Gustav Holst

Gustav Theodore Holst ( English pronunciation : [ həʊlst ]; * September 21, 1874 in Cheltenham ; † May 25, 1934 in London ), born Gustavus Theodore von Holst , was an English composer . His best-known work is the orchestral suite The Planets .

Life

origin

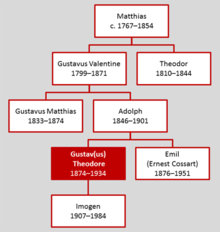

Gustav Holst's father Adolph von Holst came from a German-Baltic and a Latvian - Swedish family. On the maternal side, the family was predominantly of British - and far from Spanish - origin. Originally, Holst's family was probably of Scandinavian origin. By the late 17th century, branches of the Holst family settled in Poland and Germany.

Another branch of the family emerged in Russia when Christian Lorenz Holst moved with his family from Rostock to Riga in 1703. Gustav Holst's great-grandfather Matthias Holst (born 1759, died 1845) was a pianist, composer and harp teacher at the Russian Court in Saint Petersburg . He and his Russian wife Katharina Rogge (born 1771, died 1838) had their first child in 1799 with Gustavus Valentinus (born September 19, 1799, died June 8, 1870). A few years later the family had to flee and settled in London, where Matthias Holst worked as a music teacher and composer. In 1810 the second son Theodore (born September 3, 1810, died February 12, 1844) was born.

Gustavus Valentinus Holst followed in his father's footsteps as an adult and added the German “von” to his name in order to improve his reputation. He and his wife Honoria Goodrich of Norwich (died February 15, 1873) had five children, some of whom also became musicians:

- Gustavus Matthias (born 1833, died January 17, 1874)

- Catherine Maria von (born November 14, 1839, died January 21, 1874)

- Lorenz Henry von (born October 28, 1842, died February 28, 1913)

- Adolph, Gustav Holst's father (born February 5, 1846, died August 17, 1901)

- Benigna ("Nina"; born 1849, died 1920s).

After studying in Hamburg, Adolph von Holst settled in Cheltenham, the composer's birthplace. In July 1871 he married Clara Cox Lediard, the composer's mother. She was one of his students and the fifth child of Mary Croft Lediard and Samuel Lediard, a lawyer from Cirencester .

Gustav Holst's younger brother Emil Gottfried von Holst (later Ernest Cossart ; born September 24, 1876; died January 21, 1951) later worked as an actor.

childhood

Gustav Holst was born on September 21, 1874 as the first child of Adolph von Holst (born February 5, 1846, died August 17, 1901) and Clara von Holst, born. Lediard (born April 13, 1841, died February 12, 1882). On October 21, 1874, Holst was baptized Gustav Theodore in the All Saints' Church after his grandfather and great-uncle.

Gustav Holst's mother Clara died on February 12, 1882 after a stillbirth of a heart disease. Gustav Holst and his brother Emil came into the care of their aunt Benigna ("Nina") Holst, their father's sister. They stayed there until 1885, when Adolph von Holst married his music student Mary Thorley Stone (born?, Died around 1900). Mary Thorley Stone was the daughter of Reverend Edward Stone, pastor in Queenhill ( Upton-on-Severn ). She neglected Gustav and Emil in favor of their interests in philosophy and religion, which had a negative effect on his health in the form of asthma and myopia. With Gustav's father, she had two children of her own, Mathias Ralph and Evelyn Thorley.

His father encouraged young Gustav to play the piano as soon as possible; through the family music evenings he got to know Scottish and Irish folk music. In addition to the piano, he learned the violin and trombone.

In the same year Gustav Holst was sent to Cheltenham Grammar School. During Holst's school days, the school building was converted so that lessons took place in a former Presbyterian chapel. In 1889 he passed the Oxford Local Examination in English, history, Shakespeare, French, German and music.

While still at school - in 1887 - Holst had secretly tried to compose a cantata for choir and orchestra about the Roman folk hero Horatius after he had met Thomas Macaulay's Lays of Ancient Rome in class. Since he is not with the basics of harmony and counterpoint was familiar, he read the modern instrumentation and orchestration of Hector Berlioz . One day when he tried his music on the piano - alone at home - the result sounded very different from what Holst had expected. Holst was so disappointed that he stopped any further work on the cantata.

From 1888 onwards, Holst took part in a composition competition organized by the music magazine “Boy's own Paper” and achieved respectable results, including several first prizes.

Father Adolph encouraged Gustav's musicality by letting him take part in rehearsals; Gustav also sang in the choir of All Saints' Church and played the violin and trombone. Access to the organ for practicing and trying out your own compositions proved to be very valuable.

In December 1891 three works by Holst were performed: the Scherzo for small orchestra, the Intermezzo and the song Die Spröde based on a text by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. A symphony in C, composed in early 1892, also dates from this period .

education

Holst initially aimed for a career as a pianist . At the age of seventeen, however, he had to give up these plans due to an inflammation of the nerves in his arm that would stay with him for the rest of his life. In addition, Holst suffered from asthma and myopia throughout his life.

