Marianne von Willemer

Marianne von Willemer (born November 20, 1784 in Linz (?); † December 6, 1860 in Frankfurt am Main ; probably born as Marianne Pirngruber ; also: Maria Anna Katharina Theresia Jung ) was an actress, singer ( soprano ) from Austria and dancer. At the age of 14 she moved to Frankfurt am Main, where she became the third wife of the Frankfurt banker Johann Jakob von Willemer . Linked to this friendship, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe also met Marianne in 1814 and 1815 and immortalized her in the book Suleika of his late work West-Eastern Divan . Among Goethe's numerous muses , Marianne was the only co-author of one of his works, because the “Divan” also contains - as was only known posthumously - some poems from her pen.

Origin and childhood

Marianne was the daughter of the actress Elisabeth Pirngruber. She was one of twelve children of the estate manager Johann Michael Pirngruber and grew up in Upper Austria. At the age of 23, she gave birth to an illegitimate child. There are different assumptions about the biological father and the birthplace of Marianne, which have not yet been proven. According to her own statements, she was born on November 20, 1784 in Linz and was baptized under the name Maria Anna Katharina Theresia; a corresponding entry in Linz baptismal registers has not yet been found.

On the other hand, her mother's marriage document was found in the marriage register of St. Pölten Cathedral . Not an instrument maker named Matthias Jung, whom Marianne claimed to be her father, but the theater director Joseph M. Georg Jung and Elisabeth Pirngruber were married on March 31, 1788. From then on, the then four-year-old was given the name Marianne Jung, probably to cover up the illegitimate birth.

In order to earn a living, the mother Elisabeth Pirngruber moved to Vienna, where she appeared on suburban stages. Four of her siblings living in Vienna looked after little Marianne. She grew into a lively and adaptive child and received private tuition from a pastor. Marianne also took acting and ballet lessons at an early age and was already on stage at the age of eight, a year later she was on a program at a Bratislava theater.

Relocation to Frankfurt

When the mother, whose husband had died in Pressburg in 1796, no longer received any engagements in Vienna, she and her daughter followed a couple of dancers who were friends, named Traub, to Frankfurt am Main in 1798. The income of the now 38-year-old and her daughter must have been low, so that Elisabeth Jung was doing handicrafts on the side to secure her livelihood. She saw the prospect of an engagement in distant Frankfurt as an opportunity to put an end to her plight.

But the mother only got one job as a theater servant. Marianne herself, however, was on the Frankfurt theater bill for the first time on December 26, 1798. The fourteen-year-old took on roles in operas (Der Spiegelritter) , Singspiele (Der kleine Sailor) and ballet performances (The robbed bride) . Her early appearances caused quite a stir, and she was soon featured in theater reviews. The drama industry wrote in May 1799:

- "Demoiselle Jung must have had a good teacher and does not disgrace her teacher either."

When she celebrated a great success in the ballet “Harlequin from the Egg” in the spring of 1800 , among the audience sat next to Catharina Elisabeth Goethe , the poet's mother, Clemens Brentano , who, according to his own account, fell in love spontaneously with the young actress. He wrote to her thirty years later:

- "The harlequin in the egg, / whom I once knew / until it broke in two, / he is not related at all / to this demoiselle ... / no, what I felt hand in hand / with you, dear heart, / understood not on the edge! "

The relationship with Johann Jakob Willemer

Another admirer was Johann Jakob Willemer (born March 29, 1760; † October 1838), a Frankfurt banker who had just been elected to the senior management of the theater. He came from a simple background, had worked his way up to the Privy Council at the age of 29 and, at the age of 33, his patent for the “Royal Preuss. Hofbanquier ” received. He wrote to Goethe on December 11, 1808 about his origins and his arduous ascent:

- “I grew up without an education and learned nothing. Boring poor and therefore looked over the shoulder by everyone in the Franckfurt manner and that cuts deep furrows in a tender mind, awakens life's torment, I have to earn everything I own for myself, and beyond that the most beautiful part of my life passed, and I couldn't deal with anything but making money, striving for nothing but sham honor. "

The fact that Willemer grew up poor and without education is not true. His father, Johann Ludwig Willemer, ran the Franck & Co. bank until his untimely death. Business declined as a result, but his mother continued to manage the company until the young Johann Jakob Willemer could take over. Not least because of the dowry of his first wife Meline, who came from a wealthy Berlin merchant house, he was already a wealthy man as a 24-year-old. He could afford to lease a country estate on the banks of the Main, the Gerbermühle . In addition, after selling his parents' house at Töngesgasse 49, he bought the house “Zum Roten Männchen” at the Fahrtor .

