons of coal annually. Nevertheless, his operation was the most successful, what you could see in his villa, which was only demolished around 1980 (now Ramada Hotel). His son Joseph then gradually started mining in 1855 and also began to modernize, which brought the company into the red. In 1860 production fell to around 600 tons. Joseph Scholl died childless in 1879. Nieces and nephews tried to keep the mine going. In 1855, around 6000 t of raw lignite were extracted in all the mines in the Hürth area, an amount that 100 years later came together in just under two hours.

Industrialized mining

On March 1, 1877, the first briquettes were pressed using the Carl Exter method on the Roddergrube in Brühl . So far, only so-called wet stones had been formed similar to bricks, which had to be air-dried and which burned only a little better than the previously hand-formed blocks . In addition, machines for mining overburden and then for mining and transporting the coal came into use.

Rhineland mine and Ribbertwerke

The first briquette factory in the Hürth area for wet stones was built in Hermülheim in 1884 for a field between Luxemburger Straße and Kendenich, which was already awarded in 1867, by Emil Sauer together with the entrepreneur Moritz Ribbert from Hohenlimburg and until Sauer left the Rhineland in 1886 It was connected to a brick and clay pipe factory. He had himself registered as a trademark with a Sternbrickett (later Ribbert ). As early as 1886, three steam-operated extra presses with six tube dryers were introduced. In addition, Ribbert was able to sell the overburden over the coal for the construction of the railway systems to be raised around Cologne Central Station . Ribbert had acquired concessions from Sauer all the way to Brühl. The decision for Hermülheim was made because of its proximity to the state railway in Kalscheuren , to which Ribbert was connected in 1888. This subsequently served as a Villebahn for the later and other works in the Hürth area, ultimately even for fields on the other side of the Ville near Türnich . The Kendenich field was charred in one year, the Franziska I field above, which was largely acquired after laborious negotiations by the manor owner von Kempis, Kendenich , in ten years. The slopes of the pit fields, some of which are planted with undemanding robinia and other trees, are clearly recognizable in the agriculturally recultivated area east of Luxemburger Straße, as is the steep slope to Kendenich's Frenzenhofstraße. Then the Ribbert factory was supplied with coal from the Engelbert mine near Berrenrath with the help of a cable car over (Alt-) Hürth, next to Trierer Straße. In 1920 the mine and factory were taken over by the Eschweiler Mining Association . After the Engelbert mine was burned out, the work was taken over by the Roddergrube and the cable car was extended to its Berrenrath field . The factory and the cable car were in operation until a bomb hit in 1944, which completely destroyed the factory. The area is now used by a small shopping center. The area of the pits, which has been re-cultivated except for the edges of the pits, is easily accessible from all sides by paths. The best access is via the Römerkanal hiking trail opposite the confluence of the Trier and Luxemburger Straße. Since the soil quality is not particularly good job on a part of the land, they were within the EU - aside to grassland broke converted. With the hedges and tree plantings on the pit edges, they are an ideal habitat for the bird world.

Theresia mine

1882 was Theresia in a 100-piece union (250,000 Mark) is converted to Scholl led by Viktor Scholl, a former professional officer, possessed of which only 17 Kuxe , which was then expanded in a 1000-piece to 400,000 marrow to to build a brick factory and a briquette factory. The briquette factory with only two presses could not be financed with a loan until 1891. Viktor died in 1895 and the company finally went downhill. In the coal crisis after 1901, the plant was shut down in 1905 due to unprofitability and the union went bankrupt. The last owner became the Rheinische Braunkohlen-Briquettwerke sales association in 1908 after several changes. Ultimately, the field ended up in the Rheinbraun / RWE Group. The factories were subsequently demolished. The Hürth sports facilities were built in the charred area in 1937/39. The rest of the Theresia mine fields up to the Knapsack industrial hill were not prepared for further mining until 1965 after the Gotteshülfe mine was re-opened in 1951 and then charred for twelve years from 1971 to September 1983. The two bucket chain excavators previously used in the Gotteshülfe mine with the internal numbers 101 and 102 with 9,000 cm³, built in 1949 and 50 from the Lübecker Maschinenbau Gesellschaft and a pre-war model from 1935 by the Krupp company , the bucket chain excavator 197 with a daily output of around 39,000 cm³, were added Commitment. In addition, there was the only LMG bucket wheel excavator in the Hürth pits, No. 263 from 1952 with 10,000 cm³ and an LMG spreader (No. 725) from 1949. All equipment was dismantled and scrapped on the spot after the pit ran out. Smaller parts are set up as an industrial monument at the town hall. Overburden and coal were transported to the stacker and the Goldenberg power plant via a 900 mm track . A model train with an electric locomotive from 1948 is looked after as a memorial by a support association.

