Herbert Henry Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith (born September 12, 1852 in Morley , Yorkshire , † February 15, 1928 in Sutton Courtenay , Berkshire ), best known as H. H. Asquith, was a British Liberal Party politician and Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1908 to 1916. He previously served as Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1905. Asquith's name is primarily associated with the great social reforms of the liberal governments from 1906 to 1914 and the resulting violent clashes with the conservative opposition .

Born into a middle-class family, won Asquith a scholarship at Balliol College of University of Oxford , where he excelled. After a career as a lawyer, he ran as a candidate for the Liberal Party for a seat in the House of Commons . From 1892 to 1895 he was Home Secretary in the Gladstone and Rosebery administrations .

Acted as the coming man in his party since 1895, he finally became Prime Minister in 1908, succeeding the dying Henry Campbell-Bannerman . Under his aegis as Prime Minister fell the ongoing political disputes over the social reform projects of the Liberals and the question of self-government in Ireland ( Home Rule ). In the Parliament Act 1911 , the veto power of the traditionally conservatively dominated House of Lords was finally broken and an old-age pension and insurance against illness and disability were introduced. In terms of foreign policy, the naval race with imperial Germany was forced upon his government, and Great Britain tied itself to France in an ever closer alliance .

In August 1914, Asquith led the United Kingdom in the First World War . After increasing setbacks and military defeats, he was forced to form a coalition government with the Conservative Party in 1915 . As a result, Asquith's political star declined and he came increasingly under criticism from a largely hostile press. Successes were attributed to his inner-party rival Lloyd George , failures Asquith blamed. In late 1916 he was finally overthrown by Lloyd George and the Conservatives and led the greater part of the Liberal Party into the opposition and in the following years into political insignificance.

Origin and early career

Asquith was born as the second son of Joseph Dixon Asquith and his wife Emily into a middle-class dissenter family. At a young age he was called "Herbert" in the family, but his second wife called him "Henry". He was always called H. H. Asquith in public. His biographer Roy Jenkins writes: "There are few people of national importance whose first names were so little known to the public".

His father, employed in the wool trade, died prematurely when Asquith was only eight years old; Because of this early death, in contrast to his mother, he had hardly any formative influence on Asquith. The family moved to Huddersfield after their father's death , where they were supported by Asquith's uncle, William Willans. This made sure that Asquith could attend Huddersfield New College. After Willans passed away, the family moved to Sussex and was supported by John Willans. However, when John Willans moved to Yorkshire for business, the family was separated and moved to different families.

Asquith and his brother attended the City of London School, where Asquith excelled , particularly in English and Classical Studies . He remained connected to the school principal Edwin Abbott Abbott throughout his life and said that he owed him deeply. However, he said that he had never had a student who owed him less and so much of his own abilities. Asquith gained a scholarship at Balliol College of Oxford University . There he exceeded all expectations and performed brilliantly; the progressive liberal views of the tutor Thomas Hill Green , which exerted great influence in Oxford, also influenced Asquith's political views. Shortly after his arrival, he began speaking at the Oxford Union Debating Club. Towards the end of his time at Oxford, he also became chairman of an influential student association. He completed his studies with top marks in Literae humaniores . Balliol remained his spiritual home all his life. In the opinion of his contemporaries, he embodied like no other the saying, coined by himself, that the people of Balliol had "the calm awareness of effortless superiority".

After graduating, he became a lawyer and was admitted to the court in 1876. This activity made him prosperous in the early 1880s.

family

In 1877 Asquith married Helen Kelsall Melland, the daughter of a doctor from Manchester . The marriage had four sons and a daughter before Helen died of typhus in the summer of 1891 while the family was vacationing in Scotland. The only daughter from this marriage, Violet Asquith (later Violet Bonham-Carter ) shared her father's political interests and began to be politically active for the Liberal Party in the 1920s. She later became a respected writer. In 1915 she married her father's private secretary; In 1964 she was awarded a title of nobility for life. The eldest son Raymond fell on the Somme in 1916, and so the title of nobility passed to his only son Julian (born in 1916, a few months before his father's death). The current title holder is Asquith's great-grandson Raymond Asquith, 3rd Earl of Oxford and Asquith . Another son, Cyril , became Law Lord (member of the House of Lords with special legal responsibility). One of two other sons was the poet Herbert Asquith, who is often mistaken for his father.

After the death of his first wife, Asquith bought a house in Surrey and hired nannies and housekeeping for his children while he himself worked in London during the work weeks. In 1894, Asquith married Emma Alice Margaret Tennant (1864–1945), known as "Margot", whom he had courted for several months. She was the daughter of Sir Charles Clow Tennant, 1st Baronet, a Liberal MP. The opinionated and extroverted Margot Asquith was in many ways the opposite of Asquith's first wife. This marriage resulted in five children, two of whom survived childhood: Elizabeth (1897–1945; later Princess Antoine Bibesco), a writer, and Anthony (1902–1968), later film director. Margot's relationship with the daughter from her first marriage, Violet, was notoriously strained.

His other descendants include actress Helena Bonham Carter and the wife of former Liberal Party leader Jo Grimond .

Start of political career

In order to supplement his income, Asquith began in 1876 to write articles for the Spectator , which was then rather liberal. With the beginning of the 1880s he became more and more interested in politics. In 1885 his close friend Richard Haldane was elected to the House of Commons ; In the new elections due in 1886 , Haldane Asquith proposed to run as a Liberal candidate for the constituency of East Fife, since the local Liberal MP no longer supported the Liberal government, but Joseph Chamberlain's independent unionists. Although he had no ties to Scotland, Asquith was confirmed by the local Liberal Party organization. Asquith immediately succeeded in entering the House of Commons for this secluded constituency, which had been firmly in liberal hands since the Great Reform Act of 1832 . Asquith soon formed a close friendship with Haldane and Edward Gray , another young MP.

Asquith's political career coincided with increasing tensions in Britain's political fabric. In addition, the country experienced a change of times; If the 19th century had been politically dominated by the Liberals for long stretches, Gladstone's advocacy of the Irish Home Rule now split the Liberal Party and ended liberal dominance in the electorate. A group of liberals who saw Gladstone's initiative as a threat to the union between Great Britain and Ireland , which had existed since 1800 , turned away from the liberals and, as liberal unionists, formed an independent parliamentary group in the lower house. In association with the Conservative Party, they overturned Gladstone's Irish self-government bill in 1886. Their gradual rapprochement with the Conservatives put a heavy burden on the Liberal Party and allowed the Conservatives a period of dominance under their leader Salisbury . The consequences were particularly severe in the House of Lords , where the great mass of liberal peers switched sides and the balance of power was sustained and drastically influenced in favor of the conservatives. The discussion about “Home Rule” caused considerable tension between supporters and Opponents.

Against this background, Asquith gave his first speech in the House of Commons in March 1887; During the remainder of the parliamentary session he occasionally spoke up there, mostly on Irish issues, which were the dominant political issue and which for Liberal Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone became more and more of a central issue and an obsessive personal agenda.

Asquith's potential was quickly noticed by Gladstone, who invited him over and gave him political advice. Gladstone won his first post in 1892, when he made Asquith Home Secretary in his fourth cabinet . While other new members of parliament had to content themselves with posts as simple junior ministers outside the cabinet, this made him by far the most highly promoted politician of his generation. He was also admitted to the Privy Council . In 1893, as Home Secretary, he had to cope with a coal workers' strike in Yorkshire, which led to violent clashes and riots. Since the local police had lost control, he sent troops to the area to maintain public order; Local magistrates shortly afterwards had the Riot Act read publicly during a demonstration in Featherstone and the soldiers present were shot into the crowd, whereupon two protesters died. Asquith therefore set up an independent commission to deal with the handling of the matter by those responsible. Nonetheless, this event haunted him for years and he was occasionally confronted with this episode by protesters during election campaign appearances, who interrupted his speeches with shouts for Featherstone. On his initiative, a bill was passed aimed at mine operators and intended to make them liable for accidents involving their employees on the job. However, the law was rejected by the House of Lords.

