Golden bull

The Golden Bull is an imperial code of law written in the form of a document, which was the most important of the “basic laws” of the Holy Roman Empire from 1356 onwards . Above all, it regulated the modalities of the election and coronation of the Roman-German kings and emperors by the electors until the end of the Old Empire in 1806.

The name refers to the gold carved seal that six of the seven copies of the document were attached ; however, it was not used until the 15th century. Charles IV , during whose reign the Latin language law was promulgated, called it our sacred law book .

The first 23 chapters are known as the Nuremberg Code of Law and were drawn up in Nuremberg and announced on January 10, 1356 at the Nuremberg Hoftag . Chapters 24 to 31 are called the Metz Law Book and were promulgated on December 25, 1356 in Metz , on the Metzer Hoftag .

The Golden Bull is the most important constitutional document of the medieval empire. In 2013 it was declared World Document Heritage, with corresponding obligations for Germany and Austria.

history

Originally it was not the task of the medieval rulers to create new law in the sense of a legislative procedure . Since the time of the Hohenstaufen , however, the view that the king and future emperor should be seen as the source of the old law and that he also had a legislative function became increasingly popular. This resulted from the fact that the empire placed itself in the tradition of the ancient Roman Empire (→ Translatio imperii , Restauratio imperii ), and from the increasing influence of Roman law on the legal conceptions in the empire.

Accordingly, Ludwig IV (1281 / 1282–1347) could, without being contradicted , describe himself as standing above the law ; he is entitled to create law and interpret laws. Charles IV took this legislative competence for granted when he issued the Golden Bull. Nevertheless, the late medieval emperors largely renounced this instrument of power.

After returning from his Italian expedition (1354–1356), Charles IV convened a court day in Nuremberg. During this procession, Charles was crowned emperor in Rome on April 5, 1355. At the court day, basic matters should be discussed with the princes of the empire. Karl's main concern was to stabilize the structures of the empire after repeated power struggles over royal dignity. Such unrest should be ruled out in the future through precise regulation of the succession to the throne and the electoral process. On this point, the emperor and the electors quickly agreed. The rejection of the Pope's right to have a say in the German royal election was largely decided by mutual agreement. On other points Karl bought the approval of the princes, but he was unable to implement several projects to strengthen the central power of the empire. On the contrary, he had to make concessions to the princes about their power in the territories and at the same time secured many privileges in his own dominant center of Bohemia . The result of the Nuremberg deliberations was solemnly announced on January 10, 1356. This law, later referred to as the "Golden Bull", was expanded and supplemented at another court day in Metz at the end of 1356. Accordingly, the two parts are also referred to as the Nuremberg and Metz laws.

However, the Hoftag did not make decisions on all points that Karl wanted to regulate. So few decisions were made on the peace question and the Rhenish electors were able to prevent a decision on questions of coinage, escort and customs.

content

Overall, in large parts of the Golden Bull no new law was created, but rather those procedures and principles were written down that had emerged in the previous hundred years in the elections for the king.

Election of the king and emperor

On the one hand, the “imperial legal code” regulated in detail the modalities of the election of a king. The right to do this lay solely with the electors. As Chancellor for Germany, the Archbishop of Mainz had to convene the electors in Frankfurt am Main within 30 days of the death of the last king in order to elect the successor in the Bartholomäuskirche , today's cathedral. The electors had to take the oath to make their decision "without any secret agreement, reward or remuneration". On the other hand, the elected received all the rights not only of a king, but also of the future emperor .

Votes were cast according to rank:

- The Archbishop of Trier as Chancellor for Burgundy.

- The Archbishop of Cologne as Chancellor for Imperial Italy. Since Otto the Great (936) to the coronation of King Ferdinand I . (1531) the king was crowned in the Palatinate Church of Aachen . This church, founded by Charlemagne , was in the territory of the Archbishop of Cologne, so that he had to crown the king.

- The King of Bohemia as the crowned secular prince and ore tavern of the empire.

- The Count Palatine by the Rhine . His territory was in the old Franconian settlement area, so he became an archdean and in the absence of the Emperor of Germany he was imperial administrator in all countries in which non- Saxon law applied. The arch trustee was also the authority before which the king had to justify violations of the law.

- The Duke of Saxony as arch marshal and imperial administrator in all countries where Saxon law applied.