United Ville

In 1868, seven adjacent concession fields were awarded to the Mayor of Brühl, Engelbert Poncelet , on the villa height above Knapsack , but they were not used due to the lack of traffic. It was not until 1901 that the entrepreneur and main trades of the Brühler Roddergrube , Friedrich Eduard Behrens , dared a new beginning, united the fields to the United Ville , opened the field and built the first briquette factory. In 1906, however, he had to merge his new trade union and its co-partners with the Roddergrube, which had already acquired fields at Berrenrath. The railway connection took place in 1903 via the Ribbert / Theresia connection as the later Villebahn . This enterprise should bring the success of the brown coal industry. In 1906, the company concluded coal supply contracts with the calcium cyanamide plant in what is now the Knapsack Chemical Park, as well as with the RWE large-scale power plant , later named after its builder, the Goldenberg plant , in 1912–1914 . In addition, the briquette factories were expanded to last five factories (with Berrenrath six), of which the most recently built is still the only one of its kind in Hürth as the coal refining company Ville / Berrenrath mainly producing lignite dust for large industrial combustion plants. The increase from the recultivation around Bleibtreusee to Knapsacker Hügel with its industrial plants is still impressive today . The Ville mines and the Berrenrath open- cast mine , which was opened in 1913 , were subsequently expanded to include the Ville State Forest and, through the acquisition of older fields, towards Türnich and Frechen (Schallmauer / Gotteshülfefeld). The main field Ville was dismantled until 1976, a remaining field on the southwest corner of Knapsack was dismantled again from 1983 to 1988 (only as particularly pure briquette coal). Until 1976, the coal was driven by electric narrow and full-gauge railways, the tracks of which followed the excavation edge (in the remaining field with conveyor belts). The way from the pit to the factories was initially via three chain tracks from 1925 for the open-plan cars with electric locomotives and then from the pit via two inclined elevators , each with 18,000 t per day. The dismantling was carried out using bucket chain excavators , which could be used both in deep and high cut (viewed from the chassis level), and there were also cutting excavators . Large bucket wheel excavators have not yet been used in Hürth. The first belt stackers were also used here.

Huertherberg

The last independent industrial lignite mine with a briquette factory was built in 1908 on the old field of the Hürth lords of the castle, later Ritter and Renner, whose mining was carried out despite newly applied for licenses (1815, approved in 1822, extension approved in 1841, production between 1830 and 1860 on average around 1000 t per year with a workforce of around 5 to 20 men) has been almost completely inactive since the 1870s, and which had been sold by the last owners to the Werhahn family on May 25, 1906 as the Hürtherberg trade union with 850,000 marks in 100 kuxes and with five trades ( including Werhahn with 30 Kuxen) and an industrial bond at 5% of another 1.2 million marks, newly built. It was also connected to the Ribbertsche Bahn. The union's ownership changed in the 1920s (1933) to the United Steelworks .

Since the space in the first mining field was very narrow, the overburden had to be tipped up with steep slopes facing the Duffesbach. These steep slopes were immediately planted to ensure stability. The forest area with a lake in the open pit , which is named after Adolf Dasbach , the plant's pioneer work in recultivation (1919 until it was closed in 1960) , the recultivated old pit and the Kipp are now the Hürtherberg recreational area as a landscape protection area . The forested part around the former factory was classified as a protected landscape area . The Hürth plant section of the Knapsack Chemical Park was also laid with special foundation measures in a refilled part of the Hürtherberg pit on the other side of Bergstrasse and west of the Luxemburger Strasse that was moved into the backfilled pit. The United Ville concession was connected to the mine to the south and west.

The pits on the northeast slope of the Ville all mined a seam that was only covered with a small layer of overburden but was only 3 to 6 meters thick and was often interspersed with intermediate materials of sand and clay. As a result, they often struggled to be profitable . Only after the Kierberger Sprung (Frechen-Knapsack-Kierberg) did the 40 to 75 meters thick main seam set in (north of the Cologne Aachen railway line up to 100 meters) with a thickness of about 12 meters above the coal and the best, pure lignite, which was particularly special was suitable for briquettes (→ Geology of the Lower Rhine Bay ).