In 1894 the very old Gladstone resigned; he himself saw Sir William Harcourt as his successor, but the Liberals opted for Lord Rosebery - also because of Queen Victoria's dislike for the former. The next phase of liberal government was marked by an uncertain balancing act. Hartington joined Rosebery's government as the new Chancellor of the Exchequer (Treasury Secretary) only in return for far-reaching concessions . As leader of the liberal ruling faction in the lower house , he repeatedly undermined the leadership of Rosebery, who sat in the upper house. Both were completely at odds over questions of foreign and financial policy. In the course of the Armenian crisis , Gladstone also came back from his retirement and undermined Rosebery by energetically demanding - as in 1877/1878 - a military intervention by Great Britain against the Ottoman Empire.

Asquith instinctively leaned toward Rosebery in this yearlong internal party civil war; of Harcourt, he said: "To tell the bare truth, [he] was an almost impossible colleague and would have become an entirely impossible boss."

In 1895 the Liberal Party lost the general election and went into opposition. The liberals were increasingly paralyzed by their internal power struggles. Even after the defeat there was no agreement between Rosebery, as leader of the Liberals in the upper house , and Harcourt, as the liberal faction leader in the lower house. However, both resigned in 1896 and 1898 respectively. Asquith was asked by several party friends to run for Liberal opposition leader in the House of Commons, but turned it down because he could not afford to give up his barrister income for the unpaid full-time post of opposition leader. Within the Liberal Party, he became the leader of the free trade wing turned against Joseph Chamberlain , which contradicted his tariff reform plans. He also stood up for imperialism and the British Empire, and after some hesitation he supported Irish self-government.

Relugas Compact

In the course of 1905 it became clear that the Conservative - Unionist government of Arthur Balfour , who was deeply divided on the free trade issue, no longer continue in office would be able to keep. At the same time, several candidates for leading cabinet positions in the liberal opposition began to position themselves, as Henry Campbell-Bannerman was seen more as a placeholder and a temporary solution. Asquith, Edward Gray and Richard Haldane met in September 1905 on vacation in Scotland, where they made agreements in the " Relugas Compact " on the conditions under which they would be ready to enter a new government. Asquith would be Chancellor of the Exchequer, Haldane Lord Chancellor, and Gray Foreign Secretary. The Leader of the House of Lords Liberals and potential Prime Minister, Lord Spencer , left the follow-up discussion in October when he suffered a severe stroke. This paved the way for Campbell-Bannerman to succeed him. On December 4, 1905, Balfour finally resigned (as the last Prime Minister to date) without having previously lost an election and handed over the business of government to the liberal opposition. Campbell-Bannerman offered Asquith the office of Chancellor of the Exchequer, which he immediately accepted. Asquith became Chancellor of the Exchequer in the Campbell-Bannerman government. Campbell-Bannerman definitely refused Haldane's request to move to the House of Lords. The attempt by Asquith, Gray and Haldane to "push" Campbell-Bannerman into the House of Lords in accordance with the agreement reached in order to win the leadership of the Liberal faction in the House of Commons in addition to his position as Chancellor of the Exchequer failed. Gray and Haldane then announced their willingness to join the cabinet.

The Liberals immediately called new elections to be confirmed in office. In the elections of 1906 (which continued for several weeks) the Liberals achieved a clear landslide victory, while the Conservatives suffered significant losses. The composition of the Liberal lower house group changed considerably in this election - lawyers and business people who had previously been trained at a public school and later studied at Oxford or Cambridge were now much more represented. This change represented Asquith first of all.

Chancellor of the Exchequer

In the late Victorian era , as a result of numerous social studies of poverty in parts of society, a reform movement developed which, on the literary side, for example, drastically described the effects of poverty. The documentary work by Charles Booth, for example, on the widespread poverty in parts of London raised public awareness of problems such as old-age and child poverty. In politics, there was an increasing discussion among the liberals about the role of the state and the need to counter the grievances with the help of political initiatives. This has now been echoed in an extensive reform and legislative program that the Liberals tried to implement. However, they were blocked by the conservatively dominated House of Lords, which vetoed most of the legislative proposals.

As Chancellor of the Exchequer, Asquith strongly advocated the principle of free trade , albeit less aggressively and visibly than Secretary of Commerce David Lloyd George . He also tried to reduce general expenses. The first budget he presented was not very significant in the eyes of the contemporary press and his biographers, as the new elections and the short training period for the cabinet left little room for personal accents. When he presented the budget to the House of Commons, he therefore stated that he had little more than four months to review the situation, but that he was presenting the finances of a whole year, for which he was therefore hardly responsible. In his second budget from 1907, Asquith dared to take a major innovative step and introduced - for the first time in British history - a differentiated income tax rate for different income brackets. In addition, he made a distinction in his budget for the first time between earned income and income from assets. He also increased the inheritance tax. At the same time, on the other hand, he lowered taxes on selected natural products such as sugar, which was supposed to benefit the poor and the poor.

During this time, Asquith was increasingly the executor of the Prime Minister in the House of Commons, where he repeatedly fought heavy speech duels with the leading representatives of the opposition. Prime Minister Campbell-Bannerman, long in ill health, suffered three heart attacks during 1907. Short cures did not bring about any improvement. Asquith took his place in this phase. In February 1908, Campbell-Bannerman suffered another heart attack. Finally, already slowly dying, he resigned on April 1, 1908 for health reasons. King Edward VII immediately sent for Asquith, who then traveled to Biarritz, where Edward VII spent his usual vacation to kiss the monarch's hand and become the new Prime Minister.

Asquith as Prime Minister

Cabinet reshuffle

On his return, Asquith reshuffled the cabinet in several positions; after briefly flirting with keeping the office of Chancellor of the Exchequer, he appointed Lloyd George to succeed him in the Treasury. Since he and Foreign Minister Gray were counted among the Liberal Imperialists, the promotion served to balance the factions within the party. The young Winston Churchill became President of the Board of Trade in his place . Lord Tweedmouth , previously First Lord of the Admiralty , was deported to the post of Lord President of the Council to install Reginald McKenna as the new First Lord of the Admiralty. Lord Elgin was dismissed as Colonial Minister and the Earl of Portsmouth as Undersecretary in the War Department. The Earl of Crewe , who is considered moderate , became the new colonial minister and at the same time Leader of the House of Lords . With Richard Haldane, John Morley and Augustine Birrell, Asquith's cabinet brought together high- profile intellectuals, and with the promotions of Lloyd George to Chancellor of the Exchequer and Winston Churchill, who took over Lloyd George's old position, two emerging political figures were integrated who had already worked as rhetorical heavyweights were considered. Asquith recognized both of them as valuable assets and treated them kindly, but always showed them intellectual snobbery as a former Balliol graduate. In a short time Asquith developed a close relationship with Churchill (but not with Lloyd George) and, despite or because of the age difference, spent a lot of time with him privately; in October 1914 he wrote to Venetia Stanley: “I can't help but be fond of him; he is so resourceful and courageous: two qualities that I value most. ”The only cabinet colleague who could match Churchill in this regard was Reginald McKenna. In a letter to Venetia Stanley, Asquith put both of them at the forefront as far as services to the Cabinet were concerned. However, according to Asquith and Churchill biographer Roy Jenkins , this list, with Crewe at number one and McKenna at number three, shows in a somewhat depressing way how not causing trouble for the prime minister is a quick route to ministerial esteem and cabinet merits.

