Henry Morton Stanley

Sir Henry Morton Stanley (born January 28, 1841 as John Rowlands in Denbigh , Wales , † May 10, 1904 in London ), also Bula Matari ("who breaks the stones"), was a British-American journalist , Africa explorer and author. He became known through the search for David Livingstone and the exploration and development of the Congo on behalf of the Belgian King Leopold II.

Childhood (1841-1856)

The birth registry of the Welsh town of Denbigh reports the birth of an illegitimate child on January 28, 1841: "John Rowlands, Bastard ". The future Henry Morton Stanley suffered all his life from his illegitimate birth. His mother, Betsy Parry, worked as a housemaid and gave birth to four other illegitimate children in the years to come. She never told her son who his father was. There is speculation that it could have been John Rowlands, a well-known drinker, or a married lawyer named James Vaughan Home.

The mother initially left her child in the care of the grandfather. After his death - Henry Morton Stanley five years was old at that time - initially gave him his uncle for care in a family and later, when he no longer wanted to pay the allowance, in the workhouse St. Asaph's Union Workhouse in the small town of St Asaph. An investigation later found that the elderly residents of the house "had all kinds of vices." The leader, an alcoholic, took all liberties towards the residents. The children shared beds in twos, and when they were not being abused by adults, the older ones tormented the younger ones, even at night. For Henry Morton Stanley, this led to a lifelong fear of physical closeness and sexuality.

After all, staying in this workhouse gave him a certain degree of schooling. He was a good student, particularly interested in geography , and received a Bible dedicated to him by the bishop for his good work .

His mother met Henry only once during this period, when he was about nine, and she brought two more children to St. Asaph.

America (1856–1861)

At the age of 15 he left the workhouse voluntarily - unlike what he himself portrayed. He worked in various positions as a day laborer and finally, at the age of 17, he was hired on the Windermere , a ship that sailed to New Orleans . Once there, he was looking for work and introduced himself to the cotton merchant Henry Hope Stanley, whom he was able to impress with his price Bible.

Rowland's descriptions of this time - and probably not only this - differ from reality. He writes that he lived with the Stanleys, that he was adopted and that he accompanied the Stanley couple on their travels. Unfortunately, first the woman and then suddenly the man died in 1861. According to the New Orleans city register , the elder Stanley did not die until 1878, seventeen years later. He and his wife had adopted two children, but both were girls. His young employee Rowlands had never lived with him either, and eventually Rowland and Henry Hope Stanley fell out so much that they broke off contact.

Soldier and scribe (1861–1867)

In 1861 the young man, who now called himself Henry Stanley (Morton later added), joined the Confederate Army to fight in the American Civil War. In April 1862 he was captured at the Battle of Shiloh in Tennessee and taken to a prisoner-of-war camp near Chicago . Anyone who defected to the troops of the Union was allowed to leave the camp. Because typhoid fever was involved in the prison camp , Stanley decided to take this step. He fell ill in the Army of the Northern States and was then retired.

He was first hired on various ships of the merchant navy and in 1864 again with the Union navy . Because of his beautiful handwriting, he was made a ship scribe on the Minnesota . Shortly before the end of the war in 1865, he deserted and made his way to St. Louis , where he got a contract as a freelance correspondent for a local newspaper. He wrote reports from the Wild West : Denver , Salt Lake City , San Francisco . In the entourage of Major General Hancock , he took part in the Indian Wars. Although the year of his reporting was marked by peace negotiations, he wrote about the dramatic battles that awaited his publisher. In doing so, he piqued the interest of James Gordon Bennett Jr. , editor of the New York Herald , a tabloid .

New York Herald (1867-1878)

Bennet recognized Stanley's talent as a journalist and sent him to Abyssinia as a war correspondent to report on the unrest there. Stanley bribed the chief telegraph while he was passing through Egypt , thereby ensuring that his reports from the front were telegraphed first, even if other reports had arrived beforehand. Luck was with him. The day after the only major battle, of all things, the telegraph cable to Malta broke , immediately after Stanley's report was (the only one) broadcast. His publisher was delighted.

