Women's suffrage in the United States with Puerto Rico

The women's suffrage in the United States and Puerto Rico has had a checkered history. On the federal level, which was in the US active and passive voting rights in the 19th Amendment to the Constitution of the United States through an agreement of the State of Tennessee finalized on August 24, 1920 and became effective on August 26, 1920 into force. In the states of the United States , the introduction of the right to vote for women extended over a long period of time. In New Jerseywealthy women were given the right to vote as early as 1776, but later lost it again. It was not until 1918 that women's suffrage was introduced in all states. In some of them, restrictions such as reading and writing tests and taxes were still used after 1920 to prevent women from voting. A number of factors influenced the fact that women's suffrage became law in all parts of the United States. These include, for example, the work of women's organizations, impulses from the labor movement and the development of women's suffrage in Europe. However, the experience with women as voters from the western states of the USA, who pioneered the introduction, is considered essential. There it became clear that women voted in the same way as their husbands and therefore did not pose a threat to the existing power relations.

In Puerto Rico , a law was passed on April 16, 1929 that gave all women who could read and write the right to vote, but this effectively excluded most Puerto Rican women from voting. It was not until 1935 that universal suffrage was guaranteed.

Investigation of possible influencing factors on the political representation of women

Party cliques and political clusters

Between 1890 and 1910 the blocs of the political parties hardened and the party clique gained more influence. This was against any change in the electoral law, as he feared changes in the elaborate calculation with the political majorities. There are examples of openly manipulative interventions by party leaders: In 1913, women in Illinois were given the right to vote in presidential elections, but not in local elections. It was feared that otherwise women would force their way into politics at the local level and that male political clusters could lose their power, which suggested the demand of the women's suffrage movement for an end to corruption.

Connection with other goals of women

By the turn of the 20th century, women's property rights and educational opportunities had improved. This weakened the women's suffrage movement, which saw the political representation of women as the key to further progress.

Women's organizations

- NAWSA

By the turn of the 20th century, the women's movement had largely lost its vigor. The middle class activists did not want to include the organizing working class and the unions in their struggle. Carrie Chapman Catt campaigned against prejudice in the NAWSA regarding certain ethnicities and classes at the beginning of the 20th century, which led to a change of course and opening up.

In 1913 Anne Martin , Alice Paul and Lucy Burns founded the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage together with fellow campaigners in order to initiate a constitutional amendment at the national level. This group, while still working within NAWSA, came into conflict with the group because of what other members believed to be too radical of views, which led to its expulsion from NAWSA in 1916.

- Equality League of Self-Supporting Women

Harriot Eaton Stanton Blatch , who had lived near London, campaigned for a renewal of the women's suffrage movement on her return to the USA . In 1907 she founded the Equality League of Self-Supporting Women (later renamed the Women's Political Union ) to attract working class women to the suffragist movement. Blatch succeeded in mobilizing women from the working class and at the same time continuing to work with women from the bourgeois equality movement. On the one hand, she organized street protests, on the other hand, she worked with great diplomatic skill to neutralize those who opposed women's suffrage. These were politicians from the Tammany Hall group who feared women would vote for Prohibition .

Common interests with the working class

The historian Alexander Keyssar argued that the convergence of working class interest in women's suffrage with the suffragist interest in working class resulted in the women's suffrage movement becoming a mass movement for the first time from 1910 onwards. In 1915 NAWSA had 100,000 members, by 1917 it had already reached two million. The influence of the labor movement and its forms of protest is seen as essential for the strengthening of the women's suffrage movement.

Race issue

Racial inequality rather than gender inequality was the most prominent feature of the United States in the early 20th century. An essential factor in the calculations of the supporters of the women's suffrage movement, who were also looking for supporters in the southern states, was the maintenance of white supremacy.

In the early twentieth century, the racial divide that was opening up in the women's suffrage movement was particularly noticeable in the southern United States. Black women should not get the right to vote because it was thought that they were more educated than black men, that they were more clear about their rights and therefore more difficult to manipulate. Opponents of the women's suffrage movement proclaimed that women's suffrage would result in black rule. Supporters of the Democratic Party expressed that black women the Republican Party vote and so the Democrats would destroy in the South. On the other hand, it was argued that eligibility criteria such as paying certain taxes or proof of being able to read and write would make it easy to deprive black women of their right to vote, as it had been with black men. The supremacy of whites would be strengthened by women's suffrage.

Racial issues also played a role within women's organizations. At the 1903 NAWSA meeting, racial segregation prevailed. The NAWSA had also - probably with consideration for the southern states - allowed member states to introduce racial barriers in their local member organizations. Black women were allowed at the next meeting. At the big march in front of the White House , white women announced that they would not participate if black women were also there. The NAWSA then determined that black women were allowed to participate, but should march in a separate block at the end of the train.