Style as prime minister

As Prime Minister Asquith moderated the internal cabinet discussions as a primus inter pares in the style of a chairman; He usually brought up the issue to be discussed and then asked for individual opinions. In the end he recapitulated the content and the outcome of a debate. This collegial, moderating style of leadership established itself permanently and became the ideal of the prime minister's leadership of the cabinet; At the latest with the beginning of Margaret Thatcher's government , which led the discussions aggressively and preferred a combative, sometimes rude tone, this model became obsolete. In his 1937 book Great Contemporaries , Churchill retrospectively described Asquith's style at Cabinet meetings: “In the Cabinet he was remarkably quiet. He never even spoke a word when it wasn't necessary. He sat as the great arbiter he was and listened to the arguments of each side with trained calm, throwing in a question or a short comment here and there, questioning or concise, that brought the matter in a direction towards a goal, which he wished to achieve. ”Similarly, Lloyd George said of Asquith in 1912:“ He is a great man. He never initiates anything, but he's a great referee. He wipes away all the little dots and purposefully goes to the heart of it all. I would rather discuss a big undertaking with him than with anyone else. "

After the cabinet reached a joint decision, Asquith held fast to it. He usually gave his cabinet members a great deal of freedom in their work and refused to rule over their portfolios. He usually held cabinet meetings once a week. After each meeting, he informed the king of the results in handwritten minutes, usually downplaying internal cabinet disputes, conforming to the king's inclinations and concentrating on foreign policy.

As Prime Minister, Asquith kept the life and work rhythm that he had led as a lawyer and saved the weekend for his private life, which he spent mainly in the large country houses of the upper classes as well as in The Wharf , a country house bought in 1911 in Sutton Courtenay . There he usually spent his free time playing bridge, golf and reading. He stuck to this lifestyle from 1914 onwards in times of war, which increasingly caused displeasure and criticism among his followers.

He devoted a particularly large amount of time to intensive correspondence with an inner circle of confidants. Asquith, who generally enjoyed the company of younger people, met Venetia Stanley , a friend of his daughter Violet, in 1912 . He soon maintained close contact with her. Although Asquith's letters (he burned the answers) are often written with affectionate salutations, there is general consensus that the relationship was most likely purely platonic in nature and that Asquith served more as an outlet for his everyday political worries, as Venetia Stanley gave him one Kind of calm, listening empathy that his wife Margot, overly sensitive and nervous, did not give. After she decided to marry Edwin Montagu, the acquaintance ended abruptly. However, Asquith soon found pen pals in Katherine Scott (the widow of the Antarctic explorer) and Venetia Stanley's sister, with whom he led a similarly intensive correspondence.

Continuation of the liberal welfare program

Domestically, Asquith's government continued the line begun under Campbell-Bannerman and in 1908 launched an extensive welfare program with state pensions. The Old-Age Pensions Act 1908 introduced state pensions for people over the age of 70 who had little income. Furthermore, a juvenile court was introduced in the 1908 Children's Act to separate cases of children who have committed offenses from the existing normal justice system. The law also included several reforms that applied to child and youth protection. For example, the sale of cigarettes to children under the age of 16 was banned, measures were taken to protect underage witnesses in court, and mandatory registration for newborns was introduced. For this purpose, Chancellor of the Exchequer Lloyd George worked out health insurance for workers who were below a certain income limit (£ 160 per year). Furthermore, a temporary unemployment benefit was created for part of the workforce. These two changes finally became part of the legislation in 1911 in the National Insurance Act 1911 . To this end, a salary was introduced for the first time in 1911 for members of the lower house in order to open the lower house to all classes of the population. With these laws and reforms, Asquith's liberal government created a cornerstone of the modern welfare state.

These reforms were problematic due to their financial implications - parallel to the additional expenditure for the welfare program, ever larger sums had to be spent on the maintenance and expansion of the Royal Navy. However, the additional financial burden was not offset by a significant increase in income. The welfare program was therefore controversial and was fought hard by the conservative opposition. This suggested tariffs as an alternative in order to achieve higher tax revenues, which would have meant a departure from the prevailing dogma of free trade.

Conflict with the House of Lords

The Conservatives used their traditional majority in the House of Lords and blocked liberal legislation. For this reason, reviled by Lloyd George as " Balfour's poodle ", the House of Lords rejected most of the Liberal laws back to the House of Commons for party-political reasons. The conflict came to a head when Chancellor of the Exchequer Lloyd George presented a provocative "People's Budget" in 1909, which was supposed to be financed with taxes on land, income and luxury goods. Due to the conservative blockade in the upper house, the liberal cabinet had decided to circumvent this with a trick; traditionally, financial and budgetary issues were the very domain of the lower house and were not challenged by the upper house. Traditionally, the Lords had not interfered in budget issues. The Liberals therefore bundled all of their legislative proposals into one large law, the annual draft budget. The Conservatives, determined not to let the draft pass, challenged the law in the House of Commons at every stage and, at every opportunity, forced the Speaker to divide the House . This slowed down normal parliamentary operations and the government had to extend the parliamentary session to the usual summer break and beyond. Most of the burden was carried by Chancellor of the Exchequer Lloyd George, who spent most of the nights in the House of Commons at the late sessions, defending the law he had introduced. After the law was passed through the House of Commons in early November 1909, the Conservatives, led by Balfour and Lord Lansdowne (leader of the Conservatives in the House of Lords), despite some resistance from their party, used the large Conservative majority in the House of Lords to block it. So there was a constitutional crisis; Asquith reacted immediately to this challenge and called new elections on December 2nd. He started the election campaign with a grand appearance in front of 10,000 people in the Albert Hall; In a celebrated speech he called for the people to have the right to see their decisions implemented by their elected representatives. In addition, he openly announced that he would give up the reluctance of the Liberal Party on the Home Rule question that had existed since 1906.

From the new elections in January 1910 , the Liberals emerged clearly weakened and, after the formation of a minority government, were henceforth dependent on the support of the Irish Parliamentary Party . To do this, one was still dependent on the help of the Labor Party; With this, a loose electoral alliance had existed for years in the individual constituencies in order to support the most promising candidate against the local conservative candidate. Although the Lords have now approved the budget after making some concessions, this created a new problem as the IPP made their support dependent on a new draft law on Irish self-government, which was rejected by the Conservatives.

One possibility with great explosive power in this situation was to induce King Edward VII to threaten to fill the upper house with newly appointed liberal peers and thus to change the majority in the upper house in favor of the liberals by pushing peers . These would be able to override the previous veto of the Lords. The king informed him, however, that in his view the result of the lower house election was inconclusive and that he would wait for another lower house election. When the Conservatives remained adamant in the spring of 1910, Asquith tried step by step to obtain a binding promise from the king. King Edward was deeply reluctant to do so and was suspicious of the various constitutional proposals for reforming the House of Lords that were now circulating in Westminster. However, he allowed himself to be persuaded to warn the House of Lords of "serious consequences" without specifying them in more detail. Completely surprisingly, he died in May 1910; Asquith got the news on board the Admiral's yacht in the Bay of Biscay en route to a vacation in Spain and Portugal and immediately turned back. His son, the new King George V , was politically inexperienced and had not been brought up to become the new monarch in his career. He hesitated to carry out a drastic attack on the nobility as the first official act in his new role. Asquith therefore first tried to reach an agreement or a compromise in already arranged informal talks with the leading conservatives.

In the talks that followed, which lasted six months, the Liberals were represented by Asquith, Lloyd George, Crewe and Birrell, the Conservatives by Balfour and Lansdowne and Austen Chamberlain and Cawdor . Asquith and Lloyd George were just as willing to compromise as Balfour on the other side. However, the conservative side was not dominated by Balfour, but by Lansdowne, who proved to be as pessimistic as he was stubborn throughout the course of the talks. With all the compromise formulas proposed, Lansdowne already had possible implications for the smoldering Home Rule question in mind, where he had been an absolute hardliner since the 1880s and under no circumstances did he want to give in. With the support of Cawdor, he was more willing to let the conference calls fail than to make Home Rule in any way more likely. Lloyd George's proposal (to Asquith's annoyance) to form a coalition of conservatives and liberals also quickly fizzled out. On November 10, 1910, the talks broke down. At a cabinet meeting it was decided to dissolve parliament before Christmas and call a new general election. Asquith went to Norfolk the following day to inform the King of the new situation at Sandringham House .