The Herald made him a permanent special correspondent and subsequently sent him to Spain , among other places, to report on the civil war there, in which Queen Isabella II lost her throne. In Madrid , according to Stanley's own legend, he received a telegram from his publisher on October 16, 1869, which immediately ordered him to Paris . There Bennett gave him the order "Find Livingstone!"

- "Draw a thousand pounds now, and when you have gone through that, draw another thousand, and when that is spent, draw another thousand. . . and so on; but find Livingstone! "

Africa

The Search for Livingstone (1870/71)

From the Scottish missionary and Africa explorer David Livingstone , a doctor who traveled on behalf of the London Missionary Society , there has been no sign of life since he set out on a research trip to the East African Lakes region in 1866. Although Stanley later made the story very dramatic, he didn't leave until a full year later. In between he reported for his newspaper about the opening of the Suez Canal , about excavations in Jerusalem and finally from Constantinople . It was not until 1870 that he set out from Bombay to find Livingstone.

As he had learned in the Abyssinian War, he set out with a huge entourage, 190 men, only two other British, the rest of the African porters. He moved from the east towards Central Africa and met a European on November 10, 1871 in Ujiji , near Lake Tanganyika . "Doctor Livingstone, I presume?" - "Doctor Livingstone, I suppose", he is supposed to have said. Since Stanley's European companions did not survive the trip, the Africans were never questioned and Livingstone did not write anything down until his death a year later, only Stanley's report is available.

The two men were very different: here the missionary Livingstone, who loved Africa and the Africans, learned their languages and made no profit from his travels. There Stanley, who honestly admitted he loathed the continent with all his heart. His books about Africa were then also called Through the Dark Part of the World or In Darkest Africa .

While in Africa, Stanley wrote many letters to his fiancée Katie Gough-Roberts, a young woman from his hometown of Denbigh, which he also sent her from ports. In one he confessed his true origins, illegitimate birth and unhappy childhood. After his return he found that she had married someone else in the meantime. Stanley, who was afraid all his life that his origins would be known, tried to get these letters back, but to no avail.

The Royal Geographical Society received Stanley with arrogance, for they too had sent out an expedition to find Livingstone, but too late. The authenticity of the letters he had brought back from Livingstone was doubted and Queen Victoria received him, but found him to be a "hideous little man".

Second expedition to Africa, 1874–1877

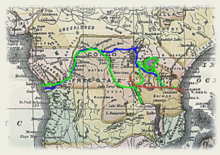

The aim of the second expedition was to find out where the Nile comes from. Livingstone thought that the Lualaba was the source of the Nile, while the British John Speke thought that the Nile rises on the north bank of Lake Victoria . But Stanley also wanted to prove that the success of his first trip was not a fluke. Not only did he set out with 359 men, he also had a ship with him, the Lady Alice , dismantled into individual parts. The ship was named after his fiancée Alice Pike, after whom he was to name several other geographical discoveries, such as Alice Island and Alice Rapids . But on his return he found (once again) that the fiancée had meanwhile married another, a railroad owner from Ohio .

In just three months, 150 men had died - some murdered by hostile tribes, some through disease, and some driven to death by Stanley. Stanley, who himself had changed fronts and deserted, had no mercy on deserters. She was waiting for the hippopotamus whip or they were being driven into the swamps.

His expedition lasted almost 1,000 days. He covered about 11,000 kilometers. Again none of his white companions survived. When he arrived in Boma on the Congo Estuary , Stanley was 36 years old, but emaciated from the exertion and white-haired early. In Uganda he discovered another lake in 1876, which he named after Albert Edward ( Edwardsee ). He wrote his first articles, and on his return to England he gave lectures and wrote books.

He strove to incorporate Central Africa and the Congo into the British colonial empire, but no one in the United Kingdom took up his ideas.

Leopold II and the Congo

Leopold II of Belgium read his reports. The young monarch was anxious to acquire colonies . Several attempts to obtain such had already failed. Leopold had initially founded a philanthropic society for exploring the Congo. In September 1876 he organized a major geographic conference in Brussels to explore the Congo.

