Krazy cat

Krazy Kat is a comic strip by George Herriman that appeared in the newspapers of the publisher William Randolph Hearst between 1913 and 1944 - initially under the name Krazy Kat and Ignatz . The strip developed in its basic constellation mainly from the adventures of two speaking animal supporting characters in Herriman's humorous comic series The Dingbat Family (1910-1916). Herriman, who Krazy Kat claims to have invented out of boredom, drew the comic until his death in 1944.

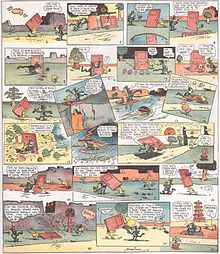

The focus of Krazy Kat is the cat Krazy, naive in the best sense of the word and gender indeterminable, who is in love with the cynical mouse Ignatz, even though the latter is constantly throwing bricks at her head to demonstrate his dislike. However, Krazy misinterprets every brick that finds its target as another token of love from her "little dahlink" (little darling) Ignatz, which only upsets him even more. To make matters worse, the policeman Offissa Pupp (German sergeant G. Kläff) is madly in love with Krazy and - to prevent further bricks from being thrown on Krazy's head - regularly puts Ignatz behind bars, lies in wait for him or at least confiscates his brick property.

development

Herriman drew and wrote about 20 different and sometimes very short-lived comic series between 1902, the year of his first comic book publication, and 1913 . As early as September 1903, a black cat appeared in the margins of the Lariate Pete series, which foreshadowed the later Krazy ( lit .: Blackbeard, 1991). This nameless, rather phlegmatic and good-natured cat appeared in several of Herriman's strips in the following years: in Bud Smith (1904), in Rosy's Mama and Zoo Zoo (both 1906), in Alexander and Baron Mooch (both 1909), and finally in The Dingbat Family (from 1910). In 1906 the cat begins to speak (although her appearances are still often only pantomime in nature); 1909 appears with an unnamed "duck-billed character" ( Lit .: Blackbeard, 1991) a first additional figure, which later under the name "Gooseberry Sprig, the Duck Duke" (Eng. "Entengrütz sprout, the Earl of Erpel") to permanent staff will be owned by Krazy Kat . This nameless duck, it is also that the cat (Engl. Cat ) in 1909 called for the first time "Kat".

In 1910, the "Cat" in true The Dingbat Family on a mouse that they (already on 25 September 1910 Ref : Blackbeard 1991) because of their strange behavior as "Krazy" (engl. Crazy , so crazy) respectively, and also a bulldog puppy shows up every now and then; the three frolic around, fight each other, make derisive comments and loudly pursue each other to the annoyance of the Dingbat family, under whose apartment they live. Sometime between 1910 and 1913 the mouse was given the name Ignatz, and the - completely contrary to what was expected - constellation of an aggressive mouse that chases a peaceful cat and throws various hard objects, at some point only bricks at its head, emerges. The supposed secondary characters, whose frolics are also attracting increasing attention from the Dingbat family, are so popular with the audience that they get their own one-line strip, which is printed under the adventures of the Dingbat family and which often refers directly to the plot refers what in dingbat happens -Strip above. From 1913 is on the pages of the New York Journal , an independent Krazy Kat -Tagesstrip be found ( Ref : Blackbeard, 1991). The last was published on June 25, 1944, exactly two months after Herriman's death.

Personnel and scenery

Between 1913 and 1916, when the Krazy Kat strips only appeared on working days in the form of one-liner made up of four, five or six connected panels , Herriman mostly concentrated on the absurd interaction of his main characters, cats and mice, with the occasional appearance of the young bulldog. But when, at the instigation of his admirer Hearst, on April 23, 1916, a first full-page story was also published in the Sunday edition of the New York Morning Journal , that changed quickly. On the expanded format, more complex narrative structures could be used, unusual graphical experiments could be made and more characters and locations could be introduced. From then on Herriman populated the Sunday strip with a myriad of other talking animals, some of which came from his older series, and invented an entire dusty, barren area of land, Coconino County (only loosely based on the county of the same name in the USA ), in as the home of his actors to which everything was possible both visually and narrative. The dog puppy became the cigar-smoking, adult Offissa B. Pupp (fully Officer Bull Pupp, literally translated as Constable Bulldog Puppy) overnight with a baton and prison - and thus reached the inextricably tricky love triangle that ultimately drove the Strip for almost thirty years their maturity. The previously cranky game of cat and mouse between the two main characters was raised to a higher level, as the bulldog as the third actor was given legal powers (arrest, surveillance, etc.) with which he could conceal his unacknowledged love for Krazy . Ignatz, who until now had only wanted to hit Krazy's head out of personal malice, became a cynical and increasingly tricky figure who had to constantly outsmart the arm of the law in order to be able to exercise her violent civil rights. The innocent creature Krazy, in turn, unintentionally got a permanent problem with Offissa Pupp, because he didn't really care about anything other than preventing Ignatz's lucky brick-throwing.

