All's well that ends well

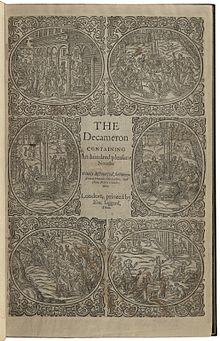

All's Well That Ends Well ( Early Modern English All's Well, Ends Well did ) is a piece of William Shakespeare , which is believed to have originated from 1601 to 1603. As comedy , it can not of the genus uniquely comedy be assigned and is therefore generally regarded as problem-play (Problem pk) or as dark comedy designated (dark comedy). The literary model was provided by a novella from Boccaccio's Decamerone (3rd day, 9th story).

action

Helena, the orphaned daughter of a doctor, is the ward of the Countess of Roussillon (Rossillion) and has fallen madly in love with her son, the young Count Bertram. But the latter does not feel at all attracted to Helena, who on top of that is not noble and therefore his equal. His only aim at the moment is to get to the court of the King of France in Paris to serve as a soldier in Tuscany, and he leaves Roussillon. After his departure, Helena also goes to the king's court in Paris.

There she explains to the terminally ill king that she had a cure from her father by which the king could be cured. After some hesitation, the king agrees to attempt treatment, especially since Helena uses the loss of her honor as a woman as a pledge for failure. However, he orders Helena's death as a punishment if treatment fails. Helena then asks him, as a reward, if she is successful, that she may choose her bridegroom herself from among the king's entourage. In fact, Helena miraculously manages to cure the terminally ill king and she chooses Bertram as her husband. The latter, on the other hand, is initially reluctant to get married on the grounds that Helena is not of his class, but ultimately has to submit to the will of the king and is married to her.

If Bertram could not avoid entering into the marriage, at least he wants to prevent it from being consummated. That is why he secretly leaves the country and goes to war in Italy. In a letter he writes to Helena that he will only recognize her as a wife when she wears his ring (a precious heirloom that he has on his finger) and shows a child whose father he is, i.e. not at all.

Bertram excels in the Florentine military service, while his friend and companion Parolles, a windy braggart, is exposed as a coward and traitor. Helena, who is considered dead in her home country, follows Bertram to Florence and lives in the house of a widow whose daughter Diana is wooed by Bertram, who wants to seduce her and make her his lover.

Helena is now forging a plan together with Diana's mother to meet the conditions of her recognition as a wife: Diana should have Bertram give her his ring in exchange for the promise to meet him in her bedroom at night; there, however, Helena should wait for him instead of her. In fact, Diana receives his ring for the promise that Bertram may come into her room that night. During the nightly get-together, Helena takes on the Stella Dianas as planned and sleeps with Bertram, who does not recognize the deception. As a pledge of love, she gives Bertram a ring that she received from the king in Paris.

When Bertram received the news that Helena had died in a monastery, he returned to France to marry a woman of his own worth. In Roussillon, however, he experiences one surprise after another. The king has him arrested because he has the ring, the royal gift to his healer Helena, in his custody, but cannot satisfactorily explain its origin. Then he is confronted in the presence of the king with Diana, whom he had promised in Florence to marry her after the death of his wife. Finally, Diana's mother and Helena also appear, and she informs him that she now fulfills his conditions for being recognized as a wife: she is wearing his ring and is expecting a child from him. Bertram takes on the role of husband and promises to love Helena from the heart for ever and ever.

Literary templates and cultural references

Shakespeare used the story of Giletta von Narbonne in Giovanni Boccaccio's collection of novels Decamerone (3rd day, 9th story) as a template for the plot . In Boccaccio's story, the miraculous healing of the king and the exchange of bed partners are the essential moments of action. With the motif of the magical healing of the sick king, the cast out wife and the fulfillment of an apparently unsolvable task by a clever girl or the victory of a woman's cunning over the will of men, Boccaccio himself takes up motifs and elements of the oral narrative tradition, which in fairy tales and sagas spread around the world.