- The Margrave of Brandenburg as treasurer .

- The Archbishop of Mainz had the highest rank as Chancellor for the German lands and was the last to vote because of the possibility of the casting vote.

The rights and duties of the electors were sealed comprehensively and permanently when the king was elected. The election of a king was thus formally, as already explained in the Kurverein von Rhense , detached from the approval of the Pope and granted the new king full power of rule. An essential innovation of the Golden Bull was that, for the first time ever, the king was elected with a majority vote and was not dependent on the approval of all (elector) princes as a whole. For this, however, so that there would be no first or second class king, it had to be faked that the minority abstained from voting and so in the end "everyone agreed". A king could be chosen from the ranks of the electors with his own vote.

Although that was at the ceremony coronation as emperor generally held by the Pope, but in fact this was done recently with Charles V . His predecessor Maximilian I called himself "Elected Roman Emperor" from 1508 with the consent of the Pope. Instead of the coronation in Aachen from 1562, beginning with Maximilian II up to Emperor Franz II. In 1792, almost all coronations in the Frankfurt Cathedral took place after the election.

Further instructions

In addition, the Golden Bull stipulated an annual meeting of all electors. Consultations with the emperor should take place there. The bull forbade all kinds of alliances with the exception of rural peace associations, as well as the stake bourgeoisie ( citizens of a city who probably had city rights , but lived outside the city).

It regulated the immunity of the electors and the inheritance of this title. In addition, an elector received the right to mint coins , the Customs Law , the entitlement to exercise the unlimited jurisdiction and the obligation that Jews against payment of protection money to protect ( schutzjude ).

The areas of the electors were declared indivisible territories in order to avoid that the electoral votes could be divided or have to be increased, which meant that the first-born legitimate son was always intended as the successor in the electoral dignity of the secular electors. The actual aim of this bull was to prevent feuds of succession to the throne and the establishment of opposing kings. This was finally achieved.

The second part of the bull, the “Metz Law Book”, dealt in particular with questions of protocol, the collection of taxes and the penalties for conspiracies against electors. According to him, the sons and heirs of the electors were to be instructed in German , Latin , Italian and Czech .

Immediate effects and long-term consequences

The Golden Bull documents, formalizes and codifies a practice and development that has developed over centuries towards territorialization . The establishment of both secular and ecclesiastical sovereignty from around the 11th to the 14th century and parallel to this the creeping loss of power of the king in the course of territorialization are codified. With regard to this long-term development, Norbert Elias speaks of the conflict between “central power” and “centrifugal forces” in the course of the development from a feudal association of persons to an administrative-legal state.

The privileges of the electors, which had developed over time and solidified more or less under customary law, are codified:

- The electoral territories are inherited undivided to the firstborn.

- Privilegium de non evocando : subjects may only be summoned to the electoral court.

- Privilegium de non appellando : subjects are not allowed to appeal to any other court.

- Regalia fall to the electors.

Due to the extensive sovereignty of the individual territories, there was no central state in the area of the Holy Roman Empire, such as B. England or France, which rules from a powerful monarchical court and thus a political and cultural center. There is no linguistic uniformity and standardization, rather the respective territories retain their regiolects and develop largely autonomously . The territories set up their own universities, which teach independently of each other and have an important function in attracting special "state officials". Territorialization progressed in the following centuries, in the Peace of Westphalia of 1648 the division of Germany into independent territories was sealed, the central power continued to lose its competences until it was formally ended in 1806.

To this day, Germany is a federal state in which the states exert considerable political influence.

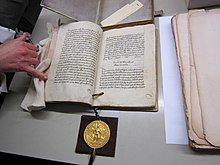

seal

Bulls are usually made of lead, only on very special occasions and in small numbers there are bulls made of gold, which are therefore extremely important and valuable. The obverse and lapel of the 6 cm wide and 0.6 cm high bulls are made of sheet gold. The obverse shows the enthroned emperor with orb and scepter , flanked by the (one-headed) imperial eagle on the right and the Bohemian lion on the left. The inscription reads: + KAROLVS QVARTVS DIVINA FAVENTE CLEMENCIA ROMANOR (UM) IMPERATOR SEMP (ER) AVGVSTVS (Charles IV., By God's grace Roman emperor, at all times multiples of the empire). The label reads: ET BOEMIE REX (and King of Bohemia). The reverse shows a stylized image of the city of Rome , on the portal it reads: AVREA ROMA (Golden Rome). The inscription reads: + ROMA CAPVT MVNDI, REGIT ORBIS FRENA ROTVNDI (Rome, the head of the world, controls the reins of the world).

