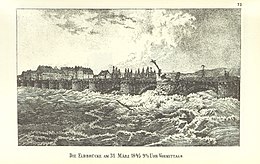

Elbe floods in 1845

The Elbe flood of 1845 in March and April, also known as the Saxon Flood , was an extreme flood of the Elbe that is classified as a flood of the century . Measured by the maximum flow rate, it was the strongest flood of modern times on the Bohemian - Saxon upper reaches of the river. In this respect, it exceeded the Elbe flood in 2002 , but in many places it remained below its maximum water level. This is due to the larger and also still undeveloped retention areas (retention areas) at the time.

A sudden thaw, which resulted in heavy snowmelt in the German low mountain ranges and the rapid breakup of ice on the frozen Elbe, triggered the flood. It is considered to be the strongest winter or spring flood ever measured on the Elbe and the largest Elbe flood of the 19th century. In addition to the Magdalene flood of 1342 and the flood of the century in 2002, the Elbe flood in 1845 was one of the worst natural disasters in Saxony of all time.

course

The winter of 1844/45 was characterized by permanently low temperatures and large amounts of snow. A maximum was reached in February 1845. From February 20, the Elbe was frozen over for several weeks. The thickness of the ice was up to 1.50 meters. On the first Easter holiday, March 23, 1845, the situation changed due to milder air, which, in combination with heavy rain, led to a thaw. The Elbe level rose significantly within a short time. The beginning of the snowmelt in the Giant Mountains , Jizera Mountains , Fichtel Mountains , Bohemian Forest and the Ore Mountains intensified the process. At the Königstein Fortress in Saxon Switzerland the ice broke on March 27, 1845 around 11 a.m., in Dresden further downstream at 7 a.m. one day later. Heavy ice obstructed the drainage and led to large accumulations . The maximum in Dresden was reached on March 31, 1845, and the water level fell significantly and continuously in the first days of April. There were similar incidents during this time on the Main , where, for example, the Würzburg gauge recorded the strongest flood since measurements began.

Floods

Bohemia

In Bohemia, damage occurred in numerous places near the Elbe. Affected were among others Böhmisch Kopist , Deutsch Mlikojed and Kreschitz . Over 70 houses were flooded in Wegstädtl . In Kell , the Elbe rose to 7.26 meters above the normal level, devastated the place and destroyed the harvest. The peak flow of the Vltava , which contributed a large part of the Elbe flood, was 4500 m³ / s at the level in Prague .

Saxon Switzerland

The Elbe breaks through the Elbe Sandstone Mountains in a narrow, canyon-like valley. With large flow rates, there are high water levels due to the scarcely existing floodplains . In Schandau , the river widened from 110 to 250 meters and completely filled the valley floor. In the St. John's Church , the Elbe reached the upper edge of the pulpit parapet. Many buildings in the city center were under water up to the second floor, in Königstein downstream from the Elbe up to the first floor. The old town of Pirna was flooded to 75 percent.

Dresden

In the wide Elbe basin , the Elbe flooded almost 31 square kilometers of what is now Dresden's urban area. Above the city center, this affected the former villages of Zschieren , Meußlitz , Kleinzschachwitz , Pillnitz , Hosterwitz , Laubegast , Tolkewitz and Loschwitz . So far, for the last time, an old Elbarm filled with water along a largely built-up ditch and flowed through the east of the urban area, starting in Dobritz via Seidnitz , Gruna and Striesen to the Pirnaische Vorstadt , where it rejoined the main river. There he flooded, among other things, the Elias cemetery and floated numerous corpses.

The Dresden city center was also affected. Parts of Antonstadt were flooded for the last time in 1845 , including Glacisstrasse, Albertplatz and Alaunstrasse up to Jordanstrasse. On the Old Town side of the Elbe, the Zwinger and large parts of the Wilsdruffer suburb as well as the Friedrichstadt with the Ostragehege were under water.

Large amounts of floating debris and ice accumulated at the Augustus Bridge, so that the water level immediately below the bridge was 85 centimeters lower than above the structure. On March 31, around 10 a.m., the fifth bridge pillar, made of solid Elbe sandstone , gave way to the masses of water and collapsed. On it was a 4.5 meter high, gilded crucifix , which had been made in 1670 under Elector Johann Georg II . The work of art fell into the Elbe and is considered lost.

