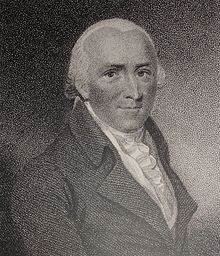

Humphry Repton

Humphry Repton (often mistakenly Humphrey) (born April 21, 1752 in Bury St. Edmunds , † March 24, 1818 in Aylsham ) was a well-known English landscape architect of the 18th century . He succeeded the famous landscape architect Capability Brown , who died in 1783 . Around 1800, Repton designed Russel Square and Bloomsbury Square in London. In addition, he distinguished himself as a botanist who did not shy away from the difficulties of the increasingly mechanized sowing of the 19th century .

Life

Repton was the second surviving child of tax collector John Repton (baptized 1714, † 1775) and his wife Martha Fitch († 1773) from Moor Hall in Suffolk. The family moved to Norwich in 1762 , where his father ran a haulage company. Humphry Repton attended school in Bury St. Edmunds and Norwich. His father trained him to be a businessman, so he attended the school of Algidius Zimmerman in Workum in the Netherlands for a year to learn Dutch. He then lived in Rotterdam with the family of the wealthy banker Zachary Hope. Here he came into contact with the "better society" and acquired a preference for a life of luxury. At 16 he returned to Norwich and became an apprentice to a cloth merchant. During his training, he traveled to Germany and the Netherlands, where he admired the gardens there.

On May 5, 1773 he married Mary Clarke (1749-1827) and started his own business with his father's money. However, bad speculations, shipwrecks and a lack of industry led to constant losses. Stephen Daniels, his biographer, describes his taste for spending rather than making money. After the death of his parents - they were buried in Aylsham - he bought Old Hall in Sustead near Cromer , on the Felbrigg estate of William Windham , a Whig politician, sold his company and lived on his paternal inheritance. His brother John ran a successful estate in nearby Oxnead , and his sister Dorothy lived with her husband in Aylsham.

In Old Hall he botanized, read books from lending libraries, kept correspondence, wrote poetry, played the flute and drew. Since he could not handle money and did not have the income of a country nobleman whose lifestyle he imitated, however, he ran into increasing financial difficulties. When Windham was named Chief Secretary for Ireland in 1783 , he accepted a position as its private secretary. Repton traveled with him to Dublin , where he shone socially and made sketches of picturesque landscapes. However, Windham resigned after a month because he feared damage to his health and fired Repton without even reimbursing him for travel expenses. Repton then traveled to Bath , where he tried to earn a living as a cartoonist. With the impresario John Palmer , he drafted a plan to reform the stagecoach system , which probably drew on his father's experience. The plan was accepted, but Repton and his partner earned nothing from it. On returning to Norfolk, he had to sell his country estate and move his family to a dog house on Hare Street , Essex . Here he wrote essays and plays.

Entry into landscape architecture

Repton was 35 years old and had four children when he decided to offer himself as a landscaper for the upper class. No one had taken his place after Capability Brown's death . Repton received its first order in 1788 for the large country estate of Catton Park north of Norwich . Despite the lack of experience in practical horticulture, the garden became a surprising success. The reason for this was certainly his talent, but also the clarity with which he presented his designs. For this purpose, he produced so-called “Red Books” with watercolors and explanatory text as well as overlays for before and after views. Repton was good at flattering the owners and suiting their tastes. In 1791 Repton laid out the garden of Holwood House in Kent, William Pitt's country home . A daughter of Pitts, Harriet, was married to a son of Lord Eliot from Cornwall, so that Repton was commissioned to redesign Port Eliot , presumably through Pitt's recommendation in 1792 . Lord Eliot recommended Repton so that he also redesigned the gardens of Antony House , Catchfrench , Tregothnan and Trewarthenick in Cornwall .

Design development

In England the gardens were regularly laid out until the end of the 17th century. Capability Brown had become more important in developing a natural style introduced in the early 18th century. Repton's efforts now concentrated on integrating the respective structures better into the design of the environment. He reintroduced the formal terraces , balustrades , pergolas and flower gardens that were customary in the past to create a bright, colorful overall complex, with lawns up to the house and delightful views of the surrounding parkland. This design would become common practice during the 19th century.

