Kalevala

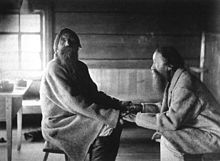

The Defense of Sampo .

This Kalevala illustration shows the hero Väinämöinen and Louhi , ruler of the northern country Pohjola , fighting for the magical item Sampo .

The Kalevala [ ˈkɑlɛʋɑlɑ ] is an epic compiled by Elias Lönnrot in the 19th century on the basis of orally transmitted Finnish mythology . It is considered the Finnish national epic and is one of the most important literary works in the Finnish language . The Kalevala contributed significantly to the development of Finnish national consciousness and has also had an impact beyond Finland . The first version of the work was published in 1835. The title is derived from Kaleva, the name of the forefather of the sung hero, and means something like "the land of Kaleva". The standard text of the Kalevala consists of 22,795 verses presented in fifty chants.

content

overview

The Kalevala is a compilation of different traditions and reflects a wide range of heroic sagas and myths . The main narrative thread is initially about the wooing of the daughter of Louhi , the ruler of the north country ( Pohjola ) , and is embedded in a conflict between the people of Kalevala and those of Pohjola over the sampo , a mythical object that provides its owner with wealth promises. Pohjola can be identified with parts of Lapland . Different interpretations have been suggested for the sampo, a magical device that makes gold, grain and salt. There are also several other storylines, for example the legend of Kullervo , who ignorantly seduces his own sister, or the Christian legend of Marjatta, i.e. the Virgin Mary . The traditions in Kalevala also include a myth about the creation of the earth and other myths about its origins, such as that of iron.

The main protagonist of the Kalevala is the old and wise singer Väinämöinen . It combines the traits of a legendary hero, a shaman and a mythical deity. Other central figures are the blacksmith Ilmarinen and the militant womanizer Lemminkäinen .

Some of the contents of the Kalevala show parallels to myths from other cultural areas. Kullervo is reminiscent of the Greek Oedipus myth. The story of Lemminkäinen, who was brought back to life by his mother from the river of death, shows strong parallels to the Egyptian myth of Osiris . The Kalevala differs from other saga cycles in that it focuses on the common people. The heroes of Kalevala are also distinguished less by martial skills than by knowledge and the art of singing.

Content according to chants

First Väinämöinen cycle

Canto 1 to 2: The Kalevala begins with the poet's opening words. A creation myth follows , which describes how the world emerges from the egg of a diving duck after Ilmatar breaks it. Ilmatar also gives birth to Väinämöinen .

Aino- Triptych

The first meeting of Väinämöinen and Aino is shown, her escape from Väinämöinen's advances and Aino when she decides to drown herself.

3rd to 5th chant: To save his life after a lost singing competition, Joukahainen Väinämöinen promises his sister Aino as a wife. Aino, feeling repulsed by the old man, fends off Väinämöinen's advances and drowns herself.

Canto 6 to 10: Väinämöinen travels to Nordland ( Pohjola ) with the intention of soliciting the Nordland daughter. On the way, Joukahainen, in revenge, shoots Väinämöinen's horse and the latter falls into the sea. An eagle rescues him there and carries him to the north. To get home, Väinämöinen promises Louhi , the ruler of the north, that the blacksmith Ilmarinen will forge her sampo . As a reward, the blacksmith is promised the Nordland daughter. After his return home, Väinämöinen conjures up Ilmarinen in the Nordland, where he forges the Sampo, but he has to return without the promised bride.

First Lemminkäinen cycle

11th to 15th song: Lemminkäinen steals Kyllikki from "the island" (Saari) as his bride. He leaves Kyllikki, travels to the north and asks Louhi for her daughter's hand, whereupon she gives him three tasks. After he has killed the moose from Hiisi and bridled the stallion from Hiisi, he is supposed to shoot the swan on the river of the Tuonela realm of the dead . A shepherd kills him at the river and throws the dismembered body into the river. Lemminkäinen's mother learns of her son's death through a sign, fishes the pieces of his body from the river with a rake and brings him back to life.

Second Väinämöinen cycle

Chant 16 to 25: Väinämöinen begins building a boat to sail to the Nordland and again free the Nordland subsidiary. In search of the magic spells required for this, he visits the realm of the dead unsuccessfully and finally finds out about them in the belly of the dead giant and magician Antero Vipunen. Ilmarinen learns of Väinämöinen's plans from his sister Annikki and also travels to the Nordland. The Nordland subsidiary chooses Ilmarinen. With their help, Ilmarinen completes the supernatural tasks he is given: he plows the snake field, catches the bear from Tuoni, the wolf from Manala and the big pike in the river of the realm of the dead. Ilmarinen marries the Nordland daughter.