On June 10, 1878, he met Stanley and the two made a deal. Stanley would acquire the Congo for the king, Leopold would see to it that formally everything was in order. They signed a five-year contract. Stanley received money from this, but had to raise additional funds to finance his expeditions. He went on a lecture tour and was even able to get mission societies to donate money.

Stanley meanwhile collected sales contracts for the land around the river. The tribal princes and chiefs who signed the papers in the unfamiliar language probably didn't know what they were doing. A clause in the contracts stated that not only the land, but also the labor of the residents would become the property of Leopold.

Stanley was Leopold's official representative in the Congo for five years and began building a runway from the mouth of the Congo River along the Congo Falls, 200 km long, to Stanley Pool (now Pool Malebo ), from where the Congo was navigable. Many of the forcibly recruited locals perished in this project. Stanley's sometimes reckless approach was heavily criticized in England and earned him the African nickname Bula Matari ("who breaks the stones").

Small steamships were taken piece by piece to Stanley Pool and assembled. Stanley founded a town which he named Leopoldville (now Kinshasa ) after his patron . Further stations were planned and built along 1,500 kilometers of the river. All of this, it was externally presented, in the service of science and in the fight against slavery .

Despite all these activities, Stanley and Leopold were initially able to maintain their good reputation. In 1884 Stanley took part in the international Congo Conference , which took place in Berlin on the initiative of Bismarck . The Congo was given to Leopold as a personal property for him to develop. Officially, Leopold and Stanley parted ways after five years, but Stanley was secretly still on the king's payroll.

In 1889 a major conference against slavery was held in Brussels . Slave traders were traditionally Arab merchants, so the conference was not a problem for the European participants. Leopold had Stanley appear at the conference in order to consolidate his position at the conference and at the same time to coax a loan of 25 million francs from the Belgian parliament . Stanley's work had made it possible for a private individual - Leopold II - to own 2.5 million square kilometers of land and the labor of the residents.

The Emin Pasha Expedition

In the meantime, Stanley took on other assignments. In Sudan , which had come under the rule of the Ottoman viceroys of Egypt from 1821, the Mahdi uprising broke out in 1881 . After the withdrawal of the Anglo-Egyptian troops from Sudan, the German researcher Emin Pascha asserted himself as governor of the southernmost province of Sudan Equatoria . Emin Pascha, bourgeois Eduard Schnitzer, had to learn that the British were not making any move to retake Sudan. So he wrote a letter to the Times asking for help. At the same time, the leader of the Mahdists, Abdallahi ibn Muhammad , demanded that Queen Victoria come to Sudan and convert to Islam . The resulting outrage in the British population led to the fact that the funds for an expedition to liberate Emin Pasha were quickly raised. Stanley was assigned to lead the expedition. He had to ask Leopold to release him from his obligations. He did this on the condition that Stanley did not take the shortest route, but had to travel through an as yet unknown part of the Congo. He was also supposed to persuade Emin Pasha to remain as governor, but to submit to the Congo. The expedition, which had already set out for Zanzibar , was therefore diverted to the mouth of the Congo.

Stanley prepared the trip well, some aspects seem downright bizarre. The officers traveling with them had to undertake not to publish any books about the expedition. The steamboat that transported the group on the lower reaches of the Congo had hoisted the flag of the New York Yacht Club, at the request of the publisher James Gordon Bennett Jr. The force of 389 men was greatly decimated when they finally faced Emin Pasha. As Stanley himself noted, he wore a crisp white, freshly ironed uniform and one wonders who saved whom, especially since the supplies of the “liberators” were exhausted.

Stanley barely managed to persuade Emin Pasha to come with him, but this time the shorter route, east. Unfortunately for Stanley, he could not persuade him to enter the service of Leopold; he decided to work for the Germans.

Though the expedition was far from a success, Stanley was given a triumphant welcome on his return to Europe. He has been showered with honors, has received medals from several European scientific societies and honorary doctorates from the universities of Oxford, Cambridge, Durham and Edinburgh. A reception given by the Royal Geographical Society at the Royal Albert Hall attracted 10,000 guests, including the Prince of Wales .