In 1892, Holst's application for a scholarship at Trinity College failed. His father then sent him to study counterpoint with the organist George Frederick Sims in Oxford. In Oxford he lived with his grandmother, Mary Croft Lediard. On his return from Oxford, Holst took a position as organist and choirmaster in Cotswold, Wyck Rossington, and gave music lessons.

On July 13, 1892, he was impressed by a performance of Richard Wagner's Götterdämmerung in London's Covent Garden . Holst was at least as influenced by the music of Arthur Sullivan , which was already expressed in 1892 in Holst's two-act opera The Lawnsdon Castle (also: The Sorcerer of Temkesbury ). In December 1892 it was performed in part and the following year in full and attracted initial attention. The success of the opera prompted Adolph von Holst to see his son's future in a career as a composer. On his advice, Holst applied - again in vain - for a scholarship at London's Royal College of Music , whereupon his father loaned the money to train relatives. During the entrance examination at the Royal College, Holst met his future friend Fritz Hart .

After Holst began studying at the Royal College of Music , his nervous disease worsened, so that he had to switch from the piano under Frederick Sharpe to the trombone under George Case. One of his other professors was William Stevenson Hoyte , who was also the organist at All Saints' Church and made Holst familiar with the cantus planus that he would later use in The Hymn of Jesus . Despite his counterpoint studies at Oxford, Holst had to deepen his knowledge in a special theory course before Charles Villiers Stanford accepted him as a composition student. Other teachers were WS Rockstro, Frederick Bridge, George Jacobi and Hubert Parry. Whether these teachers had any influence on his musical style is doubtful; so Holst himself said that he learned more about counterpoint in later years from William Byrd and Thomas Weelkes than from his college teachers. In addition to Fritz Hart, Holst became friends with Evlyn Howard-Jones , William Hurlstone , Samuel Coleridge-Taylor , Thomas Dunhill and later John Ireland .

When Fritz Hart visited him one day in his small room in Hammersmith , he was amazed that Holst could not afford a piano. To save money, Holst walked part of the way home to Cheltenham at the end of the semester. The lady to whom he dedicated his piece Introduction and Bolero for piano duet was probably Mabel Forty, whose humor and strong personality had impressed him.

Shortly before the beginning of the fall semester of 1893, he was impressed by a performance of Johann Sebastian Bach's Mass in B minor in Worcester Cathedral .

The children's opera Ianthe , for which Fritz Hart wrote the libretto, was a first compositional success . When the money raised by his father for Gustav's education ran out in 1895, Holst stepped up his efforts for a scholarship and was successful shortly before reaching retirement age. A little later, the one-act opera Beau Brummel - again with a libretto by Fritz Hart - was Holst's first work, to which he gave an opus number.

After the summer vacation of 1895, Gustav Holst met the composer and conductor Ralph Vaughan Williams . Both men had a lifelong friendship; They presented their current works to each other during the composing phase and gave each other suggestions for improvement. Both attended a college performance of Dido and Aeneas on November 20, 1895 , which established Holst's lifelong admiration for Henry Purcell .

Around this time Holst began to improve his scholarship as a trombonist in several chapels, but this did not fill him. The last collaboration with Fritz Hart was the unfinished, one-act opera The Magic Mirror . He also wrote a number of chamber music works.

In addition to his musical studies, he was also passionately involved in the Literary and Debating Society and the Hammersmith Socialist Society, in which he formed the Hammersmith Socialist Choir. In the latter, he fell in love with the young choir singer Emily "Isobel" Harrison, who would later become his wife. In connection with the Hammersmith Socialist Choir, Holst also worked on plays, which should prepare him for the later writing of opera libretti.

In the fall of 1896 he won a prize from the Magpie Madrigal Society for his choral composition Light Leaves Whisper, based on words by Fritz Hart.

In July 1897, Vaughan Williams gave him a job as organist and choirmaster at St. Barnabas' Church in South Lambeth ; after Holst had helped out a few times, the job went to John Ireland. Holst meanwhile continued the composition of songs and choral music, played on December 7, 1897 in the St. Queen's Hall in a concert conducted by Richard Strauss as well as accompanied Isobel and conducted on February 5, 1898 at the Grand Evening Concert of the Hammersmith Socialist Choir.

At the end of his studies in the year, he was offered to extend the scholarship for another year. Gustav Holst declined, however, because, in his opinion, it was time to go his own musical path.

First passion for Sanskrit

Gustav Holst first place he took in 1898 was that of a trombone and repetitor in the Carl Rosa Company in Southport ( Lancashire ), which had a reputation for representing an amateur standard. During a concert with the Carl Rosa Company in Scarborough , a book by Friedrich Max Müller (possibly a volume from The Sacred Books of the East ), which a friend had lent him, aroused Holst's interest in Sanskrit , which the composer has had for the rest of his life should. When a visit to the Department of Oriental Languages at the British Museum found that the books there were only available in Sanskrit and not in translation, he took Sanskrit lessons from Mabel Bode, manager of the County Theater in Reading . A friendship developed between them.

