Damau

Damau ( Hindi दमाऊ ) also damaū, damaung, dhamu, dhmuva, is a flat kettle drum with a metal body that is played in Indian folk music in the Garhwal and Kumaon regions in the northern Indian state of Uttarakhand together with the larger barrel drum dhol . The drum pair with the damau as the higher-sounding accompaniment of the dhol forms the basis for the ceremonial and entertaining music outdoors in contrast to the hourglass drums hurka or daunr , which alternatively together with the brass plate thali form the pair of instruments used for music in closed rooms. The dhol-damau players are mainly used for the Pandavalila dance theater, which is associated with obsession rituals, and for wedding ceremonies in which the drumming group is reinforced by two bagpipes mashak as the only melody instruments.

Origin and Distribution

It is difficult to connect the extremely large number of drum types that exist in India with the names for drums (Sanskrit generally avanaddha ) which have been handed down in Sanskrit and Tamil since ancient times . Some ancient Indian drum names refer to the use or meaning and not to a specific form, for example tyagu-murasu , "drum of generosity" and vira-murasu , "drum of heroes". Most ancient Indian drums have a magical, salvific meaning either in a military or in a religious context. In Vedic texts from the 1st millennium BC The name dundubhi is often used for a war drum. In the text collection Taittiriya-Samhita , a certain Shaka (an interpretation or school of the Vedic scriptures), it is mentioned that the body of the dundubhi was made of wood, but not whether it was a single-headed kettle drum or a double-headed tubular drum . P. Sambamurthy (1952) describes the dundubhi in his lexicon on South Indian music as a "large conical drum" with a body made of mango wood, which produced a loud and terrifying sound when struck with a solid, curved stick ( kona ).

Nevertheless, Indian kettle drums have been proven beyond doubt long before the Islamic conquests in the Middle Ages. A soapstone relief from the 1st century AD, belonging to the Buddhist-Hellenistic art of Gandhara , shows a series of standing figures bringing wine in jugs and animal skins and in the middle a woman with a palm branch, next to whom a man is with beating a kettle drum clamped between his thighs in his hands. Its spherical body appears to be made of clay and is reminiscent of clay drums still played in regional folk music today, such as the ghumat in Goa . The tumbaknari in cashmere is a tumbler drum made of clay. More known than such clay drums in ancient and modern India are clay pots ( idiophones ) with a narrow opening without a membrane like the ghatam . The name dundubhi occurs in Rig Veda , subsequently in the great epics Mahabharata and Ramayana , in the Buddhist Jatakas and in Natyashastra , the most important ancient Indian treatise on the performing arts. A word that is equated with dundubhi is bheri (in today's Tamil perikai ), which is often mentioned in Jatakas. The Bherivada Jataka has the drum name in its title.

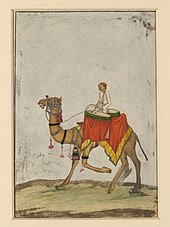

Curt Sachs (1923) considers the kettle drums played in pairs in India - and the drums of the cavalry regiments in Europe from the late Middle Ages - to be an invention of Persian cavalry armies, which could hardly use a double-headed drum on horseback and instead use it for reasons of symmetry and weight distribution Horse hung two connected kettle drums around the neck so that they did not hinder the player who hit them with sticks while riding.

It is possible that the first kettle drums from the Middle East reached India after the first Arab conquest of Sindh in 712, together with long trumpets, cone oboes and other instruments of the military bands. The Arabic name naqqāra (in the spelling nagārā and similar) for a large pair of kettle drums has been known in India since the establishment of the Sultanate of Delhi in 1206 and initially referred to a military drum. Soon the nagārā became a leading instrument in the great ceremonial palace orchestras naqqārakhāna or naubat . The nagārā pair of drums consisted of a high-pitched and a low-pitched kettle drum. This combination corresponds to the tabla, which is widely used in Indian classical music and popular music . In the court chronicle Ain-i-Akbari of the Mughal ruler Akbar from the end of the 16th century, a huge, almost man- high pair of kettle drums called kurka is described, each drum being struck by a musician with two sticks. The kurka was one of the ruler's insignia and was heard when his edicts were announced. In addition, according to this chronicle, there were other kettle drums with the names naqqāra, kūs and damāma .

