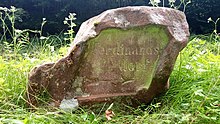

Ferdinandsdorf

Ferdinandsdorf is a deserted area on the boundaries of the Waldbrunn districts of Mülben and Strümpfelbrunn in the Neckar-Odenwald district in Baden-Württemberg . The abandoned place, which was one of the poorest communities in the Grand Duchy of Baden, was on and on the northern slope of the Winterhauchs, a plateau in the southeastern Odenwald , east of the Katzenbuckels . From the Doppelweiler, which was dissolved around 1850 - consisting of Oberferdinandsdorf ( ⊙ ) and Unterferdinandsdorf ( ⊙ ) - there are still numerous remains of the wall, especially on the northern slope of the Winterhauchs, which are part of the "Reisenbachtal" nature reserve . Some cabbage plates can also be identified. Part of the population that remained until then emigrated to America with government support.

history

Origins and development of the clearing settlement Oberferdinandsdorf

Around 1712 Ferdinand Andreas von Wiser , who was pursuing a course of re-Catholicisation on his rule, awarded two clearing areas to four Catholic first-time settlers from Schloßau , Waldauerbach and Hollerbach on a wooded ridge on the territory of his rule in Zwingenberg . After a small clearing settlement had emerged, which was later called Oberferdinandsdorf - to better distinguish it from Unterferdinandsdorf - it initially grew only slowly on the Reisenbacher Grund. Oberferdinandsdorf was not only located on the plateau, but also in parts in the valley and had its own mayor and council. In some sources, the part of Oberferdinandsdorf in the valley is called margravial or Zwingenberg part of Unterferdinandsdorf.

Origins of Unterferdinandsdorf and the merging with Oberferdinandsdorf

From 1780 the court chamber of the Electorate of the Palatinate settled its own "colonists" with a baton holder as head of the valley; This is how the Unterferdinandshof, also known as Unterferdinandshof, came into being, which grew together with the parts of Oberferdinandsdorf in the valley. According to Rüdiger Lenz, the part of the Zwingenberg rulership in the valley grew beyond the border with the approval of the Electoral Palatinate.

Ferdinandsdorf was a branch of the Catholic parish Strümpfelbrunn. Only seven out of 245 residents were Protestant in the 1840s.

The prerequisites for a local development were unfavorable. The place was over 500 m above sea level. NHN comparatively high on the Winterhauch plain and on the associated, sunless northern slope towards the Reisenbacher Grund, where there was only sparse water and, due to a lack of good soil, it was necessary to cultivate marginal yield soils, on which there was also great damage from game. During the first half of the 19th century, the vegetation period on the Winter Hauch was 190-200 days, two weeks below that in the northern Odenwald and even three weeks below that in the Rhine Valley. The location was quite isolated and the transport links poor, which hindered trade and handicrafts. There was no common land in either of the two districts . With the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss Ferdinandsdorf fell to the Principality of Leiningen and 1806 through mediation to the enlarged Grand Duchy of Baden . The princes of Leiningen retained the rulership of Unterferdinandsdorf, Oberferdinandsdorf, always with its parts in the valley, after an interlude by the Göler von Ravensburg , the Electoral Palatinate and the Prince von Bretzenheim to the Counts of Hochberg, who later became the Margraves of Baden .

The class lords never showed any real interest in Ferdinandsdorf. A license for a pub was never granted and a schoolhouse was never built. Since 1770 Ferdinandsdorf had a Catholic teacher who was paid for by the Palatinate clerical administration and later, after the end of the Electoral Palatinate, partly by the Lobenfeld monastery , as the community lacked the financial means for this. However, the lessons and the accommodation of the teacher had to take place alternately in the small houses of the residents. The school was organized as a winter school, which means that lessons only took place when the children's labor was not needed for sowing, harvesting, etc. It was not until 1835, fifteen years before Ferdinandsdorf's end, that the rulers of Zwingenberg acquired a house from a Unterferdinandsdorfer willing to emigrate and left it to the community as a schoolhouse.

