Kingdom of the Congo

| Congo dya Ntotila Wene wa Congo |

|||||

| Kingdom of the Congo | |||||

|

|

|||||

| Official language | Kikongo | ||||

| Capital | M'banza Congo | ||||

| Form of government | monarchy | ||||

| Head of state , also head of government |

Mani-Congo (King) most recently Kimpa Vita |

||||

| surface | 129,400 (1650) km² | ||||

| population | 509,250 (1650) | ||||

| currency | Nzimbu and Raffia | ||||

| founding | 14th Century | ||||

| resolution | 18th century | ||||

| Kingdom of the Congo in the borders around 1711. At this point in time, the kingdom was on what is now Angola, the DR Congo and the Republic of the Congo | |||||

The Kingdom of Congo (in Kikongo : Kongo dya Ntotila or Wene wa Kongo ) was a Bantu empire in central Africa from the 14th to the 18th century.

At the time of contact with the Portuguese, it covered around 300,000 km² across parts of what is now Angola (three quarters of the area), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (one quarter) and the Republic of the Congo (around 1%). The Kingdom of the Congo was, alongside the Kingdom of Lunda , the most important Central African state of its time.

State organization

Administrative structure

The empire was initially divided into the levels of province , district and village and divided into the six provinces Mpemba, Nsundi , Mpangu , Mbata , Mbamba and Soyo . With the contractual integration of the states of Kakongo , Loango and Ngoyo , a federation of four sub-states was later created, only the sub-state of the Congo remained directly under the Mani Congo , the further structure remained unchanged.

The basis of the administrative structure was the village, the management of which was hereditary and matrilocal . The management level of the village did not have a formal title and was therefore not part of the aristocracy of the empire. The districts as the level above the villages were each headed by an officer who was appointed either by the governor of the province or the Mani Kongo itself and who could be recalled at any time. In addition to administrative tasks, these officials also acted as judges in the districts. Some districts, for example the Wembo district in the south, were directly subordinate to the Mani Congo, but most were integrated into one of the six provinces. The officials of the provinces were appointed by the Mani Kongo, who were mostly also its advisors. In addition, at the provincial level, they basically performed the same tasks as the district officials.

monarchy

The Mani Kongo originally emerged from the descendants of the founding father Ntinu Wene and from 1540 from those of Afonso I from a committee of nine to twelve electors (among them the Mani Soyo, the Mani Mbata and the Mani Kabunga, who had the right of veto ) selected a few exceptions from either the Kimpanzu or Kimulazu clan. The aspirants to the throne began to build up a support network years in advance, and the strongest faction was mostly confirmed by the election committee. The supporters of the new Mani Congo were then rewarded with offices at provincial or district level. The Mani Kongo was joined by the twelve-member Ne Mbanda council , which had the right to veto important decisions such as the appointment of civil servants, the declaration of wars and the opening and closing of roads. From 1512 a Portuguese adviser was added to these, after 1568 the royal confessor took his place.

The Mani Kongo sat on a throne made of wood and ivory ; the insignia of his power were a whip made from the tail of a zebra , a belt hung with fur and animal heads, and a small cap. His subjects had to approach him on all fours and were not allowed to watch him eat or drink; if they did, they faced the death penalty.

Social and legal structure

All officials from the district level onwards had the title Mani (or in the north of the empire Ne ), followed by the name of the district or province for which they were responsible, for example Mani Wembo, Mani Mpemba and Mani Kongo (responsible for the Empire). Together with the officials at the court, who also bore the title Mani, supplemented by a description of their function, the Manis formed the aristocratic class . They were the only ones who had the privilege of forging iron, as the state's founder, Wene, had been a blacksmith.

In addition to the nobles and “normal” citizens, there were also slaves , through captivity, indebtedness, punishment or as family dowry payments. Similar to ancient Rome or Greece, the slaves could regain their freedom here or marry free ones. This is in contrast to the later slave policy of the Europeans . Most judicial positions were part of the offices of the Manis, from district to state level. The chief judge and specialist in adultery cases was Mani Vangu Vangu, a resident of the royal court.

In the 17th century , the upper class , unlike the simple population, was strongly Europeanized.

military

Apart from a royal bodyguard , there was originally no standing army in the Congo . If necessary, a people's army was called together. The level of organization of this untrained army was low, although there were military titles ( Tendala , Ngolambolo ), but no detailed knowledge of strategies or tactics. Wars were decided by individual battles, as there was no supply system that could supply armies for long periods of time. In 1575, two standing military formations equipped with arquebuses were brought into being. One served as the king's new bodyguard, and another was stationed at Mani Mbata. At this time there were also tactical developments.