Second Lemminkäinen cycle

Canto 26 to 30: Lemminkäinen is angry that he was not invited to the wedding and travels to the north country, where he kills the lord of the north country. He has to flee and hides on the island, where he has fun with the women until the jealous men drive him away. When he returns home, he finds his house burned down. He goes on a vengeance to the Nordland, but has to return home without having achieved anything.

Kullervo cycle

Chant 31 to 36: Untamo defeats his brother Kalervo after a quarrel and kills all of his sex except for a pregnant woman who gives birth to Kullervo . Untamo sells Kullervo as a slave to Ilmarinen. Ilmarinen's wife makes him work as a shepherd and treats him badly. In revenge, Kullervo drives the cows into the swamp and instead drives a herd of predators home. Ilmarinen's wife is killed by the wild animals. Kullervo flees the Ilmarinen's house and finds his parents, who were believed dead. Without realizing her, he unwittingly seduces his sister. When she finds out, the sister drowns herself in a rapids. Kullervo moves to Untamo's house to get revenge. He kills everyone there and returns home where no one is alive. Kullervo commits suicide by throwing himself on his sword.

Ilmarinen cycle

Chants 37 to 38: Ilmarinen mourns his dead wife and forges a new woman out of gold. The golden bride is cold and Ilmarinen rejects her again. Thereupon he woos unsuccessfully for the younger daughter of the north country. After his return home, he tells Väinämöinen about the prosperity that the Sampo brings to the people of the Nordland.

Third Väinämöinen cycle

Chants 39 to 43: Väinämöinen, Ilmarinen and Lemminkäinen sail to Nordland to steal the Sampo. On the trip, Väinämöinen kills a huge pike and builds a kantele from its jaw . He puts the northerners to sleep with his kantelespiel. Väinämöinen and his companions flee with the sampo. After she wakes up, Louhi turns into a giant eagle and sets off with her army in pursuit. The sampo breaks during a fight.

Chants 44 to 49: Louhi sends diseases and a bear to Kalevala; she hides the stars and steals the fire. Väinämöinen and Ilmarinen regain the stars and fire.

Marjatta cycle

Chant 50: In a modification of the New Testament it is described how Marjatta ( Maria ) becomes pregnant by a cranberry . Väinämöinen sentences the fatherless child to death, but the child prevails against Väinämöinen and becomes King of Karelia. Väinämöinen leaves with his boat. The epic ends with the poet's closing words.

Language and style

meter

The meter used in the Kalevala was found in all types of Finnish folk poetry as well as in proverbs and the like. Ä. Use. Today it is commonly referred to as the Kalevala meter. Similar meters can be found among the Estonians and other Baltic Finnish peoples. It is believed to be over 2,000 years old. Since the publication of the Kalevala, the Kalevala meter has also been used in Finnish art poetry to this day.

The Kalevala meter differs in many ways from the meter measures of the Indo-European languages . It is a trochaic four-lifter , i.e. H. each verse consists of four trochaes, for a total of eight syllables. A trochee is understood as a sequence of uplift and downward movement. The basic rule of the Kalevala meter states the following:

- The initial syllable of a word must be long if it is in the accentuation of a verse . In the example verse, the relevant syllables are underlined:

- Vaka | van ha | Väi Nä | möinen

- The initial syllable of a word must be short in the lowering.

- tietä | jä i | än i | kuinen

Four additional rules also apply:

- In the first foot of the verse, the length of the syllables is free. It can sometimes (in around 3% of the verses of the Kalevala) consist of three or rarely even four syllables.

- A monosyllabic word cannot appear at the end of a verse.

- A four-syllable word cannot appear in the middle of a verse. (Does not apply to compound words.)

- The last syllable of a verse cannot contain a long vowel .

The verses are divided into "normal" verses, in which the word stresses (which in Finnish always lie on the first syllable of a word) and hyphenations coincide, and "broken" verses, in which at least one stressed syllable is in a lowering. About half of the Kalevala verses are broken. This counterpoint between word and verse rhythm is characteristic of the Kalevala meter. Normal verses have a middle caesura . Long words tend to come at the end of the verse.