Still available statistics on population size are partly contradicting. In the geography and statistics of the Grand Duchy of Baden, according to the latest regulations, the total population of Ferdinandsdorf is estimated to be 245 until March 1, 1820 , in 1831 the handbook for all state authorities in the Grand Duchy of Baden gives 247 inhabitants for the Zwingenberg and 193 for the Liningen part , 1843 in Die Veste Zwingenberg am Neckar - your history and current condition a population of 166 is mentioned. The newest and most thorough alphabetical lexicon of all localities of the German federal states and the political, church and school communities of the Grand Duchy of Baden with the number of souls and citizens of 1845 give 1845 237 inhabitants and the topographical-statistical-historical lexicon of Germany two years before the Resolution 252 inhabitants. Possibly the lineage part was excluded here.

Decline of Ferdinandsdorf

The growing population could hardly be fed due to the small amount of agricultural land. During the war of liberation in 1813, Russian troops were quartered in Ferdinandsdorf. The usual supply of soldiers and their horses at the time, as well as harnessing services, should have burdened Ferdinandsdorf more than the more financially strong communities in the region. From 1816, the year without a summer , the inexorable decline of the settlement accelerated. The community had to be helped out several times with food and seeds. From around 1820 (according to another source from 1819) the two sub-towns of Ober- and Unterferdinandsdorf merged to form the municipality of Ferdinandsdorf. The districts had a common district cadastre, although there were still two districts, they had a common municipal administration, a purchase and deposit book. Apart from a few fire extinguishers, the completely impoverished community had no property and neither had its own forest nor timber rights. The entire community expenditure had to be met from the state treasury.

On November 25, 1841, the municipal councilor Georg Peter Nohe was found seriously injured by his father near the village. A bitter Ferdinandsdorfer who was considered raw and violent had seriously injured Nohe , who was appointed as trustee for his Gant , in the head with an ax. This died on the same day. The incident also received quite a bit of attention in the press in other German states. The perpetrator later confessed that he wanted to fertilize his potatoes with manure, Nohe had opposed this and wanted to sell the manure, which made him angry. A call for donations published in the state press raised 246 guilders 48 kreuzers for the bereaved. Twenty-five guilders of this were set aside for the perpetrator's son, from which the latter would later pay his tuition.

The buildings of the Oberferdinandsdorfer part on the plateau were demolished in 1844 and the land was reforested. The community now consisted only of Unterferdinandsdorf and the parts of Oberferdinandsdorf in the valley that cannot be defined more precisely today.

Unfavorable soils and property that had become too small to feed a family due to the division of inheritance led, driven by climatic conditions, to a food crisis, which in 1845 led to a famine in the Odenwald with the appearance of potato rot. Far below average crop yields caused the prices for potatoes and grain to rise sharply. The debts from the time of the wars of liberation and the centenary sums of many odenwälder communities that have been added since 1831 hardly allowed poor relief. State aid measures took a long time to take hold. The number of beggars wandering around and arrested by the gendarmerie peaked in 1847. These circumstances hit Ferdinandsdorf, which was founded in a remote location and under poor basic conditions, particularly hard. Some Ferdinandsdorfer - who were not yet completely destitute - emigrated to America. Foreclosures increased among the residents who stayed behind.

As early as 1846, a larger group of villagers consisting of seven families with a total of 39 people emigrated to Texas with the help of the Mainz Aristocracy Association .

The Baden Revolution of 1848/49 had little influence on the Ferdinandsdorfer. A former resident who had found a job as a servant in the Grand Duchy of Hesse participated in the damage to the railway in Weinheim. The aim was to block the Main-Neckar Railway in such a way that Prussian intervention troops arriving by train from Frankfurt are prevented from continuing their journey. A Ferdinandsdorfer who served as a soldier in the Baden army participated in the defense of the Prussian intervention troops.

