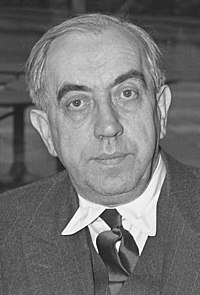

Ernest Reuter

Ernst Rudolf Johannes Reuter (born July 29, 1889 in Apenrade , Schleswig-Holstein Province; died September 29, 1953 in West Berlin ) was a German politician and municipal scientist . Reuter became known as the elected mayor of Berlin at the time the city was split in 1948.

Having grown up in a middle-class environment, Reuter turned to socialism during his studies . From 1912 he belonged to the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and worked for them as an itinerant speaker and journalist . After being taken prisoner by the Russians in World War I , he entered the service of the Bolsheviks after the October Revolution and worked in 1918 as People's Commissar in the settlement area of the Volga Germans in Saratov . From 1919 until his expulsion in 1922 he belonged to the German Communist Party(KPD) on. He held the office of General Secretary of this party from August to December 1921.

Through the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (USPD), Reuter returned to the SPD in 1922, for which he became Berlin City Councilor for Transport in 1926. In 1931 he moved to Magdeburg to become the mayor of that city. After being removed from office by the National Socialists and being imprisoned twice in a concentration camp, Reuter went into exile in Turkey in 1935 .

At the end of 1946, Reuter returned to Berlin and served as city councilor for transport and utilities. In post-war Berlin he quickly developed into the most important social democratic politician. The Soviet occupying power did not recognize his election as mayor by the Berlin city council in June 1947 . During the Berlin blockade , Reuter rose to become the internationally renowned representative of Berlin. After the city split, he held office as governing mayor only in the western sectors . He campaigned for the founding of a West German state and ensured that West Berlin was closely linked to the Federal Republic.

Bourgeois origin and way to socialism

family and school time

Ernst Reuter was the fifth son of Wilhelm Reuter (1838-1926). He already had two sons from his first marriage (one was Otto Sigfrid Reuter ). With his second wife, Karoline Reuter (1851–1941), nee Hagemann, he had four sons, of whom Ernst was the second youngest. Both the father and the mother came from middle -class Protestant families in northern Germany . His father was a teacher at the Royal Prussian Navigation School in Apenrade in 1889. In 1892 he moved to Leer in East Friesland to teach there as head of the helmsman class at the navigation school. Since the Reuters were not among the long-established residents of the small town of Leer, they were respected but largely lived in isolation.

The father's salary was used not only to secure the livelihood but also to build up reserves that were intended for the education of the sons. Family life was characterized by modesty. Father and mother both attached great importance to Christian values , classic humanistic education, patriotism , willingness to perform and fulfillment of duty. One of the interests that Ernst Reuter developed as a schoolboy and youth was a passion for books, especially those by ancient authors. Geography, philosophy and history were also attractive. In addition to these intellectual preferences, there was a tendency to explore nature and landscape. In March 1907 he received his high school diploma in Leer .

Education

In the spring of 1907, Reuter began studying history , German and geography at the Philipps University in Marburg. The neo-Kantians Paul Natorp and, above all, Hermann Cohen were among the professors who influenced him . Reuter was particularly inspired by Kant's code of duties , which complemented the Lutheran heritage of his home. At the same time, the neo-Kantians promoted the high regard for freedom that characterized Reuter throughout his life. In addition to the philosophical insights that these representatives of the Marburg school conveyed to him, another study experience was of lasting importance: A seminar on Bismarck 's thoughts and memories and the background to the Ems dispatch made him develop contempt for the political methods of the long-serving Chancellor , an attitude which brought him into opposition to contemporary Bismarck worship.

From 1907 Reuter was a member of the non-violent student fraternity SBV Frankonia Marburg in the Christian-oriented Schwarzburgbund . For him it was less about the ritualized life of connections and more about opportunities to discuss political and philosophical issues together. Reuter got the reputation of wanting to lead the connection to the left, which led to considerable differences with other members and finally prompted him to change his place of study.

In the spring of 1909 he enrolled at the Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich . One of his Munich teachers was Lujo Brentano , a leading representative of the so-called Chair Socialists , who dealt with the social consequences of the prevailing industrial society in their works . At the same time, Reuter dealt intensively with the history of materialism , a main work of the philosopher Friedrich Albert Lange . Reuter also received other leading protagonists of social reforms, such as the social liberal Friedrich Naumann and the revisionist social democrat Eduard Bernstein .

In Munich , Reuter initially continued his connection life. Here, too, his interests in discussions related to the present met with the reluctance of members of the SBV Herminonia Munich , also a connection that belonged to the Schwarzburgbund. Because of these conflicts, Reuter, together with like-minded people, let his liaison activities rest in the winter semester. He invested the time gained in this way in reading the Socialist Monthly , the theoretical organ of social-democratic revisionism . At the same time he showed a lively interest in the speeches of leading social democratic parliamentarians in the German Reichstag . In addition to his studies and politics, Reuter also used the diverse cultural offerings of the Bavarian metropolis.

When Reuter returned to Marburg in 1910, he had turned socialist . Intensifying internal debates about the admissibility of the social democratic commitment of individual members made Reuter switch to Münster . There he intended to prepare for his state examination. In Munster finally followed the final break with Frankonia, to which he had belonged again in Marburg and Munster. At the same time he met Henriette ("Henny") Meyer, who lived in the same house as Reuter. The couple became engaged on July 15, 1912, after Ernst Reuter had passed his state examination in Marburg in the first few days of July.

Already in the final phase of his studies, Reuter harbored serious doubts as to whether he would be able to reconcile his conscience with teaching in the Prussian civil service. Instead, he thought about ways to become active within the social democratic workers' movement and thus contribute to the implementation of his ideals. Reuter did not tell his parents about his turning to socialism, which was accompanied by an increasing distance from the church.

Social democratic engagement in Bielefeld and Berlin

Reuter joined the SPD in 1912. His parents ended their financial support after he revealed to them that he wanted a career in the labor movement. In the same year, Reuter worked as a private tutor in Bielefeld . At the same time he tried to get a permanent position in the social democratic educational system. At the beginning of 1913, his employer gave notice to him as a private tutor after it became known that Reuter was active in the Bielefeld SPD, including through contributions to the local party newspaper, the Volkswacht . Reuter then made a living by giving lectures to the unions , the party and the workers' teetotalers' association. The father of his fiancé broke off the engagement in August 1913 because of Reuter's political stance, of which he had been informed in a letter by his parents, and because of Reuter's uncertain financial situation. All attempts by the couple to keep in touch were stopped by Henriette's father.

Reuter accepted a one-month job as a social democratic itinerant speaker, which briefly improved his financial situation. In October 1913 he gave lectures in this capacity in the Palatinate on the political significance of the Wars of Independence of 1813 . As early as August 1913 he moved from Bielefeld to Berlin to continue his attempts to establish himself in the socialist labor movement. Through the mediation of Heinrich Pëus , a member of the Reichstag he knew from Bielefeld , Reuter obtained a part-time job with the Non- Confessional Committee , an umbrella organization for the movement to leave the church led by Otto Lehmann-Rußbüldt and Kurt von Tepper-Laski . His hope remained of being able to work for the SPD as a permanent traveling speaker from autumn 1914. In the course of 1914, he was repeatedly active as a speaker and gave lectures on various topics in Berlin, Dresden , Anhalt and Silesia . In the summer of 1914 he completed a lengthy lecture tour in the Ruhr area , speaking under the title From Russian dungeons about the situation of political prisoners in Tsarist Russia .