Shakespeare knew the story of Giletta von Narbonne either from the English translation of William Painter's The Palace of Pleasure (1566/67) or from the French version of Antoine de Maçon, as suggested by name forms such as Senois. Shakespeare found inspiration for the figure of the healing woman not only in Elizabethan reality, but possibly also in the historical model of Christine de Pizan , whose story was published in 1489 by William Caxton , the first English printer.

The course of action in Shakespeare's play largely follows the template by Boccaccio without major changes, with the exception of the complication and exaggeration of the final section with its sequence of surprising twists. While in the source the main characters, the heroine, the man and the king represent simple fairy tale characters, in Shakespeare's work they are expanded to complex and ambivalent characters. In Boccaccio's Decamerone , Beltramo remains largely innocent; Shakespeare, on the other hand, develops his protagonist into the character study of a young man who becomes increasingly entangled in mistakes and guilt. In Boccaccio's submission, Giletta, as a wealthy heiress, is socially appropriate to Beltramo; as a woman she knows exactly what she is doing. Shakespeare's Helena, on the other hand, is of low origin, as doctors at the time did not have a high social reputation. In the household of the Countess of Roussillon she takes on a more servant-like position, although she is accepted as a foster daughter. In Shakespeare's play, therefore, she shows herself at first full of humility; their ventures are ventures with an uncertain outcome. She subordinates her mind to the feeling of love and on this basis dares the seemingly impossible. Characters like the old Countess of Roussillon, Miles Gloriosus Parolles and the experienced courtier Lafew (Lafeu) and the fool Lavatch, who have no important role in the plot but play a larger role in the dialogues, are new as characters from Shakespeare created.

The motif of the bed-trick , which can already be found in Boccaccio's novella and also used by Shakespeare in Measure for Measure , was not only common in the oral narrative tradition of the time and the Italian short story literature, but also had its forerunners in the Old Testament ( Genesis 38 ) as well as in the Amphitruo by the Roman poet Plautus .

Interpretation aspects

For a comedy almost genre-violating, All's Well That Ends Well is overshadowed for a long time by the motif of death. At the beginning of the actual plot, Helena and Bertram's fathers have just passed away; Bertram's trip to the king's court feels like his mother has lost a second husband. For the characters involved, the end of the drama is overshadowed by the supposed death of Helena, as only the audience knows that she is still alive. With this theme of death, Shakespeare makes the end well, all well, obviously into a dark comedy .

The plot of the play seems to consist of two parts: The miraculous healing of the king is followed by the fulfillment of the apparently unsolvable task set by Bertram. Shakespeare ensures the unity of the plot by the fact that Helena is in love with Bertram right from the start and moves not only to Paris to heal the king, but also to be near Bertram. At first she cannot be sure that the king will give her the opportunity to choose a spouse of her choice as reward for his successful treatment. Shakespeare uses the inversion of an old fairy tale motif.

After Bertram's choice as spouse, Helena remains the driving force, while Bertram's role is reactively limited to rejection and flight. In this respect, the dramatic events, in contrast to earlier Shakespeare comedies, can be viewed as one-strand. The subplot of unmasking Parolles is also done by the officers expressly for the purpose of educating Bertram about the true character of his companion. The accompanying illustration of the main plot, which is usual in other Shakespeare's comedies, by sub-plots or parallel plots is adopted here by commentator characters such as the King, Lafeu or the Countess of Roussillon.

In order not to expose Helena to the accusation of “husband-hunting” due to her dominant position as a heroine , she is not only portrayed as courageous and full of initiative, but also characterized as modest, humble or respectful and willing to learn. Although the Countess of Roussillon wants to adopt her as a daughter at the beginning of the play and would thus remove the class difference, Helena is nevertheless aware from the beginning that, despite her love for Bertram, her low origin represents an obstacle to marriage.

She treats the king without asking for a reward in advance, and even uses her own life and honor as a woman as a pledge for possible failure. Due to the seriousness and severity of the suffering that Shakespeare intensified in relation to his original, the miraculous healing of the terminally ill king is seen by all involved as the work of heaven. This means that Helena has not only royal permission, but also divine approval, to choose her husband.