Developments in Europe

The development of women's suffrage in Europe intensified the movement in the USA: the influence of Great Britain was not only evident in literature, but also in Emmeline Pankhurst's lecture tours in the USA in 1909, 1911 and 1913 and, above all, in the activities of young women who learned how militant women there were while traveling to Britain. One of these travelers, Anne Martin, was arrested there on Black Friday 1910 while on a trip to London and became the driving force behind the women's suffrage movement in Nevada , which saw the introduction of women's suffrage there in 1914. Even Alice Paul and Lucy Burns belong to this group of women.

Richard J. Evans is of the opinion that the values of the American Protestant middle class seemed to be endangered by Germany, but even more so by the Bolsheviks and the revolutions that followed them. The introduction of women's suffrage was one of the measures to strengthen these values.

Experience with women as voters

The low turnout of women in areas where they had been given the right to vote was used as an argument against expanding women's suffrage at the turn of the 20th century. In the United States presidential election in 1916 , the failure of the strategy of Alice Paul, was enfranchised women to mobilize against the Democrats : The women were not based in the voting behavior of the activists, but to their husbands. The advocates of women's suffrage used this phenomenon for their own purposes and saw it as proof that women's suffrage has no influence on the balance of power and that political clans who feared the opposite are in the wrong.

As a major factor in women's suffrage becoming law in all parts of the United States, Adams cites the experience of women voting in the western states that pioneered its adoption. There it became clear that women would vote in the same way as their husbands and therefore do not pose a threat to the existing balance of power.

Merits of women in World War I.

The fact that the last phases of the struggle for women's suffrage coincided with the First World War and its end should not be overestimated, since women's suffrage in general was obtained very often during or shortly after national upheavals. The First World War did not bring about women's suffrage, but it did create a climate conducive to it and gave advocates further arguments .

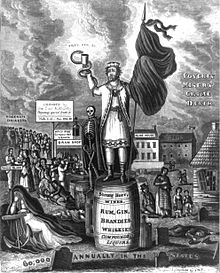

Puritan ethics

Historian Alan Grimes describes how a Puritan ethic gained popularity during the First World War . It affected a number of laws, such as the reading and writing test introduced in 1917 for immigrants, prohibition and the introduction of women's suffrage. These improvements showed the will to improve society and, if necessary, impose rules on it. A number of parallels can be made between the development of the women's suffrage movement and the fight against alcohol: Both gradually achieved success in more and more states; before 1910, the growth of women's suffrage in five southern states coincided with the enactment of laws banning alcohol; between 1914 and 1916 alcohol restrictions were passed in fourteen other states. Prohibition stood for the values of the civilized world: the control of blacks and new immigrants by a white middle class. The advocacy of women's suffrage also became more and more a hallmark of classes that claimed to be civilized. Before the First World War , however, the prohibition movement was more popular than the women's suffrage movement.

Militant approach

While a large part of the success of the women's suffrage movement can be traced back to the patient and determined actions of its advocates, additional influences and actions by militant groups were necessary to prevent the energy from waning. When the United States entered World War I in 1917, members of the National Woman's Party protested against it on the following grounds: The United States fought abroad to make the world safer and more open to democracy, while at home women were denied democratic rights. It is controversial whether this militant approach helped or harmed the cause. Women who had followed the policy of taking small steps were irritated. The NAWSA, however, made more efforts to emphasize its moderate position vis-à-vis the radical ones and thus gain supporters. In any case, the militant approach did not prevent the success of the referendum in New York in 1917.

Financial support

The referendum campaign in the most populous state of New York was unsuccessful in 1915, but successful in 1917 after the publisher Miriam Leslie had given her one million dollars in financial support.

Political calculation

Carrie Catt supported President Wilson after entering World War I, although this went against her pacifist stance. During the national crisis, she offered him the support of her two million women supporters if, in return, he would support women's suffrage. In January 1918, for example, the president was able to announce that he supported the inclusion of women's suffrage in the constitution as a measure in connection with the war. The next day, the United States House of Representatives passed a constitutional amendment to this effect by a majority of one vote. On September 30, 1918, he urged the Senate to approve it on the grounds that the war could not have been waged without the women. In doing so, he countered the argument that women did not deserve the right to vote because they did not do military service. However, the constitutional amendment did not achieve the necessary two-thirds majority.

Development in the states

Local suffrage

Between 1890 and 1910 there was only progress in granting women suffrage at the local level, and again in some areas this was limited to women who had passed a literacy test or paid taxes.