When translating Kalevala into German or other accented languages , the system based on lengths and abbreviations is replaced by an accented meter. A trochaeus consists of a sequence of a stressed and an unstressed syllable (example: Väinä | möinen | old and | wise || er, the | eternal | magician | speaker .)

Stylistic devices

The two most important stylistic devices of Kalevala are alliteration ( alliteration ) and parallelism . Both arose from the need to make the orally transmitted poetry easily remembered.

Alliteration means that two or more words in a verse begin with the same sound (example Vaka vanha Väinämöinen “Väinämöinen old and wise”). A distinction is made between “weak” alliteration, in which two words begin with the same consonant or both with a vowel, and “strong” alliteration, in which two words begin with the same sequence of consonant and vowel or with the same vowel. This stylistic device occurs extremely often in the Kalevala: Over half of the verses show strong alliteration, around a fifth have weak alliteration. There are no end rhymes , however.

The parallelism can appear in different forms. Usually the content of a previous verse is repeated in the post verse in other words. Each word of the post-verse has a correspondence in the preceding verse. This correspondence can be synonymous (equivalent), analog (similar) or also antithetic (opposite). The parallelism can also occur within a verse, but sometimes it also includes longer passages structured according to the same scheme. In Kalevala, parallelism is used to an even greater extent than in folk poetry, which is probably related to Elias Lönnrot's desire to utilize as large a part of the material he has collected as possible.

Examples of parallelism:

- Lahme miekan Mittelöhön, / käypä kalvan katselohon "Let us look at the swords / let's measure the blades now" (synonymous)

- Kulki kuusisna hakona, / petäjäisnä pehkiönä " wanders like a branch of the spruce, / drifts like the dry rice of the fir" (analogue)

- Siitä läksi, ei totellut "Go anyway, ignoring anything" (antithetical)

Text example

Kalevala opening verses (1: 1–9)

|

|

Work history

The Kalevala goes back to the ancient orally transmitted Finnish folk poetry . The compilation of the songs into a coherent epic , however, dates back to the 19th century and is an art product by Elias Lönnrot . Based on Friedrich August Wolf's theory on the Homeric Question, Lönnrot himself was convinced of the (now obsolete) view that the many individual songs he had recorded on his travels in Karelia had once formed a coherent epic that needed to be reconstructed. He put the songs he had collected together and changed some of the contexts in order to combine them into a logical action. 33% of the verses of the Kalevala are taken verbatim from the collected records, 50% are slightly edited by Lönnrot, 14% of the verses he wrote himself analogous to existing verses and 3% he invented freely. Overall, the Kalevala can be described as his magnum opus .

Finnish folk poetry

The common tradition of orally transmitted folk poetry can be found in the entire Baltic Finnish- speaking area, i.e. in Finland , Karelia , Estonia and Ingermanland . It is believed that this type of seal originated between 2500 and 3000 years ago. The songs called "runes" ( Finnish runo ) were sung according to certain, quite simple melodies, sometimes accompanied by a kantele . In areas where the folk poetry tradition was still alive, the majority of people knew at least some songs. There were also wandering rune singers who could recite a large repertoire of runes by heart.

Folk poetry was widespread throughout Finland until the 16th century. After the Reformation , the Lutheran Church banned the “ pagan ” runes, and the tradition gradually dried up in western and central Finland. In the Orthodox East Karelia , which belongs to Russia , folk poetry could last longer. The tradition stayed alive until the early 20th century, today there are only a few old people who have mastered the old songs.

Finnish folk poetry is divided into three main branches: epic , lyric and incantation . The epic includes layers of different ages. The oldest layer is made up of mythical runes that deal with the creation of the earth. Myths of origin such as the origin of iron have their origin in shamanism of the pre- Christian period, i. H. before the 12th century. During the Middle Ages , heroic poetry and ballads were created, as well as - after the conversion of the Finns - legends with a Christian theme. In later times the epics dealt with historical events such as the murder of Bishop Heinrich von Uppsala , who as the patron saint of Finland is a core part of Finnish national mythology, or the wars between the Swedish Empire and Russia . Poetry includes runes on special occasions (e.g. wedding, killing a bear), songs that were sung in everyday life (e.g. when working in the fields), love poetry and elegies . The incantation songs come from pre-Christian magic . With magic spells one tried to conjure up the healing of illnesses or hunting luck. The action of the Kalevala is based on a compilation of various epic themes, alongside lyrical or magical runes are incorporated in appropriate places.