The first result of Holst's preoccupation with Sanskrit was the idea for a three-act opera called Sita , which he began to compose in 1899. The plot of the opera, held in the style of Richard Wagner , is based on the heroic epic Ramayana written by Valmiki and deals with the Indian goddess Sita . The opera was not completed until 1906. While working on Sita , Holst's musical role model Arthur Sullivan died in 1900 .

First professional steps and wedding

In the meantime, he composed the orchestral work Suite de Ballet and the Walt Whitman overture - a tribute to the poet Walt Whitman , which he was to set to music several times - in 1899 , and the Cotswold Symphony and the Ave Maria for eight-part female choir in 1900 . Parts of the opera Ianthe were performed again in 1899 and the work Örwald's Drapa from 1898 in 1900. In 1900 Holst finished regular tours with the Carl Rosa Company and became second trombonist in the Scottish Orchestra in Glasgow. The higher standard of the Scottish Orchestra compared to the Carl Rosa Company enabled him to deepen his orchestral knowledge.

On Sunday June 22, 1901, Holst and Isobel Harrison were married and moved to 162 Shepherd's Bush Road in Brook Green (part of the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham ). The first visitor to the newlywed couple was Fritz Hart . In 1907 daughter Imogen Holst (born April 12, 1907; died March 9, 1984) was born. She also became a composer and conductor and stood up for her father's work after Gustav Holst's death. On August 17, 1901, a few weeks after the wedding, Holst's father Adolph died unexpectedly at the age of 65. He was buried in Cheltenham Cemetery on August 21, 1901.

Gradually, Holst began to think about giving up the trombonist position in the Scottish Orchestra and becoming an independent composer with purely commercial works. In the December 1902 issue of the music magazine The Vocalist , Ralph Vaughan Williams campaigned for Holst's Songs Without Words . In April 1902 Holst celebrated another success with the no longer surviving children's operetta Fairy Pantomime of Cinderella , which was so successful and most likely in the same style as Ianthe . The highlight of the month, however, was the world premiere of the Cotswolds Symphony in the Bournemouth Winter Gardens on April 24, 1902 by the Bournemouth Municipal Orchestra under the direction of Dan Godfrey , which received several positive reviews. In August 1902 the Milanese publisher Sonzogno announced an international competition for a one-act opera; the prize money was 2000 pounds . Holst decided to take part in the competition with The Youth's Choice and managed to meet the deadline of January 31, 1903, just in time.

The inheritance from Holst's father enabled the young couple to make a short trip to Berlin in the spring of 1903, where they both met members of Holst's family who also lived in Germany. In Berlin, Holst worked as the first major result of his Sanskrit studies on an orchestral work about Indra , the Hindu god of rain and storm, who frees people from a kite while rain ends a dry period. As Fritz Hart later recalled, conductor Parry made sarcastic remarks during rehearsals at the Royal College of Music ; Holst then withdrew the composition. After returning from Germany, Holst learned that The Youth's Choice hadn't made it into the final selection. The prize money would have enabled Holst to give up the trombonist position at the Scottish Orchestra. However, he continued to concentrate on his work while Isobel made an income with tailoring. The couple now moved to 31 Grena Road, Richmond, south of the Thames. In addition to songs and other compositions, Holst also wrote a quintet, which he sent to the flautist Albert Fransella. The manuscript did not reappear until the 1950s; in 1983 the quintet was released.

Holst as a music teacher

The year 1904 finally brought a career turnaround for Holst: When Ralph Vaughan Williams gave up his teaching profession that year at James Allen's Girls' School in West Dulwich , South London, Holst was his successor, having previously represented him a number of times. Holst taught with enthusiasm and the teaching profession would stay with him until the end of his life. At James Allen's Girls' School, he was given time to compose, and the first to be written was The Mystic Trumpeter, based on the poem From Noon to Starry Night by Walt Whitman . In the same year, the premiere of the Suite de Ballet on May 20 at the first Royal College of Music Patron's Fund concert was a great success.

From autumn 1904 Holst also gave evening courses at the Passmore Edwards Settlement (later Mary Ward Center) in Bloomsbury. During Holst's activity there until 1908, Bach cantatas that were still unknown in England were performed. Isobel sometimes sang in the choir or played the cello or bass in the orchestra.

In early 1905, Holst decided to take part in the Ricordi-Milan competition with his opera Sita , which is about the Hindu goddess of the same name . Later on, Sita narrowly missed first place; according to Karl Hart's memories, the opera failed because of Holst's former professor Stanford.

In 1905, in addition to his previous teaching activities, Holst became musical director and singing teacher at St Paul's Girls' School in Brook Green , Hammersmith , where he was succeeded by Herbert Howells after his death . He managed to transfer his enthusiasm to his students.