State-level voting rights

At the state level, women's suffrage was achieved at different times.

In New Jersey , wealthy women had had the right to vote since 1776 and began voting in 1787. When universal male suffrage was introduced there, wealthy women also lost the right to vote.

The introduction of universal suffrage in the western United States coincided with the conversion of territories into states . In the years from 1910 the right to vote for women was introduced here.

The southern and eastern states, on the other hand, already had constitutions, which made it difficult to introduce women's suffrage. There, in those early years, women's suffrage was introduced only in Kansas (1912); between 1912 and 1914 there were twelve referendums, three of them in Ohio , all of which failed. But even holding a referendum was a success for the women's suffrage movement; in the southern states even the referendum initiatives were put down. When in 1914 the Senate voted on a constitutional amendment to introduce women's suffrage at the federal level and this failed due to a single vote, Anne Martin attacked the Senator from Nevada Key Pittman : he did not want blacks to have the right to vote. Martin told him he needn't worry, women's suffrage would only cement the dominance of whites anyway. White women in the southern United States became involved in the women's suffrage movement from the turn of the 20th century. They shifted the focus from an initially favored introduction at the federal level to the individual states in order to strengthen their position and advocated the right to vote for white women. The commitment to women's suffrage had lost its connection with the goal of racial equality, which had already been fragile since the 1860s.

Wyoming followed in 1869 . In Utah , women's suffrage was introduced in 1870, abolished in 1887, and re-guaranteed in 1896. Since Mormons made up the majority of the population here, women's suffrage was introduced here to defend polygamy .

The closest states were: Colorado (1893) and Idaho . Colorado was the first state in 1893 in which men voted in a referendum to vote for women. Washington followed in 1910 with the introduction of women's suffrage , and California in 1911 ; 1912 Arizona , Kansas and Oregon ; 1913 Alaska and Illinois (restricted); 1914 Montana and Nevada ; 1917 Arkansas , Indiana , Michigan , Nebraska , New York and North Dakota (for the presidential election), Ohio (women's suffrage was abolished that same year) and Rhode Island ; 1918 Oklahoma , Michigan, South Dakota and Texas (women suffrage in primary elections). In some states, restrictions such as reading and writing tests and taxes were still used after 1920 to prevent blacks from voting.

Development at the national level

The way to active women's suffrage

In 1910, a petition for women's suffrage was presented to Congress, which was signed by over 400,000 women. In the same year, President William Howard Taft addressed NAWSA, which is to be seen as recognition of the organization as a political influence.

In 1916 Alice Paul decided to attack the Democrats , who were in power at the time, for failing to introduce women's suffrage. President Woodrow Wilson , who was from the southern United States , believed that women's suffrage was a state matter and was unwilling to advocate it at the federal level. Paul founded the National Woman's Party in 1916 , and they voted in those states that had already introduced women's suffrage. The party organized campaigns there calling on women to vote against the Democrats and to show the political power of women. This had the absurd consequence that the party called for a line-loyal vote against democratic candidates at the state level, even if these candidates themselves campaigned for women's suffrage. This benefited the candidates who opposed women's suffrage. The activists' strategy failed. The Republicans supported the women's suffrage movement at the national level in 1916, but without much commitment. President Wilson did not deviate from his line that women's suffrage should be decided at the state level, not the federal level.

Between 1915 and 1920, the political clusters changed their attitude towards women's suffrage and spoke out in favor of it: it was now seen as the driving force behind winning votes, and they did not want to miss this plus point.

The success of the National Woman's Party resulted in NAWSA becoming more involved in promoting women's suffrage at the national level than in enforcing women's suffrage in each state. In 1916 an agreement was reached within NAWSA that, while national constitutional amendment was preferred, it also provided for key campaigns to be supported in the 36 states most open to women's suffrage. It also agreed to support efforts to get as many states as possible to pass the Illinois Act , which gave women the right to vote in presidential elections. As a result, six more states from the Midwest and the Northeast received the right to vote in the presidential elections.

Carrie Chapman Catt supported President Wilson after entering the First World War out of political calculation . However, their intention to achieve a constitutional amendment in cooperation with the president failed due to the lack of the necessary two-thirds majority in the Senate.