World War and Imprisonment

Bund new fatherland

The mood described as the “ August experience ” at the beginning of the First World War initially largely silenced many opponents of the political structures of the empire , pacifists and also oppositional social democrats. Advocates of an emphatic military power politics and propagandists of far -reaching annexations initially set the tone. When, after the battles of the Marne and Flanders , the western front became paralyzed in trench warfare, the situation gradually began to change. In November 1914, as a consistent opponent of the war, Ernst Reuter was a co-founder of the Bund Neues Vaterland (BNV). In the early years of the war, the BNV developed into a platform for pacifists of various political persuasions, ranging from a few diplomats to well-known representatives of social democracy. Through pamphlets and memoranda , he tried to work towards a speedy peace agreement, thereby overcoming national-state politics in favor of a European union. Ernst Reuter worked together with Lilli Jannasch as managing director of the BNV and wrote an anonymously published memorandum in early 1915 that criticized German pre-war diplomacy. It was aimed at selected representatives of public life and diplomats. The memorandum aroused overwhelming displeasure in the Foreign Office . Other addressees such as Eduard Bernstein and Richard Witting from the National Bank, on the other hand, sought contact with the BNV. The former German ambassador to London , Karl Max von Lichnowsky , also a harsh critic of pre-war diplomacy, had an hour-long conversation with Reuter because of the memorandum. Reuter did not take part in further discussions between BNV representatives and those interested in the study in March 1915. He had left Berlin on March 22, 1915 to follow his conscription .

war service

The anti-militarist Reuter did not experience his time as a recruit as physical torture. In letters, however, he complained about the harassment to which many of his comrades were subjected by the trainers. Reuter spent vacation days in Berlin. There he informed himself at the BNV about the latest political and military developments, about which the press hardly heard anything. In the spring of 1916, Reuter, who increasingly felt that day-to-day military training was dull, volunteered for the front. From April 1916 he served on the western front and experienced trench warfare and material battles there . At the end of July his troops were transferred to the Eastern Front to repel the Brusilov offensive . On August 10, 1916, he suffered serious wounds - bullet holes and a fractured femur - and was taken prisoner of war by the Russians .

prisoner of war

A transport lasting several weeks took Reuter via Yekaterinoslav , Odessa and Moscow to a military hospital in Nizhny Novgorod . There his wounds slowly healed. From then on, however, he had to rely on a cane to walk throughout his life because his right leg remained short.

Reuter was released from the hospital in November 1916 and sent to the Pereslavl-Zalesski prison camp. Reuter used the convalescence and prison time to learn the Russian language . Soon he was translating the latest news from the Russian press for his fellow prisoners. As these newspapers proclaimed the February Revolution to overthrow the tsar , Reuter's hopes grew for an improvement in the situation in the prison camps and for further sweeping political changes in Russia and beyond across Europe. He saw the increasing influence of the Bolsheviks as a sign that the Russian people were now taking their destiny into their own hands.

Because of his language skills and his political convictions, his fellow prisoners elected Reuter to a commission that was supposed to negotiate prison conditions with the administration. However, these negotiations remained without result, as did a corresponding letter from Reuters to the Provisional Government .

In mid-1917, Reuter was one of those prisoners who, as military personnel no longer able to fight, were to be included in a prisoner exchange. For this reason he was taken to Moscow. However, Reuter himself was not part of the group that was actually able to travel home to Germany via Sweden . Instead, at the end of August 1917, he was sent to a camp near Sawinka, a village in Tula Governorate . There Reuter was used for physical labor in a mine.

Revolutionary on the Volga

Representatives of the prisoners of war

The October Revolution of 1917 also meant a fundamental change in Reuter's living conditions. Reuter welcomed the revolution and hoped to be able to actively contribute to a more just, socialist society. At the same time he was impressed by the will of the Bolsheviks to quickly make peace with the Central Powers .

Reuter, along with two other people, was appointed managing director of the mine where he himself had previously had to work. Reuter quickly took on the responsibility of getting the miners the food and medicine they needed in the increasingly disorganized country. He belonged to a group of three representatives of the local Workers' and Soldiers' Council who traveled to Tula to negotiate with the regional Soviet on the matter. It was here that he first made himself known to the Bolsheviks as a Russian-speaking German social democrat. A little later they brought him to Moscow and in February 1918 appointed him chairman of an international prisoner committee they supported.

In the time leading up to the conclusion of the Peace of Brest-Litovsk in March 1918 , Reuter 's political work among the prisoners of war was aimed at training revolutionaries who were to help implement socialist visions of the future in the event of a political upheaval in Germany. He opposed considerations of using these POWs as resources for a new revolutionary Russian military force, the Red Army .

People's Commissar on the Volga

In April 1918, Reuter left political work with prisoners of war. Lenin , Stalin and other leading Bolsheviks commissioned him to set up an autonomous administration for the German settlers on the Volga , which should be loyal to the new rulers in Moscow. Stalin telegraphed the Soviet authorities in Saratov on the Volga at the end of April 1918 to establish a Volga commissariat for German affairs , paving the way for Reuter.

Reuter's task was to turn the German colonists into loyal citizens of the emerging Soviet state. Socialist school lessons in German should make a special contribution to this. Furthermore, the supply of the big cities, especially Moscow and Petrograd , with grain from this surplus region had to be guaranteed - a fundamental task in times of the Russian Civil War . Finally, one of Reuter's duties was to keep in touch with representatives of Imperial Germany who, on the basis of the Peace Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, looked after German interests in the Volga German region. However, he and his comrades-in-arms were required to prevent these Reich representatives from developing or fomenting any counter-revolutionary activities.

The Volga Commissariat ensured that on June 30, 1918, the first Volga German Soviet Congress met in Saratov. He decided to hold elections for village soviets in the villages of the colonists, which were to tackle socialist land reform. As in the surrounding Russian agricultural areas, conflicts arose in the Volga German villages when Russian revolutionaries requisitioned agricultural products. On July 26, 1918, a government resolution co-signed by Lenin stipulated that all future contributions , confiscations and requisitions would only be permissible with the consent of the German Volga Commissariat.

By the second Volga-German Soviet Congress, held in Seelmann on October 20, 1918, the Volga region had been administratively and politically consolidated under Reuter's leadership. It was considered a model for the establishment of other autonomous regions . This congress - in contrast to the first now dominated by communists and the forces sympathizing with them - expressed their confidence in the commissariat for the work done and elected an executive , which Reuter chaired again. Immediately after the meeting, Reuter left for Moscow on October 24, 1918, to attend the Sixth All-Union Congress of Soviets. He never returned to the Volga because the news of the German November Revolution reached him in Moscow . At the end of 1918 Lenin recommended Reuter Clara Zetkin at the founding party congress of the KPD with the words: "The young Reuter is a brilliant and clear head, but a little too independent."

KPD functionary

Party building in Upper Silesia and Berlin

Together with Karl Radek and Felix Wolf , Reuter crossed the Reich border at Eydtkuhnen in December 1918 on his return journey from Russia . He arrived in Berlin around Christmas and moved into the room he had lived in until 1915. On January 7, 1920, Reuter married Lotte Krappek, the foster daughter of his Berlin landlady. Two children emerged from this marriage, Hella (1920-1983) and Gerd Harry (1921-1992), who became a British citizen in English exile and became a professor of mathematics.

At the turn of the year 1918/19, Reuter took part in the founding congress of the German Communist Party (KPD), but not as a delegate of the Spartacus League , but like Wolf and Radek as a representative of the Russian Soviet power.

His first party task was to build up a powerful communist party apparatus in the Upper Silesia region, which had been destabilized by the uprisings . From March 1919 he began to carry out this task there, using the alias Friesland because open political work by the party was not possible due to the state of siege in the region . This camouflage did not last long, as Reuter was denounced and arrested after just a few weeks. In Beuthen , an extraordinary court- martial sentenced him to three months in prison for holding a political meeting despite the ban. After serving this sentence, he was released in late summer 1919, visited his parents in Aurich and returned to Berlin in October 1919.