Around this time, English folk music became another influence in Holst's work. In 1905 and 1906, the Norfolk Rhapsody , composed by Vaughan Williams, inspired Holst to also write a work that, like the friend's music, arranged folk songs into an orchestral work. The folksongs for the two-part composition, initially called Two Selection of Folksongs and later renamed A Somerset Rhapsody and Songs of the West , came from the Folksongs from Somerset collection . Holst's Two Selections first performed on February 3, 1906 in Pump Room , Bath , under the baton of Holst, who conducted the City of Bath Pump Room Orchestra , and met with applause from audiences and critics. A year later, Holst revised both parts of the Two Selections . While A Somerset Rhapsody became one of Holst's earliest popular works, the Songs of the West were not released.

In the initial phase of 1907, Holst began working on hymns from the Rigveda with his Vedic Hymns . Rigveda is from an earlier period than the Ramayana , which served as the source for Sita ; in fact, the Rig Veda is the oldest known work in Sanskrit literature. The hymns are invocations to gods like Agni , Ushas , Surya , Vayu and the Maruts .

In the spring of 1907, Morley College was looking for a successor to the late teacher HJB Dart. Since Vaughan Williams was not available because of his own obligations, he recommended Holst. Despite the already existing teaching activities, Holst accepted the position for financial reasons, as the birth of daughter Imogen was announced. Despite the large number of teaching commitments, he found the time to compose.

Because of exhaustion and depressive states, Holst spent a vacation in Algeria after 1908. He returned freshly relaxed and full of energy and began composing his opera Savitri . Like Sita , Savitri is based on the Indian epic Ramayana and describes the legend of Savitri and Satyavan , in which Savitri outwits death who had come to take her husband Satyavan with him. The news that Sita had been refused publication accelerated Holst's work on Savitri . The opera was completed and premiered eight years later in 1916, and published in 1923. The world premiere on December 5, 1916 under the direction of Herman Grunebaum in Wellington Hall in St. John's Wood (district in the City of Westminster in London ) evidently met with a positive response.

Working on Savitri took so long that Holst decided in 1908 to quit his position at the Passmore Edwards Settlement; the Holst family also moved from Grena Road to 10 The Terrace, Barnes. He continued his work at Morley College with enthusiasm and took his 18-month-old daughter Imogen to James Allen's Girls' School, where she mimicked his conducting gestures. He promoted her musicality by bringing her into contact with the piano.

During this time he changed his approach in his study of the Rigveda -Text and began a series of Choral Hymns from the Rig Veda to compose; the first group consists of the three hymns Battle Hymn , To The Unknown God and Funeral Hymn and was created in 1908. The second group was created in 1909 with To Varuna , To Agni and Funeral Chant . A third group followed in 1910, which, in contrast to the first two groups, consists of four hymns, which are accompanied by the harp rather than the orchestra: Hymn to the Dawn , Hymn to the Waters , Hymn to Vena and Hymn of the Travelers . In the first months of 1912 he concluded the Choral Hymns from the Rig Veda with the fourth group of four hymns to Agni, Suma, Manat and Indra.

In early 1909 he was commissioned to write The Vision of Dame Christian about Dame Christian, the mother of John Colet, the school's founder , for the centenary of St Paul's Girls' School . At first he was shocked that he should write the text for the play, but the rector wrote it himself. During the rehearsals he also met Vally Lasker, who was to become one of his closest assistants. The piece premiered on July 22, 1909; performing the play became a tradition at the school.

In 1909, Holst chose a passage from the poem Meghaduta by the Indian poet Kalidasa from the 5th century AD as the basis for The Cloud Messenger , a work for choir and orchestra in the chromatic style of Richard Wagner . The work is about a poet who sends a cloud with a message of love to his wife. The Cloud Messenger premiered on March 4, 1913 under Holst's direction, who conducted the New York Symphony Orchestra and the London Choral Society . To Holst's disappointment, the reviews of the work he considered to be one of his best were cautious. Holst edited the work for publication.

At Morley College, Holst supervised the preparations for the revival of Henry Purcell's opera The Fairy-Queen in the first half of 1911 . The musician JS Shedlock had previously been commissioned by the Purcell Society to reconstruct the work. When the project was about to go to press, Shedlock happened upon the manuscript of The Fairy-Queen in the library of the Royal Academy of Music . From November 1910 , students at Morley College, under Holst's direction, created a sheet music edition for the performance from 1,500 pages of musical text. This took place on June 10, 1911 in the Royal Victoria Hall with an introduction by Ralph Vaughan Williams and under the direction of Isidore Schwiller and received a positive response in the press.

When Holst became exhausted, he took a vacation in Switzerland in 1911. At Morley College, he was able to reduce his workload. On the other hand, he took on new teaching duties in early 1912 at the St Paul's Girls' School affiliated Wycombe Abbey School in High Wycombe , Buckinghamshire .

After Holst took over the leadership of the orchestra at St Paul's Girls' School in 1911, he began working on the St Paul's Suite the following year . The four-movement orchestral work was intended exclusively for a performance at the school. It was published in 1922.

On September 3, 1912, the sensational world premiere of Arnold Schönberg's Five Orchestral Pieces took place in the Queen's Hall . The work was performed again in January 1914. Most likely Holst attended at least one, maybe both, performances. The novelty of music also left its mark on him.