In the 17th century there was a standing army of 5,000 soldiers, including 500 musketeers .

economy

Finances

The state's income consisted largely of taxes and labor services (similar to the European fron ). The state also received tributes in kind (raffia fabric, ivory, millet, slaves), customs duties and fines. The entire state income was monitored by a body called Mfutila together with the Mani Mpanza and the Mani Samba, and it was mostly used to support the royal court, but also smaller manis courts at provincial and district level.

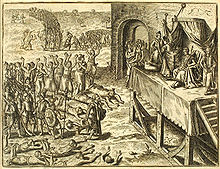

Taxes were paid once a year in ritual form, since 1506 at the festival in honor of James the Elder on July 25th. The handover ceremony took place in front of the palace of Mani Kongo. The Manis of the districts and provinces stepped forward individually, handed over the taxes and renewed their oath of allegiance for another year. Depending on his satisfaction, the Mani Kongo confirmed her for another year or removed her from office.

A unique feature was the complete control of the currency by the Mani Kongo. On the island off the coast of Luanda , mussels were found whose shells ( nzimbu ) were used as money. The island belonged to the Mani Congo and mussel fishing in its waters was its privilege. The resulting opportunities for a consistent fiscal policy remained unused, however, and the currency was constantly inflationary .

Economics and trade

As in most of the Central African savanna states, agriculture in the Congo was based on slash-and- burn shifting cultivation , inefficient and only suitable for subsistence farming . Grown beans , sorghum , millet , cowpea and other classic African vegetables, increasingly introduced from South America or Asia since the 16th century crops such as cassava , corn , peanuts , sweet potatoes , yams or bananas , occasionally also sugar cane . To obtain textile raw materials were raphia palms cultivated. In addition to the processing of iron , copper was also processed. The extraction of iron has been proven since the 4th century BC.

As pets were chickens , goats and dogs spread since the 18th century, pigs and ducks . Sheep were also common, but they were often subject to taboos . Only a few cattle are found , mostly owned by Manis. Markets took place at regularly changing locations. There were no professional traders; the producers offered their surpluses themselves.

Since the 14th and 15th centuries, trade between the coast and inland was one of the foundations of the empire's economy.

calendar

As in many regions of West and Central Africa, a calendar based on the four-day week applied in the Congo Empire . The following applied: 1 week comprised 4 days, the month comprised 7 weeks and the year comprised 13 months plus 1 day. With the adoption of Christianity, the Christian calendar increasingly supplanted the use of this calendar.

religion

The original religious ideas of the people of the Congo Empire share their foundations with those of the surrounding peoples, but have some special features. As everywhere in the savanna states of Central Africa, there was a creator god. As a spiritual figure, this was considered to be directly accessible to every individual, in contrast to the nature spirits (only worshiped north of the Congo River) and fetishes (a belief that can only be found south of the Congo River), which could only be reached by elders or priests. In the Congo, as everywhere in western central Africa, there was also a belief in witchcraft and sorcery. Almost only in the Congo, on the other hand, the ancestor cult was widespread as a special feature ;

history

Empire founding

The Congo Empire emerged around 1400. The founding father was supposedly Ntinu Wene, traditionally also called Nimi a Lukeni , who left his father's territory around Bungu, near today's city of Boma .

The establishment of the empire marked the beginning of his conquest of the Congo plateau, populated by Ambundu and Ambwela peoples, around the later capital M'banza-Congo . By marrying a woman from the Nsaku Vunda clan (who owned the spiritual rights on the land) and the ritual recognition by the Mani Kabunga, who as Kitomi (earth priest) administered the rights to the land, Wene consolidated his position and assumed the title of ruler Mani Kongo or Ne Kongo.

From this base, Wene subjugated the later provinces of Mpemba , Nsundi , Mbamba and Soyo in quick succession , two kingdoms located in the east on the Inkisi were also captured, Mpangu through a campaign of the governor of Nsundi and Mbata through the voluntary submission of Mani Mbata, who thereby remained in office as governor (his office also remained hereditary). The kingdoms of Kakongo , Loango and Ngoyo , which were independent at that time , were contractually incorporated into the empire. In his second conquered area, the province of Mpemba, Wene founded the settlement M'banza-Congo (in German " Königshof Congo ", renamed São Salvador in colonial times ) on today's border with the DR Congo in Angola . It remained the capital of the empire for the rest of its history.