Since the mine south of Trierer Strasse was soon charred, the concession was extended in 1914 to include the mining fields "Franziska" south of the Ribbertgrube and "Vereinigte Wilhelmsglück" on the other side of Luxemburger Strasse and then in 1915 to the field "an der Kranzmaar" from Kendenich to Nach Brühl- Heide . There the seam was thicker and interspersed with fewer intermediate resources. Even when electric narrow-gauge wagons were moving coal (and overburden) on the Ville for a long time , the coal was transported to the factory with the help of a chain train that ran through a tunnel under Luxemburger Strasse . The last field was charred by December 1960. The overburden was brought to the other side of the mining trough by means of a steel conveyor bridge , where it was tipped and directly recultivated. The mechanization of mining and the increase in production with the last nine single and three double presses up to almost 200,000 t per year took place continuously. In 1961 the Kuxe was taken over by Rheinbraun and the factory was demolished. Remnants can still be seen in an area left to itself behind the Hermülheim fire station. It is also worth mentioning that the plant's generators were the first and only ones to supply electricity to part of Hürth, particularly the hospital, after the American occupation in 1945.

Fringing fields

The pit fields that were opened up by the neighboring communities, but extended to the community area, should also be mentioned: The Schallmauer pit on the border with Bachem , Louise ( Türnich ) and Bleibtreu ( Köttingen ).

Mining settlements

Significant mining settlements can be found in Gleuel around Barbara- and Bergmannstrasse , in the Berrenrath settlement completed in 1946 (the part of Berrenrath that is on charred and in 1919 refilled land, which was connected to the original location) around Glückaufstrasse next to the Coal refining company Ville / Berrenrath on the Villenhöhe, earlier also in Knapsack and on Villestrasse next to the Berrenrath briquette factory (built in 1914). RWE settlements for the power plants were in Alt-Hürth (Clementinenhof ((monument protection)), Mühlenstrasse, Firmenichstrasse and Kreuzstrasse) and in Efferen around Hertzstrasse. There is also an old RWE settlement in the Hermülheim district (Thiel-, Lessing- and Hans-Böckler-Str. In the flower settlement). The site-related chemistry (formerly Hoechst AG , today Knapsack Chemical Park ) had its senior civil servant colony , which is now a listed building, around Dr.-Krauss-Straße (plant manager since 1912) in Knapsack, which was not relocated.

Resettlement

It soon became apparent that the smaller hamlets and districts would have to be relocated in order to systematically and completely dismantle the slowly exhausting mine fields. The Ursfeld , Zieskoven and Aldenrath settlements (mainly to Gleuel Neuzieskoven ) were the first to be relocated around 1936 between Hürth and Gleuel . In the 1950s (1952–1959) the closed resettlement of Berrenrath took place on the site of the recultivated Aldenrath field , where the hamlet of Aldenrath used to be. The formerly continuous development on Alstädter Straße (from Alt-Hürth) was demolished and dredged away in the 1970s. Today's Alstädter Strasse only goes as far as the new bypass road in the charred Theresiafeld, Frechener Strasse. Most of the resident population in Knapsack was resettled for reasons of environmental pollution , not because of the lignite, but because of the dust and exhaust gas pollution of the power plants and chemicals at the time. The road network with the old names was partially preserved in the Knapsack industrial area. In Knapsack there is the only church and school street in the city of Hürth but neither a school nor a church (the other church streets were renamed Severinusstraße, for example).

Road relocations

The most important road relocation is the relocation of the once dead straight Roman road Trier – Cologne , the Luxemburger Straße, into the recultivated opencast mine of the Hürtherberg. The former route is still recognizable in the different vegetation of the forest areas in the recultivated pit west of the new road. The old Agrippa-Straße Cologne – Trier should also be made recognizable again by suitable measures in the area in which it was excavated. There was enough space in the filled open-cast mines for modern road layouts, which benefits the users of the Federal Motorway 1 and the many new connecting or bypass roads between and around the Hürth districts.

Reclamation

After some of the fields between Kendenich and Hermülheim had been recultivated for agriculture before the Second World War and the Hürtherberg under Adolf Dasbach had done pioneering work in its pit (a hiking trail leads through the forest recultivated areas between Kendenich and Heide), the Hürther Mitte was able to join the Otto-Maigler-See , a sports and swimming lake, and the adjacent nature reserve Hürther Waldsee . On the agriculturally recultivated Berrenrather Börde, a rural hamlet was created in 1965–1971. The last charred area near Knapsack, the Ville Nordfeld, is left to its own devices as a nature reserve. The garbage dump of the city of Cologne and the ash dump of the Hürth power plants extend south of Knapsack in the new villa forest. Fortunately, the plan to set up a toxic waste dump there could not be pursued. The landfills will be gradually covered and greened.