His second party assignment made it his task to organize the Berlin section of the KPD. He dedicated himself to this task as Berlin district secretary in the following year and a half. This happened at a time when the young party was suffering severely from bans, internal struggles and also a far-reaching lack of leadership, after the exponents of its founding phase, Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht , had already fallen victim to political murders in January 1919 in the course of the failed January Uprising was. His leading position in the Berlin party apparatus smoothed Reuter's way to the top of the party. At the end of February 1920, the delegates at the third party congress of the KPD elected him as a substitute at party headquarters.

In the course of the Kapp putsch , Reuter spoke out against supporting the general strike, which was intended to force the putschists to give up. The working class should not work to protect the republic. In addition, it is not yet ripe for a revolution and for the establishment of a Soviet republic . From then on, Reuter was counted among the left wing of the KPD. After the left wing of the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (USPD) merged with the KPD in the fall of 1920 and the new party of the Communist International (Comintern) joined, the German communists had the mass base they wanted. Within the party, which initially operated under the name United Communist Party of Germany (VKPD), Reuter became chairman and first secretary of the Berlin-Brandenburg district.

March action, general secretary and break with the communists

Under Reuters leadership, this party district was among the harshest critics of party leader Paul Levi , after he had sought to commit the party to a united front course and a phase of refraining from revolutionary action against the republic. Levi resigned in the wake of these conflicts and the party - under massive pressure from the Comintern - then dared the March Action in March 1921 . However, this attempted uprising in Central Germany was quickly put down. Reuter endorsed the uprising. He continued to defend this revolutionary offensive strategy in the subsequent weeks of passionate internal party controversy. He turned around only after Lenin and Trotsky on the III. World Congress of the Comintern in July 1921 condemned the March Action in the strongest possible terms and called for a period of renunciation of attempted coups and organizational consolidation. Furthermore, Lenin and other leading Bolsheviks had persuaded Reuter in lengthy discussions of the need for a change in German Communist policy. These experiences at the Moscow Congress turned Reuter from a representative of the party left to a spokesman for the party right.

Equipped with the confidence of the Russian party leaders and after an urgent appeal to overcome internal struggles, the delegates at the Jena party congress of the VKPD elected Reuter general secretary of the party in August 1921, Ernst Meyer remained party chairman. Reuter was only able to stay at his post for a short time. Conflicts with the Comintern were already emerging in September 1921, because the latter repeatedly wanted to use appeals, slogans, campaigns and open letters to influence the German communists, although Reuter and with him the newly elected party leadership acknowledged the influence of the Comintern and the Reds Trade Union International (RGI) banned. On November 21, 1921, Wilhelm Pieck and Fritz Heckert attacked Reuter at a board meeting of the VKPD, accusing him of obstructing the Comintern. However, Hugo Eberlein 's application to make Pieck the successor to Reuters in the post of Secretary-General failed.

On November 25, 1921, the Social Democratic party newspaper Forward published documents proving that the VKPD had used provocation strategies before and during the March Action. The party's military-political apparatus, led by Eberlein, had prepared explosive attacks. A munitions factory and a consumer cooperative in Halle were identified as the targets of these attacks. Furthermore, two communist district leaders were to be kidnapped. The provocateurs then wanted to blame the " reaction " for these criminal acts in order to fuel the fighting spirit of the proletariat. The disclosure of this strategy through the revelations in the Vorwarts outraged large sections of the working class.

Reuter was also indignant and repeatedly advocated a relentless internal party investigation into the background and main actors of this strategy. Those responsible for such plans would have to resign. Reuter's demand was at odds with the party leadership, which shied away from open debate and denounced critics such as Levi, who has since been pushed out of the party. Reuters' insistence on criticism and personal consequences would also have resulted in a break with the Comintern, which the majority of the party leadership did not want to risk. Instead, on December 13, 1921, she abolished the office of Secretary General, thereby depriving Reuter of his power. Reuters was expelled from the party on January 23, 1922 , after continuing to mobilize party members and officials to hold those responsible for the March Action to account and to curb Comintern influence. This expulsion from the party ended the so-called Friesland Crisis , into which the party had fallen since December 13, 1921.

Social democratic local politician in Berlin and Magdeburg

Journalist and City Councilman

After being expelled from the VKPD, Reuter initially earned his living by writing articles for the weekly Berlin supplement of the metal workers' newspaper. There was also income from lectures and training courses at trade union events. In April 1922, on the recommendation of the metalworkers ' association, he finally got a job in the editorial office of the Freedom , the central organ of the USPD at the time, which Reuter had joined shortly before. After the majority of the rest of the USPD returned to the SPD in October 1922, he took over the editorship of the forward .

In his journalistic work, Reuter frequently addressed local political issues. He was able to draw on his experience as a member of the Berlin city council , to which he had been elected as a communist functionary in the summer of 1921. In a series of articles, speeches and lectures, he repeatedly demanded reasonable tariffs so that the costs of municipal operations could be covered. At the same time, he demanded more economical management from these companies. Reuter developed a particular interest in questions of inner-city traffic in the rapidly growing metropolis of Berlin. He combined his political work as a representative of the city council in the traffic deputation with his journalistic work.

In addition to articles devoted to local politics, Reuter wrote analyzes of developments in the camp of the communist parties and the situation of the KPD. They were printed not only in the Vorwarts, but also in the magazine Die Glocke , a social-democratic medium edited by Alexander Parvus . Reuter sharply criticized the politics of the KPD in his articles. In 1923 he attested to the communists' worship of military force, in which they would resemble their antipodes on the right side of the political spectrum. A year later he wrote that socialism and communism did not confront each other as hostile brothers, but as completely alien movements.

The crisis year 1923 – marked among other things by the occupation of the Ruhr and the disclosure of the activities of illegal paramilitary formations such as the “ Black Reichswehr ”, communist uprising attempts in central Germany and Hamburg as well as the Hitler putsch and hyperinflation – made Reuter more convinced that a stable democratic state is necessary in order to gradually find the way to socialism on this basis.

Berlin City Councilor for Transport

In the late summer of 1926, the SPD nominated Ernst Reuter for the post of salaried city councilor for transport, and in October of the same year he was unanimously elected. The following spring, Reuter divorced his first wife Lotte. Shortly thereafter he married Hanna Kleinert from Hanover , a politically interested daughter from a social-democratic family who worked as a secretary at Vorwarts . A son was born from Reuters' second marriage in 1928, Edzard Reuter , from 1987 to 1995 Chairman of the Board of Management of Daimler-Benz AG .

Reuter set himself the goal of adapting Berlin's transport system to the requirements of a modern metropolis - with the emergence of Greater Berlin , the capital of the Reich had advanced to become the third largest city in the world. Urban planning and transport policy in Berlin should go hand in hand in order to do justice to the housing and mobility interests of as many residents as possible. Efficient public transport should ensure mobility between the outskirts and the city center. Reuter brought the efforts to municipalize private Berlin transport companies and to integrate the Deutsche Reichsbahn ( S-Bahn ) into a comprehensive system of local public transport to a conclusion. Such a system was considered a prerequisite for uniform and affordable prices. The various modes of transport – tram , bus and subway – were integrated in several steps , until finally on January 1, 1929, the Berliner Verkehrs-AG (BVG) started operations, at that time the largest local public transport company in the world. Reuter took over the post of chairman of the supervisory board of this company.

Reuter was convinced that the future would belong to the automobile . At the same time, as the person responsible for Berlin's transport policy, he pushed for the expansion of the underground system in the city - local public transport should not clog the streets of Berlin, and there must also be an inexpensive alternative to the car that is suitable for mass transport. Before 1914, the subway network had a total length of around 36 kilometers. During the Weimar Republic , that number nearly doubled, with much of this expansion occurring during Reuter's tenure as city councilor for transport. However, Reuter's ambitious plans - the network that existed when he took office was to be expanded by 38 kilometers - failed because the outbreak of the global economic crisis made all the corresponding financial plans a waste. From 1930 onwards, subway construction in Berlin largely stagnated.