Asquith, who could not be sure of the king's attitude, behaved vaguely and ambiguously with the politically inexperienced king in the talks and avoided urging him to accept; With this tactic he finally managed to gradually move the king to an initially purely informal promise. A few days later, Asquith and the cabinet also asked for a formal commitment, which should initially be kept confidential. The king, still torn, received conflicting advice from his two secretaries, Francis Knollys and Arthur Bigge . Bigge wanted to encourage the king to refuse Asquith guarantees and, if necessary, to entrust Balfour with the formation of a new government if the liberal government resigned. Knollys, on the other hand, leaned toward Asquith's position, leaving the king in the belief that Balfour would not form a minority government. Under this impression, King George finally gave his consent and binding commitments before the second election in December 1910.

At the same time, Asquith kept the extent of the talks with the king to himself and kept the conservative opposition in the dark. Relying on the fact that the Liberal government would never get the king's approval for far-reaching measures, the Conservative Lords publicly insisted on a tough stance. On the Liberal side, Asquith dominated the Liberal election campaign and made speeches in all parts of the country. As a result of the general election, the balance of power in the lower house remained essentially unchanged - the Liberals and the Conservatives were evenly balanced, with the Liberals able to continue to govern with the support of Labor and the IPP. With the king's threat now made public, the liberal government was able to curtail the power of the upper house with the parliamentary law of 1911 . A group of younger Conservatives around FE Smith and Lord Hugh Cecil responded by shouting Asquith down for half an hour during his opening speech, forcing him to sit back unheard. Faced with the prospect that the House of Lords would win a liberal majority through mass ennoblement, a group of conservative peers led by George Nathaniel Curzon voted with the liberal minority so that the law could pass the House of Lords. Indeed, this law broke the power of the House of Lords. The Lords could now delay a law passed by the House of Commons, but no longer prevent it entirely.

This defeat sparked an intra-party power struggle in the Conservative Party, which eventually led the party leader Arthur Balfour, who was viewed as too hesitant and moderate, to resign. At a meeting at the Conservative Carlton Club , Conservative MPs elected Andrew Bonar Law as their new chairman in the House of Commons. In contrast to Balfour, he used a tough, confrontational style in his speeches in the House of Commons and attacked the Liberals sharply. Asquith, who respected the intellectual Balfour very much and liked him personally, on the other hand, had little regard for the businessman Bonar Law and had little respect for him.

Strikes, suffragettes and the Marconi scandal

Despite the reforms introduced, Great Britain was increasingly shaken by labor disputes; a great wave of strikes broke out especially between 1910 and 1912. In addition, there were various public actions by the suffragettes who wanted to enforce women's suffrage , some of which were militant. Within the Liberal Party there was a large group of lower house members who advocated women's suffrage. Asquith himself was attacked by a group of militant Sufragettes while playing golf while on vacation in Lossiemouth, Scotland, and had to fight them together with his daughter Violet. On the way to Stirling, Scotland, where he was to inaugurate a memorial to his predecessor Campbell-Bannerman, he was also attacked by sufragettes (with a bull whip, among others). These and similar sensational actions by the suffragettes (like that of Emily Davison , who threw herself in front of George V's horse at the Epsom Derby in 1913, or the destruction of windows in the shopping district of London's West End) had the opposite effect at Asquith, which increased their cause opposed and stiffened in his resistance. In 1917, after already being in opposition, he finally changed his mind on the matter.

The Marconi scandal of 1912/1913 was a severe blow to the integrity of the government. The director of the British Marconi company, Godfrey Isaacs, had decided to expand the volume of the American company through a capital increase and the issue of new shares and a block of shares in the American Marconi company (which was legally formally independent, but was majority-owned by the British company was controlled) to his two brothers, Harry and Rufus Isaacs , at a price of ₤ 2 (below the market value of ₤ 3). Rufus Isaacs, Minister in Government, then sold part of his package to Lloyd George and Liberal Chief Whip Alexander Murray, 1st Baron Murray of Elibank , at purchase price. As soon as the new shares were listed on the stock exchange and the price rose to 4 ₤, both ministers sold their shares. Shortly thereafter, however, everyone began to buy new shares, some for the Liberal Party Fund. The prices fell and everyone made losses overall. Rumors soon began to circulate in the City and in the gentlemen's clubs of London that those involved had made fantastic profits with their knowledge as ministers. In addition, the matter was soon exploited by the press; especially the magazine Eye Witness , directed by Hilaire Belloc , attacked the ministers. Asquith was briefed by Isaacs but did not take the matter seriously. Rather than explain and apologize, Isaacs and Lloyd George denied having acquired shares in "the Marconi company" during a debate in the House of Commons, but their carefully crafted statement referred only to the British company. The Conservatives soon found out what was going on and tried to capitalize on the matter. Asquith admitted to the king that the behavior of the ministers involved around Lloyd George was difficult to justify. Nonetheless, he stood before his ailing colleagues and vigorously defended them in the House of Commons. For John Campbell, this was a model example of a prime minister who successfully stands in front of his colleagues instead of simply firing them.

The parliamentary committee appointed came to an ambiguous result; the liberals involved acquitted Lloyd George and Rufus Isaacs of all allegations, the conservatives involved both also acquitted of the allegations of corruption, but criticized a "serious incorrectness" and disrespect for parliament, since both had not told the full truth in previous debates would have.

The denationalization of the Welsh Church was another important liberal reform project. Since only a minority of the population in Wales belonged to the Anglican Church , dissenters and non-conformists raised the demand that the Welsh Anglican Church should lose its status as a state church. Asquith had already faced this problem as Home Secretary in 1893 and pursued it without great enthusiasm, but the corresponding law had also been rejected by the Conservative Lords. The other attempts of the Liberals after 1905 also got stuck in the House of Lords. In 1914, after a two-year veto, the law could pass the House of Lords. An enactment failed because of the outbreak of war.

Home Rule

After the two general elections in 1910, the Liberals had to rely on the support of Labor and the Irish Nationalists (IPP) around John Redmond because of their reduced majority . They wanted to introduce Irish self-government in Ireland ( Home Rule ). On the one hand, the Anglo-Irish lords, who owned extensive land in Ireland, resisted this concern. On the other hand, the Scottish Protestant population, who for centuries had made up the vast majority in most of the counties in the Northern Irish province of Ulster , also opposed it . In the case of self-government in Ireland, the local population claimed an independent solution, i.e. a separation of Ulster from the rest of Ireland. Both the liberals and the Irish supporters of Irish self-government did not want to accept this for economic reasons - without the wealth generated from the industrialized Belfast and the surrounding area, the rest of Ireland seemed doomed to fail economically. The price for continuing to support the IPP was the third Irish Self-Government Act which Asquith finally introduced in early April 1912. Even if some ministers like Churchill and Lloyd refused to ignore George Ulster, they had been overruled internally in the cabinet.

For parts of the conservative opposition around their party leader Bonar Law, Ulster was a passionate affair in which they did not want to give in at any price. The question of Irish self-determination therefore led to a renewed escalation of the political conflict and quickly overshadowed all other items on the day. Home Rule, in the words of Robert Blake, represented a growing obsession with parliamentary life that has never been matched before or after. Bonar Law responded to Asquith's announcement in the House of Commons with a hostile and sharp reply. Independently of this, the strongest Home Rule opponents around Sir Edward Carson mobilized an extra-parliamentary opposition, which initially found expression through public demonstrations and protests. For this purpose lodges and “clubs” were founded, which took on paramilitary lines, prepared themselves for armed resistance and then culminated in 1913 in the establishment of the Ulster Volunteer Force . In direct response to Asquith's bill in the House of Commons, a large rally was held in Belfast, Northern Ireland on Easter Tuesday 1912, attended by 100,000 Irish Unionists who marched in military formation.