When Bertram is unwilling to accept her as his wife and goes to war in Italy so as not to have to live with her, she is immediately ready to give up and goes on a longer pilgrimage. In this way she wants to enable him to return from the danger of war. Despite the consent of the King, Lafeus, the Countess and others, a remnant of unease remains on the part of the audience, especially among those with patriarchal values.

Shakespeare's disposition of the figure of Helena is ambivalent: She behaves at the same time active and passive, demanding and humble, determined and obediently waiting. Her early speculative consideration in conversation with Parolles about how it is possible for her to “lose [her virginity] to her own liking” is also striking , I, i , 140).

The seemingly impossible conditions that Bertram sets for accepting Helena as a wife can only be met using the bed trick . The solution, the secret night swap with Diana, with whom Bertram wants to sleep, is known in the literature as the "clever wench" motif, but in Shakespeare's play it cannot simply be interpreted negatively against Helena, as her husband provoked this behavior himself . In addition, she is legally married to Bertram and therefore does not commit any sin; instead, through this exchange, she prevents her husband from committing adultery.

It is true that Helena threads this bed-trick herself, without a male authorization for the intrigue, as is the case with Isabella in Measure for Measure ; However, her plan is at least thought to be morally unobjectionable by Diana, who is being wooed by Bertram, and her mother. Helena also suffers from the fact that Bertram only makes "sweet use" of her spurned body because he confuses her with another lover. Regardless of this, in this way she is able to resolve the conflict in her favor.

Bertram's character drawing has similar problems. On the one hand, the dramatic events unmistakably put him in the wrong, on the other hand, at least for contemporary recipients as a bad person, he would not be an appropriate partner for Helena as a heroine. Introduced as a young man from a good family, the French king expects a lot from him. However, he does not want to be forced into a marriage by the king against his will, even though he is his ward. His behavior is understandable insofar as in times of arranged marriages in the nobility, free consent , that is, consent based on free will, was one of the basic requirements for a legally valid marriage. In Elizabethan England, for example, a marriage ordered by the monarch could be rejected by the ward for reasons of class. Shakespeare prevents this obvious possibility of a refusal of marriage in his play by the offer of the king to give Helena an appropriate trousseau and to raise her to the nobility.

Nevertheless, Bertram's refusal to be suddenly married to a woman he was not involved in choosing himself remains somewhat understandable. With his secret escape from the royal court in Paris, he put himself to a test as a soldier, which he passed so successfully that he was given command of the Florentine cavalry. Bertram now wants to extend his victory on the battlefield by triumphing in love. For this reason he makes advances to Diana, whereby he does not have any illusions about his sexual motives and speaks explicitly of his "dark desires" . Although he promises to marry Diana in the event of Helena's death, he leaves Florence immediately after the nightly meeting. Bertram therefore only fulfilled his sexual initiation in a very superficial, negative way; his honor in war is matched by his erotic shame.

Bertram's character errors are attributed by various characters in the play to the harmful influence of his companion, Miles Gloriosus Parolles. He is portrayed as a misogynist and an advocate of parole for men in battle; however, as his name ("word maker") indicates, his heroic deeds are limited to mere words. The experienced Lafeu sees through him immediately at court and Bertram's friends arrange for his exposure in Italy to open Bertram's eyes. If Helena shows herself to be a kind of good angel of the hero, Parolles embodies a kind of "vice" (dt. Vice ). Structurally, Parolles has a similar function to Falstaff ; however, he lacks the positive charisma of the anarchic and joie de vivre.

Despite the embarrassment of the boastful and cowardly cynic in the feigned interrogation by the enemy, Bertram is initially unimpressed; he must first be forced step by step to hold the mirror in front of himself. This happens in the court scene before the king, which as such is not included in Shakespeare's literary models and was added by him. Obviously, Shakespeare considered this expansion of his models to be dramaturgically necessary in order to trigger Bertram's self-knowledge in a plausible or understandable way. Nevertheless, the bond to Helena accepted by Bertram is not a happy ending, but rather the beginning of an attempt at reconciliation and a new love relationship.