Mayor of Magdeburg

Hermann Beims , Mayor of Magdeburg since 1919 , was one of the few Social Democratic mayors in Prussia. When he announced at the end of 1930 that he was retiring from office for reasons of age, the Magdeburg SPD could not agree on a successor from within its own ranks and therefore turned to the SPD party executive. Party leader Otto Wels suggested Reuter. On April 29, 1931, the Magdeburg city council elected Reuter with 38 out of 66 votes as mayor for twelve years.

In Magdeburg, as everywhere in Germany, strong forces of political disintegration became apparent during the years of the world economic crisis. In the days of the mayoral election, the KPD attacked Reuter, whom they held responsible for the mismanagement of Berlin's transport system. The right-wing parties , i.e. the German People's Party (DVP), the German National People's Party (DNVP) and the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP), untruthfully accused him of being responsible for atrocities in the settlement area of the Volga Germans as People's Commissar . This political situation was compounded by a shattered municipal budget: a third of all expenditure had to be used for recipients of support due to the rapidly increasing unemployment in Magdeburg . Like many other cities, the city largely lost its financial sovereignty in 1931, when a Prussian state commissioner was appointed to enforce drastic austerity measures and to reorganize municipal taxes.

Reuter concentrated his work on reorganizing the budget, on continuing infrastructure programs that were intended to stimulate the economy , on promoting self-help projects for the unemployed and on winter emergency aid in the city. Staff cuts in local government and the city council, as well as cuts in unemployment benefits subsequently improved the budget situation. Reuter also pushed through an increase in citizen tax. At the same time, Magdeburg was more energetic than before in collecting property transfer taxes and resident contributions. Reuter also managed to obtain a loan of ten million Swiss francs for the city through the Magdeburger Stadtwerke .

Reuter did not launch extensive infrastructure programs. However, he was anxious to complete those of his predecessor, Beims. These included bridge construction projects, the expansion of the Mittelland Canal , measures to expand the Magdeburg port and the completion of a waterworks in the Colbitz-Letzlinger Heide . Under the direction of Reuters, Magdeburg was also involved in self-help for the unemployed. In outlying districts, the city promoted housing construction by the unemployed. Construction of the first settlement began in May 1932; 50 single-family houses were built in Lemsdorf . By August 1932, construction of four more settlements began.

On September 23, 1931, Reuter invited a number of associations and organizations to City Hall to organize joint winter emergency aid. This welfare program had a surprisingly large success in the winter of 1931/32, so that a large number of needy people could be provided with food, clothing and fuel. Trade unions, employers' associations , welfare institutions , Reichswehr offices and political combat organizations such as the Reichsbanner Schwarz-Rot-Gold and the Stahlhelm took part. Emergency relief continued the following winter.

In 1932, the Magdeburg SPD nominated Reuter as a candidate for the Reichstag , of which he was a member after the Reichstag elections of July 31, 1932 . Even after the November elections of 1932 , he was one of the elected officials. In response to the Prussian strike of July 20, 1932, Reuter, along with Magdeburg police chief Horst W. Baerensprung , considered sending two units of riot police to Berlin to support Republican forces against the putsch. However, this plan did not materialize because the government under Otto Braun gave up without a fight.

imprisonment and exile

persecution and imprisonment

In the Reichstag elections of 5 March 1933 , Reuter defended his Reichstag mandate and also captured a seat in the Provincial Parliament of the Province of Saxony on the same day . Reuter was one of the Social Democratic Reichstag deputies who rejected the Enabling Act on March 23, 1933 . At the first meeting of the provincial parliament of the Prussian province of Saxony on May 30, 1933 in Merseburg, NSDAP deputies beat up the SPD elected representatives. Reuter then had to be treated in the hospital.

SA members stormed Magdeburg City Hall on March 11, 1933 . Among other things, they tried to take Reuter into so-called protective custody . This plan was stopped by a police major who took Reuter into custody and had him taken to the city's police headquarters. Reuter was released there after a few hours and was considered on leave after his removal from the town hall.

On June 8, 1933, Reuter was arrested. The reasons given were anti-state activities as a KPD and SPD functionary and responsibility for atrocities in the Volga region. On July 29, 1933, the National Socialist rulers dismissed him from the services of the city of Magdeburg with reference to the law for the restoration of the professional civil service. On August 11, Reuter was taken to the Lichtenburg concentration camp near Torgau , where he was subjected to severe abuse as a prominent prisoner. Almost five months later, on January 15, 1934, Reuter was unexpectedly dismissed after interventions by foreign authorities and the intercession of Petrus Legge , who knew Reuter from his previous position as provost in Magdeburg.

For two weeks, Reuter recovered from the rigors of imprisonment in Falkenstein im Taunus , where he was a guest in a Quaker home . In 1933, members of this religious community had created sheltered places for the politically persecuted in Germany with the “ Rest Home Project ”. Reuter then contacted other social democrats such as Wilhelm Leuschner and Carl Severing . On June 16, Reuter was arrested again and again sent to the Lichtenburg concentration camp. The prison conditions were more stressful than during the first term. Solitary confinement and, at times, dark confinement were ordered for Reuter . Contact with fellow political prisoners was forbidden, and he was also required to perform menial services. Reuter suffered permanent damage to his health as a result of his imprisonment, including chronic bronchitis and severe hearing damage.

During Reuter's detention, Hanna Reuter mobilized Quakers to work toward his release. Noel Noel-Buxton , a British politician and former minister, eventually wrote to the German ambassador in London asking for an end to the internment. He passed Buxton's request on to the foreign office in Berlin, which in turn asked the Gestapo for a decision. This authority finally decreed that Reuter be dismissed in order not to jeopardize the good relations with Great Britain that he was striving for at the time . Reuter's imprisonment ended on September 19, 1934. The National Socialist authorities then forced the Reuter family to leave Magdeburg, as they feared problems due to his popularity in the city on the Elbe. From the beginning of October 1934, the family lived with Hanna Reuter's mother in Hanover for a few weeks. The Quakers helped again by housing the family in a convalescent home in Bad Pyrmont .

Via Great Britain to Turkey

In January 1935 Ernst Reuter went to England. His family initially stayed in Hanover. Reuter looked for opportunities to find employment in British exile. He lived in Essex with Elizabeth Fox Howard , the Quaker woman who had already helped him in Germany after his first concentration camp imprisonment as manager of the Falkenstein convalescent home and who had used her connections during his second imprisonment to get him released. Reuter also found support from Greta Burkill and her husband, the mathematician John Charles Burkill . The Burkills agreed to take into their care Gerd Harry, Reuter's teenage first son. Reuters search for employment was unsuccessful.

In early 1935 he contacted Fritz Baade , whom the Turkish government had offered to work as an expert on agricultural economics. Reuter also corresponded with Friedrich Dessauer , who had already emigrated to Turkey, and with Philipp Schwartz , who worked in Switzerland, from the emergency association of German scientists abroad . Reuter also turned to Max von der Porten , who was helping to build up the industry in Turkey. At the end of February 1935, Reuter informed von der Porten that he could hope to be employed by the Turkish government. His knowledge of tariffs is interesting. Baade, Dessauer and Schwartz supported these emerging plans. In mid-March 1935 it was decided that Reuters would be employed by the Turkish Ministry of Economic Affairs as an expert in general tariff systems. At the end of May 1935, Reuter finally made his way to Turkey and reached Ankara , his future place of residence , on June 4, 1935 . Edzard and Hanna Reuter followed in September of the same year. Gerd Harry, on the other hand, was looked after by the Burkills. Reuter's daughter Hella, who mostly lived with her mother, stayed in Berlin.

In the service of Turkish ministries

When Reuters took office, the ministry had no documentation on transport tariffs in Turkey. These had to be laboriously procured. Because the Turkish administrative official assigned to him only spoke French and Turkish , Reuter learned the national language.

From 1935 to 1939 Reuter worked in the Ministry of Economics, and then in 1939 in the Ministry of Transport. His tasks included the reorganization of tariffs in the railway sector and the structuring of tariff relations between the railways and coastal shipping . Overall, Reuter was not able to fully develop his potential, because he not only worked in an advisory capacity, but also carried out many administrative tasks himself - he lacked a staff .