As expected, the House of Lords rejected the Home Rule. However, after being rejected twice by the House of Lords, it could happen in early 1914 without the consent of the Lords. Asquith's efforts at Irish self-government now nearly resulted in the outbreak of civil war in Northern Ireland , where Carson had already made arrangements to establish a Provisional Government and thousands of volunteers armed themselves. The army's support to enforce the law also appeared questionable after the Curragh incident : when Secretary of War J. E. B. Seely ordered the army to move troops from the Curragh army camp to Ulster in order to bring the province under military control, they refused most of the officers involved and submitted their resignation to avoid a possible confrontation with the Ulster loyalists. After the incident became known, the Conservatives in the House of Commons accused Seely and Churchill of having intended a military escalation with the order. Seely then had to resign and Asquith temporarily took over the affairs of the Minister of War. The entry into force of the Home Rule and possible subsequent implications were ultimately prevented by the beginning of the First World War in the summer of 1914.

Foreign policy

During his time as prime minister, Asquith focused primarily on domestic political issues. He left foreign policy largely to the Foreign Office and Secretary of State Sir Edward Gray, with whom he had long enjoyed a friendly understanding and with whom he broadly agreed on foreign policy views. Stephen Bates sees a paradox in Asquith's passivity, because - in contrast to Gray - he regularly spent his holidays abroad, for example on the French Riviera and sometimes in Germany. Still, he made no effort to meet with his foreign counterparts or to exert any substantial influence on foreign policy. For his part, Gray systematically shielded foreign policy from the Cabinet and the House of Commons as much as possible. The Asquith government inherited from its two previous governments the introduced equalization policy with republican France , which Gray continued and expanded. He had already come to the conclusion earlier that the German Empire was an international troublemaker and was striving for a hegemonic role; In 1902 he had expressed himself for the first time that Great Britain should orient itself against Germany.

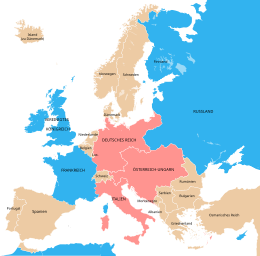

When the Liberals came to power in 1905, they had made it their declared goal to reduce "the gigantic armaments expenditure" of their predecessors. As Chancellor of the Exchequer, Asquith had made an effort to limit spending on the Royal Navy. However, after 1908, Great Britain was increasingly drawn into an expensive race in naval armaments with the German Empire. When the Liberal came to power in 1905, grants to the Royal Navy were £ 30 million, a fifth of the total annual expenditure. As a result of the general naval competition, these expenses rose again. In Great Britain, the so-called Naval Scare occurred in 1909 , which at times led to fear of invasion out of concern about the danger of the German naval armament. In addition, there were periodic press wars between the British and German press until 1912 (when there was a period of calm until 1914), which tried to heat up the public mood in both countries. These press campaigns, launched on the British side by the Northcliffe press in particular , often put an additional burden on the Liberal government.

Parallel to the deterioration in relations with Germany, Great Britain tied itself increasingly closely to France - also at Grey's instigation - especially after the Second Morocco Crisis . It was only during the Second Moroccan Crisis that Asquith was informed of the extent of the Anglo-French military talks, which Gray and the responsible military officers had kept to themselves until then. Asquith expressed concern that France would therefore take British aid into account in any war. However, Gray convinced him that these talks should continue. At the same time, from 1907, there was a settlement with Tsarist Russia. Informal negotiations with Germany on a naval agreement, which was supposed to limit the costly building of a fleet, failed in 1912, as Germany demanded a British guarantee of neutrality in return in the event of war. A dismayed Asquith wrote to Gray that, from his point of view, the negotiations were doomed to failure: “I confess that I have increasing doubts about the wisdom to continue these negotiations. Nothing less than an unconditional guarantee of neutrality on our part meets your requirements. And even for this, Germany is not making a firm or solid counter-offer in return. "

Unlike in the hotly contested field of domestic policy, these guidelines of liberal foreign policy were very much supported by the conservative opposition, which saw Grey's work as a continuation of its own policy. The Conservative Chief Whip Lord Balcarres also stated in 1912 that “Gray had been supported for six years on the condition that he continued the Anglo-French Entente which Lord Lansdowne had created and the Anglo-Russian Entente [complete] who had paved the way for Lord Lansdowne. "

Asquith in the July Crisis, 1914

In the July crisis , Asquith initially concentrated entirely on the worsening Home Rule crisis and remained waiting; as in previous years, he left foreign policy to his longtime friend and Secretary of State Edward Gray. In the course of the July crisis, Asquith came to the conclusion that a war between the major European powers was becoming more and more likely, but did not see Great Britain as an active participant. On July 24, 1914, Asquith wrote to his confidante Venetia Stanley that he saw no reason for Great Britain to participate actively in the increasingly probable war: “We are within recognizable, or at least conceivable, range of a real Armageddon, which Ulster and the Nationalist volunteers on her will reduce true size measure. Fortunately, there is no reason why we should be anything other than mere spectators. "

As soon as it became clear that the German Reich wanted to occupy Belgium and attack France, its attitude gradually changed. A strong group within the cabinet was initially against an intervention, but after the German ultimatums to Russia and Belgium , Asquith tended to join Grey's position, who wanted to maintain the Entente with France and therefore advocated entering the war. At a cabinet discussion on the evening of July 29, 1914, Asquith (along with Haldane, Churchill and Crewe ) already supported Grey's demand for a promise to support France; however, the clear majority in the cabinet firmly opposed this. This constellation within the cabinet had not changed on July 31. Asquith estimated that roughly three-quarters of his parliamentary group were in favor of "absolute non-intervention at all costs." After the undecided cabinet meeting on August 1, Asquith gave a letter to Venetia Stanley, giving insights into the deeply divided position of the cabinet: John Morley and John Simon, as leaders of the anti-interventionist group, would demand an immediate declaration that Britain should "under no circumstances" intervene . Churchill, on the other hand, was "very bellicose" and demanded an immediate mobilization of the British armed forces. Gray would resign if the majority of the cabinet would decide to be neutral, Haldane was very "diffuse and nebulous". He also gave insights into his personal decision-making process: “There is a strong group, supported by Ll George, Morley and Harcourt , who are against any kind of intervention. Gray will never agree to this and I will not part with him. ”That same evening, Asquith Churchill implicitly gave his consent to the mobilization of the British fleet.

In two extraordinary cabinet meetings on August 2, Asquith secured the support of the cabinet, from which only two ministers resigned when Britain entered the war. On the morning of the day Asquith listed 6 points in a memorandum which he passed on to the king, his cabinet colleagues and the opposition leaders, four of which spoke in favor of entering the war and two at least not against entering into the war. At a morning cabinet meeting, he and Gray initially achieved a partial change of opinion when the Cabinet authorized Gray to promise France that the British Royal Navy would intervene in favor of France in the event of an impending German attack on France's coast. On the evening of the same day, the cabinet agreed that a “substantial violation” of Belgian neutrality would oblige Great Britain to act. The two leaders of the non-interventionist wing, John Morley and John Elliot Burns , then resigned.

First World War

The beginning of the war initially led to a standstill agreement in party politics to demonstrate national unity. The Conservatives referred to this as "patriotic opposition". At the beginning of the war, Asquith's government reactivated Field Marshal Herbert Kitchener , who was extremely popular in the country, and installed him as Minister of War. This quickly began to recruit a mass army to expand the numerically small British Expeditionary Force. Just like most other politicians, Asquith initially believed in a short war, which on the British side would mainly involve the use of the superior Royal Navy and only require a small British expeditionary force. However, by the end of 1914 at the latest it became clear that the war would last longer and that a large mass army would also be necessary. This became increasingly a burden for the Liberal Party. Traditionally, the liberals were opposed to issues such as general conscription and the censorship that became necessary in times of war. Instead of compulsory military service, a voluntary system for recruitment was created in 1914, but from 1915 onwards it no longer provided the necessary numerical requirements for the Western Front. At the end of November 1914 a council of war was set up, which in practice quickly became the decisive political decision-making body and whose decisions were only subsequently submitted to the cabinet (by Asquith). Asquith convened this council of war only very irregularly, a measure which led to a considerable concentration of power in the hands of a few men and in practice meant that the actual warfare was largely in the hands of Prime Minister Asquith, Minister of War Kitchener and the First Lord of the Admiralty Churchill was lying.