Willemer was a widower twice. His first marriage to Magdalena Lange, called Meline, had four daughters, Rosette, Käthe, Meline and Maximiliane. After the sudden death of his wife in 1792, nine months later he married Jeannette Mariane Chiron, who was seventeen years his junior. The second marriage lasted only three years; Jeannette died in childbed at the age of only 20. From this connection came the son Abraham, called Brami.

Willemer felt called to be a writer and wrote not only educational and moral works, but also five dramas, but was always dissatisfied with his own work. The theater lover Willemer had been watching Marianne Jung for a long time. He persuaded Marianne's mother to leave him the daughter for a sum of 2,000 guilders and a pension as a foster daughter. In return he promised to take care of Marianne's upbringing and musical training. Elisabeth Jung accepted this offer and traveled back to Linz. At first glance, it seems unusual for a mother to leave her 16-year-old daughter with strangers; This step becomes understandable if one considers the situation of theater actresses at this time; Elisabeth Jung knew them from personal experience: they were at the mercy of the theater owners and were only given roles up to a certain age, their social and societal position was low. To the penniless Elisabeth Jung, Willemer's offer seemed to be an opportunity to at least provide for her daughter's future.

On April 25, 1800 Marianne was on stage for the last time. She was taken in as a foster daughter in Willemer's house in Frankfurt and brought up next to his son Brami and his daughters. Over the years, Brami developed a deep bond with Marianne. Her temperament was good for him and the whole family. The house was burdened too much by the deaths of the wives and some children in recent years. There was much speculation about the relationship with old Willemer in the first few years. It was even assumed that just two years after being taken into the house, the 18-year-old and the 42-year-old became a couple. The above-mentioned letter to Goethe of December 11, 1808 shows a different picture of the relationship. He wrote:

- “The future has been gambled away with a foolish hope - of which eight years of experience have taught me that it will never come true. So I withdraw more into myself every day, become more serious and quieter. "

Marianne didn't love him. Although he had obviously promised himself more affection, he was not dissuaded from promoting Marianne further. Marianne received guitar lessons from Clemens Brentano and the guitarist Christian Gottlieb Scheidler , training in piano and singing as well as drawing lessons . She also learned Latin, Italian and French. Willemer, however, did nothing for a further acting career, and Marianne would never return to this profession. Marianne saw her mother at least three times: in 1803 and 1812 she traveled to her hometown, and in 1824 Elisabeth Jung visited her in Frankfurt.

First encounters with Goethe

Johann Jakob Willemer first met Goethe as a seventeen-year-old bank apprentice and visited him again four years later with his wife Melina. Willemer, who had not found recognition for his own literary works, saw Goethe as his idol and kept in touch with him through letters.

In the summer of 1814, Goethe returned to the Main for the first time in 17 years. He had last visited his mother in 1797; he did not come to the French-occupied city of Frankfurt for her funeral in 1808. Only after Napoléon's troops had been defeated in the Battle of the Nations near Leipzig , a visit to his hometown was considered again. Goethe wanted to visit friends there and take a cure in Wiesbaden . The invitation to him and Christiane - Goethe left on July 25, 1814 without his wife - went back to Sulpiz Boisserée : Do you seriously want to visit the Rhine ... Do it for your own sake and for my sake! .

Shortly before his departure, the publisher Johann Friedrich Cotta had sent him a collection of Persian poetry, which he had brought out in a German translation with the title “Der Diwan des Mohammed Schemseddin Hafis” . This compilation of Ghaselen ( diwan Persian ديوان= Collection) of the poet Hafiz , who had lived 500 years before him, immediately cast a spell over him. He mentions the work in his diary for the first time on June 7th, 1814, a fortnight later he wrote the first poem of the later “Divan” - “Creation and Animate” - and on July 25th, 1814 he wrote as if he anticipated what was to come :

- "So you should, lively old man, / not grieve yourself / Your hair will be white right away / But you will love."