Municipal Scientist in Ankara

From 1938 Reuter supplemented his work in the ministry by teaching at the Ankara Administrative College, which was reformed in the 1930s, where he dealt with urban planning and urban development. After 1938, this teaching job took up most of his working time. From 1940 he worked exclusively at the university because all German experts had been dismissed from the Turkish ministries. In 1941 he was appointed professor of municipal science. From 1944 Reuter also worked as a consultant for the shipping and port administration of Istanbul .

Reuter published two Turkish textbooks on urbanism and municipal finance respectively. A third long manuscript in Turkish on local public transport was not published during his exile. He has also published a large number of specialist articles in many of the country's magazines. He also gave speeches and lectures, and a series of specialist analyzes and reports were added.

In his academic work, Reuter dealt primarily with questions of urbanization , housing and building site policy, urban planning, local government and local finance management. In all subject areas, Reuter did not shine through originality or enthusiasm for theory, but showed a pronounced pragmatism . Essentially, he conveyed Western ideas and his own experiences in these questions, which he had made in local politics and administration.

Reuter's pedagogical style had little in common with the country's academic traditions. He asked his students to interrupt him if his Turkish was unclear or if the urbanism terms he used were not correctly translated into the local language. At the same time, he encouraged open discussions, contradiction, independent thinking and the questioning of traditional authorities. This form of imparting knowledge reflected traditions of the Western European Enlightenment .

integration into the exile community

Reuter's circle of friends in Turkey, especially in Ankara, included people who had hardly been involved in politics before 1933. He played skat regularly with the conductor Ernst Praetorius and the Assyriologist Benno Landsberger . Under the direction of the classical philologist Georg Rohde, he read and discussed ancient Greek texts with others. Reuters acquaintances also included the director Carl Ebert , the dermatologist Alfred Marchionini , the administrative lawyer and labor lawyer Oscar Weigert, as well as the architect Bruno Taut and his colleague Martin Wagner , with whom Reuter had traveled in 1929 on a trip to the USA to study the conditions in major American cities to know from your own experience.

Reuter also maintained friendly contacts with Germans who lived in Istanbul, for example with the finance scientist Fritz Neumark , with the social-democratic economics and agricultural specialist Hans Wilbrandt, and with the economists and social scientists Gerhard Kessler and Alexander Rüstow . These contacts with exiles in Istanbul intensified after the start of the Second World War .

The relationship with Fritz Baade, who helped ensure that Reuter came to Turkey, deteriorated. Reuter disapproved that Baade maintained contacts with the German embassy and visited Nazi Germany on several occasions. Baade established these contacts with his work as an agricultural advisor to the Turkish government - almost half of the exports, i.e. mainly agricultural products, went to Germany. Furthermore, Baade stated that during his visits to Germany he tried to establish contacts with the resistance .

While Gerd Harry Reuter stayed in England and turned to mathematics, Reuter's daughter Hella came to Ankara in the spring of 1939 after graduating from high school. The beginning of the Second World War prevented her from returning to Germany, and like her father she stayed in Turkey until 1946.

Politicians on hold

Reuter had had to impose political abstinence on his services to the Turkish government. The predominantly apolitical circle of Reuters acquaintances encouraged this abstinence. In addition, Turkey had chosen far fewer Germans for exile than Great Britain, the USA or Scandinavia . Despite this, Reuter tried to keep up to date with the situation in Germany and Europe. To this end, he followed the coverage of the BBC and the Neue Zürcher Zeitung . He also corresponded with politically active social democratic exiles such as Victor Schiff and Paul Hertz .

After the USA entered the war at the end of 1941 and the German defeats at el Alamein and Stalingrad in 1942/43, Reuter intensified his attempts to influence the future development of Germany from his exile. From the end of 1942 he approached friends and acquaintances in Turkey and abroad with the suggestion of founding a "Movement for a Free Germany". A first important measure of this movement was to win Thomas Mann as spokesman. This project failed, however, because Mann assessed the scope for shaping the exiles as low.

In his correspondence with Mann and others, Reuter protested against collective guilt theses , as expressed above all in statements by the politicians Robert Vansittart and Henry Morgenthau . Reuter countered this with his firm belief in a healthy core of the German people. A politically radically changed post-war Germany has a perspective of equal rights in a united Europe.

Along with Gerhard Kessler, Reuter drove the establishment of the Free German Group in Turkey , later renamed the Deutscher Freiheitsbund . According to the ideas of its initiators, this group should be a cornerstone for a social-democratic anti-Hitler coalition. She produced a series of radio reports, none of which were broadcast because the Allies showed no interest. However, these activities piqued American interest in Reuter. Intelligence officials from the Dogwood network and the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) have been exceptionally positive about Reuters' political leanings and potential.

City Councilor for Transport and Utilities in Berlin

Delayed return to Berlin

When the German defeat was only a matter of time, Reuter felt compelled to return to Germany. In mid-April 1945 he asked the American embassy in Ankara to write a letter of recommendation that would make it easier for him to return home. This request was the first in a series of similar attempts to obtain an official letter allowing for the homecoming. They were all fruitless. It was only when the British got involved and Reuter's efforts were supported by the Social Democrats, who were already active again in post-war Germany, that the situation, which was extremely unsatisfactory for Reuter, changed. On April 29, 1946, Reuter received the message from the British embassy in Ankara that he could enter the British occupation zone and that his route would take him via Paris to Hanover. Reuter's departure was further delayed because the Turkish pound depreciated following a devaluation , driving up travel expenses. He also had to write a memorandum on the Turkish state and municipal bank for the Turkish Ministry of the Interior. On November 4, 1946, Reuters finally embarked in Istanbul and began the journey home via Naples , Marseille and Paris.

magistrate

When Ernst Reuter arrived in Hanover on November 26, 1946 – the place from which Kurt Schumacher reorganized the SPD in the western zones – he still had no clear idea of his future work. He thought it conceivable to go to the Ruhr area and help there, among other things, to reorganize industrial ownership. However, Franz Neumann , one of three equal SPD chairmen in the former Reich capital, asked him on behalf of the Berlin party leadership to become a member of the Berlin magistrate . After initial hesitation and a visit to Berlin, Reuter decided on this offer. On December 5, 1946, the Berlin city council elected Reuter to be city councilor for transport and utilities. Because he was initially unable to find accommodation in the bombed-out city, the magistrate assigned him rooms in the Taberna Academica in Charlottenburg , today the student house of the Technical University of Berlin . The Soviet authorities refused to confirm the new city council. They claimed that he had politically compromised himself in Turkish exile. However, the British and Americans stuck with Reuter.

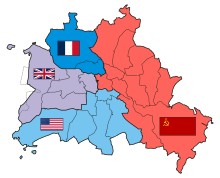

In those days, the four- sector city of Berlin was shaped by the competition between the SPD and the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED), which had emerged as a result of the forced merger of the KPD and SPD in the Soviet occupation zone (SBZ ). The forced union had failed in Berlin and the SPD had achieved a clear victory over the SED in the election to the city council . The struggle for a uniform Germany and Berlin policy of the victorious powers of the Second World War (i.e. the United States, the Soviet Union , Great Britain and France) was added. While the Soviet Union suppressed all attempts to oppose their will, by September 1946 at the latest James F. Byrnes ' speech of hope showed that the Western Allies - especially the USA and Great Britain - increasingly wanted to give the Germans their own creative freedom.

Against this background, one of Reuter's first tasks was to enforce the quotas for the amount of electricity during the so-called hunger winter of 1946/47 , which the Allied command had decided on December 4, 1946 in view of the electricity shortage. Officially, Reuter demanded that the Berliners implement the Allied guidelines, but he later stated that they had implemented these guidelines only slowly . In mid-February 1947, the Allied Command found that their instructions had hardly been heeded and demanded that Mayor Otto Ostrowski punish those responsible. Reuter, who had openly called for Allied policy to be restricted to general guidelines, was thus particularly targeted by the Soviet occupying powers, who demanded that Reuters be dismissed. The French also considered this. However, the Americans and the British protected Reuter and kept him in office.