As the war continued, the party-political standstill agreement between Liberals and Tories increasingly came up against its limits. War Secretary Kitchener was perceived as hesitant and indecisive and turned out to be more and more of a liability. Above all, the "Dardanelles strategy" operated by Winston Churchill with the aim of pushing the Ottoman Empire out of the war and thus creating a safe sea route to Russia's eastern ally was extremely controversial. This dispute was in the context of a more far-reaching fundamental conflict between “Westerners” (who were looking for a victory on the Western Front against the German army) and “Easterners” (who initially wanted to eliminate Germany's allies and therefore the main focus on the other, mainly eastern, theaters of war put) conditionally. Asquith himself was moderating neutral on this issue, but was basically one of the “Westerners”. The fatal and costly Battle of Gallipoli resulting from the Dardanelles offensive had led to violent conflicts. A disgusted Asquith then wrote to Kitchener: "I have read enough to convince myself that the generals and staff involved in Suvla should be brought to trial and dismissed from the army."

The resignation of First Sea Lord John Arbuthnot Fisher as a result of disagreements with Churchill created a cabinet crisis. After a split in the Cabinet, through the " ammunition crisis " ( Shell Crisis triggered) the bad course of the Gallipoli campaign as well as the resignation of Fishers, threatened the Conservatives to abandon their party political restraint and to demand an investigation. Therefore, in May 1915, a coalition was formed between the Liberals, led by Prime Minister Asquith, and the Conservatives around their party leader Andrew Bonar Law. In addition, this government was supported by parts of the Labor Party - although parts of the Labor Party no longer supported the government from 1914, because they did not want to betray their pacifist convictions. Asquith thus became the leader of a broad coalition government that also brought leading figures from the opposition to the cabinet. As a price for the Conservative support, several Liberal ministers had to vacate their posts because they were unacceptable to the Conservatives. This particularly affected the renegade and defector Churchill, who at the instigation of the Conservatives had to swap the Admiralty for the meaningless office of Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster . In addition, Asquith's longstanding and oldest political friend, Richard Haldane, fell victim to the formation of a coalition. Asquith gave in to pressure from the Conservatives, dismissing Haldane with virtually no resistance or a personal word, which Asquith's biographer Roy Jenkins cites as the most uncharacteristic flaw in Asquith's entire political career. In return, the majority of the leading conservatives were content with subordinate posts. Of the four most important offices they held only the Admiralty. For this purpose, the ammunition supply was cut off from Kitchener's department; Asquith ensured that Bonar Law was denied access to the newly created ministry and that Lloyd George became minister of munitions instead. The Dardanelles Committee, expanded in terms of personnel, replaced the council of war. The liberal Charles Hobhouse, who was also dismissed, then noted with resignation: “The breakup of the Liberal Party is complete, Ll.G. and his Tory friends will soon get rid of Asquith and the one or two real remaining Liberals. "

In late 1915, the continuing failures on the Western Front undermined confidence in Secretary of War Kitchener and the BEF Commander in Chief in France, Sir John French . Because of his indecisive leadership, French was blamed for the British failures and heavy losses. Kitchener had become intolerable to Bonar Law and Lloyd George; Asquith agreed with them in principle, but feared the public reaction to a dismissal of the popular Secretary of War. So he chose an indirect method and in November encouraged the hesitant Kitchener to go to the Gallipoli theater of war for two months and take a picture there. In the meantime he took over the post of Secretary of War provisionally himself and began in quick succession to do some important tasks that Kitchener had postponed. So he dismissed French in December 1915 and replaced him with his deputy and commander in chief of the 1st Army, Douglas Haig . For this purpose he appointed Sir William Robertson to Chief of the Imperial General Staff and should issue from now on in this function to the Cabinet strategic advice. With this achievement, Asquith showed his extraordinary administrative talents one last time in the eyes of his biographer Roy Jenkins. To this end, a change was made in the Dardanelles Committee, now called the Council of War again. In addition to Asquith himself, the reduced organ should now only include David Lloyd George, Reginald McKenna, Arthur Balfour and Andrew Bonar Law in order to enable a faster decision-making process; However, this intention was quickly dashed again by renewed personnel expansions and a fundamental lack of decision-making authority, which led to lengthy discussions in the cabinet about decisions already made in the war council.

In addition, the failure of the voluntary recruitment system had become evident and the coalition government was finally forced in early January 1916 to introduce compulsory military service for bachelors, which was extended to married men later that year. Again this measure met with opposition from within and from the Labor Party; John Simon stepped back. Asquith again adopted his characteristic wait-and-see attitude as the discussions progressed, causing great anger among politicians like Lloyd George, who were for a more radical approach to the handling of the war. Asquith's reputation was damaged by the prolonged indecision of this issue, and Asquith was unable to satisfy either supporters or opponents on this issue.

After the Easter Rising in Dublin, Asquith visited Ireland in May 1916 and came to the conclusion that the existing system of government had completely collapsed. He passed the task on to Lloyd George to negotiate a form of Home Rule with the two antipodes Carson and Redmond. The informal agreement provided for a provisional form of Home Rule for the south of Ireland with the exception of Ulster for the duration of the war. However, the agreement was sharply criticized by the unionists, especially Lansdowne and Walter Long were adamant. Bonar Law and the large majority of the Conservatives also refused, for constitutional reasons, for the Irish nationalists to remain in the House of Commons if it came into force; in the case of Home Rule, they found it unacceptable that the Irish nationalists should continue to tip the scales in the House of Commons. Redmond, on the other hand, was just as adamant as he only wanted to give up Ulster temporarily, but not permanently. Because of this stalemate, the old system had to be renewed in July 1916.

Fall

In the course of 1916 Asquith moved increasingly to the center of criticism; Asquith, who despised the press, declined to associate with it and promote his own cause. The powerful newspaper magnate Lord Northcliffe, owner of The Times and Daily Mail , on the other hand, worked towards his removal. As early as the munitions crisis of 1915, his two newspapers had harshly criticized the government and Minister of War Kitchener and exposed the deficiencies in supplies. Asquith became known in the British press on the one hand because of his wife Margot (who had spent part of her school days in Berlin and was still openly Germanophile during the war) and, on the other hand, because of his notoriously wait-and-see strategy, which he himself previously called “Wait and see ”, was harshly criticized. The pejorative nickname " Squiff" or " Squiffy" (English for " buzzed" or " slightly drunk"), because some observers at dinner parties saw it as too much alcohol, was now used regularly by his opponents.

Asquith's leadership of the war did not please certain liberal politicians and the Conservative Party. Lloyd George had criticized Asquith with other members of the government for the first time in mid-1915, because this initiative was lacking and no efforts were made to keep the individual public departments together, which would therefore each go their own way. Asquith's political opponents, including Edward Carson and Alfred Milner , accused Asquith of weak decision-making and indifference; Continuous lengthy discussions and numerous internal intrigues made a quick decision-making process in the cabinet almost impossible. The highly inflated war council lost its decisive power through the formation of a coalition. In practice, all the decisions made there were again lengthily discussed in the cabinet. Even after the formation of a coalition, there was a great deal of mistrust between conservatives and liberals, a result of the fierce political conflicts of the years before the beginning of the war. In addition, his opponents blamed Asquith for a number of political and military disasters, including the final failure of the Dardanelles expedition in late 1915, the Easter Rising in Ireland in April 1916 and the failed Battle of the Somme . In the course of the Somme battle, Asquith's gifted son, Raymond, also fell; his death and the previous loss of his longtime confidante Venetia Stanley (who married Junior Minister Edwin Montagu ) each meant a heavy blow to Asquith - losses from which, in the opinion of his biographers, he never recovered.