Copies and their whereabouts

Seven copies of the Golden Bull have survived today. There is no evidence that there were other specimens. All copies consist of two parts: the first, consisting of chapters 1–23 resolved at the Nuremberg Reichstag, and the second with the Metz laws in chapters 24–31. Due to the size, the copies do not have the appearance of certificates , but are bound dragonflies . It is noteworthy that the Electors of Saxony and Brandenburg , probably for lack of money, decided not to issue their own copies.

The Bohemian copy is now in the Austrian State Archives in Vienna, Department House, Court and State Archives. It comes from the imperial chancellery, whereby only the first part is a sealed copy with a gold bull, the second part is an unsealed copy of an earlier second part of the Bohemian copy, which was probably only a concept. The copy was bound together with the first part between 1366 and 1378.

The Mainz copy is also in the Austrian State Archives in Vienna, Department of House, Court and State Archives. It comes from the imperial chancellery. The golden seal and the sealing cord are no longer there.

The Cologne copy is in the University and State Library Darmstadt . The clerk is unknown, maybe it's a wage clerk.

The Palatinate copy , which also comes from the imperial chancellery, is now in the Bavarian main state archive .

In the Trier copy in the main state archive in Stuttgart , which comes from the imperial chancellery, the bull with the remains of the silk cord is only loosely enclosed.

The Frankfurt copy is a copy of the original Bohemian copy, so the second part is based on the same template as the second part of today's Bohemian copy. It is located in the Institute for Urban History in the Carmelite Monastery , the former Frankfurt City Archives. It is a copy at the expense of the city, as the city, in connection with the rights guaranteed to it in the election of a king and in the first Reichstag, had an interest in a complete copy. Although a copy in character, it had the same legal status as the other copies.

The Nuremberg copy , which is kept in the Nuremberg State Archives , is only sealed with a wax seal and not a gold seal. It is a copy of today's Bohemian copy and was made between 1366 and 1378.

In addition to these seven originals, there are numerous copies (also in German) and later also prints, each of which is based on one of these templates. Particularly noteworthy is the magnificent manuscript of King Wenceslas from 1400 (see picture above), which is now in the Austrian National Library .

Transcripts

174 copies of the Golden Bull from the late Middle Ages and at least twenty other text witnesses from the modern era were found, increasing the number of copies named in the most recent edition by more than a quarter. Most of the Latin copies follow the Bohemian version of the Golden Bull. Most of the others follow the Palatine version; only a few pieces can be attributed to the Mainz or Cologne and only very isolated copies of the Trier version. The background to this is firstly the Roman-German royal or imperial dignity of the Luxembourgers and the Habsburgs ; secondly, the long-standing claims of the Bavarian Wittelsbachers to the electoral dignity , which were passed over by Pavia in contravention of the domestic Wittelsbach house contract ; and thirdly, the fact that the copies for Frankfurt and Nuremberg are diplomatic copies of the Bohemian version and thus contributed indirectly to its further dissemination. The copies come from the Rhineland , the southwest, Franconia and later Switzerland , from the Wittelbach and Habsburg south and the Bohemian southeast, as well as from the margraviate of Brandenburg , Prussia and Livonia as well as cities in Saxony, Thuringia and Westphalia . Further duplicates come from the chancellery of the French kings, from the Kingdom of Norway and the Margraviate of Moravia , from the port city of Venice and from the Roman Curia .

Most of the copies were made between 1435 and 1475. The first Latin duplicates were made in the late 14th century in the offices of the Electors of Cologne, Mainz and Bohemia and the Burgraves of Nuremberg. The well-known splendid edition for King Wenceslaus IV of Bohemia was created shortly after 1400. It was followed in the 15th century by copies for the Duke of Brabant , the Count Palatine of the Rhine, the Archbishop of Trier and the Habsburg Emperor. One can also expect duplicates for the Bavarian Wittelsbachers, the Dukes of Braunschweig-Lüneburg , the Grand Masters of the Teutonic Order and the Saxon Wettins . Other recipients of Latin editions were high clerics such as the bishops of Eichstätt and Strasbourg or prominent members of the Roman curia. The lower clergy and patriciate can also be found as users of Latin collections.