In November 1918, the Republicans won a majority in both chambers of parliament. The 19th Amendment to the United States Constitution , which introduced women's suffrage, was approved by both chambers, but had yet to be approved by the state parliamentary bodies. On May 21, 1919, Congress decided to pass the constitutional amendment to ratification by the states; this happened because of the upcoming presidential election in 1920, because women's suffrage had become an issue that promised votes. A corresponding resolution of the Senate followed on June 4, 1919. In most of the states of the North, Midwest and West of the United States, the constitutional amendment was adopted, in the southern states the fight against it continued. By March 22, 1920, 35 states had already signed this constitutional amendment, named after the women's rights activist Susan B. Anthony, the Susan B. Anthony Amendment , but 36 were necessary. The four states of Delaware , Tennessee , Connecticut and Vermont had yet to make a decision . Delaware refused. The decisive yes vote came from Tennessee, whose governor Albert H. Roberts signed on August 24, 1920. On August 26, 1920 the regulation became law. Connecticut soon agreed too.

Deprivation of the right to vote for women

Less than a decade after black women were given the right to vote, they were stripped of it. For this purpose, dubious measures were used that had previously caused black men to lose the right to vote. In Columbia, South Carolina , black women were told to be patient with registration; they waited and waited until it became clear that the women were also ready to queue for twelve hours to get their registration. The next day it was declared that voting was restricted to those who paid taxes on real estate worth at least $ 300. The women who met this requirement did not receive the constitution as a reading text for the test of whether they could read and write, as provided by the law, but parts of the civil and criminal code of the state. They then had to explain these laws, but refused because the law did not require it. As a result, their registration was refused. Such methods have denied most black women in the southern states their right to vote. When they turned to the white-dominated National Woman's Party for support, they were fobbed off on the grounds that this was a racial, not a women's issue, as black women were discriminated against according to the same criteria as black men.

Passive women's suffrage

The constitution of September 13, 1788 does not provide for gender restrictions on the right to vote for the two chambers. However, it was only introduced explicitly on August 24, 1920.

Development in Puerto Rico

On April 16, 1929, a law was passed giving all women who could read and write the right to vote and was to come into effect in 1932; this meant that most Puerto Ricans were effectively excluded from the election. In 1935 a law was passed that guaranteed universal suffrage.

Universal suffrage for men was recognized in the Jones Act for Puerto Rico in 1917.

See also

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 230.

- ↑ a b Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 231.

- ^ Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 233.

- ↑ Ellen Carol DuBois, "Working Women, Class Relations, and Suffrage Militance: Harriot Stanton Blatch and the New York Woman Suffrage Movement, 1894-1909," Journal of American History, June 1987, Vol. 74 Issue 1, pp 34-58 in JSTOR

- ↑ Alexander Keyssar: The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the United States. New York, Basic Books 2000, p. 206, quoted from: Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 232.

- ↑ a b c d e f Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 232.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 245.

- ↑ a b c d e Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 240.

- ↑ a b c d e Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 239.

- ^ Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 239/240.

- ↑ a b c d Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 241.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 235.

- ↑ a b c d e Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 237.

- ↑ a b c d e Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 236.

- ↑ a b c d e f Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 238.

- ↑ a b c d e f Caroline Daley, Melanie Nolan (Ed.): Suffrage and Beyond. International Feminist Perspectives. New York University Press New York 1994, pp. 349-350.

- ^ Rebecca J. Mead: How The West Was Won. Women Suffrage in the Western United States 1968-1914. , New York, New York University Press 2004, p. 167, quoted from: Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 239.

- ↑ a b c d e f Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 244.

- ↑ Act of April 7, 1893 extending the right to vote to women under Article 2, Paragraph 2 of the Colorado Constitution , confirmation by the Governor of Colorado of December 2, 1893 that the law was passed on the basis of the referendum of November 7, 1893 at 35,798 Approvals against 29,451 rejections.

- ↑ a b c d e Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 234.

- ^ Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 242.

- ↑ a b c d Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 243.

- ↑ - New Parline: the IPU's Open Data Platform (beta). In: data.ipu.org. Retrieved November 16, 2018 .

- ↑ June Hannam, Mitzi Auchterlonie, Katherine Holden: International Encyclopedia of Women's Suffrage. ABC-Clio, Santa Barbara, Denver, Oxford 2000, ISBN 1-57607-064-6 , p. 300.

- ^ Allison L. Sneider: Suffragists in an Imperial Age. US Expansion and the Women Question 1870-1929. Oxford University Press, New York, 2006, ISBN 978-0-19-532116-6 , p. 134.

- ↑ a b June Hannam, Mitzi Auchterlonie, Katherine Holden: International Encyclopedia of Women's Suffrage. ABC-Clio, Santa Barbara, Denver, Oxford 2000, ISBN 1-57607-064-6 , pp. 246-247.

- ^ Truman Clark: Puerto Rico and the United States 1917-1933. Pittsburgh 1975, ISBN 0-8229-3299-7

- ^ Allison L. Sneider: Suffragists in an Imperial Age. US Expansion and the Women Question 1870-1929. Oxford University Press, New York, 2006, ISBN 978-0-19-532116-6 , p. 117.