David Lloyd George gained a reputation for energetic and energetic action as ammunition minister and subsequently as minister of war. With the intention of excluding the Prime Minister from operational leadership, Lloyd George managed to secure the support of the Conservatives in mid-November 1916. A smaller war cabinet, consisting of four people headed by Lloyd George, was to be formed, while Asquith did not belong to it. Asquith initially accepted the proposal, but withdrew when a well-informed article appeared in the London Times about the incident, which presented him as excluded from the smaller war cabinet. He now demanded the chairmanship for himself. Thereupon Lloyd George submitted his resignation. However, since Bonar Law supported Lloyd George and threatened the resignation of all Conservative ministers from the cabinet, Asquith saw no other viable option and resigned himself on December 5, 1916. Asquith calculated at least the possibility that neither Lloyd George nor Bonar Law would be able to form a coalition and that he would then be given the chance to form a government. Immediately after Asquith's resignation, Bonar Law was invited by the king to form a government. He had already agreed with Lloyd George in advance that he would only try to form a new government if he could persuade Asquith to join it in a subordinate position. Otherwise, Lloyd George should try to form a new government. However, Bonar Law failed with his attempt to persuade him. A day later, King George Asquith, Lloyd George, Bonar Law, Balfour and Arthur Henderson came to a conference at Buckingham Palace to persuade them to form a national government. However, the meeting ended with no results. After Asquith again declined the option to remain in another cabinet post, Lloyd George became head of the new coalition government a day later. Asquith, ousted as Prime Minister, went into the opposition with his supporters, while a (smaller) part of the Liberals under the new Prime Minister Lloyd George stuck to the coalition.

Immediately after his fall, Asquith attended a general meeting of Liberal MPs from both Houses at the Reform Club in London . In statesmanlike words, he defended his actions and explained the reasons for his failure. He then appealed to the patriotism of those present and called on them to support the new government. Asquith's fall was felt as a turning point immediately after the events. He was called “the last Roman” by his followers and devoted observers, a symbol of abandoned old virtues.

In the opposition

Asquith's Liberal Group now assumed the role of an opposition, which increasingly led to a split in the Liberal Party. Attempts from various sides, including Lloyd George, to repair the break in the initial phase failed. Asquith turned down an offer to serve as Lord Chancellor because he mistrusted Lloyd George. Above all, his unyielding wife Margot kept Asquith's injured pride alive.

The so-called “Maurice Debate” in the spring of 1918, based on the public accusation of General Frederick Maurice , led to a strong hardening of the fronts; General Maurice had accused Lloyd George in the Times of deceiving the public about the current situation on the Western Front , whereupon Asquith's Liberals forced a debate in the House of Commons and then to divide the House. Although the debate remained inconclusive, it deepened the rift between coalition supporters and Asquith's liberals. Asquith's faction was clearly defeated in the division by 293 votes to 106 for the government (and many abstentions on the part of the Liberals). Lloyd George felt betrayed by the heated debate at a moment of escalating military crisis and held a personal grudge against those who had voted against him. All those who voted against him did not receive a letter of support from the government in the upcoming “coupon election”. In September 1918 and again on the occasion of the armistice, Asquith rejected offers from Lloyd George to return to the coalition as Lord Chancellor and to nominate two of his own supporters for the cabinet. Conversely, Lloyd George Asquith's request to be part of the British delegation in the Paris peace negotiations .

For the 1918 general election, the coalition around Lloyd George and the Conservatives had sent letters of support to certain Liberal and Conservative candidates before the election campaign, identifying them as supporters of the existing coalition. No letter was sent to anyone who voted against him in the previous Maurice debate. Asquith disparagingly referred to these letters as coupons, and the name “coupon choice” has been a common term for choice ever since. The coalition won the election comfortably, with the Conservatives being the clear winner. The liberals around Asquith, who remained committed to their old issues such as free trade during the election campaign, experienced a debacle; they were only able to move into the House of Commons with 26 of their 253 candidates and have shrunk to a rump party. They lost their role as the leading opposition party to the Labor Party . In the election, Labor had emancipated itself from the Liberals for the first time in its own election campaign and no longer made any agreements with the Liberals in the individual constituencies. Asquith himself also lost his parliamentary seat in East Fife, although the coalition had not put up an opponent.

However, he continued to lead the Liberal Party. He returned to the House of Commons through a by-election in 1920. However, in a hostile House of Commons - Asquith called it the worst House of Commons he has ever sat in - he couldn't set any accents. A reunification promoted by many simple liberal members of parliament failed due to resistance from Asquith himself and the old leaders around him. Herbert Gladstone (son of the former Prime Minister) said in 1923 that it was clear that Asquith was no longer an effective leader, but that Lloyd George would have to be denied his successor. Michael Kinnear sees Asquith's persistent resentment and his thirst for revenge against Lloyd George as the decisive factor that made a quick reunification of the two Liberal parties impossible.

In 1924 Asquith played an important role in the formation of the Labor minority government, of which Ramsay MacDonald became Prime Minister . After the Conservative Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin surprisingly called a lower house election at the end of 1923, both liberal factions agreed on a short-lived electoral alliance that would operate under the banner of free trade. Baldwin's Conservatives, who had campaigned for tariffs on his initiative, were defeated in the December 6, 1923 election and lost 86 of their 344 seats, while both Labor and Liberals gained lower house seats. The result was a Hung parliament in which none of the three big parties could win an absolute majority. Asquith now publicly announced on December 18 that the Liberals would not form a coalition with the Conservatives just to keep Labor out of the government. While some conservative voices and saw looming a Bolshevism Churchill, expressed Asquith, a Labor government "could hardly be tried under more secure conditions." The literary historian Edmund Gosse over he said condescendingly, he would Ramsay Macdonald not steal an hour of his brief reign; "Let him enjoy it while he can, because once out of office no one will ever hear from him again." Asquith's decision was based on the hope that Labor would turn out to be incompetent and the Liberals would turn out to be incompetent after a year or two would displace. That is why he decided to tolerate Labor and shied away from a coalition agreement so that the liberals would be free from the stigma of what he saw as the failure of the government. Lloyd George supported him in his course.

Labor party leader MacDonald accepted this challenge. For years his two main goals had been to prove to the electorate on the one hand that Labor could not be a radical but a constitutional party that could manage a mixed economy and, on the other, to oust the liberals from the political center. Therefore he formed a minority government that was dependent on the tolerance of the liberals. Labor quickly managed to get some successes on their government record; so France could be persuaded to agree to the Dawes Plan (which should regulate the reparations Germany to the victorious powers ). The Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Snowden also showed himself to be a cautious actor who was committed to fiscal integrity in the sense of Gladstone. The break came after a few months, when Labor wanted to sign a trade agreement with the Soviet Union and because of the so-called Campbell Affair : The communist newspaper editor JR Campbell had asked the military to mutinate in an article. Legal prosecution of Campbell was blocked by the government under pressure from some Labor backbenchers. Thereupon conservatives and liberals turned together against the Labor government and forced a debate in the lower house, in which they suggested a parliamentary commission of inquiry. The Labor government opposed this and lost a vote of confidence, whereupon it now called new elections. Asquith made his final speech in the House of Commons during the debate.