The damāma (or kuwarga ) was a very large pair , the naqqāra a smaller pair of kettle drums in the naqqārakhāna , which, as listed in the Ain-i-Akbari, consisted of 63 instruments, two thirds of which were drums. There were also long trumpets ( karna and nafir ), cone oboes ( surna , later shehnai in India ) and cymbals (Arabic / Persian sanj ). For the 17th century, miniature paintings confirm that kettle drum pairs were the most widely used instruments in naqqārakhāna ( naubat ) during the Mughal period .

The nagārā of the Mughal period still exists today in a reduced naubat ensemble as two small kettle drums with a metal body, which are occasionally played at some Muslim shrines in Rajasthan in northwestern India, including the tomb of the Sufi saint Muinuddin Chishti in Ajmer . The higher-sounding drum on the right is called jil or jhil (from Arabic / Persian zir, cf. Turkish zil ) and the lower-sounding, big drum on the left is called dhāma . The tradition of the naubat seems to have passed into similar ensembles of the Hindu worship practice in front of temples in some places .

In the folk music of Rajasthan, apart from the nagara pair of drums, large single kettle drums are known under the Mughal Indian names dhonso and damama . Damami is the name of the Rajasthani professional caste of traditional drum players. They are considered to be socially inferior caste, even if they trace their origins back to the war drums in the armies of the Rajputs . In Bengal the pair of snare drums are known as duggi . In the extreme north-east of India, the nagra is a single, ritually revered kettle drum that may only be struck during certain rituals. The largest kettle drum that is played individually in what is now northern India is the dhamsa with an iron body.

In Garhwal, the damau is also incorrectly called damama , although the damau is smaller and flatter and is played differently than the kettle drum in Rajasthan. In Garhwal there is a kettle drum that is beaten individually with two sticks, which is much larger than the damau and is called nagara . In Nepal the nagara is a rare pair of drums , while the damaha , which occurs mainly in central Nepal and is played with one or two sticks, is similar in shape to the nagara of Rajasthan and Garhwal.

Design

The damau has a flat, bowl-shaped body made of copper, brass or iron sheet with a membrane diameter of about 30 centimeters. The height of the body is about half the diameter. Some drums have a round opening at the bottom with a diameter of 11 centimeters. The upper edge of the drum is not always exactly circular. The membrane consists of deer or buffalo skin, it is pulled over the opening in the body and tied with strips of skin or intestine, which are cross-shaped or otherwise linked, with a ring on the bottom made of the same material. Two skin loops are attached to the lacing on one side of the body. A cotton shoulder strap is attached to this, which the standing player puts diagonally around his neck and shoulder so that the drum hangs in the middle in front of his stomach. The membrane is approximately in the vertical position. A seated musician places the drum horizontally in front of him on the floor or at a slight angle against his feet. A damau weighs 5 to 6 kilograms.

The damau is beaten with two thin sticks about 38 centimeters long, which are tapered at the lower end and are slightly curved. Both sticks are clamped with the clenched hand between thumb and forefinger and stick out between the forefinger and middle finger. The hands are close together and the middle of the eardrum is always hit with both sticks.

According to a report from the middle of the 20th century, the damau used to be called batisha (from Sanskrit vasti , "urinary bladder"), probably because of the animal skin used to make it. Another old name, kamchini , referred to a "bell belt " (Sanskrit kanchi ) that was sometimes placed around the drum.

Although the tabla and many other kettle drums are tuned to a specific pitch, this is not the case with the damau , and neither is the barrel drum dhol , with which the damau is always used. With the drum pair dhol-damau , only an audible pitch difference is important. The dhol is the largest and deepest sounding drum in Garhwal. It consists of an approximately 45 centimeter long copper or, more rarely, brass body and has two diaphragms of the same size, 38 centimeters in diameter, made on the right from goat, deer or buffalo skin and on the left from goat skin. The left membrane is hit with the hand, the right with a stick.

The nagara kettle drum, which is much larger and deeper than the damau sounding, is rare in Garhwal today and is only sometimes used in addition to a dhol-damau pair at outdoor festive events. In addition to the dhol , Garhwal's popular music also includes the smaller barrel drums dholak and dholki , whose names are used interchangeably for the same drum.

