Medieval cosmology

The cosmology of the Middle Ages is a picture of the world and its structure. The basics were taken from antiquity, especially the works of Plato , and later Aristotle and Ptolemy , and remained essentially unchanged until the end of the Middle Ages. In this cosmology, the globe stood immobile in the center of the cosmos. Around the earth and the three subsequent sublunar spheres of the elements were arranged the celestial spheres that carried the planets up to the outermost, invisible sphere in which the seat of God was assumed.

The medieval cosmos was basically divided between the sublunar world and the celestial spheres above. Except for their movements, the celestial spheres were understood as perfect and immutable. Change, error, imperfection and the like, on the other hand, were limited to the sublunar world, which in turn was made up of four element spheres. The earth itself was divided into four areas according to the model of the crate of Mallos , of which only one, ecumenism , was assumed to be populated. Europe, Africa and Asia were part of the ecumenical great continent.

From the 15th century onwards, the Cretan geography was increasingly questioned by the knowledge of the Portuguese navigators, the discoveries of another continent by Columbus and the circumnavigation by Magellan and finally overturned. The first to make public doubts about the finiteness of the celestial spheres was Giordano Bruno at the end of the 16th century, who understood the sun as a star among many and the fixed stars as suns with worlds inhabited by them, whereas his contemporary Johannes Kepler , for example, still of the fundamental correctness of the spherical worldview was convinced. The medieval image of the cosmos continued to have an impact far beyond its time, for example in that astronomy was still essentially understood as a theory of the geometry and kinematics of the universe until the late 19th century. This is also expressed in the naming of spherical astronomy . The preoccupation with the physics of celestial bodies was still considered to be far less important by conservative astronomers around 1900.

Sources of the medieval worldview

The foundations of the worldview originally derived from Plato's writings were accepted throughout the entire Middle Ages - including in the Islamic world. Plato's work was known in the early Middle Ages through the intermediate step of the Roman translation. Calcidius ' late antique translation of Plato's Timaeus was of particular importance for the worldview . In addition, the work of Macrobius was already known in the early Middle Ages , who passed on and commented on Ciceros Somnium Scipionis , Scipio's dream of building the cosmos, and the descriptions of the earth by the stoic philosopher Krates von Mallos . Since late antiquity, the worldview in the West has also been interpreted in terms of salvation history and based on the statements of the Holy Scriptures. Isidore of Seville summarized these sources in his encyclopedia, which became a standard work of the early and high Middle Ages.

As a result of a large movement of translation of Byzantine and Islamic manuscripts in the 12th and 13th centuries, additional works, especially by Aristotle and Ptolemy , came into the consciousness of the Latin West. Since these works contradict each other in their details, the translations were followed by a philosophical-scientific discussion , which, however, left the basis of the worldview, the spherical structure, untouched. Important participants in this discussion, which encompassed both the heavenly spheres and the sublunar world, were Johannes de Sacrobosco , Roger Bacon , Albertus Magnus , Thomas Aquinas, and Robert Grosseteste . In this discussion, cosmology is increasingly derived rationally from natural-philosophical arguments, i.e. that the sequence of the sublunar element spheres follows from the nature of the elements, that is, it is implicitly and not explicitly established by God.

Aristotle and Ptolemy give different models of planetary motion. Since the movement of the planets in the sky is not uniform, it cannot be explained by a single, invariably moving sphere. While Aristotle also assumed movable subspheres of the respective planetary spheres, Ptolemy started from the epicyclic model .

The heavenly spheres

The details of the celestial spheres were the subject of philosophical discussion in the Middle Ages, so no generally binding model beyond the basics can be given. The sequence and especially the number of spheres were disputed. This is all the more true after the 12th century, when other competing antique models became known.

The representation of the early medieval image of the planetary spheres can be found in Chalcidius in late antiquity. From the sublunar world, i.e. H. Seen from the earth, the first thing followed was the sphere of the moon and then that of the sun, the so-called luminous stars (translunar world). Above stood the lower planets Venus and Mercury, and then the upper ones; so Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. After Plato, only the sphere of fixed stars followed , the seat of the stars. Most scholars deduced from the Bible the existence of two other spheres outside the fixed star sphere. The crystal sphere was derived from Genesis, which speaks of “the waters above the earth and the waters below the earth”. The crystal sphere was interpreted as the heavenly waters and was considered to be the origin of all movement of the spheres below. The crystal sphere was often considered the seat of the blessed and saints. The tenth and outermost sphere that followed, Empyrean, was understood as the seat of God and angels.

Beda Venerabilis , on the other hand, gives a clearly different sequence of the "heavens" above the earth, which also in its number, seven, adhered more closely to biblical than to ancient models. First came air, then the “ ether ”. This was followed by a sphere that Bede called Olympus, which contained all the planets. Above it was the room of fire, the firmament of the fixed stars, the heaven of the angels and finally the heaven of the Trinity.