When Willemer learned that Goethe was in Wiesbaden, he took the opportunity to visit him there on August 4th. He introduced him to his companion Marianne and invited him to visit the tanner's mill . In his diary entry from the same day, Goethe mentions the meeting in minutes:

- "4. August 1814 Wiesbaden. Go Council Willemer. Dlle. Young. Bathed. G. Council Willemer. At the Table d'Hote. "

A few days later he reported in a letter to his wife Christiane that Willemer had visited him with his "little companion". He was more impressed after he had accepted the invitation and visited the couple on August 12 at the Gerbermühle; he then noted:

- “Moonlight and sunsets; the one on Willemer's mill ... infinitely beautiful ”.

The meeting took place at a time when the almost 30-year-old Marianne had been living with Willemer for twelve years in the Willemer house. The danger of wild speculation in Frankfurt society was great. Goethe himself knew such a constellation from his own experience with Christiane Vulpius. It has not been proven, but it is very likely, that Goethe advised his friend Willemer to legitimize the relationship legally, since the wedding took place at short notice - on September 27, 1814 - and without a call. Pastor Anton Kirchner married the couple in the house with the Red Man (at the Fahrtor).

On the occasion of another visit on October 12th, Goethe noted:

- “Evening to Mrs. Privy Councilor Willemer: for this our worthy friend is now married in forma. She is as kind and good as ever. He wasn't at home ”.

On October 18, 1814, the Willemer couple met with Goethe in the Willemer-Häuschen , a summer house on the Mühlberg, acquired in 1809, to observe the bonfires on the occasion of the first anniversary of the Battle of Leipzig. Goethe wrote in a letter about the incident in 1815:

"[...] Then I visualized the friends and the little flames so delicately dotted over Frankfurt's panorama, all the more so when it was just a full moon, in front of whose face lovers should always feel strengthened in an invincible affection."

On October 20, Goethe left for Weimar. Regular correspondence between him and Marianne began over the next few months.

Summer at the Gerbermühle and in Heidelberg (1815)

In a letter dated April 10, 1815, Jakob Johann Willemer invited Goethe to take another trip home:

- “You will soon recover from the complaints of the winter in Weimar on the banks of the Main. You could initiate the pre-treatment for Oberrad and live with us on the mill. There is enough space, and my wife and I would never have felt more joy than to see you as our guests. When you are tired of the sun and of work, she sings your songs to you. "

Willemer alluded to the illness of Goethe's wife Christiane, who had suffered a stroke at the beginning of the year.

On May 24, 1815, Goethe traveled - again alone - from Weimar to the Rhine-Main area, where he stayed mostly in Wiesbaden until July 21, 1815. He wanted to end his trip with a visit to the Willemers on August 12th at their country estate. He stayed longer than planned: he stayed at the Gerbermühle until September 17th , apart from a temporary stay in Willemer's townhouse from September 8th to 15th. In addition to the Willemers and Goethe, the young architect Sulpiz Boisserée was also a guest at the Gerbermühle these days. In the mornings, Goethe mainly worked on the West-Eastern Divan , which he had started the previous year and which was to be published for the first time in 1819. At lunchtime they dined together and in the afternoon strolled through the rural surroundings. In the evening Goethe recited the verses he wrote during the day, and Marianne not only sang his songs, but increasingly entered into a lyrical dialogue with him.

In this cheerful atmosphere, not only did Goethe's new work quickly grow in volume, German literature also owes it some of Goethe's love poems. Shortly before the end of his visit, Goethe's affection was also expressed in writing for the first time. In his first hatem song, he confessed:

- Opportunity does not make thieves

- She is the greatest thief herself

- Because she stole the rest of the love

- That still stayed in my heart.

Marianne replied a few days later by taking up his words and paraphrasing:

- Delighted in your love

- I do not scold opportunity

- Was she a thief on you too?

- How such a robbery delights me.