Style of play

The dhol can also be used without the damau and in other musical forms; conversely, the damau is never used without a dhol . The dhol is the largest drum in Garhwal and, with twelve different types of beat, is considered to be the most musically diverse. In the damau , on the other hand, only two types of punch are performed: with a stick in the left and one in the right hand.

Music box and music styles

In contrast to the rest of India, the society of Garhwal is divided into the two highly caste groups Brahmins and Rajputs and the lower caste of the Shilpkars, which comprises only a tenth of the population. The musicians' castes, which belong to the numerous professional castes ( jati ) within this caste structure, are all assigned to the marginalized lower class with a low income, although certain musicians are indispensable for performing social and religious ceremonies. The traditional musical instruments in Garhwal are divided into two groups: for performance at outdoor events and for indoor performances. All instruments in outdoor performances are played by the Bajgis, the numerically largest caste of musicians. Not all Bajgis are musicians, but the musicians among them mainly play dhol and damau . At events they can perform equally well with both drums. Other instruments that specialized bajgis use are the bagpipe mashak and the curved trumpet ransingha , which is also only played outdoors but rarely, and the straight long trumpet bhankora . The Beda (also Baddi) are responsible for light music , devotional songs ( ausar ) and a dance drama with masks ( swang or pattar ) with dholak and harmonium .

Just as necessary for ceremonies as the Bajgis are a group of instrumentalists who do not belong to any musical caste and who are used for indoor performances. First and foremost, these are the players of the two pairs of instruments hurka (a small hourglass drum ) and thali (brass plate ) as well as daunr (small hourglass drum with a different shape and style of playing) and thali . The daunriya (player of the daunr ) is both a singer and, as a jagariya, the leader of possession ceremonies ( jagar ) in private homes. The jagar performed in the open air with dhol and damau , both privately and publicly, are ancient magical rituals that are connected with the popular belief in bhutas (spirits, demons).

The entire repertoire sung on the different occasions can be divided into gatha (long epic ballads) and lok-git (shorter folk songs) regardless of stylistic or content criteria . In the gatha repertoire, religious jagarn with tales of gods are distinguished from the more secular heroic stories pawada , while the lok-git repertoire consists of mangal-git , auspicious wedding songs , and several group dances for entertainment. In practice, a distinction between gods and heroes tales is often difficult, such as from classical Sanskrit epic Mahabharata acquired stories of the five Pandava -Brüder that are perceived as deified heroes. Known in Garhwal as Pandavalila, these stories are performed using a combination of dance and theater. The theatrical element is provided by actors performing in a public outdoor venue, who also become individual dancers as soon as they have become obsessed with the spirit of the character they embody. In this they resemble the obsession dancers of the ceremonies in closed rooms accompanied by daunr-thali .

With the shorter folk song repertoire lok git belonging mangal-git (of Hindi and Garhwali mangal , "auspicious", "blessing") are meant especially wedding songs. These songs accompany the entire wedding ceremony over long distances, including the day-long preparations, and are invocations to the gods who may take care of the well-being of the bride and groom and their families. Lok-git are also songs that accompany group dances ( chau (n) phala, jhumailo and tharya ); Workers' songs ( bajuband and ghasyari ), which can sometimes also accompany group dances, and a number of other entertainment songs .

The knowledge of the musical styles associated with the dhol as the leading instrument is referred to as Dhol Sagar (literally “sea of the drum”). For the mainly orally transmitted content, some fragmentarily preserved written sources can be used, which, however, consist of a linguistic combination of Hindi, Garhwali and Sanskrit and are not always clearly legible. Since the beginning of the 20th century there has been a lot of secondary literature in which the historical texts are collected and analyzed in order to present the Dhol Sagar tradition complex , which encompasses more than the texts that have been preserved, as a literary unit. This is how many drum players understand the Dhol Sagar tradition, whose mythical texts about the gods make up the effect of the music.

Pandavalila

Pandavalila is a theatrical performance of stories from the Mahabharata , in which dances, obsession rituals and processions accompanied by drum music play an essential part. The audience should be entertained and receive the blessings of the gods. For the Garhwalis, humans and gods dance together for pleasure, guided by the power of drum music and in an atmosphere where religious ritual and entertainment merge. A pandavalila strengthens the relationship between people and the gods and the bond between the village community and migrant workers who return to their village especially for this occasion.

