Scheidemann cabinet

| Scheidemann cabinet | |

|---|---|

| First government of the Weimar Republic | |

|

|

| Prime Minister | Philipp Scheidemann |

| choice | 1919 |

| Legislative period | National Assembly |

| Appointed by | President Friedrich Ebert |

| education | February 13, 1919 |

| The End | June 20, 1919 |

| Duration | 0 years and 127 days |

| predecessor | Council of People's Representatives |

| successor | Cabinet peasant |

| composition | |

| Party (s) | SPD, center and DDP |

| representation | |

| National Assembly | 330/423 |

The Scheidemann cabinet was the first cabinet of the Reich government during the Weimar Republic . It met for the first time on February 13, 1919. It was responsible until June 20, 1919, followed by the Bauer cabinet . The Scheidemann cabinet was confronted with internal unrest and the question of the acceptance of the Allied terms of the Peace Treaty of Versailles . Since Philipp Scheidemann refused to sign, he resigned. This meant the end of the cabinet.

Government formation

From the election to the German National Assembly on January 19, 1919, the SPD emerged as the strongest party with 37.9%. The USPD received 7.6% of the vote. The strongest bourgeois party was the DDP with 18.5%, the center and Bavarian People's Party together made up 19.7%. The DNVP came to 10.3% and the DVP to only 4.4%.

Forming a government against the SPD was hardly conceivable. But contrary to what some hoped and what others feared, a socialist majority government was not possible. A socialist minority government , however, was very unrealistic. This would have been under constant pressure from the bourgeois opposition, and the differences between the SPD and the USPD were too great. A minority government of the SPD and DDP would also have been conceivable. But since the Democrats feared they would be dominated by the stronger partner, they rejected this option and brought the center into play as the third coalition partner. This Weimar coalition meant the new edition of the cooperation in the last Reich Cabinet of the Prince of Baden from October 1918. The SPD made it a condition that the coalition partners "the unreserved recognition of the republican form of government, a financial policy with sharp use of wealth and property and far-reaching social policy and Socialization of the companies suitable for this ”would. The SPD quickly came to an agreement with the DDP. In the center there were definitely voices that rejected a coalition with the SPD. Matthias Erzberger in particular succeeded in organizing a majority for participation in the center parliamentary group.

After the election to the National Assembly, the Council of People's Representatives continued to govern until February 11, when Friedrich Ebert was appointed provisional President , who entrusted Philipp Scheidemann with forming a government.

Competencies

In terms of constitutional law, the government was different from its predecessors and successors. It was formed according to the law on provisional imperial power . Many provisions in it were unclear. A big difference to the previous and successor cabinets was that it was purely a collegiate body. The Prime Minister did not have any special powers. In fact, it wasn't even mentioned in the law. The position was only mentioned in the decree of the Reich President on the establishment and designation of the highest Reich authorities of March 21, 1919. The Reich Minister President was therefore actually only a moderator and discussion leader. Incidentally, there was basically only the Reich Chancellor as Reich Minister. Now its competencies were divided among the various ministers. The heads of department were responsible for their ministries. Due to the construction, disputes between the ministries and the ministers were inevitable. It was also unclear who ran the “business of the empire”. In the law on provisional empire power, this was the Reich President. However, in the decree of March 21, this was the Reich Ministry.

The Reich Chancellery was a mere auxiliary body to the Prime Minister and the Cabinet as a whole, but was not an instrument for increasing Scheidemann's influence over the other ministers. Curt Baake , formerly a social democratic journalist, was initially head of the Reich Chancellery. He was followed on March 3rd by the career clerk Heinrich Albert .

Composition of the Cabinet

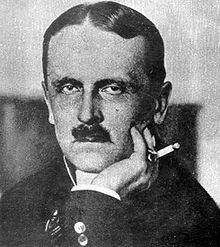

Instead of the traditional title Reich Chancellor, Scheidemann's official title was President of the Reich Ministry or Reich Minister President. Scheidemann's appointment was completely undisputed. Scheidemann was a good speaker, but was rather conflict-averse. He saw himself in the cabinet as a kind of moderator, mediated in disputes and proved to be pragmatic and undogmatic. In parliament he represented the basic lines of the government and mostly put the common in the foreground.

With regard to the social democratic ministers, there was clear continuity with the last council of the people's representatives. Otto Landsberg became Minister of Justice. Gustav Noske , probably the most controversial social-democratic politician, was already responsible for military matters in the Council of People's Representatives and now took over the Reichswehr Ministry. Rudolf Wissell from the trade union wing of the SPD became Reich Economics Minister. The problem was that, as such, he was pursuing a dogmatic course with the aim of structural changes in the direction of the common economy and thus met with considerable resistance in the cabinet. Even Gustav Adolf Bauer came from the trade unions and had distinguished himself as an expert in occupational safety and health. Already in Max von Baden's cabinet he headed the new Reich Labor Ministry , which he also headed during the revolution and in the Scheidemann government. The same was true for Robert Schmidt, who had been Undersecretary of State in the Reich Food Office in 1918 and now took over the Reich Food Ministry. Before the war, Eduard David was considered to be one of the leading figures of the revisionist wing of the SPD. In 1918 he had been Undersecretary of State in the Foreign Office and, together with Karl Kautsky, had begun to investigate the question of war guilt . As a minister without a portfolio, the question of peace and war guilt remained his main task.