Marriage and retirement (1890–1904)

On July 12, 1890, Stanley married the society painter Dorothy Tennant . She had spurned him a few years earlier, but after Emin Pasha's rescue she began to write him letters. Several Stanley biographers, including Frank McLynn, believe the marriage never consummated, but the Stanleys adopted a son, Denzil Stanley, in 1896. Stanley also had a special relationship with Edward James Glave , whom he knew from his stay in Congo in the service of Leopold II and considered his foster son.

Stanley liked not being alone anymore. He only traveled to "civilized areas" where he gave lectures and presented his books. Returned from a lecture tour to Australia, he was reintroduced into England in 1892 and was a member of the House of Commons from 1895 to 1901, where he joined the Unionist Party. In October 1897, following an invitation to the opening of the Bulawayo Railway , he traveled through South Africa, visited the Transvaal Republic , the Orange Free State and Natal and met Paul Kruger in Pretoria . In 1899 he was beaten to the Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath (GCB).

Meanwhile, news of the atrocities in the Congo reached England. Edmund Dene Morel , a young man who worked in the haulage business, had discovered in the 1990s that ships from the Congo were bringing a lot of goods, mostly ivory and rubber, but that only ammunition was being carried on the way back. He started what was probably the first human rights campaign in history, published a regular newsletter and corresponded with missionaries and Congo travelers, including the writer Joseph Conrad , who provided him with information.

When Stanley died in London on May 10, 1904 , the mood had changed. The Dean of Westminster Abbey , J. Armitage Robinson , denied his request to have a funeral in Westminster Abbey at Livingstone's side. Instead , he was buried in his last home, Pirbright , Surrey . His wife had him erect a tombstone with the inscription "Henry Morton Stanley, Bula Matari, 1841–1904, Africa".

Publications

Stanley's books on Africa are very detailed. In Through the Dark Part of the World there are over a hundred drawings, including plans of African houses, plans of typical villages, drawings of battles, comparison of different African canoe paddles . Tables provide information about the air and water temperature, the depth of the various lakes, or the price of a chicken. His books often contain excerpts from his diaries, but these often have little to do with the real diaries. There, for example, he kept a book on the punishment of porters: "The two drunks sentenced to 100 lashes, then 6 months in chains."

- How I found Livingstone. Travels, adventures and discoveries in Central Africa including four months residence with Dr Livingstone , London 1872

- Coomassie and Magdala: The Story of two British Campaigns in Africa , London 1874

- My Kalulu , Prince, King, and Slave , London 1874

- Through the dark continent, or the sources of the Nile, around the great lakes of Equatorial Africa and down the Livingstone river to the Atlantic Ocean , London 1878

- Stanley's first Opinions: Portugal and the Slave Trade , Lisbon, 1883

- The Congo, and the Founding of its Free State , 1885, last published in Detroit 1970, ISBN 0-403-00288-5

- In Darkest Africa: Or the Quest, Rescue, and Retreat of Emin, Governor of Equatoria , London 1890 (Digitized: Volume 1 , Volume 2 )

- The story of Emin's rescue as told in Stanley's letters , London 1890, most recently New York 1969, ISBN 0-8371-2177-9

- My dark Compagnions and their strange stories; Slavery and the Slave Trade in Africa , 1893

- My Early Travels and Adventures in America and Asia , London 1895, ISBN 0-7156-3085-7

- Through South Africa , 1898

- Africa, its Partition and its Future , 1898

Published posthumously

- The Autobiography of Sir Henry Morton Stanley: The Making of a 19th Century Explorer , London 1909, ISBN 1-58976-010-7

- HM Stanley: Unpublished Letters , 1961

- Stanley's Dispatches to the New York Herald 1871–1872, 1874–1877 Boston 1970, edited by Norman R. Bennet

- The story of Emin's rescue as told in Stanley's letters , New York 1969, edited by J. Scott Keltie, ISBN 0-8371-2177-9

In German language

- How I found Livingstone. Travel, adventure, etc. Discoveries in Central Africa (= original title: How I found Livingstone ), Brockhaus / Reclam, Leipzig 1879; New edition: edited by Heinrich Pleticha, (= old adventurous travel reports ). 3rd edition, Edition Erdmann, Stuttgart / Vienna 1995, ISBN 3-522-60480-6 , 2012: ISBN 978-3-86539-832-1 .