In most of the villages, Pandavalila performances take place at intervals of several years, always after the harvest time, from late October to early December; they last between a few consecutive days and up to a month. The place in the village where the performance takes place, identified by a makeshift shrine of gods, is called mandan , like the ceremonial activities themselves . After the opening with a sacrificial ritual at the shrine, a group dance ( chaunwara ) begins either by the Pandava performers alone or together with other residents of the village. The actors always come from the respective village, residents from other villages appear as spectators at larger performances.

Pandavalila , which takes place in the afternoon and evening, is announced by dhol-damau drummers; as a signal for the villagers to come to the place. At the beginning there is an auspicious invocation ceremony ( badhai or barhai ), which is accompanied by the drummers with a constant metric beat. The beat sequences consist of asymmetrical cycles of 29 beats in one performance and first 13, then twice 20 beats on the dhol one after the other. The damau is played with roughly double the number of strokes. Typical of most badhai rhythms are short pauses in the dhol , which the damau bridges with quarter or eighth beats. The dhol then starts again with two clearly distinguishable blows of the left hand on the edge of the membrane.

The chaunwara always starts slowly and ends at a fast pace. The dancers - exclusively high-class men from the village - move counterclockwise in a circle. On the main beat of the dhol , they swing their bodies sideways and bend their knees while slowly turning a little towards the center of the circle. The different drum rhythms for this ( baja ) have a long cycle in common with a meter divisible by 12. Since Pandavalilas are not held annually, it can happen that the participating dancers still act in a coordinated manner in the slow baja , but are not practiced enough for the faster pace.

Towards the end of the last chaunwara dance, the performers get into a state of obsession with a certain deity ( devta ) and show this by turning movements and twitching gestures. They now claim the entire dance floor for their individual performance. Finally they go to the drummers and come to rest directly in front of them or they are held up by an assistant until their trance state has subsided. After the series of obsession dances, other residents of the village can get together for another circle dance. Over the course of several days, an increasingly better choreographed sequence develops and dramatic scenes from the underlying narratives are worked out more clearly.

The most popular is the episode Chakravyu (also Chakravyuha ) from the Mahabharata . This is the name of a military formation in which the opponents in combat come closer and closer in a circle spiral or a labyrinthine figure. Abhimanyu leads the Pandavas to attack this formation built up by the opposing Kauravas . He alone succeeds in penetrating and overcoming the seven gates of the position. When he arrives in the innermost room of the fortress, he is killed by the Kauravas with no possibility of retreat. The fortress labyrinth is marked out on the square with wooden posts and saris donated by all households, i.e. around six meter long lengths of fabric, and Abhimanyu is given a chariot drawn by several people. The entire course of action is accompanied by drums until the end, when all actors line up in a group and the drum players give the final signal to clean up.

Wedding celebrations

The time of the Pandavalila performances is the general festival season, during which Diwali and other public festivals (melas) are also celebrated. The months of the Hindu calendar paush (December / January) and magha (January / February) are particularly beneficial for weddings . Dhol-damau groups are invited to all events during this season . Most drummers know not only the Pandavalila repertoire but also that of weddings. No wedding in Garhwal can take place without dhol-damau . Also, two bagpipes, mashak, are almost indispensable . In the course of the 20th century, they were the only melody instruments to replace the S-shaped curved trumpets ransingha in the village wedding chapels of Garhwals, and they are a widely audible signal that a wedding is taking place. In some cases, instead of the mashak players, a municipal ensemble with brass instruments is hired, but this cannot replace the dhol-damau players. These essentially determine the course and structure of the wedding ceremony.

At least seven days before the wedding day, the bride no longer leaves her home in her village. After various preparations, on the actual feast day, the groom goes in a procession from his neighboring village to the bride's house. Several hours beforehand, dances accompanied by groups of drummers take place in the groom's family on this day. His household deity ( kul devta ) and other gods receive offerings, the bridegroom's sedan chair ( dola ) is decorated with gold and yellow cloths. The procession starts moving with the group of musicians; for longer distances, the journey takes place in a rented bus. As soon as the group of the groom ( brat ) is within sight or hearing range of the bride's village, they pause and the drum players announce their arrival with loud beats. They play a rhythm called shabd , which is characterized by loud, dramatic beats. The last part in front of the bride's house is covered by the group on foot, with the groom being carried in the litter. The procession moves in the course of the journey through different terrain: on a level path or a steep path, which requires specially coordinated drum rhythms ( baja ). An exemplary drum cycle that is played when the group walks up a steep path begins with a cycle of 10 beats on the dhol and 20 constant beats on the damau , followed by a cycle of 14 beats of the dhol and twice as many on the damau . If the path curves, the players fall into a different rhythm.