Poetry and surrealism

Herriman's Coconino County was a completely unpredictable location that was strongly reminiscent of a surrealistic stage with absurd props and backdrops that were also constantly changing. The moon in Krazy Kat sometimes looked like a gnawed melon skin and hung like a boat by strings from a sky, the texture of which changed from checkered to jagged and back, and the bizarre bushes, rocks and cacti sparsely distributed in the landscape changed from panel to panel their appearance. In a single panel, day and night could be combined quite casually, which greatly expanded the narrated time span within the picture. Often trees and cacti grew in pots; mesas and rocks often looked more like abstract, three-dimensional signs and by no means stony; often the vegetation was provided with strange (presumably Indian ) ornaments. From fleas to moths and bumblebees, ducks and coyotes to elephants, the entire animal world was represented in Coconino. The babies were brought by Joe Stork, whose arrival with the suspicious pouch everyone in Coconino feared; he lived high up on a secluded "enchanted mesa". One drank “tiger tea” and similar exotic drinks. The medium-sized brick manufacturer Kolin Kelly soon appeared with his loaded wheelbarrow in order to be able to consistently supply Ignatz with projectiles. Ignatz and Offissa Pupp were able to draw tree trunks themselves in the desert sketched by Herriman with a few strokes of ink, in order to hide behind them (an early example of questioning one's own drawing means in the comic strip). Krazy suddenly had relatives throughout the animal kingdom: Cousin Katzenvogel, Cousin Katzenfish, etc., whom she (or he) kept asking for advice and help. Ignatz, who insisted on his civil liberties, got a family that consisted of a resolute wife and three mouse children whom he tried to teach brick-throwing at an early age. There were weeping willows that filled a lake with their tears, where a melon grew, which, in turn, led to crying fits. Ignatz invited a pack of weasels to his home for a party, who literally made “pop” there (that is: in the club like opening champagne bottles sang “Pop-Pop-Pop” - see the song And “Pop!” Goes the Weasel , which Groucho Marx brings to our ears in the film The Marx Brothers at War ). An ostrich named Walter Kepheus Austridge put his head in a barrel that was mounted on a small cart so that he could stick his head “in the sand” while walking, and called this revolutionary invention the “little disappearance”. And so on.

language

Herriman used the Sunday pages of the strip, which, thanks to Hearst's protection, he enjoyed complete fooling freedom right to the end, not only as a playground for graphic and narrative experiments of all kinds (while his simpler Krazy Kat day trips also continued until 1944). In particular, his use of language finally broke all conventions by mixing up hit texts, slang from immigrants, twisted Spanish, French and German chunks ("Okduleeva! Vots issit?"), Surreal and absurd poetry, alliterations , phonetic spellings and secondary meanings through the consonance of different terms . The main character Krazy was simple in disposition and apparently had little of what is called education. Instead, she expressed herself in an extremely inventive and associative “hillbilly” slang, which will probably remain untranslatable forever. When Krazy z. B. (on the Sunday page of June 18, 1916) told her little niece Katrina about the earlier reign of the dinosaurs on earth, it sounded like this:

“Yes, li'l 'Ketrina', I'm a pretty smart 'Ket' - lisken, once a long time a-go there was living on this 'woil' enimals big like a house - there was 'dinny-sorrises' , 'neega-nodons', 'mega-phoniums', 'memmoths', - and great big 'lizzies'; uh, I mean 'lizzids' what was called 'itch-thyosorrises' because they were great scratchers of gardens and things, then they was big kanary birds what was called 'peter-decktils', but a-las 'Ketrina' all they is left of them now a days is their 'bones' - just 'bones' - aint that awfil? "

meaning

From a commercial point of view, Herriman's Strip was not one of the most successful works in comic history, and uncomprehending local editors of Hearst's newspapers scattered across the USA tried to prevent the strip from being printed more and more often, the more idiosyncratic, personal and supposedly incomprehensible it became over time , as complaints were received from advertisers and some readers ( Lit .: Blackbeard, 1992). Only repeated instructions from Hearst to the editors ensured that the Coconino adventures were to be found in at least one US newspaper by 1944. Although the strip eventually pissed off many readers who were looking for simpler entertainment and the vast majority of editors, a hard core of even bigger Krazy Kat followers gradually formed, who just appreciated the surreal and absurd qualities of the strip. Among them were the then US President Woodrow Wilson , the writers F. Scott Fitzgerald , Gertrude Stein and EE Cummings , the film comedians WC Fields and Charlie Chaplin and the painter Pablo Picasso . The countless narrative variations with which Herriman found new facets of his basic theme "Cat loves mouse and likes dog - mouse despises cat and hates dog - dog loves cat and pursues mouse" surprised this small but loyal readership week after week. Intellectuals and critics, above all Gilbert Seldes , praised the strip because it left plenty of room for interpretation - the poet EE Cummings represented e.g. B. the opinion that Krazy Kat is a parable for the relationship between society (Offissa Pupp), the individual (Ignatz) and the ideal (Krazy Kat) ( Lit .: Cummings, p. 16). In the end, Herriman had created around 1,500 Sunday pages and over 8,000 daily trips for the Krazy Kat cosmos without ever making any concessions in terms of content or aesthetics . From 1916 to 1935, both day and Sunday trips - apart from sporadic color experiments - appeared in black and white; from 1935 to 1944, the strip's Sunday page appeared in color.

Krazy Kat was the first surrealist work of the then still very young comic book world and at the same time a series that, even before the 1920s, went further in style and content than most of what would later follow in the medium. Talking and thus anthropomorphic animals, which today are an integral part of the comic genre of funnies , were a novelty at the time and at most known from fables , as were the simple, sketchy, direct and sometimes almost abstract drawings, which were already reminiscent of the underground style of the 1960s and 1970s. The innovative page layout, the peculiar content and the constantly changing narrative style of Krazy Kat remain unique to this day. Logically, after Herriman's death, the strip could not be continued by another illustrator - as is otherwise quite common in the comic medium.

The unusual relationship between the main characters formed the basis for all later " David- versus- Goliath " comics in the style of Tom and Jerry or Sylvester and Tweety , and the uncompromising, consistency and persistence with which an artist has been one for decades had put the extremely personal, esoteric world on paper, was recognized and admired by many later comic artists .

All Krazy Kat original comic strips have been available in hardcover book form since 2019, in German, English or French. All episodes are printed in original size and color from scans of original newspaper pages.

literature

- Bill Blackbeard: The Evolution of a Cat . In: Krazy Kat Volume 1: 1916 . Vienna 1991, ISBN 3-900390-49-5

- Bill Blackbeard: The Cat in Nine Sacks. A twenty year search for a phantom . In: Krazy Kat Volume 2: 1917 . Vienna 1992, ISBN 3-900390-54-1 .

- EE Cummings : Introduction . In: George Herriman's "Krazy Kat" - A classic from the golden age of comics . Darmstadt 1974, pp. 10-16, ISBN 3-7874-0102-4 .

- Daniela Kaufmann: The intellectual joke in comics. George Herrimans Krazy Cat . Universitäts-Verlag / Leykam, Graz 2008, ISBN 978-3-7011-0127-6 . (At the same time diploma thesis at the University of Graz 2006 under the title: The intellectual joke in comics using the example of George Herriman's "Krazy Kat" ).

- Alexander Braun: “Krazy Kat. George Herriman. The complete Sunday pages in color 1935–1944 “, Taschen , Cologne 2019, 632 pages, ISBN 978-3-8365-7194-4 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Robert C. Harvey, Brian Walker, Richard V. West: Children of the yellow kid: the evolution of the American comic strip . University of Washington Press 1998. ISBN 9780295977782 (Page 30)

- ↑ Unrequited love, a brick comes flying: George Herriman's classic comic Krazy Kat , taschen.com, accessed August 23, 2019

- ↑ George Herriman's comic "Krazy Kat": Neurotic cat meets aggressive mouse , deutschlandfunkkultur.de from August 22, 2019, accessed August 23, 2019