With Matthias Erzberger, Johannes Bell and Johannes Giesberts, the center had three ministers in the Scheidemann cabinet. Matthias Erzberger came from the Christian trade unions and had played an important role in the final phase of the war as State Secretary and head of the German Armistice Commission. As a minister without portfolio, he was still entrusted with the peace negotiations and was also one of the central figures in the cabinet. Bell took over the Reich Colonial Ministry and Giesberts the Reich Post Ministry. But neither played a significant role in government.

From the DDP, Hugo Preuss , Georg Gothein and Eugen Schiffer belonged to the cabinet. Preuss was a professor of constitutional law and since November 1918 State Secretary in the Reich Office of the Interior. He was in charge of drafting the new Reich constitution and was Minister of the Interior in Scheidemann's cabinet. There he hardly played a role beyond constitutional issues that were rarely discussed and was usually represented at the meetings. Gothein had been a Chamber of Commerce syndic and in Scheidemann's cabinet was first a minister without portfolio, then a Reich treasure minister. He played a role in the cabinet as a liberal, market economy counterweight to Wissell. Schiffer had previously belonged to the National Liberals and had already made a career in government as State Secretary of the Reich Treasury during the Empire . He was appointed to the cabinet primarily as a financial specialist less than a party representative. He resigned in April 1919. He was succeeded by Bernhard Dernburg , who had been State Secretary in the Imperial Colonial Office during the Empire .

Although Ulrich Graf Brockdorff-Rantzau did not belong to the DDP, the professional diplomat was assigned to this party. He was appointed foreign minister. Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Koeth , Reich Minister for Economic Demobilization , was not assigned to any party . With the end of the demobilization and the dissolution of his ministry, he resigned on April 30, 1919. The Prussian War Minister Colonel Walther Reinhardt was a member of the cabinet, but had no voting rights there. The head of the naval office, Vice Admiral Maximilian Rogge , officially had neither a seat nor voting rights, but still took part in the meetings. After the Reichsmarineamte was dissolved and the Admiralty was founded, Rear Admiral Adolf von Trotha took his place in March 1919 and also became an official member of the cabinet.

Constitutional order

During the time of the Scheidemann cabinet, the fundamental decision about the future political order was made. Constitutional issues played only a minor role in the cabinet meetings. The struggle over the shape of the constitution centered on the National Assembly and, in particular, on the Constitutional Committee. Only individual questions such as the transfer of responsibility for the railways to the Reich or the inclusion of the workers' councils in the constitution were discussed more in the cabinet. It succeeded against the resistance of Bavaria and the Prussian Minister Wilhelm Hoff, the transfer of the railways to the Reich. The inclusion of the workers 'councils in the constitution was not provided for in Hugo Preuss' draft constitution approved by the cabinet. But the government was at times forced to make concessions under pressure from the workers. In the course of the debate, the question was then increasingly defused. Hardly anything was left of the councils' claim to power in § 165.

Revolutionary unrest

The main task of the government was to take care of the internal situation. A large part of the population suffered from inflation and supply difficulties. A second revolutionary phase fell during the time of the Scheidemann cabinet.

There were separatist movements in both the west and east of the empire. The problem with combating these tendencies in the Rhineland was that the government only had limited influence in the occupied territories. There were also efforts to break away from the empire in the province of Posen . Militarily, Poznan was entirely in Polish hands. There were border conflicts, and the government threatened the danger that the German population there could act unauthorized.

In large waves of strikes, workers in the Ruhr area in particular tried to achieve further goals in addition to the achievements of the November Revolution ( socialization movement in the Ruhr area ). Wage movements and demands for a reduction in working hours were combined with fundamental questions about the establishment of a council system or the socialization of industry. The major strike in January was followed by others in February and April. The goals and carriers were different. Syndicalists and communists played a not insignificant role in this . Since the movements were sometimes associated with violence, a confrontation with the Scheidemann government had to take place. In order to combat the supposed “Bolshevik danger”, the latter relied not least on politically far right-wing Freikorps . The strike movement was crushed through negotiations and violence.