Mayoral election and Soviet veto

Reuter managed to gain a foothold in the Berlin SPD, which had initially viewed him with skepticism because of his calls for changes in strategy and organization. His self-confident attitude towards the victorious powers contributed significantly to this gain in popularity, and he also developed into a sought-after speaker at party events.

In April 1947, the Berlin SPD voted no confidence in its mayor, Otto Ostrowski , because in February 1947 he had agreed on a work program to alleviate the economic hardship of the Berlin population without internal party consultation with the SED, and with this step he endorsed the clearly anti-communist line of the Berlin SPD seemed to disregard. Reuter was considered a natural candidate to succeed Ostrowski.

The formal objections of the Soviet occupying power to Ostrovsky's resignation showed, however, that they would not be willing to accept Reuter, who was heavily supported by the Americans and who was decidedly anti-Communist. In June 1947 they also managed to ensure that a new mayor of Berlin had to be unanimously approved by the Allied Command . This gave the Soviet side a virtual veto position. Reuter particularly resented the American military governor , Lucius D. Clay , for giving way on this issue. Despite these signs, the SPD nominated Reuter on June 24, 1947 as mayoral candidate. The city council elected him on the same day by 89 votes to 17 with two abstentions.

In the Allied Command, the American and British commanders spoke out in favor of confirmation from Reuters, while the initially reserved French commander raised no objections to confirmation. However, these came from the Soviet commander. Major General Alexander Kotikow stated that Reuter had served in exile with the supposedly pro-Germany Turkish government, and that the German embassy in Ankara, then headed by Franz von Papen , had extended his passport. Finally, the inability of Reuters to be responsible for traffic and utilities has been proven.

The Allied Command referred the issue to the Allied Control Council , the supreme governing body in post-war Germany. He sent the Reuter case back to the commandant's office, which finally informed the Berlin magistrate on August 18, 1947 that Reuters' confirmation was not possible. In Reuter's place, the SPD politician Louise Schroeder managed the business of the mayor, as she had done since Ostrowski's resignation.

Berlin blockade

At the beginning of the Cold War , Germany and Berlin formed a center of global political conflicts. In this situation, Reuter repeatedly emphasized that the former capital of the Reich had to be held by the western powers if further expansion of Moscow-style communism, which he strictly rejected, was to be prevented. As a result, he became more and more a sought-after discussion partner for the representatives of the western powers on all important political and strategic issues affecting the future of the city.

From the beginning of 1948 at the latest, the western powers were working towards the transformation of the bizone into a unified western state. They saw this as an essential prerequisite for the political stabilization of Germany and Europe, which should be promoted with the aid of the Marshall Plan . The USSR, on the other hand, tried to counteract this trend because it feared that it would have significantly less influence on Germany's development and that it would lose access to the western zones' economic resources. In this debate, they viewed Berlin as a crucial lever for asserting their interests.

The final impetus for open conflict came in mid-June 1948 with the introduction of the Deutsche Mark in the western zones and in the western sectors of Berlin. The Soviet Union reacted promptly with the Berlin blockade : on June 24, 1948, it blocked all roads, rail and waterways that led to the western sectors of Berlin, and the power supply was also cut off. Even before this date there had been many obstacles to the movement of people and goods. On June 24, at a large SPD rally in front of an audience of 80,000, Reuter emphasized that the currency dispute was not a question of financial policy, but an expression of the struggle between two opposing economic and political systems. He called on Berliners not to submit to the Soviet claim to power, but to stand up for the city's freedom.

Reuter then made this willingness to resist clear to General Clay, who was impressed by Reuter's firmness and by the will of the Berlin population to accept deprivation. Reuter asked Clay to implement the American plans to supply Berlin from the air. On June 28, 1948, President Harry S. Truman announced the American position: Berlin would be taken care of, the Americans would not withdraw from Berlin under any circumstances. The airlift developed into a lasting success and led to a solidarity of the West German population and the people in the western sectors of Berlin with the Western Allies, especially with the Americans.

Reuter 's popularity and notoriety grew steadily during the months of the Berlin blockade. Through his public speeches he rose to the rank of tribune of the people and internationally symbolized Berlin's desire for freedom. In his speeches, Reuter struck a tone that strengthened the cohesion of Berliners and promoted the anti-communist consensus. With his speeches, he also occasionally managed to put moral pressure on the Western Allies to do what he wanted. The best-known testimony to this is the famous Reuters speech on September 9, 1948 in front of the Reichstag building. In front of around 300,000 people, he used it to appeal to the “people of the world” to look at the city and not give up on Berlin. A good two years later, on September 18, 1950, Reuter appeared on the cover of Time Magazine , which also dedicated the cover story to him.

Advocate for the founding of the West German state

In mid-1948, the West German prime ministers reacted with reservation to the Western Allies' call, laid down in the Frankfurt Documents , to initiate the founding of a West German state. They feared that this Western state would endanger the goal of German unity. Louise Schroeder shared this concern. At the Rittersturz conference on July 8 and 9, 1948, she implored those gathered not to take any irreversible steps until Berlin and the other zones had once again become one. In contrast, at the subsequent Niederwald Conference , Reuter emphasized the provisional nature of a western state to be founded, but on July 20 and 21, 1948 he energetically called for the founding of this state and for Berlin to be included in the process. This vote by Reuters, who represented the ailing Louise Schroeder, contributed significantly to dispelling the concerns of the West German prime ministers. According to this plea, Reuter himself was one of the five representatives of Berlin in the Parliamentary Council , which drafted the Basic Law .

Mayor of Berlin

Election to the Lord Mayor of West Berlin

During the Berlin blockade, Reuter pushed to move the offices of the city administration and the venue of the Berlin City Council from the eastern sector of the city to the western sectors. He prevailed against Ferdinand Friedensburg from the Christian Democratic Union of Germany (CDU), who, as deputy mayor of Berlin, advocated leaving the administrative offices in the eastern part of the city for a long time in order to demonstrate the unity of Berlin and its administration. Reuters contrary position was unintentionally promoted by the obstruction policy of the SED and the Soviet Union, because this approach made effective administrative action for all of Berlin and factual discussions in the city council more and more impossible. At the same time, Reuter advocated the founding of a university in the western sectors that would be protected from the influence of the SED – in November 1948 the Free University of Berlin began teaching in Dahlem . At the beginning of November 1949, Reuter was awarded an honorary doctorate from the Faculty of Economics at this university.

The political division went hand in hand with the administrative division of the city. On November 30, 1948, an extraordinary city council meeting took place in the eastern sector of Berlin, which the deputy city council chairman Ottomar Geschke (SED) had called for. At this meeting, which was dominated by the SED and the mass organizations it directed , those gathered decided to depose the Berlin magistrate. In his place, a “provisional democratic magistrate” was announced and Friedrich Ebert , a son of the first Reich President , was elected Lord Mayor. The representatives of the western military authorities rejected the validity of these resolutions for all of Berlin and limited them to the eastern sector.

A few days later, on December 5, 1948, the population of the western sectors elected a new city council. With 64.5 percent of the votes, the SPD Reuters achieved an outstanding election victory, for which their significant share in the ideological and power-political struggles over Berlin was responsible. On December 7, the city council unanimously elected Reuter mayor. He held this office until his death. Since the introduction of the Berlin Constitution of September 1, 1950 , he has held the title of Governing Mayor of Berlin .