The numerous episodes of the piece are connected primarily by the recurring theme of honor and value. This theme is brought up extensively by the king in his great speech (II, iii, 121ff.). He and the Countess of Roussillon fulfill the commandment of honor from the beginning; Bertram is predestined for an honorable position by his birth, but has yet to acquire this through his own merits. Parolles fails with his attempt to feign honesty, whereas Helena fulfills the conditions of honor and worth.

In recent interpretations of the play, various references are made to a radical questioning of gender roles in Shakespeare's play, which is suggested primarily by Helena's masculine demeanor. In an extreme reading of the work, Bertram is viewed as a mere sexual object that Helena has chosen for herself for purely physical reasons. Likewise, the figure of the king is seen by some recent interpreters as a warning example of the intervention of a monarch in the realm of the private and the erotic. In a politically oriented interpretation of the piece, on the other hand, the dispute between the French king and Bertram is understood as a reflection of the contemporary English conflict between the traditional aristocracy and the new centralized or, increasingly, absolute kingship. This asserts itself against the nobility by promoting social mobility from the bottom up, but at the same time invoking the traditional legitimation model of divine grace .

Dating and text

The time of origin of All's Well That Ends Well cannot be precisely determined, since the piece did not appear in print during Shakespeare's lifetime and there are no other indications or evidence of a contemporary performance that could be used for dating. Therefore, the approximate period of origin can only be narrowed down on the uncertain basis of a stylistic and structural relationship to other, more easily datable works. Usually the origin is set to the period from 1601 to 1603.

This dating is mainly based on the proximity of the piece in its compressed, mentally charged language to the dramas Measure for Measure and Troilus and Cressida . Likewise, All's Well That Ends Well deals with the subject of honor; In addition, there is also the motif of the bed trick and the figure of a flawed young hero who is convicted in a cleverly staged large court hearing at the end. In Measure for Measure , however, Shakespeare uses these elements in a much more complex form; hence, it is commonly believed that All's Well That Ends Well came into being first.

The only early text edition that has survived is the print in the folio edition from 1623. Despite numerous minor ambiguities, this text is considered reliable as a whole. A draft of Shakespeare's ( foul paper or rough copy ) or a copy of it was probably used as the printing template , as the text shows the inconsistencies in the names of the secondary characters characteristic of the foul papers and the careful editing of the stage instructions typical for a theater manuscript ( prompt book ) is missing .

Reception history and work criticism

To this day, All's Well That Ends Well is one of Shakespeare's most seldom performed works and is repeatedly viewed as a problematic piece by readers, viewers and critics alike, even though it coincided with Shakespeare's great tragedies ( Hamlet , Othello , King Lear and Macbeth ) and is not lacking in dramatic, intellectual or linguistic expressiveness.

After Shakespeare's lifetime, there is evidence that it was not performed again until 1741; In the 18th century the piece was comparatively popular mainly because of the figure of the Parolles, whereas in the 19th century it was only performed seventeen times, twelve of them as a singspiel . Until the middle of the 20th century, the play was largely ignored in the theater scene and literary criticism; occasional productions usually had to be canceled after a few performances.

In German-speaking countries, too, Ende gut, alles gut was one of the less popular and rarely performed works of Shakespeare. The piece was first translated into German by Johann Joachim Eschenburg (1775–1782); then by Johann Heinrich Voß (1818–1829) and Wolf Heinrich Graf Baudissin for the Schlegel - Tieck edition from 1826–1833.

Similar to other works by Shakespeare, All's Well That Ends Well has a plot that is so magical that it hardly appears credible outside the world of theater or literature. The actors in this action, on the other hand, are so problematized and at the same time intellectually complicated that they appear to the audience or readers more as characters from the real world than as fairy tale characters. The tensions that arise between what the characters represent and what happens to them in the course of the plot, such as having to be declared happy at the end in the literary genre of comedy, must therefore be accepted.

If this is normally accepted by the recipient despite occasional criticism of the untrustworthiness of some actions, the reception process works well from the end, everything does not work in the same way. Above all, the recipients here stumbled upon Shakespeare's design of the characters of Bertram and Helena and the way in which he leads them to the happy outcome that the title of the play expressly announces in advance.