On January 3, 1913, Holst conducted his composition Beni Mora in Birmingham Town Hall at a conference and festival of the Musical League and the Incorporated Society of Musicians . The work irritated with violations of compositional rules. Nevertheless, the performance was an important milestone for Holst on the way to recognition.

"The planets"

In 1913, Holst went on vacation to Mallorca with Arnold Bax and Henry Balfour Gardiner . There Holst developed a steadily increasing interest in astrology and began to create horoscopes for his circle of friends. During the vacation, St. Paul's Girls' School was supplemented by a wing of the building, which was almost completely completed when Holst returned. In this context, a soundproof room was set up, which Holst then used to compose on weekends. The inauguration took place on July 1, 1913. The first work that Holst completed in the soundproof room was St Paul's Suite .

Also in 1913, the family Holst moved into a small cottage in the Monk Street two miles south of Thaxted ( Essex ). A few years later it was destroyed by fire; the last traces of the garden also disappeared through road expansion work. In Thaxted, Holst also took care of the church music and the church choir. At Pentecost 1916, Holst organized the first Whitsun Festival in Thaxted , during which the choirs of Morley College and St Paul's Girls' School performed together. The festival was a great success and took place annually from now on; it was only canceled in 1919 when Holst was not in town.

In his cottage in Thaxted, Holst began - inspired by his new interest in astrology - from 1914 to 1916 with the composition of the seven-movement orchestral suite The Planets , in which he characterized the then known seven planets of the solar system (except the earth). Arnold Schönberg's Five Orchestral Pieces , which had so impressed Holst, were an important inspiration . Much of the work was created in his soundproof room at St. Paul's College.

A first private performance of the planets , initiated by Balfour Gardiner, took place on September 29, 1918 in London's Queen's Hall under conductor Adrian Boult . According to a legend, when the Jupiter phrase was played, the cleaning ladies in the corridor began to dance. The first public performance of the planets took place - again under the direction of Adrian Boult and in the Queen's Hall - after the end of the First World War (but without Venus and Neptune ) and was Holst's greatest public success. But as the success grew, so did the interest of journalists and photographers in Holst, who disliked journalists and preferred to continue to lead an ordinary life. The more the journalists asked, the shorter Holst's replies became, until he implied with a silence that he considered the interview over.

According to the statement of the music critic and Holst's companion Clifford Bax , Holst lost his musical interest in astrology after the planets ; however, Holst continued to create horoscopes for his circle of friends.

First World War

While working on the planets - Holst had just finished the first sketch for Mars , the Warbringer - the First World War broke out. Holst signed up for military service, but was found unfit for health problems such as nerve inflammation in his arm, nearsightedness, and poor digestion.

Holst was suspected of espionage by the inhabitants because of the German sounding “von” in his name; his musical activity was thought to be a cover-up. Two residents from nearby Great Easton found his walks suspiciously, during which he questioned residents about the area, but police investigations did not reveal any suspicion. In the course of time, the residents were able to put their reservations about Holst down.

After the planets were completed - the orchestration was almost complete by the end of 1916 - Holst wrote the choral song This Have I Done for my True Love , which Holst considered his best polyphonic song. It is based on a medieval poem from William Sandy's collection Christmas Carols Ancient and Modern from 1833. Holst dedicated the song to his friend Conrad Noel, since 1910 Vicar of Thaxted.

In 1917 the Holst family moved from Monk Street to central Thaxted to a house called The Steps (now The Manse ), where they lived until 1925.

Towards the end of the war - right after the private performance of the planets - Holst gave several concerts for soldiers on behalf of the YMCA in Greece and Turkey in order to improve their morale. In connection with his service with the YMCA, he began to leave out the "von" in his name. In 1919, Holst turned down an offer to extend his business for another year and returned to England that summer. At the end of his YMCA employment, he organized a music competition. At Morley College, it was important to him to avoid administrative activities as much as possible and to concentrate as much as possible on teaching composition.

After the end of the war

After his return to Thaxted, Holst processed his insight into the futility of war in the Ode to Death in memory of musician colleagues and friends like the young composer Cecil Coles , who had perished on the battlefield.

Between 1919 and 1923 Holst taught composition at the Royal College of Music and Reading University . Here he gave courses in harmony and counterpoint . At the beginning of 1920, Holst's work The Hymn of Jesus , composed in 1917, was performed and left a deep impression on the audience. The composition is based on The Apocryphal Acts of St John by the theosophist George Robert Stow Mead , written in Greek, and depicts a hymn sung by Jesus Christ and his disciples after the Last Supper . For the composition of the work Holst learned the basics of the Greek language. In 1919 and 1920 Holst wrote the libretto for his comic opera The Perfect Fool , in which Holst satirized the operas of Claude Debussy , Giuseppe Verdi and Richard Wagner's Parsifal . Holst's request to have the libretto written by his former student Jane Joseph or by his friend Clifford Bax had previously failed. In The Perfect Fool , Holst took over some ideas from the similarly satirical opera Opera as She is Wrote, written in 1918 . Work on The Perfect Fool was completed in 1922.