Currency reform in Berlin

After the election for mayor, Reuter pushed for the reactivation of the Allied Command, but from now on as a three-power body. He saw this as a step towards more efficient administration if this went hand in hand with the expansion of German self-government in the western zones. As mayor, he supplemented his domestic political considerations with foreign policy activities. Through visits to London and Paris in 1949, he explored the extent to which it was possible to overcome the monetary policy difficulties – Berlin had had two currencies since the summer of 1948 – and whether the western part of Berlin could become a territory with equal rights in the western state that was to be founded. Despite initial signals to the contrary from the capitals of the Western Allies, Reuters' goal of making Berlin an integral part of the Federal Republic could not be achieved.

However, the implementation of a currency reform was successful: on March 20, 1949, the Deutsche Mark was the sole means of payment in the western sectors. Reuter considered this success an important step towards making West Berlin a symbol of freedom and economic prosperity . According to the magnet theory , the western sectors were to have such an attractive effect on the entire Soviet zone of occupation and, from October 1949, on the German Democratic Republic (GDR) that all parts of Germany would eventually be firmly anchored in the western value and economic system.

economic and financial problems

After the end of the Berlin blockade, the city's serious economic and financial problems became apparent. Only a few, like the five-week Berlin railroad workers' strike in May and June 1949, proved to be temporary. The structural economic and financial imbalances with which the city and its mayor had to struggle were more lasting. In June 1948 the value of industrial production in the western sectors was about 136.5 million DM, at the beginning of the blockade it had fallen to less than 90 million DM. In April 1949, this figure was around DM 73.5 million. The index of industrial production in West Berlin in September 1949 was around 20% compared to the figures for 1936 – the figure for the Federal Republic was higher at the same time than 90%. Unemployment in the western sectors developed in a similarly dramatic manner: almost 47,000 people were unemployed in June 1948, in April 1949 this number was more than 156,000, and in December 1949 it was more than 278,000, which corresponded to an unemployment rate of 24.5%.

Several factors were decisive for the crisis. On the one hand, the Berlin blockade had immensely damaged the city's economic life. On the other hand, the currency reform of March 1949 broke off trade with the hinterland in the Soviet occupation zone. In addition, dismantling , which occurred more frequently in the western sectors of Berlin than in the western zones or the SBZ, caused major problems. After all, after 1945, Berlin lost its role as a financial and banking metropolis and as the most important German administrative location. The falling tax revenues forced the Reuter magistrate to consolidate the budget . At the same time, Reuter did everything to ensure that Berlin was finally included in the Marshall Plan aid, which had been benefiting the western zones since April 1948. In the summer of 1949, Reuter was able to report success on this issue.

Reuter also achieved relief through protracted negotiations with the federal government about permanent Berlin aid. But he had to back off on other issues. When Berlin was declared its capital when the GDR was founded on October 7, 1949, the American Secretary of State Dean Acheson explored whether this violation of the Potsdam Agreement should not be answered by making West Berlin the twelfth federal state of the Federal Republic. Reuter was enthusiastic about this possibility, but Chancellor Konrad Adenauer was strictly against it. With reference to the financial aid from Bonn, which Berlin really needed, and with the threat that the Berlin D-Mark bills, which only had an extra stamp, would no longer be recognized as legal tender, he got Reuter to declare that West Berlin would be included going to the Federal Republic was currently not wise because of the feared international tensions. Reuter then expressed bitterness about the negotiations with the Chancellor.

The tough negotiations finally led in March 1950 to the "First Law on Aid Measures to Promote the Economy of Greater Berlin", which provided tax advantages in particular for companies that placed orders with Berlin companies. Berlin was declared an emergency area in the Federal Republic. The regulations also provided for Berlin companies to be given preference in public contracts if they submitted competitive offers. On June 21, 1950, the Berliner Bank was founded on the initiative of Ernst Reuter. Its primary task was to promote the reconstruction of Berlin's economy.

Legal harmonization between the federal government and Berlin

After many talks and negotiations and with the consent of the Western Allies, who changed the occupation statute accordingly in March 1951 and especially in May 1952, Reuter succeeded in implementing another measure to link West Germany and West Berlin: from now on it was possible for the The Berlin House of Representatives – the successor to the city council since 1950 – decided to extend the scope of West German laws to the western sectors of Berlin in order to ensure legal equality in this way. In 1952, the scope of international treaties and obligations entered into by the Federal Republic were extended to West Berlin.

Relationship to the Berlin and to the federal SPD

Reuter's policy of unconditionally linking West Berlin to the Federal Republic did not go unchallenged in the Berlin SPD. In particular, Franz Neumann and Otto Suhr , head of the city council and president of the House of Representatives, repeatedly acted as leaders of an inner-party opposition to Reuter. They accused him of paying too little attention to the profiling of the Berlin SPD in competition with the other democratic parties. At the same time they claimed that Reuter's policy was endangering achievements in Berlin; the replacement of civil servants by salaried administrative employees, the secular and twelve- class standard school as well as the “classless” standard insurance for all Berlin employees by the Versicherungsanstalt Berlin were important assets of Berlin’s post-war development in the eyes of the opponents within the party. They should promote social reform and tear down bastions of "reaction".

The conflicts on this issue came to a head after the elections to the House of Representatives on December 3, 1950 . The SPD had suffered heavy losses of almost 20 percentage points because they had not made their popular mayor their top candidate, but rather Franz Neumann. At the same time, the SPD's election campaign remained colorless. In the lengthy coalition negotiations, Reuter showed himself willing to compromise when representatives of the CDU and the Free Democratic Party (FDP) demanded changes to civil service law, social security and the school system. Conflicts in the Reuter Senate repeatedly led to Neumann and Suhr calling for an end to the coalition and hoping that going into opposition would strengthen their party. Reuter contradicted these considerations by referring to the threat to Berlin. This makes cross-party government work necessary. At the same time, he warned against perpetuating Berlin's island status by refusing to harmonize the law with the Federal Republic. At the beginning of 1951, he described clinging to the “Berlin achievements” as a fetish. It was not until May 1952 that Reuter finally managed to assert himself against his opponents.

At the federal level, Reuter himself did not agree with Kurt Schumacher's course in Germany. He found his politics to be simplistic and not very flexible. Reuter also did not follow the party leader's instructions in rejecting steps towards common European institutions. For example, he felt that Schumacher's harsh rejection of the Council of Europe was inappropriate.

Before the first Bundestag elections in August 1949 , Reuter was under discussion both as a candidate for Chancellor and as Federal President . However, Kurt Schumacher stood in both votes as SPD representative. Even after Schumacher's death (August 1952), Reuter was considered a possible successor. However, his foreign policy views, which by no means always coincided with those of his party, were a hindrance. He was succeeded instead by Erich Ollenhauer , a man with strong support in the party apparatus.

anti-communism

Reuter never made a secret of his fundamental rejection of communism since he was expelled from the KPD in 1922. His determination to oppose the claim to power and the ideology of communism did not diminish after the end of the Berlin blockade and with the gradual political stabilization in the western sectors of Berlin. Again and again he denounced the lack of freedom of the Soviet system and unequivocally preached the need to set limits to this system. Reuter proved to be a supporter of the then widespread theories of totalitarianism . From 1950 onwards, the Congress for Cultural Freedom represented a forum for Reuters intellectual examination of communism , a movement which – as it later turned out – was influenced by the American secret service CIA . This Congress held its first session in Berlin at the end of June 1950, immediately after the start of the Korean War . Reuter gave the opening speech and was intensively involved in the debates at this congress. On other occasions, Reuter has advocated military deterrence by the Soviet Union and welcomed similar initiatives in Western Europe, while respecting the SPD's traditional skepticism about military policy issues.

Stand up for all-German elections

Reuters' willingness to promote any initiative for free elections throughout Germany or in all of Berlin also resulted from his basic anti-communist attitude. Reuter assumed that the democratic parties would win a clear victory over the communists in such votes.