The 1924 election , which came after the fall of the Labor government, became Asquith's last campaign. The Liberals were at a disadvantage from the start. Asquith's faction was short of money. Lloyd George had a large personal campaign fund, which he had acquired through the sale of Peerages during his reign until 1922 . However, he refused to share this with Asquith's Liberals until he himself was elected leader of a reunited Liberal Party. That is why the Liberals could only nominate 340 candidates nationwide. The election turned into a debacle - the Liberals could only win 40 seats in the lower house; in addition, their share of the vote decreased from 4.2 million to 2.9 million. Labor, on the other hand, lost 40 seats, but gained a million votes nationwide and continued to establish itself as the second party in the power structure. "Matt to the point of indifference", Asquith, now 72 years old, in the eyes of some observers, led his last election campaign in Paisley, Scotland. In the end, he lost his constituency by 2,000 votes to the Labor candidate, a former Liberal. The king now offered him a peerage. Asquith initially intended to reject the king's offer, as he believed that he would rather die as a commoner than Pitt the Younger and Gladstone before him . However, he finally accepted the offer and was knighted as Earl of Oxford and Asquith in 1925 . He had chosen the title of Earl of Oxford himself because he had a great background in the person of Robert Harley, 1st Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer . He found the debates in the House of Lords to be of substantially worse quality and did not enjoy the political activities there. In 1925 he was a possible candidate for the chancellorship of the University of Oxford. However, the conservatives rallied around an alternative candidate in order to prevent their old opponent from being chosen. Asquith and Lloyd George had another argument about the general strike of 1926 , which they resolved in published letters; Asquith criticized the general strike, while Lloyd George was ambivalent. Lloyd George won this final argument with this attitude. After Asquith's ennoblement, Lloyd George succeeded him as leader of the Liberal MPs in the House of Commons, but Asquith remained party leader. On October 15, 1926, he finally resigned as party leader. Lloyd George succeeded him and was able to overcome the split in the Liberal Party.

Last years of life

Asquith spent his final years in retirement; In addition to private hobbies, he wrote his memoirs. The last years of his life were overshadowed by financial problems. In January 1927 he suffered a severe stroke that forced him to use a wheelchair for several months; another severe stroke in late 1927 paralyzed him almost completely. His daughter Violet wrote of his condition: "To see Father's glorious mind shatter and - like a great ship - sink is a pain beyond imagination for me." On the morning of February 15, 1928, Asquith passed away; at his own request he received a simple burial in the All Saints' church in Sutton Courtenay. Asquith's second wife Margot survived him by 17 years; she died in 1945.

Asquith as the author

1923 Asquith published his book The Genesis of the War (dt .: The origins of the war ), in which he dealt with the causes of the First World War. The book, dedicated to Sir Edward Gray, was a reply to the memoirs of Wilhelm II , in which Asquith rejected the one-sided accusations of the exiled German emperor and the thesis of the encirclement policy, while in his remarks the aggressive German one initiated by Wilhelm II Identified world politics as one of the causes of war. In 1926 he finally published his two-volume memoir, Fifty Years of Parliament (Eng .: Fifty Years of Parliament). Shortly after his death, Memories and Reflections appeared, also in two volumes .

Research history

After Asquith's death, his widow Margot and daughter Violet tried to preserve Asquith's memory. JA Spender and Cyril Asquith published a two-volume biography in 1932 that depicts Asquith in an extremely favorable light. Margot also described Asquith as an outstanding statesman in her own memoir. After Margot's death, Violet preserved Asquith's legacy all the more resolutely and occasionally also brought libel suits against authors who brought out critical publications; so she also successfully brought a libel suit against Robert Blake, who had quoted a controversial World War II memory of Lord Beaverbrook in his biography of Andrew Bonar Law in 1955 . In the early 1960s she then granted Roy Jenkins access to some of the estate material for a biography. Jenkins described Asquith's political work ( Asquith: Portrait of a Man and an Era. ) Also tended to be very benevolent, but on an objective basis.

After that, Asquith's reputation faded again and as a result, a wave of authors in a series of benevolent works on David Lloyd George grappled with Asquith increasingly critically. Beaverbrook and especially AJP Taylor influenced the perception to the detriment of Asquith, while Lloyd George's reputation experienced a renaissance in the opposite direction.

In 1976 a critically balanced biography of Stephen Koss was published. Asquith's correspondence with his confidante Venetia Stanley is an important source for historians; Asquith wrote to her up to four times a day between 1910 and 1915, sometimes during cabinet meetings, and openly shared his personal observations and political problems with her. He also reported internals from the cabinet. These letters are particularly relevant for the decision-making processes and procedures in the Cabinet in the first phase of the war, in which no written protocols have yet been drawn up. In 1982, an edited version of Asquith's letters appeared in Asquith: Letters to Venetia Stanley, edited by Michael and Eleanor Block.

In 1994 George H. Cassar published the book Asquith as War Leader , in which he dealt with Asquith as a leader in World War I. In it he came to a revisionist conclusion and saw Asquith's record as a leader in the world war much more positively than had been the canon of current research up to now. Colin Clifford published a family portrait of the Asquiths in 2002. As part of the series 20 British Prime Ministers of the 20th Century , the short biography Asquith by Stephen Bates was published in 2006 . In 2019, HH Asquith: Last of the Romans by V. Markham Lester was published.

A quantitatively unmanageable number of publications and books have appeared over the years on the outbreak of the First World War and the decision of the British Cabinet to enter the war. In addition, there are many publications on the decline of the Liberal Party , beginning with George Dangerfield's influential book The Strange Death of Liberal England in 1935 , in which Asquith is usually assigned a strong personal responsibility. Roy Jenkins also published Mr. Balfour's Poodle in 1954 , an account of the conflict between the Liberal government and the House of Lords.

Assessment of Asquith as Prime Minister

According to Roy Hattersley , modern Britain was born during Asquith's aegis. Although Asquith is now a largely forgotten prime minister, his government was one of the most important and far-reaching, said Stephen Bates in 2006. The 1909 people's budget was mainly due to him, as was the introduction of old-age pensions, a lasting social achievement.

H CG Mathew sees Asquith's decision to lead Britain to war as the most important and momentous decision of any British Prime Minister in the 20th century. Military historian Basil Liddell Hart wrote in 1970 in his history of the First World War that his fall was due to the demand for a more efficient and rigorous conduct of the war . Robert Blake made an often repeated distinction between Asquith the Prime Minister in the years before the outbreak of war and Asquith the leader in wartime: Asquith, as the longest ruling Prime Minister in a century, had many outstanding personal qualities. However, he was tired in 1916 and although a great prime minister in peacetime, like other successful prime ministers before him, his disposition was unsuitable to lead the nation through a great war.

Asquith's historical stature was rather increased in the wake of the decline of the Liberal Party, argued his biographer Stephen Koss in 1976. Asquith's fall had brought about the decline of the Liberal Party. Asquith was also partly to blame for this, judged Dick Leonard in 2005. Likewise, John Campbell saw Asquith's personal vanity and his rivalry with Lloyd George as the cause of the deep fall of the Liberal Party. He also saw Asquith's refusal to join the cabinet as minister under either Bonar Law or Lloyd George in 1916, an extraordinarily arrogant attitude in a moment of national crisis. Other former prime ministers of the past - such as Wellington under Peel , Russell under Palmerston, or Balfour under himself - had not been too proud as precedents to serve in another office under another man. Even Neville Chamberlain was loyal in the next great war in Churchill's war government occurred; Asquith, on the other hand, out of wounded pride and a reluctance to serve with men who had behaved shabbily towards him, could not bring himself to rejoin the cabinet.

V. Markham Lester said in a résumé in his biography published in 2019 that, until the outbreak of war in 1914, Asquith was to be seen as one of the greatest parliamentarians and prime minister of all, as his career up to this point had been an uninterrupted run of success. The war then led to a personal loss of reputation, and Asquith's stubborn adherence to the leadership of the Liberal Party, combined with his argument with Lloyd George, led to the accelerated decline of the Liberal Party.

Asquith came fourth (behind Churchill, Lloyd George and Clement Attlee ) in a BBC poll of historians, politicians and political commentators aimed at voting for the best prime minister of the 20th century .

Honors