Origin of the Epic

A few songs had been recorded as early as the 17th century, but real scholarly interest in Finnish folk poetry did not emerge until the late 18th century. Among other things, Henrik Gabriel Porthan , the most important Finnish humanist of his time, recorded folk songs and published De Poësi Fennica ("On Finnish Poetry") from 1766–1778 . One from the recorded runic the idea of epic along the lines of the Iliad and the Odyssey or the Nibelungenlied to create, formulated in 1817 the first Fennomane Carl Axel Lund God (similar to 1808 August Thieme ). The fulfillment of this task should ultimately fall to the philologist and doctor Elias Lönnrot . Between the years 1828 and 1844 he made a total of eleven trips, mainly to Karelia , to collect source material. He recorded large amounts of material from runesingers like Arhippa Perttunen . The villages Lönnrot visited (including Uchta (Uhtua), which was renamed Kalewala in 1963, as well as Woknawolok (Vuokkiniemi) and Ladwaosero (Latvajärvi)) belonged to Russia then as now.

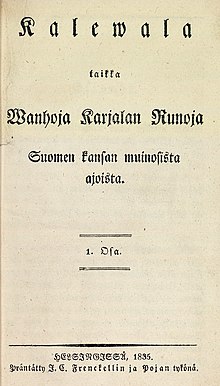

In 1834, Lönnrot published the runokokous Väinämöisestä (“Runic collection about Väinämöinen”), a kind of “Proto-Kalevala”, based on the material he had collected . It marks a turning point in Lönnrot's work. While he had previously dealt with the material in a scientific and text-critical manner, the focus was now on artistic intention for the first time. 1835-1836 Elias Lönnrot published the so-called "Old Kalevala", which comprised 32 runes with 12,078 verses. The “New Kalevala”, which was supplemented by numerous material and with 50 runes and 22,795 verses, almost twice as long, was published in 1849 and is now the standard text.

The Kanteletar collection of poems is considered a “sister work” of the Kalevala . It was published by Elias Lönnrot in 1840 on the basis of the same source material from which he had compiled the Kalevala.

expenditure

The first version of Lönnrots Kalevala appeared in two volumes from 1835 to 1836 under the title Kalewala, taikka Wanhoja Karjalan Runoja Suomen kansan muinoisista ajoista ("Kalevala, or ancient runes of Karelia about ancient times of the Finnish people"). The “birthday” of the epic is February 28, 1835 , the day on which Elias Lönnrot signed the foreword to the first volume. Today, February 28, Finland celebrates Kalevala Day. The "new Kalevala" appeared in 1849 with the simple title Kalevala . Since then, the epic has appeared in dozens of different Finnish-language editions. In addition, numerous abstracts, versions for school lessons, prose retellings and adaptations for children have been published. The Kalevala has been translated into 51 languages, including Low German , Latin and exotic languages like Fulani .

meaning

As a national symbol

The importance of the Kalevala for Finnish culture and the national feeling of the Finns is much greater than that of most other national epics . The political dimension of the Kalevala is in some cases so high that it is claimed that Finland has become an independent nation precisely because of the Kalevala. At the time the Kalevala was published , a new Finnish identity was emerging in Finland, fueled by the idea of nationalism that had emerged in Europe . The Kalevala contributed significantly to their development. Up until then there was no independent Finnish written culture , but with the existence of a national epic in the rank of Edda , Nibelungenlied or Iliad , the Finns saw themselves as part of the group of civilized peoples . This view was reinforced by the attention that the Kalevala also received abroad. The Finnish national movement wanted to make up for the country's lack of history by attempting to interpret the Kalevala as a historical testimony to the “primeval times of the Finnish people”. At the same time, the publication of Kalevala strengthened the role of the Finnish language , which had not previously been used as a literary language. In 1902 it was introduced as an official language alongside Swedish . The "national awakening" of Finland, for its part, played a part in gaining state independence in 1917.