Large-scale flooding also affected the northwest of today's urban area, where the Elbe leaves Dresden again. Übigau and Kaditz were on larger islands, the wide fields between Mickten and Trachau were completely flooded. Due to backwater, the water from Kaditz reached the Elbe slopes on Wilden Mann and in the east of Trachenberg (area Maxim-Gorki-Straße), which has not been repeated since then. Over the Tiefen Elbstolln which flows into Cotta , the bottom height of which was planned after the Elbe flood of 1784 , the Elbe water penetrated to the Oppelschacht in today's Freital .

Radebeul-Meißen area

Between the village centers of Kötzschenbroda and Cossebaude, the Elbe swelled to a width of two kilometers, only to then split into several arms. A dike broke in Naundorf and the Elbe flooded not only the nearby village center due to backwater, but also the park of Schloss Wackerbarth and the center of Coswig . Since Coswig is deeper, the water there only ran off after a trench had been dug to the Elbe. Today's Coswig districts of Kötitz and Brockwitz were on islands, whereas the Gauernitz Elbe island was completely flooded. The largest island was formed further downstream when the Elbe found its way back into its old bed in Nassau and flowed around the Spaar Mountains on both sides, which has not been observed until the present. At Meißen , among other things at the old town bridge, the ice built up and reduced the outflow. The city was flooded, some houses were up to the roof in the water or collapsed. Several of the Elbe wine villages , which in turn are located in a relatively narrow section of the valley, were also affected.

There are records of this “strangest water” in the Radebeul city archive in the five-volume diary of the winemaker, Bergvoigt der Hoflößnitz and local chronicler Johann Gottlob Mehlig (1809–1870).

Riesa – Torgau area

From Nünchritz , where the Elbe valley becomes somewhat more extensive, the river branched out again. It flowed past Riesa and Strehla with a width of two kilometers. Broken dams caused widespread flooding here, including at Mühlberg / Elbe . As a result, numerous villages that were then part of Prussia were also flooded.

Saxony-Anhalt

Serious damage also occurred in what is now Saxony-Anhalt . The Elbe, which runs here in sections in the cold-time Breslau-Magdeburg-Bremen glacial valley , expanded even further, with great local differences. As a result, however, the intensity of the flood peak was also lost, which is why the flood event of 1845 is less damaging overall further downstream than on the upper reaches. To the north of Magdeburg several dikes broke on the right side of the Elbe, so that the Elbe water flowed eastwards to the four-meter-lower Havel near Rathenow .

Eyewitness reports from Dresden

"The river carried enormous amounts of wood and household appliances, even entire houses."

“The high-pitched, cloudy yellow waves mixed with ice floes licked up to the end of the arches and formed a dizzyingly fast moving, wide and wide roaring surface. The bridge itself was quite deserted and empty, but here and there on the bank, especially on the Brühl terrace, there was an innumerable curious crowd. Gone was the high cross which so often had drawn its beautiful forms on the reddened clouds for me when walking across the bridge in the evening; a gray cloud cover arched over the entire eerie picture, and as I now progressed across the bridge, followed by many thousands of glances, I often thought I felt a shaking of my own under my feet. "

“The torrent of waves pressed its way through the arches of the bridges with terrible force that rafted tree trunks broke like pipe stems on the pillars. The low-lying streets, especially on the Weißeritz, were used by boats, the Fischergasse behind the Brühlsche Terrasse presented itself like a Venetian canal, the pond at the Zwinger stepped over the Ostraallee and connected with the Weißeritzwasser. "

“Since the road sloped off from the Elbe, the water came pretty quickly and we hurried home, the father barricaded the entrance to the yard with horse manure and stones and soon we saw a mighty stream rushing past outside and the water was already pouring in at various points in the garden and yard. Then the father thought of our salvation, because since our property occupied the deepest point, the water had to rise very quickly, which was also the case, because as the father and the good mother each carried two of us through the large garden, they could do it Water up to your knees. [...] How high the water stood could be seen for many years. The stove was softened by the water, collapsed and the soot floating on the surface of the water marked the high level of the water on the house walls. In our not too low rooms, the water almost reached up to the ceiling. On March 31, 1845, the middle pillar of the beautiful Dresden Elbe bridge was torn away by the terrible flood, whereby two bridge arches were devoured by the floods. On the pillar there was a nice, large crucifix, which I had looked at several times before, this was also carried away by the water and, despite long, arduous attempts to find it, it was not possible to save this work of art. The new town was completely separated from the old town by the collapse of the bridge, because the beautiful Augustus Bridge was the only connection between the two parts of the city. Because of the flood, nobody dared to try it on a boat. "