Johannes de Sacrobosco , on the other hand, followed the sequence of spheres favored by Aristotle. In his work de sphaera , written around 1220 , which became a standard textbook of the late Middle Ages up to the 17th century , he first named the moon, then Mercury, Venus and only then the sun and the upper planets. Almost all modern representations of the spherical worldview are based on this sequence. Campanus of Novara gave, also in the 13th century, the diameter of the Saturn sphere as 117 million kilometers. Given today's numbers for distances in the universe, this seems small. In fact, the value, then as it is today, is just as difficult to imagine or even grasp as the diameter of the Milky Way with a few tens of thousands of light years .

The planetary spheres were imagined as completely transparent shells, which consisted of a fifth element, the quintessence , and to which the respective planet was attached. The individual bowls moved against each other without friction.

The sublunar spheres

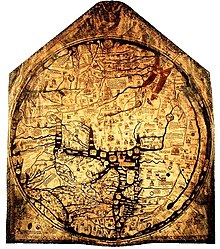

Below the sphere of the moon, according to the ancient and medieval worldview, there were four other spheres that consisted of the four elements . These sublunar elements have been referred to as air, fire, earth and water. In a widespread analogy, this model was called the “Weltei”, which accordingly consists of yolk, egg white, egg skin and shell. The elements are arranged according to their specific weight, i.e. at the bottom in the center of the earth, above water, above air and up to the sphere of the moon the fire. The sphere of the earth is not to be equated with the terrestrial globe according to today's understanding, it is rather a more or less regular sphere, which consists only of the element "earth". The ancient philosophers failed to explain how a dry surface of the earth on the innermost of the concentric spheres could be explained after this process. The thinkers of the early Middle Ages saw in this the creative work of God, who according to Genesis, as already mentioned above, divided the waters and placed the earth in between. The known area of the earth, the continents of Europe, Africa and Asia have been summarized under the term ecumenism . Often, as with Isidore of Seville , ecumenism was viewed as the only part of the earth that emerged from the waters. Some authors concluded that the earth sphere was eccentric to the water sphere, while others understood ecumenism as a bulge, i.e. a deviation from the spherical shape. According to the Christian understanding, Jerusalem was placed at the center of ecumenism in those maps, the mappa mundi , which represented ecumenism as a whole , around which the ecumenism was arranged in a circle . The map-makers were well aware of the actually deviating shape of the Okumene, which has more of a jacket-shaped shape. The circular shape with Jerusalem in the center became the standard for reasons of salvation history.

Alternatively, Krates of Mallos ' idea of the world was discussed, according to which the globe was assumed to be divided into four by two oceans. These oceans form two belts around the earth that intersect at right angles . The equatorial ocean was considered insurmountable because of the heat there. The polar ocean, identified in the west with the Atlantic and in the east with the Pacific, was often viewed as not crossable. According to this view, there were definitely other habitable areas of the world than ecumenism. In particular, the existence of the hypothetical antipodes was discussed. For reasons of salvation history, Augustine, for example, refused that the other major continents could be settled. For one thing, all humans descended from Adam, and since the oceans are impassable, the other continents could not have been colonized. On the other hand, Christ appeared in ecumenism, and the inhabitants of other continents would, again because of the impossibility of crossing the oceans, remain excluded from Christian salvation, which could not be in God's plan.

In the area of the sublunar spheres, too, the rediscovery of ancient writings in the 12th century made the doctrines subject to a revived discussion. In his Opus maius, Roger Bacon discussed the questions of the shape of the world and habitability and came to the conclusion that, although he acknowledges that there is no really certain knowledge about it, there is a narrow polar ocean, but it is not in principle insurmountable. These theses, summarized by Pierre d'Ailly , were used by Columbus to support his enterprise before the Talavera Commission . This commission had to deal not only with the question of the circumference of the earth, but also to discuss whether the earth and water spheres were eccentric or not. The latter would have doomed Columbus' plan to failure from the outset, since the extent of the water sphere would then have been significantly larger than the extent of the earth's sphere.

In addition to the geographical division by the world's oceans, the earth was divided into climatic zones, in which two models were followed. The first consisted of five climatic zones from the north to the south pole: the uninhabitable north polar zone, the temperate zone, the again uninhabitable equator zone, again a temperate zone and the south polar zone. On the other hand, only the ecumenical movement was often divided into seven or more climatic zones, which were equidistant in geographical latitude or were derived with the help of astronomical factors, such as the longest day of the year. Both models were taken from antiquity, whereby the geometric-astronomical climate zone model was more common in the Islamic world, the cratetic five-zone model in the West.

literature

- Evelyn Edson, Emilie Savage-Smith, Anna-Dorothee von den Brincken : The medieval cosmos . Primus, Darmstadt. ISBN 389678271-1

- Klaus Anselm Vogel: Sphaera terrae: The medieval image of the earth and the cosmographic revolution , 1995. Dissertation, Göttingen. on-line

See also

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ See BS Eastwood: Ordering the Heavens. Roman Astronomy and Cosmology in the Carolingian Renaissance. Leiden 2007.