The focus of criticism was initially on the character of Bertram, whom Samuel Johnson viewed with antipathy and contempt despite his generally cautious praise for the piece. The majority of Johnson’s current criticism also shares a negative view of this figure, although in the meantime there have been numerous attempts to justify or at least explain Bertram's behavior. Although the historical context is aristocratic performances in the Elizabethan era about honor and stand much more understandable in his behavior; nevertheless, he again and again violates the norms and values that are presented as binding in the play itself.

In contrast, the figure of Helena was initially very popular with the recipients. For example, the romantic poet and critic Samuel Taylor Coleridge called Helena “Shakespeare's loveliest character” and the well-known writer and essayist William Hazlitt saw her as “great sweetness and delicacy” . However, this perception changed during the Victorian era ; now it was criticized that this figure in no way corresponds to the ideals of femininity . Not only was her single-minded pursuit of her own interests criticized when the king was healed, but above all the nightly swapping places with Diana, since Helena not only committed a fraud, but also became sexually active as a woman. Even more modern authors such as Katherine Mansfield have distanced themselves from the image of women represented by Helena and criticized the combination of strict virtue and submission to the rules of a misogynist society on the one hand with cunning or even scheming behavior for their own benefit on the other.

The famous Irish playwright and literary critic George Bernard Shaw , however, valued Shakespeare's play highly and interpreted Helena as an emancipated new woman ( "new woman" ) in Ibsen's sense .

In more recent English and Canadian productions in the 1950s, the farce-like - comic traits of the work were primarily emphasized, while the Royal Shakespeare Company, in their revival of the play in 1989, placed the political and social aspects of the play more in the foreground. With these performances in the second half of the 20th century it became increasingly clear that both the main plot about Bertram and Helena and the scenes with Parolles evidently harbor a far greater dramatic potential than previously assumed.

Since then, there has been a change in the assessment of the drama not only in English-speaking countries. Some of the formerly problematic aspects of the play are now more accepted by viewers and critics; broken figures or negatively drawn protagonists are no longer considered problematic.

In more recent interpretations of the piece in the last few decades, it is pointed out above all that the central themes and subtexts of this work are closer to contemporary reality than those of many other dramas; In particular, aspects of the piece such as the differences in the privileges or duties of men and women, the individual worlds of the two sexes with separate values, or the connections between social class, subjective individual values and social validity or respect are highlighted.

To what extent such a tendency to revalue the play from problem play to great play is actually justified in recent criticism will have to be clarified in future literary studies and literary criticism of the work.

Text output

- English

- Jonathan Bate and Eric Rasmussen (Eds.): William Shakespeare: All's Well That Ends Well . The RSC Shakespeare, MacMillan Publishers, Houndsmills, Basingstoke 2011, ISBN 978-0-230-30092-7 .

- Russell A. Fraser (Ed.): William Shakespeare: All's Well That Ends Well. New Cambridge Shakespeare . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2003, ISBN 978-0-521-53515-1 .

- GK Hunter (Ed.): William Shakespeare: All's Well That Ends Well. Arden Second Series. London 1959, ISBN 978-1-903436-23-3 .

- Susan Snyder (Ed.): William Shakespeare: All's Well That Ends Well. Oxford's World Classics . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2008 (1993), ISBN 978-0-19-953712-9 .

- German

- Christian A. Gertsch (Ed.): William Shakespeare: All's Well That Ends Well. English-German study edition. Stauffenburg Verlag, Tübingen 1988, ISBN 978-3-86057-541-3 .

- Frank Günther (Ed.): William Shakespeare: Ende gut, alles gut / All's Well That Ends Well . Volume 15 of the Complete Edition by William Shakespeare in the new translation by Frank Günther. Ars vivendi Verlag, Cadolzburg, 1st edition 2003, ISBN 978-3-89716-170-2 .

literature

- Hans-Dieter Gelfert : William Shakespeare in his time. CH Beck Verlag, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-65919-5 , pp. 344–346.