The contact with Portugal

A Portuguese expedition sent by Diogo Cão after first reaching the mouth of the Congo in 1482 led to the first European contact with the king in M'banza-Congo in 1489. The incumbent Mani-Congo Nzinga, son of Nkuwu, sent an emissary to Portugal in return, was baptized as João I as early as 1491 (however, he fell away from the new faith in 1493 or 1494) and received military help from the Portuguese in return that helped consolidate its regional supremacy.

After Nzinga á Nkuwu's death, there was a power struggle between the Christian Mwemba and his traditionally religious brother Mpanzu, who did not accept the election result. In the "Battle of M'banza Kongo" Mwemba was able to prevail against his brother, but according to legend only with the "assistance of God" in the form of armed horsemen who appeared from heaven. As Dom Afonso I, Mwemba took control of the Congo in 1506.

Afonso I. and the Manuels Regimento

Afonso I was born around 1456 and ruled the Congo for 37 years, longer than any other ruler before or after him. As a devout Christian ruler, he pursued a policy of selective modernization closely based on Portugal. He understood the European great powers as Christian brother states, began to build up a local clergy, sent students to Europe and tried to bring European craftsmen and academics to the Congo. His hope was to be permanently recognized by the Portuguese and his royal comrade Manuel as an equal through forced Christianization and cooperation , a strategy that was initially successful. Portugal recognized the Mani-Congo (in contrast to all other European royal houses) as a king , even if (for formal reasons) not as a " highness ".

In 1512 there was the so-called “Regimento” of Manuel, an instruction to his ambassador that complied with Afonso's intentions. It stipulated that the Portuguese should stand by the Mani-Congo in the organization of its empire, including the establishment of a legal system based on the European model and an army. Missionary engagement, support in building churches and teaching the court Portuguese etiquette were also planned; in return, the Congo should fill the Portuguese ships with valuable cargo, in Manuel's letter with a specific request:

“ This expedition cost us a lot, it would be wrong to send you back home empty-handed. Although our primary wish is to serve God and please the Mani-Congo of the Congo, you should nevertheless make it clear to him on our behalf what he has to do to fill the ships, be it with slaves, copper or ivory . "

Again and again, however, Afonso had to see himself disappointed shortly after his enthronement. Above all, the behavior of the missionaries, which he perceived as greedy and "shameless", and the slave trade organized by the Portuguese, which no longer made a distinction between "normal" slaves, free people or even nobles, led him to several letters to the Portuguese king and even sent emissaries to the Vatican to deal with the problem.

There, however, he was not heard and in 1526 restricted the power of Portugal by expelling the Portuguese from the country, a request that missionaries and officials did, but not the slave traders. At that time the kingdom exported 2,000–3,000 slaves a year, which of course also brought material advantages for the kingdom and numerous middlemen. While Portugal shifted its interests to the south of the Congo Empire in response - with the founding of the fortified trading city of Luanda in 1575, the occupation of the immediate hinterland, the establishment of relations with the kingdoms of Matamba and Ndongo - the Congo gradually declined as it was economically and had long since become structurally dependent on Portugal.

The breakup and destruction of the empire

After Afonso's death in 1543, he was supposed to be succeeded by Pedro I, who was ousted by Afonso's grandson, Diogo I, in an immediately following dispute over the succession to the throne. Although originally rather hostile to Portugal, Diogo invited missionaries back into the country in 1546.

An attack in 1569 by the Jaga, either a people from today's Tanzania or possibly an alliance of rebellious peasants and an external power, could not withstand the empire, which had become unstable inside, on its own. These Jaga succeeded in taking the capital; the ruling clan under Alvaro I was only able to relieve them with Portuguese help.

But this liberation was a Pyrrhic victory; Álvaro I. had to go into the vassal service of Portugal and the Congo became tributary. Formally, with this step, the equality and equality of the two kingdoms ended. Alvaro's desperate act stabilized the Congo inside though and then tried Álvaro to redissolve from the grip of Portugal, but this failed and so Álvaro I. ultimately Portugal opened the way to get out of the Congo a hub for the expanding slave trade to make . This led to the depopulation of entire areas and let the Congo Empire gradually fall apart, especially after the death of Álvaro II in 1614, when Álvaro III. the outbreak of civil wars, uprisings and rebellions was unable to master, especially since he and his successors had to move in a network between Portugal, the new power Spain and the Dutch, who were fighting for their independence.