A telling example of his endeavors is the romantic landscape park of Blaise Castle near Bristol , which Jane Austen described in one of her novels as the most beautiful place in England. Repton anticipated a further development of the 19th century with the Woburn Abbey . Thematically divided garden areas with a Chinese garden, American garden, arboretum and “forcing garden”, in which suitable plants were encouraged to bloom out of season. In Ashbridge he created 15 different specialized gardens.

Architecture played an important role in many of Repton's landscape designs, he referred to himself (as the first) as a landscape architect. In the 1790s he therefore often worked with the then unknown architect John Nash , and later with his own sons.

According to a publication from 1794, his design criteria included congruity, utility, order, symmetry, painterly effects, complexity (intricacy), diversity, simplicity, connection, greatness, appropriateness and liveliness.

Executed gardens and parks

Important English mansions with gardens and parks designed by Repton are:

- Antony House in Cornwall

- Ashton Court near Bristol in Somerset

- Attingham Park between Shrewsbury and the Severn , owned by the Berwick family

- Bayham Abbey

- Beaudesert in Staffordshire (1814)

- Bolwick Hall

- Catton Park and Old Catton in Norwich

- Clumber Park

- Cobham Hall

- Dyrham Park

- Endsleigh House (with a red book now in Woburn, watercourse and cottage orné ),

- Grovelands Park

- Harewood House

- Hatchlands Park

- Highams Park in Woodford

- Kenwood House

- Longleat House

- Plas Newydd , Anglesey on Menai Street , owned by the Marquis of Anglesey

- Rode Hall in Cheshire

- the Royal Pavilion in Brighton

- Royal Fort in Bristol

- Shardeloes

- Sheringham Park

- Sheffield Park

- Stanage Park

- Stanmer Park

- Tatton Park

- Uppark Loughton

- West Wycombe Park

- Woburn Abbey .

Works

Repton put his theoretical considerations, practical experiences and observations down in various books.

- "Sketches and hints on landscape gardening: Collected from designs and observations now in the possession of the different noblemen and gentlemen, for whose use they were originally made. The Whole Tending to Establish Fixed Principles in the Art of Laying out Ground ”, 1794. Digitized by RERO

- "Observations on the theory and practice of landscape gardening: including some remarks on Grecian and Gothic architecture: collected from various manuscripts, in the possession of the different noblemen and gentlemen, for whose use they were originally written", 1803. Digitalisat der ETH Zurich

- "An Inquiry into the Changes of Taste in Landscape Gardening", 1806.

- "Designs for the pavilion at Brighton", 1808.

- "Fragments on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening", 1816.

literature

- André Rogger: The Red Books of the landscape artist Humphry Repton . Wernersche Verlagsgesellschaft , Worms 2007. ISBN 978-3-88462-225-4

- Rafael de Weryha-Wysoczański: Strategies of the Private. To the landscape park of Humphry Repton and Prince Pückler . Berlin 2004. ISBN 3-86504-056-X

Web links

- Stephen Daniels: “Repton, Humphry (1752-1818)” . In: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, edited by HCG Matthew and Brian Harrison. Oxford: OUP, 2004. Online ed., Edited by Lawrence Goldman, January 2012, accessed February 11, 2013.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Stephen Daniels, “Repton, Humphry (1752-1818)” . In: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, edited by HCG Matthew and Brian Harrison. Oxford: OUP, 2004. Online ed., Edited by Lawrence Goldman, January 2012, accessed February 11, 2013.

- ^ Mary Keen: The Glory of the English Garden . London, Bulfinch 1989, p. 118.

- ^ Mary Keen: The Glory of the English Garden . London, Bulfinch 1989, p. 120.

- ^ The National Heritage List: Port Eliot. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on May 2, 2014 ; Retrieved June 17, 2013 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Mary Keen: The Glory of the English Garden . London, Bulfinch 1989, p. 122.

- ^ Mary Keen: The Glory of the English Garden . London, Bulfinch 1989.

- ^ Mary Keen: The Glory of the English Garden . London, Bulfinch 1989, p. 120.

- ^ Roy Strong: Creating Small Formal Gardens . London, Conran Octopus 1989, p. 29.

- ↑ Guy Cooper, Gordon Taylor: The Curious Gardener . Headline, London 2001, p. 26.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Repton, Humphry |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Repton, Humphrey (wrongly) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | English landscape architect |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 21, 1752 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Bury St. Edmunds |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 24, 1818 |

| Place of death | Aylsham |