- Michael Dobson , Stanley Wells (Eds.): The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, 2nd Edition, Oxford 2015, ISBN 978-0-19-870873-5 , pp. 224-226.

- Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Time, man, work, posterity. 5th, revised and supplemented edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , pp. 442-447.

- Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. Reclam, Ditzingen 2006, ISBN 3-15-017663-8 , 3rd rev. Edition 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , pp. 172–177.

- Stanley Wells, Gary Taylor : William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1987, ISBN 0-393-31667-X .

Web links

- All's Well That Ends Well - English text edition from the Folger Shakespeare Library

- All's Well That Ends Well - English text edition on Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- William Shakespeare: All's well that ends well - German text edition in the translation by Wolf Heinrich Graf Baudissin on Project Gutenberg-DE

- Giovanni Boccaccio: The Decameron; Third day, ninth story - German text edition of the literary original Shakespeare on Zeno.org

Individual evidence

- ↑ Cf. Ina Schabert : Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 443. See also Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. 3rd rev. Edition. Reclam, Ditzingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , p. 174 f. See also Michael Dobson , Stanley Wells : The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, 2001, 2nd rev. Edition 2015, ISBN 978-0-19-870873-5 , p. 224. See also the Introduction by Jonathan Bates in the by Jonathan Bates and Eric Rasmussen ed. Edition of William Shakespeare: All's Well That Ends Well . The RSC Shakespeare, MacMillan Publishers, Houndsmills, Basingstoke 2011, ISBN 978-0-230-30092-7 , p. 19. Cf. also the Introduction in Susan Snyder (ed.): William Shakespeare: All's Well That Ends Well. Oxford's World Classics . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2008 (1993), ISBN 978-0-19-953712-9 , pp. 1-8.

- ↑ See Michael Dobson , Stanley Wells : The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, 2001, 2nd rev. Edition 2015, ISBN 978-0-19-870873-5 , p. 294.

- ↑ Cf. Ina Schabert : Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 443 f.

- ↑ Cf. Ina Schabert : Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 444. See also the Introduction by Jonathan Bates in the by Jonathan Bates and Eric Rasmussen ed. Edition of William Shakespeare: All's Well That Ends Well . The RSC Shakespeare, MacMillan Publishers, Houndsmills, Basingstoke 2011, ISBN 978-0-230-30092-7 , p. 2 and p. 10 ff. Cf. also Cf. also the Introduction in Susan Snyder (ed.): William Shakespeare : All's Well That Ends Well. Oxford's World Classics . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2008 (1993), ISBN 978-0-19-953712-9 , pp. 10 ff.

- ↑ Cf. Ina Schabert : Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 444 f. See also the introduction by Jonathan Bates in that edited by Jonathan Bates and Eric Rasmussen. Edition of William Shakespeare: All's Well That Ends Well . The RSC Shakespeare, MacMillan Publishers, Houndsmills, Basingstoke 2011, ISBN 978-0-230-30092-7 , p. 8. Cf. also the Introduction in Susan Snyder (ed.): William Shakespeare: All's Well That Ends Well. Oxford's World Classics . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2008 (1993), ISBN 978-0-19-953712-9 , pp. 25 ff.

- ↑ Cf. Ina Schabert : Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 445 f. See also the introduction by Jonathan Bates in that edited by Jonathan Bates and Eric Rasmussen. Edition of William Shakespeare: All's Well That Ends Well . The RSC Shakespeare, MacMillan Publishers, Houndsmills, Basingstoke 2011, ISBN 978-0-230-30092-7 , p. 9. Cf. also the Introduction in Susan Snyder (ed.): William Shakespeare: All's Well That Ends Well. Oxford's World Classics . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2008 (1993), ISBN 978-0-19-953712-9 , pp. 17 f. and p. 26 ff. See also Hans-Dieter Gelfert : William Shakespeare in his time. Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-65919-5 , p. 146.