After a visit to Thomas Hardy , a writer he admired in Dorset , Holst began working on Egdon Heath based on Hardy's The Return of the Native . The premiere took place - a few weeks after Hardy's death - on February 12, 1927 in New York; Walter Damrosch conducted the New York Symphony Orchestra . Because of the novelty of the musical idiom, the audience reacted cautiously to the work.

After a brief visit to his reading student W. Probert-Jones in Derbyshire , Holst came up with the idea of an overture. As he wrote to Probert-Jones, the work developed into a fugue during the compositional work . The work, later the Fugal Overture , was largely created in Holst's soundproof room in St Paul's College and was completed on January 4, 1923. It was first heard as an overture to the performances of The Perfect Fool at Covent Garden and received mixed reactions.

During concert rehearsals in Reading on the 300th anniversary of the death of the composers William Byrd and Thomas Weelkes , who were admired by Holst , Holst slipped on the concert desk in February 1923 and hit the back of his head. Holst ignored the doctors' advice to take it easy and suffered a nervous breakdown, whereupon he was given several weeks of strict rest. Philipp Collis and Ralph Vaughan Williams took over his teaching activities at Morley College, Balfour Gardiner that in Reading, until a successor was found. During his compulsory break of several weeks, Holst gathered the energy that he would need soon afterwards, as he had accepted an invitation from the University of Michigan to a concert festival. As long-term effects occurred a year after his accident, Holst gave up a large part of his teaching activities and only continued them at St. Paul's College.

On May 14, 1923, the opera The Perfect Fool premiered at the Royal Opera House , Covent Garden , conducted by Eugène Aynsley Goossens , who conducted the British National Opera Company . Because of his stay in Michigan in the USA , Holst was unable to attend the premiere. Audiences and critics reacted with confusion to the plot of the opera. In the summer and fall of 1923, Holst finished the work on the recordings of the planets that he had started the previous year in the Columbia Graphophone Company studios . The work was made difficult by the limited possibilities of the studios. After the success of sound recording, The Planets were recorded again in 1926 when new electronic recording methods had been developed. In the mid-1920s, listening habits changed with the advent of radio; there was no longer any need to travel to listen to music. In the early months of 1924 the BBC broadcast many of Holst's works. Occasionally, Holst asked the BBC what music was being played, even if it was of a different style than his own. During the year he made further gramophone recordings for Columbia, including the St Paul's Suite on August 24th.

Falling popularity

Holst began work on his next opera At the Boar's Head . As he read William Shakespeare's Henry IV and looked through some of his daughter Imogen's folk sheet music, he found that some of the melodies matched Shakespeare's words. By autumn 1924 the sketches were almost complete. The British National Opera Company wanted to produce the opera in its next season in early 1925, so Holst was pressed for time to work out the score. Malcolm Sargent conducted the premiere of the opera on April 3, 1925 at the Manchester Opera House . But the audience had difficulties following the opera because, on the one hand, it did not fit into the usual categories of operas. On the other hand, one critic suggested that Holst was wrongly assuming that the audience had detailed knowledge of Shakespeare's plays.

On October 7, 1925, the First Choral Symphony , whose composition Holst had begun a year earlier, was performed. The premiere took place in the Town Hall in Leeds under the direction of Albert Coates , who conducted the London Symphony Orchestra and the Festival Chorus , and with Dorothy Silk as soprano soloist. A poem by John Keats served as a model . A second performance with the same performers followed on October 29 in London's Queen's Hall . The audience and most of the critics reacted negatively to both performances. Holst's plans for another work of this kind, a Second Choral Symphony , did not get beyond the stage of a few sketches from November 1926.

After the failure of At the Boar's Head and the First Choral Symphony , Holst's popularity began to decline. The audience began to notice that Holst's previous successes would no longer be repeated; instead, he wanted to go whatever route his imagination and curiosity dictated, whether the audience wanted to follow him or not. Biographer Michael Short defends Holst for his strength in having retained his individuality despite the influence of contemporary composers such as Arnold Schönberg , Igor Stravinsky , Maurice Ravel and Béla Bartók .

From 1925 to 1928 there were numerous lectures and festivities such as the six-part lecture series “England and her Music” at Liverpool University organized by the Choral Circle at the Liverpool Center of the British Music Society from October 1925. Another series of lectures, this time on orchestral music, took place in Glasgow from January 15 to February 13, 1926.

In October 1927, at the invitation of George Bell, Dean of Canterbury, Holst began work on The Coming of Christ , the music for the stage production by John Masefield to be performed in Canterbury Cathedral . Despite protests from fundamentalists, the performances from May 26th to 29th 1928 were a great success with 6,000 visitors. Another performance at Pentecost 1929 failed due to organizational reasons.