The groom's family members are received by a reception committee made up of members of the bride's family with their own drummers on the edge of the village or at another prominent point in the village and all guests now go together to the bride's house, where the essential ceremony takes place. The encounter, i.e. the bringing together of the respective music groups, is an essential event in which the two dhol-damau players line up closely and perform a kind of quick rhythmic duel.

During the ceremony at the bride's house, there is always dancing to the accompaniment of the drums. Later or the next day, the bride and groom are led in their respective sedan chairs with a procession to the groom's village. It is often on this occasion that the bride meets the female members of her new family for the first time who did not take part in the brat procession. When the bride returns to her home village after some rituals and usually after two days in a smaller group, she is received there again by drummers and with a religious ceremony ( puja , performed by the pujari ).

In one of the cases described, in addition to the traditional ensembles with dhol-damau and two mashak , a wedding party hired a brass band, which is unusual in a village setting, and which preceded the brat procession. Of the two small drums in this band, one was played roughly with the technique of the dhol and the other like a damau . Although the brass band at and in the bride's house initially took on the musical leadership role and, in addition to the overall background noise, the recitations of the pujari and music recordings from a cassette recorder were added at times, the dhol-damau groups were still at this wedding for the course of the entire ceremony of greater importance.

The dhol-damau pair of instruments is auspicious, structures the process and entertains the guests of the wedding ceremony. In contrast to the Pandavalila, no states of possession are induced for these purposes . The brat procession, which announces their arrival in the bride's village with drum beats, has a symbolic relationship with marching military bands. This association is reinforced by the bagpipe mashak , which was brought to India by military musicians from the Scottish Highland Regiment around the mid-18th century. While the soldiers advance into enemy territory, the groom's wedding party crosses the border of their “safe” home village and the couple to be married is at the transition into a new stage of life.

literature

- Andrew Alter: Controlling Time in Epic Performances: An Examination of Mahābhārata Performance in the Central Himalayas and Indonesia. In: Ethnomusicology Forum, Vol. 20, No. 1 ( 20th Celebratory Edition ) April 2011, pp. 57-78

- Andrew Alter: Dancing with Devtās: Drums, Power and Possession in the Music of Garhwal, North India. (2008) Routledge, Abingdon / New York 2016

- Anoop Chandola: Folk Drumming in the Himalayas. A Linguistic Approach to Music . AMS Press, New York 1977

Web links

- Garhwali dhol damau . Youtube video

- Dhol Damau - Garhwali Dhol Damau Dance - Uttrakhandi Dhol Damau Culture Traditional Dance Part. 2 . Youtube video (singer with dhol and damau at a village festival)

- Pandav leela vill-Nari, rudraprayag uttrakhand. Youtube video ( Pandavalila in a village in the Rudraprayag district. You can see the labyrinth made of strips of fabric for the Chakravyu performance.)

- Latest गढ़वाली शादी। बहुत ही सुन्दर बारात प्रस्थान और डांस दृश्य। रिंकू (गब्बा) की शादी। उत्तराखंड Youtube video (wedding ceremony: gathering in front of a house, then procession on a path)

Individual evidence

- ↑ P. Sambamurthy: A Dictionary of South Indian Music and Musicians. Volume I (A-F). (1952) The Indian Music Publishing House, Madras 1984, p. 127

- ^ Folk Music Instruments of Kashmir (Tumbak). Youtube video

- ↑ Walter Kaufmann : Old India. Music history in pictures. Volume 2. Ancient Music . Delivery 8. Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1981, pp. 31f, 136, 138

- ↑ Bigamudre Chaitanya Deva: Musical Instruments of India. Their History and Development. KLM Private Limited, Calcutta 1978, p. 79

- ^ Curt Sachs : The musical instruments of India and Indonesia. (2nd edition 1923) Georg Olms, Hildesheim 1983, p. 58f