There were bilingual copies mainly on the Middle and Upper Rhine , but also in Franconia. All French versions come from the imperial city of Metz . They are only detectable since the end of the 15th century. The only Spanish translation from the 18th century is much more recent. Transfers into Dutch and Italian date from the printing era. A Czech translation probably does not exist because there was no longer any need in Bohemia as early as the 15th century.

reception

A total of five phases of reception can be distinguished. In the reign of Charles IV, the empire and territories were in the foreground of the interpretation. The Golden Bull was seen primarily as a collection of privileges or as a general privilege. Provisions on the feud and immunity of the Courlandes came under the crossfire of criticism. During the Great Occidental Schism , the Golden Bull was mostly interpreted as an imperial decree. The text was now interpreted with a view to the election of a king in Frankfurt, which was understood as an emperor's elevation without taking into account the papal approbation claims . The competing claims to rule of the kings Wenzel and Ruprecht represented the current political background. Under Ruprecht, the electors were also looked at in addition to the emperor, as the golden bull was understood as a wisdom of the electors. This corresponded to their increased share in imperial events. During the reign of Sigismund, the golden bull became the center of interest as an imperial law . The quaternions introduced at least since the Council of Constance all items as full members of the kingdom is modified and thus the dualism of Emperor and Elector. During this phase, the emperor was primarily understood as the highest judge, peacemaker, governor of the church and protector of law. The historical background for this was the church and imperial reform .

After the election of Frederick III. the golden bull became more and more a synonym for imperial law, but the imperial coronation also regained importance for the Habsburgs . The cure in Frankfurt, which was to significantly shape the modern view of the Golden Bull, and the mutual relationship between the two universal powers, which sparked the Protestant debate about the Golden Bull, even became the subject of university teaching for the first time. The canon law and Roman law were doing a whole new compounds for which the Golden Bull was an essential hub.

On January 2, 2006, for the 650th anniversary of the Golden Bull, the Federal Republic of Germany issued a postage stamp worth 1.45 euros.

The UNESCO has the "Golden Bull" as a German-Austrian joint nomination in the register " Memory of the World added". The admission was decided on June 18, 2013 at a conference in the South Korean city of Gwangju . For the 650th anniversary of the Golden Bull, the exhibition Die Kaisermacher took place in Frankfurt am Main in 2006/07 .

Translations and editions

- Wolfgang D. Fritz (arr.): The Golden Bull of Emperor Charles IV from 1356 (= Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Fontes iuris Germanici in usum scholarum separatim editi. Volume 11). Böhlau. Weimar 1972. Digitized

- Arno Buschmann (ed.): Kaiser and Reich. Munich 1984, p. 108ff. (German translation only).

- Karl Zeumer : The Golden Bull of Charles IV. First part: Origin and meaning of the Golden Bull . Second part: Text of the Golden Bull and certificates for its history and explanation . Weimar 1908. (Full text at Wikisource Part 1 , Part 2 )

- The Golden Bull . In: Lorenz Weinrich (Ed.): Sources on the constitutional history of the Roman-German Empire in the late Middle Ages (1250–1500). (= Selected sources on the German history of the Middle Ages. Freiherr-vom-Stein-Gedächtnisausgabe. Volume 33). Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1983, ISBN 3-534-06863-7 , pp. 314-393 (Latin edition with German translation).

literature

- Klaus-Frédéric Johannes : Comments on the Golden Bull of Emperor Charles IV and the practice of electing a king 1356–1410. In: FS Jürgen Keddigkeit, 2012, pp. 105–120.

- Klaus-Frédéric Johannes: The golden bull and the practice of the king's election 1356-1410. In: Archives for Medieval Philosophy and Culture . Vol. 14 (2008), pp. 179-199.

- Marie-Luise Heckmann : The German Order and the "Golden Bull" of Emperor Charles IV. With a preliminary remark on the origin of the quaternions (with edition of selected pieces) , in: Yearbook for the History of Central and Eastern Germany 52 (2006), p. 173 -226.