On September 18, Goethe traveled on to Heidelberg. The Willemer couple surprised him with a visit there on September 23. Marianne had brought her friend a poem that was to be included in the divan as a song from the east wind :

- What does the movement mean?

- Does the East bring me good news?

- Fresh impetus in his wings

- Cools the heart's deep wound.

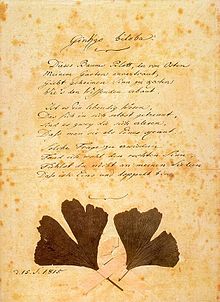

In these lines the imminent farewell to Goethe is indicated, and Marianne probably suspected that they would not see each other again anytime soon. In those days when you went for walks - “First over the bridge then to the Carlsthor. The Neckar upward. "As Goethe wrote - created more Divan -Poems, including Goethe's ode recovery , with the verses" Is it possible. Star of the Stars / I will press you to my heart again ”begins. September 27, 1815 was the last day on which the two met, after which they never saw each other.

From the ensuing correspondence, which was to last until Goethe's death, Goethe included the following verses by Marianne in the divan :

- Sweet poetry, pure truth

- Captivate me in sympathy!

- Pure embodies clarity of love

- In the guise of poetry.

He answers her later, also in the "Divan":

- You woke me up with this book, you gave it;

- Because what I said gladly, with all my heart,

- That sounded back from your lovely life

- Like look after look, so rhyme after rhyme.

For Goethe it was the only time in his life and work that a woman became a co-creator of his poetry. Marianne von Willemer was not only the model of Suleika , Goethe also incorporated three of her poems into his work:

- Delighted in your love (title in the book Suleika: Suleika )

- What does the movement mean (east wind)

- Oh, about your damp wings (title in the book Suleika: West Wind )

On October 21, 1815, meanwhile returned to Weimar, he reported to a friend in a letter that he could "report with pleasure that new and rich sources have opened up for the Divan, so that it has been expanded in a very brilliant way." Both Both Goethe and Marianne were silent about the true authorship of Marianne's part. Even in his memoirs, Poetry and Truth , he did not reveal the circumstances under which large parts of the divan had come into being. They only became known posthumously through the Germanist Herman Grimm ( Wilhelm Grimm's son ), whom Marianne confided in shortly before her death.

Once again, in June 1816, shortly after the death of his wife Christiane, Goethe set off on a trip to the Rhine, but had to break off the trip after only two hours because of a broken wheel in his car.

After 1832: years of parting

Goethe died on March 22nd, 1832. After the news had been brought to her, Marianne said: “God gave me this friendship. He took it from me. I have to thank God that it was part of me for so long. ”How much Goethe meant to her and also what she had meant to him, Marianne kept to herself until her death.

Together with Willemer, she made a few trips to Italy. Her husband suffered a stroke in 1836 at the age of 77. Marianne cared for him in the last two years of his life until his death in 1838. On October 22nd, 1838 Johann Jakob Willemer was buried next to his first wife at the church in Frankfurt-Oberrad . Marianne von Willemer outlived her husband by 22 years.

After spending 38 years at Willemer's side, Marianne felt lonely after his death. The marriage had remained childless, and a year after her husband's death she wrote:

- “I am not an independent being, but my poor, dearly loved and deeply weeping patient was my only support, everything in my life was calculated on him; that was suddenly over ”.

She moved into an apartment at Alte Mainzer Gasse 42 and gave piano and singing lessons. Having become silent, she nonetheless maintained contact with artists and supported them; For example, she made sure that the art collection of the brothers Melchior and Sulpiz Boisserée was sold to the Bavarian king for 240,000 guilders. This forms the basis of the Alte Pinakothek in Munich.

Marianne von Willemer died of a heart attack on December 6, 1860 at the age of 76 and was buried in the grave of the Andreae family in the Frankfurt main cemetery.

reception

Marianne von Willemer was the only one of Goethe's numerous muses who can be called a co-author of one of his works. She never published under her own name, but her poems, which were incorporated into the West-Eastern Divan , attracted attention during her lifetime, when her authorship was still unknown. Franz Schubert , who set numerous poems by Goethe to music, composed in March 1821 What does the movement mean ( Suleika I , D.720, Opus 14) and in 1828 Oh, about your damp wings ( Suleika II , D.717, Opus 31).