In today's Finland

The influence of Kalevala can still be felt in Finnish social life today. Well-known passages of the Kalevala are often quoted; so a difficult task with allusion to the deeds of the Ilmarinen can be described as “plowing the snake field”. First names like Väinö, Ilmari, Tapio or Aino go back to the characters of the epic. Numerous companies have chosen names related to the Kalevala theme: there is a financial company “ Sampo ”, an insurance company “ Pohjola ” and an ice cream brand “Aino”. The company Kalevala Koru , one of the most famous jewelry manufacturers in Finland, owes its name and existence to the epic; A memorial for the women mentioned in the Kalevala was to be financed with the proceeds of an association of the "Kalevala women", from which the jewelry manufacturer emerged. New development areas such as Kaleva in Tampere or Tapiola in Espoo were named after terms from the Kalevala.

reception

The Kalevala has shaped Finnish culture in a way that should not be underestimated and has become an inspiration for numerous artists. The fact that the most important works on Kalevala did not emerge until the end of the 19th century, i.e. many decades after the epic was published, is due to the fact that art in Finland was still in its infancy in Lönnrot's time. The two decades between 1890 and 1910 are considered the “golden age” of Finnish art. During this time the enthusiasm known as Karelianism for Kalevala and its place of origin Karelia developed . Almost all of the major Finnish artists of this era made trips to Karelia and were inspired by the Kalevala.

literature

The cycle of poems Helkavirsiä (1903–1916) by Eino Leino , written in Kalevala meter, combines Karelianism with European symbolism . The writer Juhani Aho also occupied himself a. a. in his novel Panu (1879) with the Kalevala. Aleksis Kivi wrote the play Kullervo , which premiered in 1885. Paavo Haavikko's Kullervon tarina (1982) is also a theater adaptation of the Kullervo cycle .

The epic has also had an impact outside of Finland. Friedrich Reinhold Kreutzwald collected folk poetry in Estonia and created the Estonian national epic Kalevipoeg based on the model of the Kalevala . The American Henry Wadsworth Longfellow adopted the Kalevala meter for his epic poem Song of Hiawatha, which is based on Indian legends . JRR Tolkien processed numerous influences from the Kalevala in his work.

Visual arts

Väinämöinen attaches the strings to his kantele (1851) by the Swede Johan Blackstadius is the first Kalevala painting. In the following years, RW Ekman , the leading Finnish artist of his time, dealt with the subject. For the next few decades, however, Kalevala art dried up. Only in the 1880s did it experience a renaissance with the emergence of a new generation of artists and the rise of Karelianism. The most famous paintings on the Kalevala are by Akseli Gallen-Kallela . His illustrations are very well known in Finland and shape the idea of the national epic. While his early work can be attributed to realism , he was later influenced by symbolism and art nouveau . His most important works are The Defense of Sampo (1895), Joukahainen's Revenge , Lemminkäinen's Mother (both 1897) and Kullervo's Curse (1899). Also Pekka Halonen , another important representative of Karelianism, dealt with the Kalevala, although only marginally. Emil Wikström takes on a role similar to that of Gallen-Kallela in painting in the field of sculpture .

The architect Eliel Saarinen designed the Finnish pavilion for the 1900 World Exhibition in Paris , which Gallen-Kallela decorated with ceiling frescoes depicting scenes from the Kalevala. The National Museum (1911) and the Central Station (1919) in Helsinki , both also designed by Saarinen, are examples of the nationally romantic, Kalevala-inspired Finnish architecture of that era. Saarinen also planned a Kalevala house, which was intended as some sort of Finnish cultural heritage site, but was never realized.

The photographer IK Inha traveled to Karelia in 1894 to follow Elias Lönnrot's footsteps to document life in the villages in which the Kalevala was created. His portraits and landscapes have been used in many publications on Finnish folk poetry. The first film adaptation of Kalevala was the Finnish-Soviet co-production Sampo (1959). In 1982 the four-part television film Rauta-aika was made .

music

The first major orchestral works on the Kalevala theme were composed by Robert Kajanus in the 1880s . The composer Jean Sibelius was led to Karelianism by Kajanus' influence. In 1892 he composed the symphony Kullervo after a trip to Karelia . The Lemminkäinen Suite followed between 1893 and 1895, which contains the symphonic poem The Swan of Tuonela . Other well-known Kalevala works by Sibelius are the symphonic poems Pohjola's Daughter (1906) and Tapiola (1926). Leevi Madetoja wrote the symphonic poem Kullervo op.15 in 1913 .

Among the contemporary Finnish composers, Einojuhani Rautavaara took up the Kalevala theme in his work The Rape of Sampo (1982). 1992 was the opera Kullervo by Aulis Sallinen in Los Angeles premiered.

The Finnish metal band Amorphis released several successful albums whose lyrics are based on the Kalevala: Tales from the Thousand Lakes (1994), Eclipse (2006), in which the Kullervo cycle is set to music, Silent Waters (2007), which is the first Lemminkäinen Cycle narrated, Skyforger (2009), as well as The Beginning of Times (2011). The Finnish folk metal bands Ensiferum and Turisas also deal with this topic.