From December 20, 1927 to January 19, 1928, Holst spent his Christmas holidays in Vienna and Prague. In his stopover in Munich he saw a performance of Richard Strauss ' Salome . On Christmas Day in Vienna he heard a Bruckner Mass and Ludwig van Beethoven's Fidelio and over the next few days he visited the Schubert House and the Haydn Museum, among others. From January 6th he was in Prague, where he visited the Mozart House and met famous colleagues like Leoš Janáček and Alois Hába . His name was already known through the performance of the Fugal Ouverture a few weeks earlier. In Prague he saw Hoffmann's stories by Jacques Offenbach and Bedřich Smetana's Two Widows . In the short term, he decided to detour to Leipzig, where he Die Fledermaus by Johann Strauss saw and the Thomas church visited and the Bach monument. On January 19th he traveled back to England.

During a lecture stay in Shrewsbury over Easter 1928 he began to work on two new works, the later A Choral Fantasia and the one-act opera The Tale of the Wandering Scholar, based on Helen Waddell's The Wandering Scholars, about a traveling student who asks a farmer's wife for food and convicted of marital cheating with a priest.

At the end of 1928 he found himself unable to fulfill the commission for a piece for the BBC military band, which he had received the year before, nor to write a piece to be performed at Canterbury Cathedral at Easter . As a result, he saw the need for a vacation and set out for Italy on December 20, 1928. Holst traveled to places such as Rome, Naples, Palermo, Syracuse, Florence, Bologna, Venice and Milan (where he saw Gioachino Rossini's Il barbiere di Siviglia ), although stations like Rome or the ruins of Pompeii impressed him rather moderately. In Venice he received news that one of his former students, Jane Joseph, had died at the age of 35. Shortly after his return from Italy, he traveled to the USA to accept the invitation from the American Academy of Arts and Sciences , which he had accepted during his trip to Italy.

Holst's creativity was reawakened by the Italian vacation, which among other things resulted in the Twelve Songs based on poems by Humbert Wolfe. On the other hand, in August 1929 he began work on the long-planned Double Concerto for two violins and orchestra, after having heard Johann Sebastian Bach's Double Concerto under Jelly d'Arányi and Adila Fachiri two years earlier . In September 1929 he was able to present the Double Concerto to Jelly d'Arányi and Adila Fachiri as dedicatees. The Twelve Songs premiered on November 7, 1929, and the first draft of The Wandering Scholar was completed on January 13, 1930 . For the award of the gold medal of the Royal Philharmonic Society in April 1930 (the previous month's prize winner was Ralph Vaughan Williams), Jelly d'Arányi and Adila Fachiri played the Double Concerto in a concert in the Queen's Hall under the direction of Oskar Fried .

Holst now saw himself in a position to put into practice the piece commissioned by the BBC a long time ago. From this came Hammersmith , which depicts the quiet course of the Thames in the London borough of Hammersmith in contrast to the hustle and bustle of the surrounding streets. By October 1930, Holst had completed Hammersmith in a version for two pianos. The months of November and December of 1930 were filled with final work on A Choral Fantasia , Hammersmith and The Tale of the Wandering Scholar . Although the BBC's Wireless Military Band was scheduled to perform Hammersmith in 1931, the piece was not performed until several decades after Holst's death.

For the 1931 film The Bells, about an inn owner who commits murder and is tormented by a guilty conscience, Holst was commissioned to compose the score; in addition, he had an extra appearance in a scene in a crowd. Although the producers of the film were in a hurry because they had taken care of the music for the film relatively late, Holst still had the time for a previously planned vacation in Normandy. However, Holst's enthusiasm for his assignment waned when, on the one hand, after completing the film music, the producers cut the film and asked Holst to make appropriate changes to the music and, on the other hand, during a test screening of the film, the music did not sound as much as Holst due to the poor quality of the speakers intended it. Both the film and Holst's music for the film are now considered lost.

United States

The end of 1931 was Gustav Holst an invitation from the American Harvard University to take a guest lecturer for composition and May 1932 from February. In addition, he was invited by the Boston Symphony Orchestra to play some of his works in January 1932. During his stay in America he had a lot of time to compose despite his teaching commitment. At the same time he was surprised that the students wrote theoretical treatises on compositions instead of composing themselves. In private he met with brother Emil and niece Valerie (born June 27, 1907, died December 31, 1994).

Sickness and death

At the end of March 1932, Holst was diagnosed with gastritis due to an ulcer on the duodenum . At first, Holst was able to recover and continued his work both in America and after his return to England. At the end of April 1934, Holst was admitted to the Beaufort House Clinic in the London borough of Ealing . Because of his poor health, the planned operation had to be postponed for three weeks; the three-hour operation finally took place on May 23rd. Two days later, on May 25, 1934, Gustav Holst died of a heart attack.

Holst's body was cremated in the Golders Green crematorium on May 28, 1934; his ashes were buried at Chichester Cathedral in Sussex . On June 19, 1934, a memorial service was held at St. Paul's Girls' School. On June 22nd, the BBC held a memorial concert in Holst's honor, including three movements from the Suite de Ballet , three movements from the chorale Hymns from the Rig Veda , Egdon Heath and the Ode to Death .