- Marie-Luise Heckmann: Real-time awareness and international appeal. The Golden Bull of Charles IV in the late Middle Ages with a view of the early modern era. With an appendix with the collaboration of Mathias Lawo: Copies of the Golden Bull, arranged according to traditional configurations. In: Ulrike Hohensee, Mathias Lawo, Michael Lindner, Michael Menzel and Olaf B. Rader (eds.): The Golden Bull. Politics - Perception - Reception (= Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences. Reports and treatises. Special volume 12). Vol. 2. Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-05-004292-3 , pp. 933-1042.

- Bernd-Ulrich Hergemöller : Princes, Lords, Cities of Nuremberg 1355/56. The emergence of the "Golden Bull" of Charles IV. (= Urban research. Publications of the Institute for Comparative Urban History in Münster. Volume 13). Böhlau, Cologne a. a. 1983, ISBN 3-412-00282-8 .

- Ulrike Hohensee, Mathias Lawo, Michael Lindner, Michael Menzel and Olaf B. Rader (eds.): The Golden Bull. Politics - Perception - Reception (= Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences. Reports and treatises. Special volume 12). 2 volumes. Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-05-004292-3 . ( Review )

- Erling Ladewig Petersen: Studies on the Golden Bull of 1356. In: German Archive for Research into the Middle Ages, Vol. 22 (1966), pp. 227-253. ( Digitized version )

- Bernd Schneidmüller : Monarchical Orders - The Golden Bull of 1356 and the French Ordonnances of 1374. In: Johannes Fried , Olaf B. Rader (ed.): The world of the Middle Ages. Places of remembrance from a millennium. CH Beck, Munich 2011, pp. 324-335.

- Armin Wolf : The "Imperial Law Book" of Charles IV (so-called Golden Bull) . In: Helmut Coing (Ed.): Jus Commune. Vol. 2, Frankfurt 1969, pp. 1-32.

- Armin Wolf: Golden Bull from 1356 . In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages (LexMA). Volume 4, Artemis & Winkler, Munich / Zurich 1989, ISBN 3-7608-8904-2 , Sp. 1542 f.

Web links

Digital copies of the individual copies

- Bohemian copy (Austrian State Archives, Department of House, Court and State Archives)

- Frankfurt copy (Institute for Urban History, Frankfurt am Main)

- Cologne copy (Digital Collections Darmstadt)

- Mainz copy (Austrian State Archives, Department of House, Court and State Archives)

- Palatine copy (Bavarian Main State Archive) Palatine copy (culture portal bavarikon)

- Trier copy (State Archive Baden-Württemberg, Department Main State Archive Stuttgart); The Trier copy on LEO-BW ; further explanations

Note: So far there is no digitized version of the Nuremberg copy online, only a CD-ROM available in the Nuremberg State Archives.

Source editions

- Edition of the Golden Bull in the MGH with introductory explanations

- Latin commentary, 17th century

- The Golden Bull in Early New High German in the Bibliotheca Augustana

more links

- Publications on the Golden Bull in the Opac of the Regesta Imperii

- The actual golden bull (the golden seal) in detail

- List of manuscripts for the German versions of the Middle Ages

- Bernd-Ulrich Hergemöller: Golden Bull, 1356 . In: Historical Lexicon of Bavaria

- Portrait of the Golden Bull at unesco.de

- The “Golden Bull” entry on the Register of the Memory of the World program

Individual evidence

- ↑ Golden Bull, Chapter 31 (translation by Wolfgang D. Fritz, Weimar 1978): “We therefore determine that the sons, heirs or successors of the exalted princes, namely the King of Bohemia, the Count Palatine of the Rhine, the Duke of Saxony and of the Margrave of Brandenburg, who probably learned the German language naturally as children, from the age of seven in Latin, Italian and Slavic [d. H. probably the Czech] language. "

- ↑ Wolfgang D. Fritz (edit.): The Golden Bull of Emperor Charles IV. From 1356. Weimar 1972, p. 14.

- ↑ Wolfgang D. Fritz (arr.): The Golden Bull of Emperor Charles IV from 1356. Weimar 1972, pp. 9–32.

- ↑ Postage stamp on the Golden Bull ( Memento of the original from September 28, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Golden Bull. Retrieved August 31, 2017 .