Movie

1959 appeared as a Finnish-Soviet co-production of the film “Sampo” (German version: “The stolen happiness”). With the usual pathos and naivety of the time, the film tells the fight between the Kalevala heroes and the witch Louhi. The cinematic stylistic devices used are reminiscent of Soviet films “for the moral follow-up” of the war ( Great Patriotic War ) such as Ilja Muromets (Mosfilm 1956). In this respect, the film gives more information about the circumstances at the time of its creation than about the Kalevala epic, but it makes the viewer well acquainted with the characters. " Jade-Krieger " (German title, Finnish: "Jade Soturi") is a Finnish-Chinese production published in 2008 that is based on the mythology of Kalevala. In 1985 the four-part film "Die eiserne Zeit" (The Iron Age) was shown on GDR television, based on motifs from the Kalevala epic, which vividly illustrated the problems of this work.

theatre

The play Zaubermühle by the author Katrin Lange is based on motifs from Kalevala. The world premiere took place on January 21, 2015 in the Schnawwl Theater Mannheim.

Popular culture

The American comic artist Don Rosa published the Donald Duck comic The Quest for Kalevala (German title Die Jagd nach der Goldmühle ), in which Dagobert Duck tries to find Sampo and meets numerous Kalevala characters (including Väinämöinen and Louhi) . A picture book adaptation for children is Koirien Kalevala ("Dog Kalevala") by the Finnish children's book author Mauri Kunnas . In both works, scenes from Akseli Gallen-Kallela's Kalevala illustrations are traced.

swell

- ↑ a b c d German translation after Anton Schiefner and Martin Buber .

literature

Text editions / audio books / edits

- Kalevala. The Finnish epic by Elias Lönnrot. Transferred from the Finnish original by Lore Fromm and Hans Fromm. With a post by Hans Fromm. Marix Verlag, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-86539-013-7 .

- Elias Lönnrot : Kalevala. The Finnish National Epic (audio book) , 4 CDs with illustrations by Carola Giese . Michael John Verlag , 2015, ISBN 978-3-942057-57-8 .

- Kalewala. The Finnish epic by Elias Lönnrot. Translated and with an afterword by Gisbert Jänicke. Jung und Jung, Salzburg / Vienna 2004, ISBN 3-902144-68-8 (new translation).

- Inge Ott: Kalevala. The deeds of Väinämöinen, Ilmarinen and Lemminkäinen. Newly told by Inge Ott. With illustrations by Herbert Holzing. Free Spiritual Life Publishing House, Stuttgart 1978, 1981, 1989, ISBN 3-7725-0697-6 (prose retelling).

- Kalewala, the national epic of the Finns , translated into German by Anton Schiefner after the second edition. J. C. Frenckell & Son, Helsingfors 1852.

- Kalevala. The national epic of the Finns. Hinstorff, Rostock 2001, ISBN 3-356-00792-0 (partial edition).

- Pertti Anttonen, Matti Kuusi: Kalevala-lipas. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, Helsinki 1999, ISBN 951-746-045-7 .

- Kalewala. Markus Hering reads from the Finnish epic by Elias Lönnrot. Jung und Jung, Vienna 2005, ISBN 3-200-00474-6 (audio book based on the translation by Gisbert Jänicke; music compilation by Peter Kislinger; 4 audio CDs).

- Tilman Spreckelsen : Kalevala. A legend from the north , retold by TS and illustrated by Kat Menschik . Verlag Galiani Berlin, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-86971-099-0 .

Secondary literature

- Christian Niedling: On the importance of national epics in the 19th century. The example of Kalevala and the Nibelungenlied. Cologne 2007, ISBN 978-3-939060-05-5 .

- Harald Falck-Ytter: Kalevala. Earth myth and future of humanity. Mellinger Verlag, Stuttgart 1993, ISBN 3-88069-301-3 .

- Wilhelm von Tettau : About the epic poems of the Finnish peoples, especially the Kalewala. Erfurt: Villaret 1873.

- Kalevala. The Finnish epic by Elias Lönnrot. Reclam, Stuttgart 1989, ISBN 3-15-010332-0 (German edition).

- Elemér Bakó: Elias Lönnrot and his Kalevala , 1985, Bibliography, Library of Congress.