Honors

In his hometown of Cheltenham, a fountain with a statue of Holst was erected in Holst's honor . A museum has been set up in his birthplace at 4 Clarence Road. The asteroid (3590) Holst , discovered on February 5, 1984, was named after the composer.

reception

Gustav Holst, who is classified as a composer of the late Romantic period, achieved great popularity primarily through his seven-movement orchestral suite The Planets ( The Planets , 1914–1916). From this the sentence about Mars, the god of war, has even developed into an independent hit. This music became the treasure trove of many American film composers such as Danny Elfman , Elliot Goldenthal , Shirley Walker , Hans Zimmer and John Williams . Other orchestral works - such as the St Paul's Suite , which is based on the music of the Baroque era - have not achieved comparable fame. His opera Savitri was staged by Graham Vick at the Scottish Opera in the 1970s .

Holst's music had a lasting impact on the younger generation of British composers. Since 1961 he has given its name to Holst Peak , a mountain on Alexander I Island in Antarctica .

Works (selection)

Operas / stage works

Orchestral works

|

For wind band / military band

Vocal works

|

literature

- Imogen Holst: Holst. Faber & Faber, London 1974

- Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, ISBN 978-1-906451-82-0

Web links

- Works by and about Gustav Holst in the catalog of the German National Library

- Holst Birthplace Museum

- List of works (on www.gustavholst.info)

- Gustav Holst (on www.gustavholst.info)

- Sheet music and audio files by Gustav Holst in the International Music Score Library Project

- Gustav Holst in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Michael Struck-Schloen: May 25, 1934 - anniversary of the death of the composer Gustav Holst WDR ZeitZeichen on May 25, 2014 (podcast)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 1

- ↑ a b c d e f Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. XII – XVIII

- ↑ a b Lot 193 - Reiss & Son. Retrieved on May 9, 2020 (German).

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 1–2

- ↑ a b c d e Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 2

- ↑ a b Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 3

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 3–4

- ^ A b Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 4

- ↑ a b Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 6

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 6-7

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 7

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 7–8

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 8

- ↑ a b c Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 9

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 9-10

- ↑ a b c d Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 10

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 11

- ↑ a b Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 12

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 13

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 13-14

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 14-15

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 15

- ^ A b Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 16

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 16-17

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 17

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 17-18

- ^ A b Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 18

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 19

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 19-20

- ↑ a b Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 20

- ^ A b Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 22

- ↑ a b Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 21

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 21-22

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 22-23

- ↑ a b Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 23

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 23-24

- ^ A b Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 24

- ↑ a b c Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 25

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 26

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 27

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 28

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 28–29

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 29

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 30

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 31

- ↑ Fritz B. Hart: Early Moments of Gustav Holst. In: Royal College of Music Magazine , Volume 39, No. 2, 1943, pp. 43-52, pp. 84-89

- ↑ a b c d Eckhardt van den Hoogen: ABC of classical music. The great composers and their works. Eichborn, Frankfurt am Main 2002, Lemma Holst, Gustav.

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 32–36

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 36–37

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 38–39

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 39–41

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 41–42

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 43–44

- ^ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 45–46

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 49

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 89–90

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 46

- ^ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 48

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 46–47

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 50–51

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 52–54

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 59

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 48–49

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 50

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 51

- ^ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 65–67

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 56–57

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 58

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 58–59

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 63–65

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 62

- ^ A b Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 65

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 67–69

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 69–70

- ^ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 72–73

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 85–87

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 118–119

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 122

- ^ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 127–128

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 143

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 74-83

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 73

- ^ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 100-102

- Jump up ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 83

- ↑ a b Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 77-78

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 90–91

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 84

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 94

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 99-100

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 103–111

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 100

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 108-109

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 99–111

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 111

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 112–116

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 92

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 94–96

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 117–118

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 111–112

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 97-98

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 119

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 127

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 169–170

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 128–129

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 133

- ^ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 133-138

- ^ Franklin Mesa: Opera: An Encyclopedia of World Premieres and Significant Performances, Singers, Composers, Librettists, Arias and Conductors, 1597-2000. McFarland, Jefferson / London 2013, ISBN 978-0-7864-7728-9 , p. 209 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 135-137

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 138

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 159

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 144

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 146–150

- ^ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 148–149

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 140–141

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 152–155

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 160

- ^ A b Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 155

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 156

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 167–168

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 156–158

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 157

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 166–167

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 172–174

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 180

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 168–169

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 171–172

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 175–176

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 177-179

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 177

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 179

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 179-180

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 182

- ^ A b Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 183

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 184

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 185

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 188-189

- ^ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 192

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 190–192

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 194ff

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 197

- ^ Actress Valerie Cossart died of pneumonia on Dec. 31. She was 87. Retrieved May 9, 2020 .

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 196

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 199–200

- ^ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, pp. 209-210

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 210

- ↑ Michael Short: Gustav Holst - The Man and his Music , Circaidy Gregory Press (first published by Oxford University Press), 1990, new edition 2014, p. 211

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Holst, Gustav |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Holst, Gustav Theodore (full name); Holst, Gustavus Theodore von (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | British composer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 21, 1874 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Cheltenham |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 25, 1934 |

| Place of death | London |