It was only Garcia II (Garcia II Nkanga a Lukeni a Nzenze a Ntumba, also Garcia Afonso) tried from 1641 to 1661, in an alliance with the Netherlands , to oppose the increasingly excessive slave trade and Portuguese domination. In 1665 the Portuguese provoked António I, until he declared all contracts concluded with Portugal to be invalid and demanded the return of all areas annexed by Portugal. The aim of the Portuguese provocations was to gain access to the copper deposits.

In the following battle of Ambuila (Ambwila), a Portuguese army defeated the Congolese army in 1665. This defeat would herald the final fall of the Congo Empire. António was beheaded, as were many of his courtiers (including the court priest and writer Manuel Roboredo ). Portugal took final control of the country, which, due to the lack of a central authority, was divided into its individual provinces, of which the northern ones kept less and less in contact with the rest.

Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita tried to revive the empire at the beginning of the 18th century. To do this, she used a synthesis of Christian and local religious motifs and claimed that she was a revenant of St. Anthony. Her rural supporters helped her to be temporarily installed as ruler in São Salvador, but in 1706 she was burned at the stake.

From 1718 the cohesion within the remaining provinces, in which the smaller units ("chiefdoms") took over the function of self-regulation, also loosened. The Congo Empire in its original form had ceased to exist after a little over 300 years, but was still considered to exist.

Since the re-emergence of a king in 1793, however, the office has continued to exist as an ethnic and cultural institution to the present day. Although no incumbent has been confirmed by the state since 1962, it seems that Dona Isabel Maria da Gama, widow of António III, is currently the incumbent regent; she would also be the first female incumbent. However, some sources report that their rule ended in 1975.

The Kingdom of the Congo gave its name to two modern states: the Republic of the Congo and the Democratic Republic of the Congo . For the history of the latter, see History of the Democratic Republic of the Congo .

literature

- Bernd Ludermann (Ed.): Congo - history of a battered country , "Weltmission heute 55 - country booklet", Hamburg 2004, ISSN 1430-6530 , (very good overview of the history, culture and society of the Congo)

- Jan Vansina: "The Kingdoms of the Savanna", 1966

- B. Lukács: On A Forgotten Kingdom

- Peter N. Stearns (Ed.): The Encyclopedia of World History: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern , Boston, 2001, http://www.bartleby.com/67/363.html , http://www.bartleby. com / 67 / 869.html , http://www.bartleby.com/67/885.html (accessed November 12, 2004)

- Adam Hochschild : Shadows over the Congo - The story of an almost forgotten crime against humanity , Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3608919732 , (Mainly on Leopold's reign and its end)

- Wyatt MacGaffey: Crossing the River: Myth and Movement in Central Africa , International symposium Angola on the Move: Transport Routes, Communication, and History, Berlin, 24. – 26. September 2003, online as PDF

- Georges Balandier: Daily life in the Kingdom of the Congo: From the sixteenth to the eighteenth century. 1968.

- António Custódio Gonçalves: A história revisitada do Kongo e de Angola , 2005.

- Anne Hilton: The Kingdom of Congo , 1985, ISBN 0198227191 .

- John K. Thornton: The Kingdom of Kongo: Civil War and Transition, 1641-1718 , 1983, ISBN 0299092909 -

- John K. Thornton: The Kongolese Saint Anthony: Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita and the Antonian Movement, 1684-1706 , 1998, ISBN 0521596491 .

- John K. Thornton: The origins and early history of the Kingdom of Congo, c.1350-1550 , International Journal of African Historical Studies 34: 89-120, 2001.

- Elise LaRose: Kongo, Kingdom , in: Religion Past and Present , 4th, completely revised. Ed., Vol. 4, 2001, 1577–1579, ISBN 3-16-146944-5 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ A b John Thornton: Demography and History in the Kingdom of Kongo, 1550-1750 . The Journal of African History, Vol. 18, No. 4, 1977, p. 526.

- ↑ European Institute for Political, Economic and Social Issues (Ed.): International Africa Forum . Volume 4, Weltforum Verlag, London 1968, p. 35.

- ↑ a b c John Iliffe : Geschichte Afrikas , Munich 2000, ISBN 3406463096 , p. 190.

- ^ John Iliffe: Geschichte Afrikas , 2000, p. 189, ISBN 3406463096

- ^ John Iliffe: Geschichte Afrikas , 2000, p. 50, ISBN 3406463096

- ↑ a b c John Iliffe: Geschichte Afrikas , 2000, p. 109, ISBN 3406463096

- ↑ Jan Vansina: "The Kingdoms of the Savanna", 1966, p. 24