"The din of the houses, rafts and scaffolding shattering against the icebreakers and arched stones, the long wood of which broke like clay pipes, was terrible and filled the inhabitants of the banks of the Elbe with ever greater horror."

consequences

The Saxon Flood provided important findings for flood protection in Dresden and other places near the Elbe. Observations on runoff behavior and the extent of the floodplain were incorporated into the considerations on how such events can be contained. Such a flood was mapped for the first time. The "Map of the Elbe River within the Kingdom of Saxony" was created around 1850. It consists of 15 sections on a scale of 1: 12,000 and contains additional longitudinal profiles. The lithographs go back to A. W. Werner, who colored waters dark and flooded areas light blue (see web links).

From 1861, regulation work began on the entire course of the river. In the process, almost all of the Elbe islands known as "Heeger" disappeared in the Saxon section . The mostly very irregular bank lines were straightened, which increased the current speed and deepened the river bed. This in turn increased the flow capacity and improved navigability. In 1865 the width of the Elbe and the Elbe meadows in Dresden was determined and the area was protected from development. Under the influence of the flood, the surveying inspector Karl Pressler suggested moving the river bed of the Weißeritz to the west in order to make Dresden's Friedrichstadt more flood-proof. As a result, the flood also had an impact on the new construction of the Dresden railway junction and the construction of the Dresden – Děčín (Tetschen-Bodenbach) railway, which runs as an Elbe valley railway about one meter above the apex line observed in 1845.

Also because of the flood, several dyke associations were created in the Magdeburg area , including Rothensee . They initiated the construction of the Elbe flood canal to relieve Magdeburg.

Comparison with 2002

The flood in Dresden in 1845 had a higher flow rate than the Elbe flood in 2002 , but the water level remained somewhat lower. Calculations by the Saxon Hydraulic Engineering Directorate from around 1900, based on observations of the flooded cross-sectional areas and assumptions about the flow velocity, resulted in a discharge of 5700 m³ / s in Dresden on March 31, 1845. This value was later questioned as clearly excessive and refuted. The speed assumptions at that time are considered too high; In addition, the ice accumulation and the enormous water accumulation that occurred at the Dresden gauge on the pillars of the old Augustus Bridge were not sufficiently taken into account. Historical sources give the water level in Dresden at 9.04, 9.30 and even 9.44 meters above today's level zero, which is probably related to the pillar damming. In order to take this effect out of the equation, the authorities subsequently corrected the high to 8.77 meters above today's zero level. For this water level, a discharge of almost 4800 m³ / s is assumed today. The maximum flow of 4680 m³ / s on August 17, 2002, however, resulted in a level of 9.40 meters. The mean flow rate in Dresden is around 320 m³ / s, the mean level at 1.98 meters.

Water levels depend largely on the runoff. The flow velocity and the flow profile influence this variable. The flow profile and thus also the flow velocity have changed in Dresden in the more than one and a half centuries that lie between these two catastrophes, due to the river expansion described in the previous section and the development of floodplains. The development of the retention areas or their separation by dams and dykes restricts the storage volume available to a flood-carrying river. As a result, less water can be stored, the water flows through faster and the flood pours further downstream. In 1845 3093 hectares of today's Dresden city area were under water, in 2002 it was only 2481 hectares.

The storage volume and the flow profile underwent another change in the middle of the 20th century when large amounts of the debris from the air raids on Dresden were dumped on the Elbe meadows. The fact that there was significantly more damage in 2002 than in 1845 is due, among other things, to the increase in the flooded settlement area. In 1845, only 10.5 percent of the flooded area in Dresden was populated; in 2002, 50.1 percent, a significantly higher proportion of settlements in the water.

The level maxima can vary greatly from place to place and depend directly on local flow obstacles, for example bridges, embankments or buildings. In Bad Schandau in Saxon Switzerland, more houses were added to the townscape after 1845, which led to congestion. The water level here exceeded the old record in 2002. On the other side of the Elbe, in the Schandau district of Krippen, the level of 1845 was not reached in 2002, as hardly any noteworthy buildings were added near the bank. While in Riesigk and Schönebeck in Saxony-Anhalt the flood of 1845 still marks the historic high, it was clearly exceeded in 2002 in Roßlau, which lies in between .