Dissolution of the community, resettlement and emigration

Both the government and the liberal members of the second chamber have always been critical of emigration. Now the view prevailed that long-term support for the impoverished population would be more expensive in the long run than state-financed emigration. Thereupon attempts were made to persuade the population to emigrate. The Baden Estates Assembly approved a bill to dissolve the community of Ferdinandsdorf, and Grand Duke Leopold signed the bill on December 28, 1850. When the administrative act was completed, Ferdinandsdorf was not yet uninhabited. Impoverished citizens unwilling to emigrate were distributed to surrounding towns. This attempt to accommodate the Ferdinandsdorfer in other communities was not easy. No church initially agreed to do so. Those willing to emigrate, around a third of the population, were given state support to emigrate together with Rineckern , whose community was dissolved shortly before Ferdinandsdorf, Tolnaishofern and impoverished residents of other localities. The emigrants were provided with warm coats and, if necessary, with shoes and shirts, stockings and clothes. The year before, this help was not available for the first of the three Rineck emigration groups. The agent of the central office of the Baden emigration association, with whom a contract of carriage was agreed, wrote: Some were barefoot, but most of them were only lightly and very poorly dressed, so that wherever they went to Bremen they caused a stir and regret could only be accommodated in the inns with great difficulty. The journey to emigration began in Eberbach with ships via Mannheim to Cologne, from there by train to Bremen and finally from Bremerhaven with the "Schiller" to New York, where the ship arrived on April 22, 1851. In America every head of the family received 20 guilders and every family member 10 guilders through the consuls. A report from the Mosbach office dated April 30, 1852 about the emigrants from Ferdinandsdorf and Friederichsdorf mentions that the people's letters are all very satisfied. They are in Baltimore, Williamsburg and Albany, their daily wages are 14-18 dollars a month, as craftsmen easily double that. That they are doing well indicates that several of them had sent sums of money of 8-10 guilders to those who stayed behind and not one of them said they would return.

Most of the houses were auctioned off for demolition. However, the secluded location ensured that many remains of the wall still remind of the former settlement. Three houses, including the former Riedsmühle, remained. In 1861 there were 25 adults and nine children under the age of 14 living there. The three properties with their residents were incorporated into Eberbach in 1880. In 1970 the remainder of Ferdinandsdorf was converted to the immediately adjacent, formerly Kurmainzischen Reisenbach near Mudau.

literature

- Robert Bartczak: Bettelmanns Umkehr - decline and dissolution of the hamlet Ferdinandsdorf , in: Der Wartturm - Heimatblätter des Verein Bezirksmuseum e. V. Buchen , edition 1/2000, pp. 2–11, ISSN 0723-7553 This is a short version of Robert Bartczak and Charles Philippe Dijon de Monteton's contribution to the history competition of the Federal President (Germany) 1996/97 Bettelmanns Umkehr: Verfall and decline of the Odenwald settlement Ferdinandsdorf which from poor house to addiction counseling. On the history of helping themed.

- Günther Ebersold: Additions to "Bettelmanns Umkehr - Decline and dissolution of the hamlet Ferdinandsdorf" , in: Der Wartturm - Heimatblätter of the Bezirksmuseum e. V. Buchen , edition 2/2000, pp. 8–9, ISSN 0723-7553

- Rüdiger Lenz: The House of Baden on Zwingenberg - A medieval castle owned by a princely family. ISBN 978-3-89735-912-3

- Rudolf Bleienstein, Friedrich Sauerwein: The deserted Ferdinandsdorf. A contribution to the historical geography of the southeastern Odenwald in: 'Der Odenwald', issue 1978/1 pp. 3–16; Issue 1978/2 pp. 43-56, Issue 1978/3 pp. 99-109, ISSN 0029-8360

- Michael Hahl: Ferdinandsdorf - Amerika !: Fateful story of a desert in the southeast of the Odenwald . Essay. 2008. In: Eberbach: Eberbacher Geschichtsblatt. - 107. 2008. - pp. 75-83, ISSN 0724-4908

- Michael Hahl: Ferdinandsdorf in the focus of environmental historical considerations - A contribution to the discussion of the causes of a modern Odenwald desert , in: The Odenwald - Contributions to the exploration of the Odenwald and its peripheral landscapes , 63rd year - Issue 1/2016, ISSN 0029-8360

- Günther Ebersold: The area of the Neckar-Odenwald district on the eve of the Reichsdeputation Hauptschluss - close-up of the end of an era. ISBN 3-89735-251-6

- Otmar Glaser: The teacher's bedstead stood in a barn in our country home calendar for Neckartal, Odenwald, building land and Kraichgau 2005, pages 245–247, ISSN 0932-8173

- Prof. Dr. Rainer Wirtz: Destabilization of the social order - The Odenwald in the first half of the 19th century in “Der Wartturm - Heimatblätter des Verein Bezirksmuseum e. V. Buchen “Edition 2/1996 Page 9–12 ISSN 0723-7553