Afterlife in street names

The dismantled Villebahn still lives on in the street name An der Villenbahn in Alt-Hürth. The following streets go back to old mine fields: To Roddergrube in Berrenrath, Engelbertstraße in the industrial area Knapsack, Hürtherberg- and Schollstraße are side streets of Duffesbachstraße near the old location of the briquette factory Hürtherberg, the street Zur Gotteshülfe leads to today's Otto-Maigler-See , the remaining hole in the pit. The Theresia Road and Theresienhöhe lie above the shopping center. The Adolf-Dasbach-Weg at the youth hostel in Kendenich, the Behrensstrasse and the Von-Mylius-Strasse in Berrenrath and the Ribbertstrasse at the southern end of Hermülheim are named after personalities . There, Eschweilerstraße is also a reminder of one of the former owners of the Ribbertwerke, the Eschweiler Mining Association . The Schollstraße not only reminiscent of the old mine, but also from the first owner, the mayor Hürther family Scholl .

literature

- Walter Buschmann , Norbert Gilson, Barbara Rinn: Lignite mining in the Rhineland. ed. from LVR and MBV-NRW , 2008, ISBN 978-3-88462-269-8 .

- Fritz Wündisch : From Klütten and Briquettes, pictures from the history of the Rhenish lignite mining. Reykers, Weiden 1964, DNB 455765790 .

- Further literature in the article Hürth, in the district articles and in the Rheinisches Braunkohlerevier

Web links

- Uni-Greifswald: measuring table sheet Brühl 1893 reduced old measuring table sheet (sheet 5107 Brühl)

- Table sheet Kerpen (5106 from 1902) Alt-Berrenrath, Ursfeld, Aldenrath

- (Bruehl 1933)

Individual evidence

- ↑ The maps from the Historical Archive Cologne , reduced in size last shown in: Walter Buschmann, Norbert Gilson, Barbara Rinn: Brown coal mining in the Rhineland. ed. from LVR and MBV-NRW . Wernersche Verlagsgesellschaft, Worms 2008, p. 37 u. 268.

-

↑ Files of the Département de la Roer in the State Archives North Rhine-Westphalia Rhineland Department in Düsseldorf (Find no .: 2551, Bl. 89f., 120f.

Quoted by Erik Barthelemy: Die Franzosen in Hürth. In: Hürther Heimat. Vol. 83, p. 37f. - ↑ Barthelemy: The French in Hürth. P. 38.

- ^ Fritz Wündisch: from Klütten and Briquettes. 1964, p. 51.

- ↑ Article: The Hürther Klüttenkaulen and KLüttenfabriken in Egon Conzen: 800 years of Alt-Hürth Ed. Ortgemeinschaft Alt-Hürth, Stohrer Druck, Hürth 1985

- ↑ Buschmann et al.: Brown coal mining in the Rhineland. 2008, p. 40.

- ^ Hermann Plog: Chronology Berrenrath. In: Dorfgemeinschaft Berrenrath (Ed.): 50 years of resettlement Berrenrath. 2009, p. 16.

- ↑ Conzen p. 48 f

- ^ Fritz Wündisch: Brown coal, power source of the Hürth area. In: Kölnische Rundschau (ed.): 25 years of the large community of Hürth. Cologne 1955, p. 23.

- ↑ Fritz Wündisch: From Klütten and Briquettes. 1964, p. 110.

- ↑ Klemens Klug: Die Vorläufer der Ribbertwerke , in Hürther Heimat 65/66 (199), pp. 59-76.

- ↑ so Clemens Klug: Hürth - how it was, how it became , Steimel Verlag, Cologne o. J. (1962) p. 195

- ↑ Conzen p. 50 ff

- ^ Plog: Chronology Berrenrath. 2009, p. 22.

- ↑ Buschmann et al.: Brown coal mining in the Rhineland. 2008, p. 322 and 276

- ↑ Chronicle in Hürther Heimat No. 51/52 (1984), p. 105

- ↑ lr.online with a comparable model from the Senftenberger Revier

- ↑ Karl-Heinz Draaf: Brown coal excavator and stacker in the Theresia opencast mine , in Hürther Contributions Vol. 91, 2012, pp. 45–54 (with illustrations and construction drawings)

- ↑ Report Rhein-Erft-Rundschau from September 11, 2015, online

- ↑ Buschmann, pp. 149 and 314

- ↑ Buschmann et al.: Brown coal mining in the Rhineland. 2008, p. 398.

- ↑ Hans Desery: Brown coal open cast mining on Hürther Berg in Hürther Heimat 73 (1994), pp. 64–96.

- ↑ Hans Conzen: 800 years old Hürth , section Hürther Berg , pp. 54–59

- ^ Plog: Chronology Berrenrath. 2009, p. 21.

- ^ Plog: Chronology Berrenrath. 2009, p. 19.

- ^ Plog: Chronology Berrenrath. 2009, p. 21.

- ^ Plog: Chronology Berrenrath. 2009, p. 25 f.