Mainly supported by the left wing of the USPD, there was also a movement in Central Germany that called for greater participation by workers in the factories. After negotiations failed, a general strike broke out at the end of February, in which three quarters of the workers in central Germany took part. The government responded with a dual strategy. On the one hand, they had Halle an der Saale occupied by the military and, on the other hand, they promised to meet the demands by introducing works councils. On the basis of the recommendations of the Socialization Commission , she promised to socialize coal and potash mining. On this basis, the general strike in central Germany was ended in early March.

A general strike also began in Berlin on March 4th. However, this was much more political than in the other two areas mentioned. Here it was about the implementation of resolutions of the Reichsrätekongress . After the majority Social Democrats, USPD and trade unions withdrew from the strike, the strike was only supported by the KPD. Gustav Noske in particular was responsible for putting down the March fighting in Berlin with violence. Around 1,000 people fell victim to the fighting, including numerous bystanders and unarmed.

During this time council republics arose in various parts of the empire that did not recognize the central government. Among them was the Bremen Soviet Republic . The best-known example was the Munich Soviet Republic , which came into being after the assassination of Prime Minister Kurt Eisner on February 21 and went through various phases. The first phase lasted from April 7th to 13th. The Soviet Republic was mainly supported by intellectuals. This was followed by a communist-dominated phase. A Red Army was formed to counter the threat of defeat by the central government. In fact, Noske ordered government troops and volunteer corps to use force against the Soviet republic. Weakened also by internal disputes among its supporters, the movement was suppressed by the troops. Hundreds of people, including numerous civilians, lost their lives. In Munich, the council movement gave a boost to the political right and anti-Semitism. The second phase of the revolution ended with the suppression of the Munich Soviet Republic.

Socialization of the economy?

Despite the promises of the government, the concrete implementation of socialization remained very limited. Wichard von Moellendorff , State Secretary in the Reich Ministry of Economics, presented a concept of the common economy, which was based not so much on socialist, but on conservative ideas. He envisioned an “ economy that is planned and controlled in favor of the national community ”. Private ownership of the means of production should be preserved but publicly controlled. In addition, Moellendorf also aimed at the initially temporary elimination of the right to strike. Minister Rudolf Wissell made this concept his own.

For various reasons, violent opposition also arose within the cabinet. Robert Schmidt argued that the ideas had little to do with the SPD's Erfurt program, which explicitly provided for the abolition of private means of production. For the liberal Georg Gothwein, the concept boiled down to “regulated planned economy” and “perpetuating the forced economy in a capitalist guild form”.

The socialization was concretized by two laws on the coal and potash industry. The ownership structure was not called into question, but compulsory syndicates were introduced. In Reichskohlen- and in Reichskalirat but were even workers' representatives, employers there were in the majority. Another law on socialization was passed by the National Assembly on March 13th. After that, the Reich was empowered to transfer companies into the public economy by law.

It was characteristic of the government's handling of the socialization issue that it did not forward the report of the Socialization Commission with the recommendation of the socialization of coal mining to the National Assembly until a de facto decision had already been made on the socialization issue with the adoption of the aforementioned laws.

War guilt issue and peace treaty

In March 1919 the cabinet dealt with the question of war guilt in the presence of Friedrich Ebert . With a view to the peace conference in Versailles , in the opinion of the Reich President, it was necessary to come to a clear position. The misconduct of the imperial regime should be clearly stated and Ebert even pleaded for a corresponding process. The majority of the cabinet, with the exception of the former national liberal Eugen Schiffer, supported this. In April, the government revisited the war guilt issue after the Karl Kautsky investigation was open . The files left no doubt as to Germany's complicity in the outbreak of war. While Johannes Bell spoke out against publication, Eduard David pleaded for it. Scheidemann apparently did not take part in the discussion. The cabinet did not come to an agreement on this matter, but the Reich Minister-President recommended that it should not be published for the time being. In June 1919, the Foreign Office published a “white book” that was rather euphemistic. It was not until the end of 1919 that the “German documents on the outbreak of war” appeared without being able to influence the public judgment in any significant way.

For the Allies, the war guilt of the Germans was already established, it must remain unclear what effect a timely publication of the documents would have had. In Versailles, the peace conditions of the Allies were handed over to the German peace delegation on May 7, 1919. The Reich government had failed to prepare the public about possible harsh conditions in advance. The majority still hoped for a comparatively favorable mutual agreement and was accordingly outraged by the harsh conditions. These included, among other things, considerable territorial losses in favor of the new Polish state in the east and the loss of Alsace-Lorraine to France in the west . The colonies were also lost for good. The German military potential should be massively curtailed. From now on, the Reichswehr should not include more than 100,000 soldiers. There were also reparations payments that were not yet fully quantified. In Article 231 of the treaty, Germany and its allies were identified as guilty of the outbreak of war.