- Through the dark part of the world or the sources of the Nile, traveling around the great lakes of equatorial Africa and down the Livingstone River to the Atlantic Ocean , translated from the English by C. Böttger, Leipzig 1878

- The Congo and the founding of the Congo State . Work and research. Translated from the English by H [ugo] von Wobeser. 2 volumes. FA Brockhaus, Leipzig 1885.

- In darkest Africa. Search, rescue and retreat of Emin Pascha , from the English by H. von Wobeser. Leipzig 1890

- together with A [rthur] J. Mounteney Jephson: Emin Pascha and the mutiny in Aequatoria . Nine-month stay and imprisonment in the last of the Sudan provinces. Translated from the English by H [ugo] von Wobeser. FA Brockhaus, Leipzig 1890.

- My life (2 volumes), translated from the English by Achim von Klösterlein and Gustav Meyrink. Publishing house The Reading, Munich 1911

The first edition is given.

See also

literature

In chronological order:

- Julius Löwenberg : A hero of geographic research . In: The Gazebo . Issue 7, 1878, pp. 113–116 ( full text [ Wikisource ]).

- Walter Bauer : The Black Sun. The story of Henry Morton Stanley. With illustrations by Hans Peters . Verlag Henri Nannen - Hannoversche Verlagsgesellschaft, Hanover 1948 ( Die Bunten Hefte. No. 3, 1948, ZDB -ID 2231547-0 ).

- Hans-Otto Meissner : The Congo reveals its secret. The Adventures of Henry M. Stanley. Cotta, Stuttgart 1968 (reprint: Mundus Verlag, Stuttgart 1982, ISBN 3-12-920041-X ( The adventures of world discovery 9)).

- Quirin Engasser (ed.): Great men of world history. 1000 biographies in words and pictures . Neuer Kaiser Verlag, Klagenfurt 1987, ISBN 3-7043-3065-5 , p. 441.

- P. Werner Lange : Henry Morton Stanley. His way to Africa , Verlag Neues Leben, Berlin 1990 and Edition Erdmann, Stuttgart 1990 (there as Henry Morton Stanley. The biography ).

- Frank McLynn: Stanley. The Making of an African Explorer . Oxford University Press, Oxford 1991, ISBN 0-8128-4008-9 ( Oxford lives ).

- Adam Hochschild : King Leopold's Ghost. A Story of Greed, Terror and Heroism in Colonial Africa. Houghton Mifflin et al. a., New York et al. a. 1999, ISBN 0-333-76544-3 .

- Martin Dugard: Off to Africa! Stanley, Livingstone and the search for the sources of the Nile. Piper, Munich a. a. 2005, ISBN 3-492-24407-6 ( Piper series ).

- Joachim Fritz-Vannahme: pen and whip . In: Die Zeit , No. 19/2004, “Zeitlaufte”.

- Alan Gallop: Mr Stanley, I presume ?: the life and explorations of Henry Morton Stanley . Sutton, Stroud 2004, ISBN 0-7509-3093-4 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Henry Morton Stanley in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by Henry Morton Stanley in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Newspaper article about Henry Morton Stanley in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- On the history of rubber use , with detailed explanations about the Congo

- kongo-kinshasa.de German-language website about the Congo

- Article on the establishment of the Congo Colony

- Henry Morton Stanley Archives , Royal Museum for Central Africa

Individual evidence

- ↑ Oliver Carlson: The Man Who Made News: James Gordon Bennett . Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1942, p. 386.

- ↑ Tim Jeal: Stanley: The Impossible Life of Africa's Greatest Explorer . Yale University Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-300-14223-5 , p. 435, Google Books

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Stanley, Henry Morton |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Rowlands, John (maiden name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | British-American journalist, African explorer and book author |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 28, 1841 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Denbigh , Clwyd, Wales |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 10, 1904 |

| Place of death | London |