- Joachim Schaier: The famine of 1846/47 in the Baden Odenwald. Causes and crisis management in Der Wartturm - Heimatblätter of the Bezirksmuseum e. V. Buchen edition 1/1995, pp. 4–9, ISSN 0723-7553 or more detailed

- Joachim Scheier: Administrative action in a hunger crisis. The famine of 1846/47 in the Odenwald in Baden. Deutscher Universitäts-Verlag, 1991, ISBN 3-8244-4086-5

- Volker Kronemayer: Notes on Emigration in the 19th Century - Problems of Regional and Local Research in Badische Heimat No. 66 (1986) pages 99-109, ISSN 0930-7001

Web links

- Oberferdinandsdorf - Wüstung on the website www.leo-bw.de

- Unterferdinandsdorf - Wüstung on the website www.leo-bw.de

- Emigrants from Ferdinandsdorf on the website www.leo-bw.de

- Sheet 8 “Eberbach” of the topographical atlas of the Grand Duchy of Baden from 1838 on which Ferdinandsdorf is still drawn.

- Announcement of the dissolution of the community Ferdinandsdorf in the "Grossherzoglich-Badisches Regierungsblatt"

- Overview of the emigration in the Grand Duchy of Baden from 1840 to 1855. Published by the Ministry of the Interior

- Description of Ferdinandsdorf in the “attempt at a complete geographical-historical description of the electoral Palatinate on the Rhine. Second part"

- Description of the Amtsvogtei Zwingenberg in the “attempt of a complete geographical-historical description of the electoral Palatinate on the Rhine. Second part"

- Description of the rule of Zwingenberg in "Der Rheinische Bund" - A magazine with historical, political, statistical, geographical content.

- Ferdinandsdorf in the "Universal Lexicon of the Grand Duchy of Baden" Second edition 1847

- Transcription of the passenger list of the “Minna” with three Ferdinandsdorfer latecomers.

Individual evidence

- ↑ GLA 321 No. 382 Changes in the district area and the district boundaries, page / sheet / scan 36, map of the division of the Zwingenberg forest area (1: 25,000, 57 x 97.5 cm, b / w print with color drawings, ed. v. Bad. Topographical Bureau, Karlsruhe, 1923) digitized

- ↑ Ute Fahrbach-Dreher: Evangelical church and rectory in Strümpfelbrunn - a group building from the time of World War I in monument preservation in Baden-Württemberg - news sheet of the State Monuments Office, issue 1/1997 page 29 digitized

- ↑ Rüdiger Lenz: The House of Baden on Zwingenberg, Chapter 10: "Subject and rule - the double settlement Ferdinandsdorf and the margraves" page 91

- ↑ The Grand Duchy of Baden according to its districts, court provinces and administrative districts shown topographically, second increased and revised edition, Müller'sche Buchhandlung 1814, page 82 digitized

- ↑ Rüdiger Lenz: The House of Baden on Zwingenberg, Chapter 10: “Subject and rule - the double settlement Ferdinandsdorf and the margraves”, page 92

- ↑ The Grand Duchy of Baden according to its districts, court provinces and administrative districts shown topographically, second increased and revised edition, Müller'sche Buchhandlung 1814, page 82 digitized

- ↑ Handbook for all grand-ducal Baden state authorities, Karlsruhe 1831, Müller'sche Hofbuchhandlung, page 99 digitized

- ↑ Robert Bartczak: Bettelmanns Umkehr - decline and dissolution of the hamlet Ferdinandsdorf, in: Der Wartturm - Heimatblätter des Verein Bezirksmuseum e. V. Buchen, edition 1/2000, p. 2

- ↑ Rüdiger Lenz: The House of Baden on Zwingenberg, Chapter 10: "Subject and rule - the double settlement Ferdinandsdorf and the margraves" page 91

- ↑ "Universal Lexicon of the Grand Duchy of Baden" Second edition from 1847, page 378 digitized

- ^ "Court and State Manual of the Grand Duchy of Baden" 1841, page 275 digitized

- ↑ Joachim Schaier Administrative action in a hunger crisis - The famine 1846/47 in the Baden Odenwald Wiesbaden 1991, Deutscher Universitäts-Verlag, ISBN 3-8244-4086-5 , page 342

- ^ FJ Baer Chronicle of road construction and road traffic in the Grand Duchy of Baden Verlag Julius Springer, Berlin 1878, page 424 ff. Digitized