The government now faced the difficult question of whether or not to accept these terms. Initially, those who refused to sign the peace treaty dominated. The rejection front seemed to encompass the entire political spectrum from the German nationalists to the SPD, but also unions and employers. The Reich Foreign Minister and Scheidemann expressed their views accordingly. He said in a meeting: "What hand should not wither that puts itself and us in this fetter."

In the cabinet, it was above all the DDP ministers who strictly rejected the peace conditions. Otto Landsberg and Gustav Bauer from the SPD and Johannes Giesbert from the center followed suit. The hope of being able to bring about some alleviation through a tough attitude played a role in this. Matthias Erzberger, head of the German peace delegation, but Eduard David and Gustav Noske also spoke out against this. In the event of a rejection, they warned of a complete occupation of Germany.

Within the National Assembly, the factions of the SPD and the center were divided. A narrow majority in the SPD parliamentary group declared itself against accepting the conditions on May 12th. The situation began to move when the Allies responded to the German counter-proposals on June 16. The conditions were only slightly softened and the attitude towards the question of war guilt was not only confirmed, but tightened. In addition, the German side was given five days in which to make a decision.

Foreign Minister Ulrich Graf Brockdorff-Rantzau and the DDP stuck to their negative stance. The center wanted to agree under protest. In front of the SPD parliamentary group, Scheidemann and Landsberg threatened to resign, although there was also an agreement there. Behind it was Noske's report that military resistance was out of the question. The supply situation was also still catastrophic. There was heated argument in the cabinet over the question of acceptance. Supporters and opponents of an assumption were equally strong. When the conflicts in the cabinet hardened on the evening of June 19, Scheidemann, Brockdorff-Rantzau and Landsberg resigned. This was the end of the Scheidemann cabinet.

List of Cabinet Members

| Scheidemann cabinet February 13, 1919 to June 20, 1919 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prime Minister | Philipp Scheidemann | SPD | ||

| Deputy Prime Minister |

Eugen Schiffer (until April 19, 1919) |

DDP | ||

|

Bernhard Dernburg (from April 30, 1919) |

DDP | |||

| Ministry of Foreign Affairs | Ulrich Graf von Brockdorff-Rantzau | independent | ||

| Interior | Hugo Preuss | DDP | ||

| Judiciary | Otto Landsberg | SPD | ||

| Finances |

Eugen Schiffer (until April 19, 1919) |

DDP | ||

|

Bernhard Dernburg (from April 30, 1919) |

DDP | |||

| economy | Rudolf Wissell | SPD | ||

| nutrition | Robert Schmidt | SPD | ||

| job | Gustav Bauer | SPD | ||

| Reichswehr | Gustav Noske | SPD | ||

| Traffic and colonies | Johannes Bell | center | ||

| post Office | Johannes Giesberts | center | ||

| treasure |

Georg Gothein (from March 21, 1919) |

DDP | ||

| Reich Minister without portfolio | Eduard David | SPD | ||

| Matthias Erzberger | center | |||

|

Georg Gothein (until March 21, 1919) |

DDP | |||

Individual evidence

- ↑ The German Empire. Andreas Gonschior: Election to the National Assembly in 1919

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: Weimar 1918–1933. The history of the first German democracy. Beck, Munich 1993 p. 70f.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h files of the Reich Chancellery. Weimar Republic. Scheidemann cabinet. Volume 1, introduction II

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: Weimar 1918–1933. The history of the first German democracy. Beck, Munich 1993 p. 72.

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: Weimar 1918–1933. The history of the first German democracy. Beck, Munich 1993 pp. 72-74

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: Weimar 1918–1933. The history of the first German democracy. Beck, Munich 1993 p. 74f.

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: Weimar 1918–1933. The history of the first German democracy. Beck, Munich 1993 p. 75f.

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: Weimar 1918–1933. The history of the first German democracy. Beck, Munich 1993 pp. 78-82

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: Weimar 1918–1933. The history of the first German democracy. Beck, Munich 1993 p. 84f.

- ^ A b Heinrich August Winkler: Weimar 1918–1933. The history of the first German democracy. Beck, Munich 1993 p. 85

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: Weimar 1918–1933. The history of the first German democracy. Beck, Munich 1993 p. 87f.

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: Weimar 1918–1933. The history of the first German democracy. Beck, Munich 1993 pp. 89-91

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: Weimar 1918–1933. The history of the first German democracy. Beck, Munich 1993 p. 91

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: Weimar 1918–1933. The history of the first German democracy. Beck, Munich 1993 p. 92

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: Weimar 1918–1933. The history of the first German democracy. Beck, Munich 1993 p. 93

swell

- The Scheidemann cabinet - February 13 to June 20, 1919 , edited by Hagen Schulze, Boppard am Rhein (Haraldt Boldt Verlag) 1971 (= files of the Reich Chancellery, 1) online version

| predecessor | Government of Germany | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Cabinet Ebert | Scheidemann cabinet 1919 |

Cabinet peasant |