- ↑ Cf. Ina Schabert : Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 446 f. Compare with the social and political interpretations also the Introduction by Jonathan Bates in the by Jonathan Bates and Eric Rasmussen ed. Edition of William Shakespeare: All's Well That Ends Well . The RSC Shakespeare, MacMillan Publishers, Houndsmills, Basingstoke 2011, ISBN 978-0-230-30092-7 , pp. 11 ff.

- ↑ Cf. Ina Schabert : Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 442. See also Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. 3rd rev. Edition. Reclam, Ditzingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , p. 174. See also Michael Dobson , Stanley Wells : The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, 2001, 2nd rev. Edition 2015, ISBN 978-0-19-870873-5 , p. 224. See also the Introduction by Jonathan Bates in the by Jonathan Bates and Eric Rasmussen ed. Edition of William Shakespeare: All's Well That Ends Well . The RSC Shakespeare, MacMillan Publishers, Houndsmills, Basingstoke 2011, ISBN 978-0-230-30092-7 , p. 19.

- ↑ Cf. Ina Schabert : Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 442 f. See also Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. 3rd rev. Edition. Reclam, Ditzingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , p. 175. See also Michael Dobson , Stanley Wells : The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, 2001, 2nd rev. 2015 edition, ISBN 978-0-19-870873-5 , p. 224. See also Stanley Wells, Gary Taylor : William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion. corrected new edition. Oxford 1997, ISBN 0-393-31667-X , p. 492. See also the Introduction by Jonathan Bates in the by Jonathan Bates and Eric Rasmussen ed. Edition of William Shakespeare: All's Well That Ends Well . The RSC Shakespeare, MacMillan Publishers, Houndsmills, Basingstoke 2011, ISBN 978-0-230-30092-7 , pp. 19 f. See also the Introduction in Susan Snyder (Ed.): William Shakespeare: All's Well That Ends Well. Oxford's World Classics . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2008 (1993), ISBN 978-0-19-953712-9 , p. 52 ff.

- ↑ Cf. Ina Schabert : Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 447. See also Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. 3rd rev. Edition. Reclam, Ditzingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , pp. 175-177. See also Michael Dobson , Stanley Wells : The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, 2001, 2nd rev. Edition 2015, ISBN 978-0-19-870873-5 , pp. 225 f. See also the Introduction in Susan Snyder (ed.): William Shakespeare: All's Well That Ends Well. Oxford's World Classics . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2008 (1993), ISBN 978-0-19-953712-9 , pp. 40 ff.

- ↑ Cf. Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. 3rd rev. Edition. Reclam, Ditzingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , pp. 175-177. See also Ina Schabert : Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 447 f. See also Michael Dobson , Stanley Wells : The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, 2001, 2nd rev. Edition 2015, ISBN 978-0-19-870873-5 , pp. 225 f. See also the Introduction in Susan Snyder (ed.): William Shakespeare: All's Well That Ends Well. Oxford's World Classics . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2008 (1993), ISBN 978-0-19-953712-9 , pp. 25-34.

- ↑ Cf. Ina Schabert : Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 447. Cf. also the Introduction by Jonathan Bates in the by Jonathan Bates and Eric Rasmussen ed. Edition of William Shakespeare: All's Well That Ends Well . The RSC Shakespeare, MacMillan Publishers, Houndsmills, Basingstoke 2011, ISBN 978-0-230-30092-7 , pp. 3 and 6 f.

- ↑ Cf. Ina Schabert : Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 447. See also Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. 3rd rev. Edition. Reclam, Ditzingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , p. 177 f. See also Michael Dobson , Stanley Wells : The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, 2001, 2nd rev. Edition 2015, ISBN 978-0-19-870873-5 , p. 226. See also the Introduction by Jonathan Bates in the by Jonathan Bates and Eric Rasmussen ed. Edition of William Shakespeare: All's Well That Ends Well . The RSC Shakespeare, MacMillan Publishers, Houndsmills, Basingstoke 2011, ISBN 978-0-230-30092-7 , p. 9 ff. Cf. also the Introduction in Susan Snyder (ed.): William Shakespeare: All's Well That Ends Well. Oxford's World Classics . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2008 (1993), ISBN 978-0-19-953712-9 , pp. 26-40.