- ↑ Robert Bartczak: Bettelmanns Umkehr - decline and dissolution of the hamlet Ferdinandsdorf, in: Der Wartturm - Heimatblätter des Verein Bezirksmuseum e. V. Buchen, edition 1/2000, p. 3

- ^ Negotiations of the Estates Assembly of the Grand Duchy of Baden 1822, 4 volume, p. 10 digitized

- ↑ Günther Ebersold: The area of the Neckar-Odenwald district on the eve of the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss - close-up from the end of an era. Page 39, "The rural nobility": "The Counts of Wiser"

- ↑ imprint of the Electoral between his Highness and those Frey Herrlich Hirschhornischen descendants because of the domination Zwingenberg am Neckar made comparison and concluded Purchase Contracts Digitalisat

- ^ Johann Caspar Bundschuh Geographical Statistical-Topographical Lexicon of Franconia. Description of the immediate freyen imperial knighthood in Franconia after its six locations Verlag der Stettinische Buchhandlung, Ulm 1801, footnote d) page 103 digitized

- ↑ Dr. Ludwig Hauser History of the Rhenish Palatinate according to its political, ecclesiastical and literary circumstances Volume 2 Page 917/918, Heidelberg 1856 Academic publishing house Mohr Digitized

- ↑ Günther Ebersold: The area of the Neckar-Odenwald district on the eve of the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss - close-up from the end of an era. Page 39, "The rural nobility": "The Prince of Bretzenheim"

- ^ The Neckar-Odenwald-Kreis, Landesarchivdirektion Baden-Württemberg in connection with the Neckar-Odenwald-Kreis, Volume II, Thorbecke Verlag, 1992, pages 696, 702, 708

- ↑ Rüdiger Lenz: The House of Baden on Zwingenberg, Chapter 10: "Subject and rule - the double settlement Ferdinandsdorf and the margraves", page 93

- ^ Geography and statistics of the Grand Duchy of Baden, digitized by March 1, 1820 according to the latest regulations

- ↑ Handbook for all state authorities in the Grand-Ducal Baden digitized version

- ↑ The fortress Zwingenberg am Neckar - its history and current condition page 93, Frankfurt am Main 1843 digitized

- ↑ The latest and most thorough alphabetical lexicon of all localities in the German federal states. Digitized

- ↑ The political, church and school communities of the Grand Duchy of Baden with the number of souls and citizens from 1845 digitized

- ↑ Topographical-statistical-historical lexicon of Germany digitized

- ↑ Robert Bartczak: Beggar's reverse - the decline and dissolution of the hamlet Ferdinand village: The watchtower - Heimatblätter the Association District Museum Book e. V. edition 1/2000 page 6

- ↑ Karlsruher Zeitung No. 124 of May 8, 1843, p. 663 ( digitized version )

- ^ Die Land- und Forstwirthschaft des Odenwaldes, Joh. Phil. Ernst Ludwig Jäger, Darmstadt 1843 Verlag Carl Dingeldey, Appendix B. Großherzoglich Badischer Odenwald digitized

- ^ "Ways out of poverty - Baden in the first half of the 19th century" Edited by Rainer Brüning and Peter Exner, Generallandesarchiv Karlsruhe 2007, page 19 digitized

- ↑ “Overview of the emigration in the Grand Duchy of Baden from 1840 to 1855” Published by the Ministry of the Interior, introduction, p. 7. Digitized version

- ↑ Yearbook for Economics and Statistics, edited by Otto Hübner 1857, page 70 digitized

- ^ Supplement to the Karlsruher Zeitung No. 337 of December 8, 1841 ( digitized version )

- ↑ Examples: Passavia - newspaper for Lower Bavaria from December 6, 1841, Nürnberger Allgemeine Zeitung No. 336 December 2, 1841, Bayreuther Zeitung Nro. 288 of December 4, 1841 and in the supplement to the Augsburger Postzeitung No. 343 of December 9, 1841

- ↑ Annals of the Grand Ducal Baden Courts, Volume XXIV No. 27 1857 page 217 digitized

- ↑ z. B. Durlacher Wochenblatt No. 50 of December 16, 1841 ( digital copy , next page )

- ^ Supplement to the Karlsruher Zeitung No. 136 of May 21, 1842 ( digitized version )