A direct comparison between the two events is made difficult by the fact that there are no consistently comparable measured values. When the regular observation and recording of the values on the underside of the crucifix pillar of the Augustus Bridge began in 1776, the zero point corresponded to the water level at which the ships could sail unhindered on the Elbe, which was not yet developed at the time. A writing level went into operation in 1930. On December 1, 1935, the zero point was 105.657 m above sea level. NN by three meters to 102.657 m above sea level. Lowered NN in order to avoid the increasingly frequent negative water levels. According to DHHN12 , this corresponded to 102.736 m above sea level. NN. After switching to DHHN92 , the zero point was 102.68 m above sea level. NHN. If this value is reached, the water level in the fairway is still 65 cm. In addition, since the river expansion began in 1861, the Elbe near Dresden has cut deeper into the river bed due to the higher flow velocity and the associated increased erosion .

Guido N. Poliwoda wrote in the last chapter of his doctoral thesis that disaster management was more efficient in 1845 than in 2002 due to a previous learning genesis.

literature

- Saxon State Office for Environment and Geology (Ed.): Hydrologisches Handbuch. Part 3: Main aquatic values . Dresden 2002.

- Dieter Fügner: Flood disasters in Saxony . Tauchaer Verlag, Leipzig 1995, ISBN 3-910074-31-6 .

- Guido Poliwoda: Learning from disasters. Saxony fighting the floods of the Elbe from 1784 to 1845 . Böhlau, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2007, ISBN 978-3-412-13406-8 .

- Academy of the Saxon State Foundation for Nature and Environment, teaching and research area of landscape planning at the TU Dresden (ed.): Dresdner Planner Talks. Current flood events and their consequences - repair or reorientation towards comprehensive precautions, in particular by means of spatial planning. Dresden 2003. ( PDF ).

- DWA German Association for Water Management, Sewage and Waste e. V. (Ed.): Information for the determination of extreme flood runoff. Hennef 2008. ( Online ).

- Technical University of Dresden, Faculty of Civil Engineering, Institute for Hydraulic Engineering and Technical Hydromechanics (Ed.): Five years after the flood. Flood protection concepts - planning, calculation, implementation. Dresdner Wasserbauliche Mitteilungen, issue 35.Dresden 2007, ISBN 978-3-86005-571-7 . ( PDF ).

Web links

- Map of the Elbe River within the Kingdom of Saxony

- Leibniz Institute for Ecological Spatial Development

- Elbe flood in 1845 ( Memento from April 6, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- "The terrible rush of the water masses" kept people awake

Individual evidence

- ↑ chr-khr.de ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 6.9 MB)

- ^ From Bruno Krause: The historical development of the residential city of Dresden. 1893 @ commons.wikimedia.org

- ↑ coswig.de ( Memento from June 7, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Flood in Radebeul

- ↑ havelland-kiosk.de

- ↑ andreastolz.de ( Memento from October 28, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ welt.de

- ↑ Dietmar Sehn: "Saxon Flood" buries crucifix pillars. Dresden experienced its first flood record 160 years ago. In: Dresdner Latest News . April 4, 2005, p. 7.

- ↑ wilhelm-bergelts-leben.de ( Memento from January 20, 2005 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ segeln-dresden.de ( Memento from September 28, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ DWA German Association for Water Management, Sewage and Waste e. V. (Ed.): Information for the determination of extreme flood runoff. Hennef 2008. ( Online ).

- ↑ dresden.de (PDF; 46 kB)

- ↑ map.ioer.de

- ↑ elbhang-kurier.de ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ uni-protocol.de

- ↑ ioer.de (PDF; 1.0 MB)

- ^ Technical University of Dresden, Faculty of Civil Engineering, Institute for Hydraulic Engineering and Technical Hydromechanics (Ed.): Five years after the flood. Flood protection concepts - planning, calculation, implementation. Dresdner Wasserbauliche Mitteilungen, issue 35.Dresden 2007, ISBN 978-3-86005-571-7 . ( PDF ).

- ^ Academy of the Saxon State Foundation for Nature and Environment, teaching and research area landscape planning of the TU Dresden (ed.): Dresdner Planner Talks. Current flood events and their consequences - repair or reorientation towards comprehensive precautions, in particular by means of spatial planning. Dresden 2003. ( PDF ).

- ↑ Review by Christian Rohr on H-Soz-Kult .de

- ↑ Guido N. Poliwoda: Learning from disasters. Saxony fighting the floods of the Elbe 1784–1845. Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2007. pp. 255–260.