- ^ Henry George Farmer : Reciprocal Influences in Music 'twixt the Far and Middle East. In: The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, No. 2, April 1934, pp. 327–342, here p. 337

- ↑ See Arthur Henry Fox Strangways: The Music of Hindostan. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1914, plate 6 on p. 77

- ^ Reis Flora: Styles of the Śahnāī in Recent Decades: From naubat to gāyakī ang. In: Yearbook for Traditional Music , Vol. 27, 1995, pp. 52-75, here p. 56

- ↑ RAM Charndrakausika: Naubat of Ajmer . Saxinian Folkways

- ↑ Alastair Dick: Nagara . In: Grove Music Online , 2001

- ↑ Nazir A. Jairazbhoy: A Preliminary Survey of the oboe in India . In: Ethnomusicology, Vol. 14, No. 3, September 1970, pp. 375-388, here p. 377

- ↑ Mandira Nanda: Damami. In: KS Singh (ed.): People of India: Rajasthan. Volume 2. Popular Prakashan, Mumbai 1998, p. 292

- ↑ Andrew Alter, 2016, pp. 63f

- ↑ Alain Daniélou, 1978, p. 88: 25 centimeters; Andrew Alter, 2016, p. 63: 30 centimeters; Anoop Chandola, 1977, p. 30: 34 centimeters

- ↑ Anoop Chandola, 1977, pp. 30f

- ↑ Pooja Sah: Traditional Folk Media Prevalent in the Kumaon Region of Uttarakhand: A Critical Study. (Dissertation) Banaras Hindu University, 2012, p. 165

- ^ Andrew Alter, 2016, p. 63

- ^ Alain Daniélou : South Asia. Indian music and its traditions. Music history in pictures . Volume 1: Ethnic Music . Delivery 1. Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1978, p. 88. Daniélou refers to the field research of Marie Thérèse Dominé-Datta (* around 1922) on the narrative tradition and music in Kumaon since the 1950s.

- ↑ Anoop Chandola, 1977, p. 29f; Andrew Alter, 2016, p. 59

- ↑ Anoop Chandola, 1977, p. 41

- ^ Stefan Fiol: Sacred, Polluted and Anachronous: Deconstructing Liminality among the Baddī of the Central Himalayas . In: Ethnomusicology Forum , Vol. 19, No. 2, November 2010, pp. 137–163, here p. 145

- ↑ Andrew Alter, 2016, pp. 39-42; see. Suchitra Awasthi: The Jaagars of Uttarakhand: Beliefs, Rituals, and Practices. In: St. Theresa Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, Vol. 4 No. 1, January – June 2018, pp. 74–83

- ^ Alain Daniélou: South Asia. Indian music and its traditions. Music history in pictures . Volume 1: Ethnic Music . Delivery 1. Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1978, p. 48

- ↑ Andrew Alter, 2016, pp. 49f

- ↑ Andrew Alter, 2016, pp. 51f

- ^ Andrew Alter, 2016, pp. 83f, 86, 90

- ↑ Andrew Alter, 2016, p. 96

- ↑ Bhawna Kimothi, LM Joshi: The Oracle tradition of Pandavalila of Garhwal . In: Himalayan Journal of Social Sciences & Humanities, Vol. 11, 2016, pp. 1–6, here p. 5

- ^ Andrew Alter, 2011, p. 60

- ↑ Andrew Alter, 2016, pp. 107-110

- ↑ Andrew Alter, 2016, pp. 101, 119

- ↑ Andrew Alter: Garhwali Bagpipes: Syncretic Processes in a North Indian Regional Musical Tradition . In: Asian Music , Vol. 29, No. 1, Fall / Winter 1997/1998, pp. 1–16, here p. 3

- ↑ Cf. Gregory D. Booth: Brass Bands: Tradition, Change, and the Mass Media in Indian Wedding Music. In: Ethnomusicology, Vol. 34, No. 2, Spring-Summer 1990, pp. 245-262

- ↑ Andrew Alter, 2016, pp. 155f, 158

- ↑ Andrew Alter, 2016, pp. 137f

- ^ Andrew Alter (2016), pp. 142, 144

- ^ Peter Cooke: Bagpipes in India. In: Interarts , spring 1987, p. 14f

- ↑ Andrew Alter, 2016, pp. 166f