- ^ The political, churches and school communities of the Grand Duchy of Baden with the number of citizens from 1845 together with a statistical appendix. Official edition, Karlsruhe 1847, page 86 digitized

- ↑ Mannheimer Abendzeitung from January 19, 1847, cover sheet ( digitized version ) and page 71 ( digitized version )

- ^ Karlsruher Zeitung of October 4, 1845, sheet 3, page 1493 ( digitized version )

- ↑ Joachim Schaier: the famine of 1846-47 in the Baden Odenwald. Causes and crisis management in Der Wartturm - Heimatblätter of the Bezirksmuseum e. V. Buchen Issue 1/1995 pp. 4–9

- ↑ Mannheimer Abendzeitung from September 23, 1846, 1035 "From the state rule Zwingenberg" ( digitized version )

- ↑ Robert Bartczak: Beggar's reverse - the decline and dissolution of the hamlet Ferdinand village: The watchtower - Heimatblätter the Association District Museum Book e. V. edition 1/2000 page 7

- ^ Heinrich Bernhard von Andlaw-Birseck : The revolt and overthrow in Baden, as a natural consequence of the state legislation, with regard to the movement in Baden by JB Bekk, at that time director of the Ministry of the Interior (Freiburg 1850, Herder'sche Verlagbuchhandlung) page 153 , 159 digitized

- ↑ Robert Bartczak: Beggar's reverse - the decline and dissolution of the hamlet Ferdinand village: The watchtower - Heimatblätter the Association District Museum Book e. V. edition 1/2000 page 8

- ↑ Eugen von Philippovich : “The state-supported emigration in the Grand Duchy of Baden” in “Archives for Social Legislation and Statistics - Quarterly journal for researching the social conditions of the states” Berlin 1892, fifth volume, pages 36, 37 digitized

- ↑ Großherzoglich Badisches Regierungsblatt, 49th year, No. I to LXXII, Carlsruhe 1851, No. I, p. 1 digitized version

- ↑ Karlsruher Zeitung of March 1st, 1851, 3rd page ( digitized version )

- ↑ Robert Bartczak: Bettelmanns Umkehr - decline and dissolution of the hamlet Ferdinandsdorf, in: Der Wartturm - Heimatblätter des Verein Bezirksmuseum e. V. Buchen, edition 1/2000, p. 8

- ↑ Eugen von Philippovich: “The state-supported emigration in the Grand Duchy of Baden” in “Archive for Social Legislation and Statistics - Quarterly journal for researching the social conditions of the states” Berlin 1892, fifth volume, page 64 digitized

- ↑ Eugen von Philippovich: “The state-supported emigration in the Grand Duchy of Baden” in “Archives for Social Legislation and Statistics - Quarterly Journal for Researching the Social Conditions of the Countries”, page 52 digital copy

- ^ Karlsruher Zeitung of March 14, 1851 ( digitized version ) and March 16, 1851 ( digitized version )

- ^ Transcription of the "Schiller" online passenger list at immigrantships.net

- ↑ Eugen von Philippovich: "The state-supported emigration in the Grand Duchy of Baden" in "Archives for Social Legislation and Statistics - Quarterly journal for researching the social conditions of the federal states" Berlin 1892, fifth volume, p. 64 digital copy

- ↑ Eugen von Philippovich: “The state-supported emigration in the Grand Duchy of Baden” in “Archives for Social Legislation and Statistics - Quarterly journal for researching the social conditions of the federal states”, page 65 Digital copy

- ^ Neckarbote dated April 11, 1845 ( digitized version )

- ↑ Karlsruher Zeitung of November 20, 1852 ( digitized version )

- ↑ GLA H-1 No. 378, 2, district overview plan Pleutersbach, ... side map with Ferdinandsdorf digitized

- ↑ GLA H-1 No. 512, 1, Friedrichsdorf (City of Eberbach HD) and Zwingenberg place and forest markings digitized

- ^ Grand Ducal Ministry of Commerce: Contributions to the statistics of the internal administration of the Grand Duchy of Baden from 1861, page 60 digitized

- ↑ The Neckar-Odenwald-Kreis, Landesarchivdirektion Baden-Württemberg in connection with the Neckar-Odenwald-Kreis, Volume II, Thorbecke Verlag, 1992, page 702