In memory of Marianne von Willemer, the City of Linz Women's Office initiated the Marianne von Willemer Prize .

A primary school was named after her in the Sachsenhausen district of Frankfurt.

literature

- Constantin von Wurzbach : Willemer, Marianne von . In: Biographisches Lexikon des Kaiserthums Oesterreich . 56th part. Kaiserlich-Königliche Hof- und Staatsdruckerei, Vienna 1888, pp. 182–187 ( digitized version ).

- Klaus-Werner Haupt: Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and the Persian Diwan des Hafis. In: OKZIDENT & ORIENT. The fascination of the Orient in the long 19th century. Weimarer Verlagsgesellschaft / Imprint of the publishing house Römerweg Wiesbaden 2015, ISBN 978-3-7374-0220-0 , pp. 31–43.

- Kurt Andreae (ed.): The family book of Marianne von Willemer. Frankfurt / Leipzig 2006, ISBN 978-3-458-17323-6 .

- Sigrid Damm : Christiane and Goethe. A research . Frankfurt am Main 2001, ISBN 3-458-34500-0 , p. 455 ff.

- Walter Laufenberg : Goethe and the Bajadere. The secret of the west-east divan. Munich 1993, ISBN 3-7766-1802-7 .

- Gustav Gugitz : Marianne Willemer: corrections to her life story and her relationship to Linz. In: Upper Austrian homeland sheets. Issue 3/1959, pp. 279–284, online (PDF) in the forum OoeGeschichte.at.

- Wolfgang-Hagen Hein, Dietrich Andernacht: The garden of the pharmacist Peter Saltzwedel and Goethe's Ginkgo biloba. In: Annaliese Ohm, Horst Reber (ed.): Festschrift for Peter Wilhelm Meister on his 65th birthday on May 16, 1974. Hamburg 1975, pp. 303-311.

- Hermann A. Korff (Ed.): The love poems of the west-east Divans. Stuttgart 1947, OCLC 485980222 .

- Siegfried Unseld : Goethe and the Ginkgo. A tree and a poem. Frankfurt am Main 1998, ISBN 3-458-19188-7 .

- Hans-Joachim Weitz (Ed.): Correspondence with Marianne and Johann Jakob Willemer / Johann Wolfgang Goethe . Frankfurt am Main 1986, ISBN 3-458-32600-6 .

- Kutsch / Riemens: Large song dictionary . 3 volumes. Unchanged edition. KG Saur, Bern 1993, third volume supplementary volume, ISBN 3-907820-70-3 , p. 1087.

- Ruth Istock: Since your name is Suleika now . Marianne von Willemer's Goethe Years. Gollenstein, Blieskastel 1999, ISBN 3-930008-97-1 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Marianne von Willemer in the catalog of the German National Library

- Goethe: West-Eastern Divan in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Lexicon article "Willemer, Marianne" by the Sophie Drinker Institute

- Entry on Marianne von Willemer by Daniel Ehrmann for the Upper Austrian literary history of the StifterHaus

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Reinhold Dessl: Johann Michael Pirngruber (1716–1800). A Gramastettner as the grandfather of Goethe's Suleika. In: Upper Austrian homeland sheets . Linz 2013, pp. 54–58, PDF on land-oberoesterreich.gv.at.

- ↑ a b c d e Dagmar von Gersdorff, Marianne von Willemer and Goethe - story of a love. Frankfurt am Main 2003, ISBN 3-458-17176-2 , pages 29,39,40ff, 185.

- ↑ Gugitz 1959, p. 279.

- ↑ a b Konstanze Crüwell: Willemer house in new splendor. In: FAZ-Online. May 29, 2006, accessed February 2, 2020 .

- ^ Björn Wissenbach: Willemerhäuschen. In: Hiking trail around Sachsenhausen. No. 3, p. 11.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Willemer, Marianne von |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Jung, Marianne (maiden name); Pirngruber, Marianne |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Friend of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe |

| DATE OF BIRTH | November 20, 1784 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | uncertain: Linz |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 6, 1860 |

| Place of death | Frankfurt am Main |