In the spring of 1950, Reuter therefore supported a corresponding campaign by American authorities for elections throughout Berlin. When Otto Grotewohl presented the proposal for an All- German Constituent Council in November 1950 as a kind of preliminary stage of reunification, Reuter pleaded for an answer, especially since Grotewohl's initiative was supported by the propagation of elections in all of Berlin. Adenauer, on the other hand, saw nothing of substance in these East Berlin initiatives. When Grotewohl again proposed all-German elections in 1951, the federal government called in the United Nations . This formed a commission of inquiry to examine the possibilities of such elections. Reuter led the West German delegation. He addressed the United Nations General Assembly in Paris on this matter and called for elections in Berlin on the basis of the Berlin Electoral Law passed in 1946. However, all plans to prepare and hold all-German elections fell through because the GDR authorities refused to allow UN representatives to enter the GDR.

When in the spring of 1952 the Soviet Union offered reunification in the Stalin Notes at the price of neutralizing Germany, the Governing Mayor of Berlin, along with others such as Jakob Kaiser and Ernst Lemmer (both CDU), finally advocated exploring how serious this proposal actually was . The federal government, on the other hand, stuck to the course of Western integration .

1953: popular uprising, general election, death

The economic and political situation in the GDR led to a growing stream of refugees. After the direct flight to West Germany had been made considerably more difficult in 1952, the way out was via West Berlin. In January 1953, several hundred refugees came to the western part of the city every day, so that Reuter ordered the capacity of the refugee camp to be expanded - instead of 30,000 people, 40,000 people should now be able to be cared for.

With the death of Stalin on March 5, 1953, the political crisis in the GDR came to a head. It seemed unclear which group in the SED leadership would determine the future political fortunes of the country and the economic planning of the east German centrally managed economy .

On June 17, 1953, East Berlin workers who were dissatisfied with the increased labor standards triggered a popular uprising . Reuter was not in town that day, but was on a holiday trip lasting several weeks that had taken him to southern Germany, Italy and Austria . His attempt to fly to Berlin from Vienna failed. He arrived at the scene of the incident the following day. By this time the uprising had already been crushed. All Reuter had to do was to strongly condemn the arrests and executions that had taken place.

In the late summer of 1953, the federal elections had a long-distance effect. This ballot on September 6, 1953 confirmed the ruling coalition under Konrad Adenauer. The economic upswing since the Federal Republic was founded and the chancellor's promise of security were honored by the majority of voters. The SPD, on the other hand, was only moderately convincing at federal level with its strict opposition policy – especially on the question of the new state’s ties to the West. Reuter lamented his party's lack of imagination during the election campaign and called on it to abandon outdated political ideas. However, he left open to his interlocutors where he saw future prospects for the party and whether he would personally contribute to the reform of the SPD as a leading federal or party politician.

On September 28, Reuter canceled his attendance at an evening event because he felt unwell. During the night he suffered a heart attack . On September 29, the 64-year-old fell into a twilight state in the afternoon and died around 7 p.m. After the radio station Reuters reported his sudden death, thousands of Berliners spontaneously put candles in the windows. With this gesture they expressed their attachment to the deceased. At Christmas 1952, he asked Berliners to commemorate those who were still prisoners of war.

A funeral procession and a laying-in in the Schöneberg town hall were followed by a state ceremony on October 3, 1953 . Federal President Theodor Heuss gave the funeral speech, in which he once again underlined Reuter's commitment to a Germany in unity and freedom. Reuter's body was buried in the forest cemetery in Zehlendorf . The grave is one of the honorary graves of the State of Berlin and is located in section 038-485.

aftermath

research history

The life and work of Reuters have been the subject of biographical literature several times in recent decades. For a long time, the study published in 1957 by the two Social Democrats who had remigrated, Willy Brandt and Richard Löwenthal , was considered authoritative. Both identified strongly with Reuters ideals and politics. In 1957, a short summary of the life of Reuters was published, written by Klaus Harpprecht and offering the reader plenty of visual material. In 1965, Hans J. Reichhardt commemorated Reuter with a short biography. Reichhardt and Hans E. Hirschfeld , for many years head of the press and information office in Berlin, published Reuters most important writings, letters and speeches between 1972 and 1975 and provided this four-volume edition with a comprehensive commentary. In 1987, Hannes Schwenger presented a paper that portrayed Reuter less in terms of the structural conditions of the Cold War, and instead placed him in the traditional German lines of protest and resistance. In 2000, the American historian David E. Barclay published a biography that Reuter wanted to bring to the attention of a wide audience and at the same time meet academic standards. This study was supplemented in 2009 by an anthology edited by Heinz Reif and Moritz Feichtinger. The essays published there developed Reuter's work from his local political experiences and his associated ideas about a gradual reform of society. The book presented research results that were presented and discussed at the 2007 conference "Ernst Reuter as Local Politician 1921-1953".

commemoration and remembrance culture

Immediately after Ernst Reuter's unexpected death, there were numerous initiatives in his memory. It was particularly encouraged in West Berlin. For example, as early as October 1, 1953, the authorities ordered a traffic junction to be renamed “ Ernst-Reuter-Platz ”. Since 1954, the Berlin Senate has awarded the Ernst Reuter Plaque to people who have rendered outstanding service to the city . In the same year, the "Ernst Reuter Society of Friends, Sponsors and Alumni of the FUB e. V.” was founded. Every year, this awards Ernst Reuter prizes for outstanding dissertations by members of this university and awards “Ernst Reuter scholarships” for studies abroad. Another prize was the Ernst Reuter Prize for broadcasts , which was awarded until about 1991 . In Berlin there is also an underground station , a high school, a sports field, an administration building , two power plants ( Berlin-Reuter and Reuter West ), the Ernst-Reuter settlement in the Berlin district of Gesundbrunnen , a town hall, a youth hostel and two student residences of the Mayor Reuter Foundation and the passenger ship Ernst Reuter named after Ernst Reuter. In Reuter's former place of residence , Leer (East Friesland) , a new square created in the 1970s at the harbor was named Ernst-Reuter-Platz. Plaques have been placed at other places where Reuters once lived. The Deutsche Bundespost Berlin issued three stamps with his likeness . The radio station RIAS put together an LP for Reuters' 100th birthday ; it contained contributions from the series " Where the shoe pinches us ", founded by Reuter, and other speeches by Reuter.

In September 1959, the American Post Office honored Reuter with two stamps in the “Champion of Liberty” series. There are Ernst Reuter squares, streets and schools in numerous German cities. The German School in Ankara also bears his name. An institute for urban studies at the University of Ankara is named after him. In September 2006, the Foreign Ministers of the Federal Republic of Germany and Turkey, Frank-Walter Steinmeier and Abdullah Gül , launched the Ernst Reuter Initiative for dialogue and understanding between cultures , which is intended to strengthen German-Turkish dialogue.

Despite this culture of remembrance, current articles on Reuter's life and work draw attention to the fact that many Germans only know Reuter vaguely. A recent anthology on Reuter's municipal and socio-political work calls it a research task to determine why Reuter receded so comparatively early in historical memory and finally faded.

writings and literature

Printed works and writings

- Ernst Friesland: On the crisis of our party. Printed in manuscript. Berlin 1921.

- Hans Emil Hirschfeld , Hans J. Reichardt (eds.): Ernst Reuter. Writings - speeches (4 volumes), Propyläen, Frankfurt am Main, Berlin, Vienna 1972-1975.

biographical literature

- David E. Barclay: Look at this city. The unknown Ernst Reuter. Translated by Ilse Utz, Siedler, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-88680-527-1 .

- David E. Barclay: Ernst Reuters activity as Soviet Commissar in the Volga region. In: Reif, Feichtinger (ed.): Ernst Reuter. pp. 69-77.

- Werner Blumenberg : Ernst Reuter. In: Fighters for Freedom. JHW Dietz Nachf., Berlin / Hanover 1959, pp. 172-178.

- Willy Brandt , Richard Lowenthal : Ernst Reuter. A life for freedom. A political biography. Kindler, Munich 1957.

- Klaus Harpprecht : Ernst Reuter. A life for freedom. A biography in pictures and documents. Kindler, Munich 1957.